Alvin Cullum York was one of the most decorated United States Army soldiers of World War I. He received the Medal of Honor for leading an attack on a German machine gun nests, killing at least 25 enemy soldiers, and capturing 132 during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. He was also a conscientious objector.

Biography of Alvin Callum York

York was born on December 13, 1887 to William and Mary York of Pall Mall, Tennessee and raised in a two-room log cabin in a rural backwater in the northern section of Fentress County. He was the third oldest of a family of eleven children. Like many families in the county, the York family eked out a hardscrabble existence of subsistence farming supplemented by hunting. York’s father, also acted as a part time blacksmith to provide some extra income for the family.

In the wake of his father’s death in 1911, York, as the eldest still living in the area, was forced to aid his mother in raising his younger siblings. To support the family, he began working in railroad constructions and as a logger in Harriman, Tennessee.

Alvin Callum York Earned a Reputation as a Deadly Accurate Marksman

As York came of age he earned a reputation as a deadly accurate marksman and a hell raiser. Drinking and gambling in borderline bars, York was generally considered a nuisance and someone who “would never amount to anything.” That reputation underwent a serious overhaul when York experienced a religious conversion in 1914. In that year two significant events occurred: his best friend, Everett Delk, was beaten to death in a bar fight in Static, Kentucky; and he attended a revival conducted by H.H. Russell of the Church of Christ in Christian Union. Delk’s senseless death convinced York that he needed to change his ways or suffer a fate similar to his fallen comrade, which prompted him to attend prayer meetings.

A strict fundamentalist sect with a following limited to three states – Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee – the Church of Christ in Christian Union embraced a strict moral code which forbade drinking, dancing, movies, swimming, swearing, popular literature, and moral injunctions against violence and war. Though raised Methodist, York joined the Church of Christ in Christian Union and in the process convinced one of his best friends, Rosier Pile, to join as well. Blessed with a melodious singing voice, York became the song leader and a Sunday school teacher at the local church. Rosier Pile went on to become the church’s pastor. The church also brought York in contact with the girl who would become his wife, Gracie Williams.

By most accounts, York’s conversion was sincere and complete. He quit drinking, gambling, and fighting. When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, York’s new found faith would be tested. He received his draft notice from his friend, the postmaster and pastor, Rosier Pile, on June 5, 1917, just six months prior to his thirtieth birthday. Because of the Church of Christ in Christian Union’s proscriptions against war, Pile encouraged York to seek conscientious objector status. York wrote on his draft card: “Don’t want to fight.” When his case came up for review it was denied at both the local and the state level because the Church of Christ in Christian Union was not recognized as a legitimate Christian sect.

York was assigned to Company G, 328th Infantry Regiment 82nd Infantry Division known as “The All American Division” and posted to Camp Gordon in Georgia. The 82nd lives today as the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division.

York proved his skill as a crack shot but was seen as an oddity because he did not wish to fight. This led him to have extensive conversations with his company commander, Capt. Edward C.B. Danforth, and his battalion commander, Maj. G. Edward Buxton, relating to the Biblical justification for war. A devout Christian, Buxton cited a variety of Biblical sources to counter his subordinate’s concerns.

Challenging York’s pacifist stance, the two officers were able to convince the reluctant soldier that war could be justified. Following a ten-day leave to visit home, York returned with a firm belief that God meant for him to fight.

Traveling to Boston, York’s unit sailed for Le Havre, France in May 1918 and arrived later that month after a stop in Britain. Reaching the Continent, York’s division spent time along the Somme as well as at Toul, Lagney, and Marbache where it underwent a variety of training to prepare it for combat operations along the Western Front. Promoted to corporal, York took part in the St. Mihiel offensive that September as the 82nd sought to protect the U.S First Army’s right flank. With the successful conclusion of fighting in that sector, the 82nd was shifted north to take part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, a battle that cost 28,000 German lives and 26,277 American lives, making it the largest and bloodiest operation of World War I for the American Expeditionary Force (AEF).

Entering the fighting on October 7 as it relieved units of the 28th Infantry Division, York’s unit received orders that night to advance the next morning to take Hill 223 and press on to sever the Decauville Railroad north of Chatel-Chehery. Advancing around 6 am the next morning, the Americans succeeded in taking the hill.

Moving forward from the hill, York’s unit was forced to attack through a triangular valley and quickly came under German machine gun fire on several sides from the adjacent hills. This stalled the attack as the Americans began taking heavy casualties. In an effort to eliminate the machine guns, 17 men led by Sgt. Bernard Early, including York, were ordered to work around into the German rear. Taking advantage of the brush and hilly nature of the terrain, these troops succeeded in slipping behind the German lines and advanced up one of the hills opposite the American advance.

In doing so, they overran and captured a German headquarters area and secured a large number of prisoners including a major. While Early’s men began securing the prisoners, the German machine gunners up the slope turned several of their guns and opened fire on the Americans. This killed six and wounded three, including Sgt. Early, leaving York in command of the remaining seven men. With his men behind cover guarding the prisoners, York moved to deal with the machine guns. Beginning in a prone position, he utilized the shooting skills he had honed as a boy.

