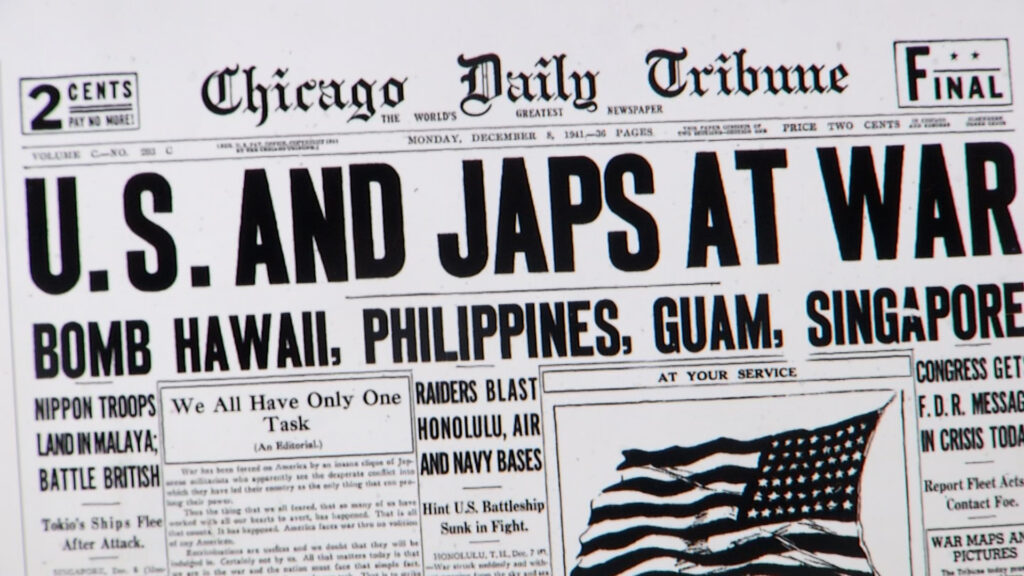

When Americans woke up Sunday morning on December 7, 1941, they were stunned to learn Japanese naval aircraft had attacked Pearl Harbor. What they would soon find out that was only the beginning. Pearl Harbor was just one part of the Japanese plan for the day. Within hours, Japanese naval and ground forces attacked and invaded Wake Island, Guam, Malaya, Singapore, Honk Kong, Thailand and Burma.

The Onset of War: The Angels of Bataan Face Their First Test

Ten hours after the devastating surprise attack that crippled the U.S. Pacific Fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor, Japanese planes launched the first in a deadly series of attacks on the Philippine Islands, bombing and strafing military airfields and bases in and around Manila. Caught in the air raids were ninety-nine army and navy women nurses. Immediately they rushed to their respective hospitals and began assisting with the endless flow of military and civilian casualties. It is almost certain that none ever dreamed they would be thrust into a deadly shooting war.

Unknown to them and others was two Japanese convoys were steaming toward Luzon with thousands of combat forces to defeat Philippine forces and their American counterparts.

The Fall of Manila: The Angels of Bataan’s Retreat to Safety

Japanese forces landed first on the southern tip of Luzon on December 11, far away from Manila to become an immediate concern. Eleven days later on December 22, over 43,000 Japanese troops of General Homma’s 14th Army landed at Luzon’s Lingayen Gulf with artillery and 100 tanks, catching the already badly war-damaged Manila in a deadly crossfire.

By Christmas, with Japanese ground forces on the outskirts of Manila, American medical personnel were ordered to retreat to the Bataan Peninsula. The Army nurses, together with Navy nurse, Ann A. Bernatitus, under the command of Capt. Maude Davison escaped within hours before Manila fell.

The navy nurses, under the command of Lt. Laura M. Cobb, stayed behind in Manila to support the patients there. She and her 11 navy nurses were soon captured and interned by the Japanese in the Santo Tomas Internment Camp on the campus of the University of Santo Tomas.

The Angels of Bataan in the Jungles of Bataan and Corregidor

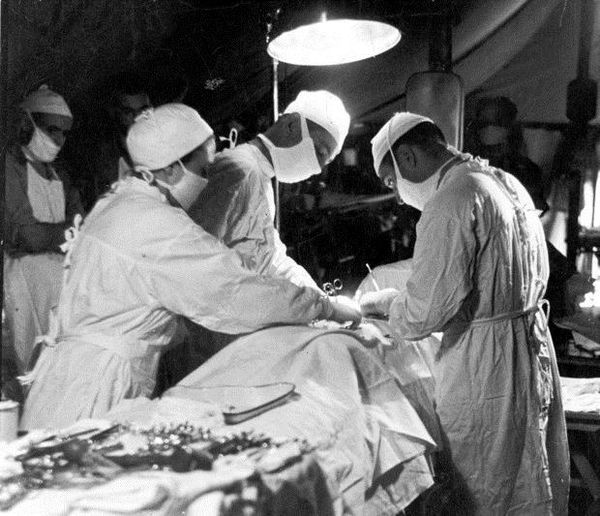

In Bataan, two field hospitals had been set up in the steamy jungle wetlands, complete with swamps, bugs, snakes, rats and mosquitoes feasting on patients and nurses, adding Malaria to an ever-growing list of problems. Within hours of arriving, casualties began pouring in. Early patients were placed in hospital beds but as more and more casualties arrived daily, others were stacked on triple-tiered bamboo bunks in overcrowded wards in open-air tents.