Alvin Callum York was Awarded the Distinguished Service Cross

Picking off the German gunners, York was able to move to a standing position as he evaded enemy fire. During the course of the fight, six German soldiers emerged from their trenches and charged at York with bayonets. Running low on rifle ammunition, he drew his pistol and dropped all six before they reached him. Switching back to his rifle, he returned to sniping at the German machine guns. Believing he had killed around 20 Germans, and not wishing to kill more than necessary, he began calling for them to them to surrender.

This resulted in German First Lieutenant Paul Jurgen Vollmer – a highly decorated officer who had recently assumed command of the 120th Wurttemberg Landwehr Regiment’s 1st Battalion – emptying his pistol trying to kill York while he was contending with the machine guns. Failing to injure York, and seeing his mounting losses, he offered in English to surrender the unit to York, who accepted. Rounding up the prisoners in the immediate area, York and his men had captured around 100 Germans. With Vollmer’s assistance, York began moving the men back towards the American lines. In the process, another thirty Germans were captured. Advancing through artillery fire, York succeeded in delivering 132 prisoners to his battalion headquarters. This done, he and his men rejoined their unit and fought through to the Decauville Railroad. In the course of the fight, 28 Germans were killed and 35 machine guns captured. York’s actions clearing the machine guns reinvigorated the 328th’s assault and the regiment advanced to secure a position on the Decauville Railroad.

Upon returning to his unit, York reported to his Brigade Commander, Gen. Julian R. Lindsey, who remarked “Well York, I hear you have captured the whole damn German army.” York replied “No sir. I got only 132.”

For his achievements, York was promoted to sergeant and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Remaining with his unit for the final weeks of the war, his decoration was upgraded to the Medal of Honor which he received on April 18, 1919. The award was presented to York by American Expeditionary Forces commander. In addition to the Medal of Honor, York received the French Croix de Guerre and Legion of Honor, as well as the Italian Croce al Merito di Guerra. When given his French decorations by Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the supreme allied commander commented, “What you did was the greatest thing ever accomplished by any soldier by any of the armies of Europe.” Arriving back in the United States in late May, York was hailed as a hero and received a ticker tape parade in New York City.

That York deserves credit for his heroism is without question. Unfortunately, however, his exploit has been blown out of proportion with some accounts claiming that he silenced thirty-five machine guns and captured 132 prisoners single-handedly. York never claimed that he acted alone, nor was he proud of what he did. Twenty-five Germans lay dead, and by his accounting, York was responsible for at least nine of the deaths. Only two of the seven survivors were acknowledged for their participation in the event; Sgt. Early and Cpl. Cutting were finally awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in 1927.

York’s life caught fire in the American imagination not because of who he was, but what he symbolized: a humble, self-reliant, God-fearing, taciturn patriot who slowly moved to action only when sufficiently provoked and then adamantly refused to capitalize on his fame. George Pattullo, the Saturday Evening Post reporter who broke the story, focused on the religion-patriotic nature of York’s feat. He titled his piece “The Second Elder Gives Battle,” referring to York’s status in his home congregation in Pall Mall, Tennessee.

York turned his back on quick and certain fortune in 1919, and went home to Tennessee to resume peacetime life and married the love of his life, Gracie Williams. Over the next several years, the couple had seven children.

Alvin Callum York Sought to Improve Educational Opportunities for Children

Largely unknown to most Americans was the fact that Alvin York returned to America with a single vision: he wanted to provide a practical educational opportunity for the mountain boys and girls of Tennessee. Understanding that to prosper in the modern world an education was necessary, York sought to bring Fentress County into the twentieth century. Thousands of like-minded veterans returned from France with similar sentiments and as a result college enrollments shot up immediately after the war.

A celebrity, York took part in several speaking tours and eagerly sought to improve educational opportunities for area children. This culminated with the opening of the Alvin C. York Agricultural Institute in 1926. Though he possessed some political ambitions, these largely proved fruitless. Throughout the 1920s York went on speaking tours to endorse his hopes for education and raise money for York Institute. He also became interested in state and national politics. A Democrat in a staunchly Republican county, York’s endorsement carried a degree of clout for pols. York also used his celebrity to improve roads, employment, and education in his home county.

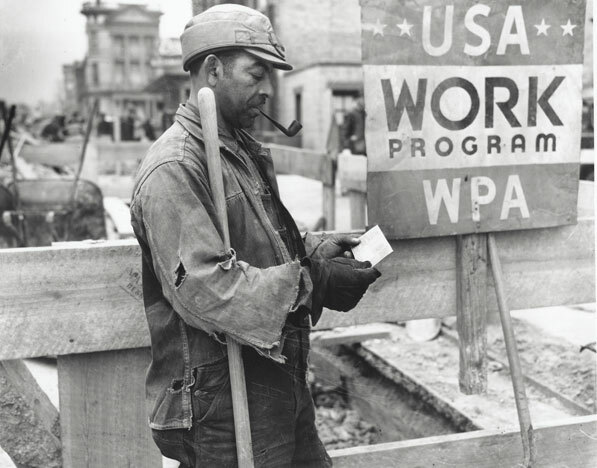

York withdrew from the national spotlight during the 1930s, and focused his waning political aspirations on the state rather than the local level. He considered running for the U.S. Senate against the freshman senator, Albert Gore (father of Vice President Al Gore). In the 1932 election, he changed his party affiliation and supported Herbert Hoover over Franklin D. Roosevelt because FDR promised to repeal Prohibition. Once the New Deal got underway, however, York returned to the Democratic Party and endorsed the president’s public work relief programs, especially the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

In 1939, York was appointed superintendent of the Cumberland Homesteads near Crossville. The community was envisioned by federal planners as a model of cooperative living for the region’s distressed farmers, coal miners, and factory workers. While the cooperative experiment failed and the federal government withdrew from the project in the 1940s, the Homesteads community nevertheless survived.

In 1935 York delivered a sermon entitled, Christian Cure for Strife, which argued that the vigilant Christian should ignore current world events, because Europe stood poised on the brink of another war and Americans should avoid it at all costs. Recalling his career as a soldier, York renounced America’s involvement in World War I. He said, “In order to achieve world peace, Americans must first secure it at home beginning with their own families. The church and the home, therefore, represented the cornerstones of world peace.”

At the same time, the threat of war had rekindled the interest of some filmmakers, most notably Jesse L. Lasky, into reviving the story of York’s exploits during World War I. Lasky, having witnessed the famous New York reception of the hero from his eighth floor office window in May of 1919 had wanted then to tell York’s story.

Because the Church of Christ in Christian Union condemned movies as sinful, Lasky had a tough time convincing York that a film based on his life was justified. York finally agreed when he decided that the money made from the film could be used to create an interdenominational Bible school.

Alvin Callum York Questioned America’s Involvement in the First World War

Through York’s association with Lasky and Warner Brothers, he became convinced that Hitler represented the personification of evil in the world and turned belligerent. York’s conversion to interventionism was so complete that he wholeheartedly agreed with Gen. George C. Marshall that the U.S. should institute its first peacetime draft. Governor Prentice Cooper approved York’s endorsement by naming him chief executive of the Fentress County Draft Board, and appointed him to the Tennessee Preparedness Committee to help prepare for wartime.

In 1937, York not only condemned war but also questioned America’s involvement in the First World War. In that same year, York joined the Emergency Peace Campaign which lobbied against any U.S. involvement in the growing tensions in Europe. A pious peaceful man, York had fought his country’s enemy only after great deliberation and had to be convinced that war was sometimes necessary. His personal struggle in World War I found new resonance in an America at odds over the recent European war, for York personified isolationist Christian America wrestling with its conscience over whether or not to engage in the current war abroad.

In 1940-41, York joined the Fight for Freedom Committee which combated the isolationist stance of America First, and York became one of its most vocal members. Up until Pearl Harbor, York battled another legendary American hero, the man who symbolized America First to the general public, Charles Lindbergh. Meantime, the film “Sergeant York” starring Gary Cooper, became one of the top grossing Warner Brothers films of the entire war era and earned Cooper the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1942.

York’s Health Began to Deteriorate After the War

During the war, York attempted to reenlist in the infantry but could not do so due to age and obesity. Instead, through an affiliation with the Signal Corps, York traveled the country on bond tours, recruitment drives, and camp inspections. Ironically, the Bible school that was built with the proceeds from the movie opened in 1942, but the very people the school was intended for had either enlisted in the armed services or moved north to work in defense related industries. The school closed in 1943 never to reopen.

York’s health began to deteriorate after the war and in 1954 he suffered from a stroke that would leave him bedridden for the remainder of his life. In 1951, the Internal Revenue Service accused York of tax evasion regarding profits earned from the movie. Unfortunately, York was practically destitute in 1951. He spent the next ten years wrangling with the IRS, which led Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn and Congressman Joe L. Evins to establish the York Relief Fund to help cancel the debt.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy ordered that the matter be resolved and considered the IRS’s actions in the case to be a national disgrace. The relief fund paid the IRS $100,000 and placed $30,000 in trust to be used in the family’s best interest.

York died on September 2, 1964 and was buried with full military honors in the Pall Mall cemetery. His funeral was attended by Governor Frank G. Clement and Gen. Matthew Ridgway as President Lyndon B. Johnson’s official representative. He was survived by seven children and his widow.

When asked how he wanted to be remembered, the old sergeant said he wanted people to remember how he tried to improve basic education in Tennessee because he considered a solid education the true key to success. It saddened him somewhat that only one of his children went on to college, but he was proud of the fact that they all had received high school diplomas from York Institute. Most people, of course, do not remember him as a proponent for public education. York’s memory is forever tied to Gary Cooper’s laconic screen portrayal of the mountain hero and the myth surrounding his military exploits in the Argonne in 1918.

Battle scene from Sergeant York starring Gary Cooper: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtk488k1-yM

0 Comments