Soon the Japanese discovered the hospitals and started heavy aerial bombardments. Nurses dodged bombshell fragments while ministering to their patients. When explosions came close to the wards, some nurses would protect their patients from falling shrapnel by spreading their arms over them.

For four months the women worked their shifts in temperatures that reached 104 degrees. Every sort of Medicine including painkillers were running out. Rations were twice cut in half. Yet ridden with disease, starvation and in constant danger for their lives, these “Angels of Bataan” as they became known, worked from daybreak until dark giving aid to 5,000 wounded men and assisting surgeons perform operations.

With the constant bombing by Japanese planes and supplies running out completely, the nurses were ordered to retreat to Corregidor. They were also ordered to leave behind their patients. The women became angry and confused: Their job was to care for their patients, not abandon them. According to diaries and later interviews, they felt like traitors leaving behind “the boys” in their beds in the middle of a jungle wasteland. None ever got over the eyes of their patients as they left to board boats for transport to the tiny island of Corregidor. Each lived to regret it in her own way.

Two days later, on April 9, 1942, the weary, emaciated American soldiers on Bataan surrender to the Japanese. That same day, approximately 60,000-80,000 Filipino and American military prisoners of war began an 80 mile march to a POW prison at Camp O’Donnell where physical abuse, denied food and water and wholesale murder were widespread it what became known as the Bataan Death March. Some 2,500-10,000 Filipino and 100-650 American prisoners of war died before they could reach their destination.

Conditions and treatment were so bad at Camp O’Donnell, around 20,000 Filipinos and 1,600 Americans died. It was liberated by the US Army and Philippine Commonwealth Army January 30, 1945. Some of the Japanese responsible for the atrocities on the march and in the prison were hanged for war crimes.

When the nurse arrived on the six square mile island of Corregidor, they were thrust into the dank underground maze of tunnels dug deep into the bowels of the island. They joined the medical staff already working in the underground hospital and wards in the cavernous Malinta Tunnel.

On April 29, a small group of Army nurses were evacuated, with other passengers, aboard a navy PBY Catalina. On May 3, the sole Navy nurse, Ann Bernatitus, a few more Army nurses, and a small group of civilians were evacuated aboard the submarine USS Spearfish (SS-190).

Three days later, on May 6, 1942, Corregidor surrendered.

The Endurance of the Angels of Bataan

At noon a bugler played “taps” as two American officers lowered the Stars and Stripes from the flagpole outside the entrance to Malinta Tunnel. In its place, a single white sheet of surrender was raised. A small piece of the flag was cut off by one officer as a memento and then set the rest of the Red, White and Blue on fire.

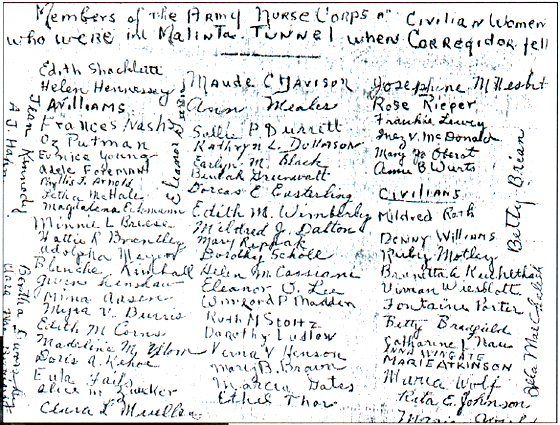

Underground the women ripped a large square of cloth from a rough muslin bed sheet and wrote at the top, “Members of the Army Nurse Corps and Civilian Women who were in Malinta Tunnel when Corregidor fell.” Underneath in three columns, the 69 women signed their names.

On July 2, 1942, the nurses were transported to the Santo Tomas Internment Camp. Capt. Davison, 57 years old and with 20 years of service experience, took command of the nurses and instructed her fellow nurse captives to put on their working uniforms and create an infirmary. The Angels of Bataan had arrived.

Resilience in Captivity: The Angels of Bataan’s Fight for Survival

Over the course of two years, the nurses ministered to captive soldiers and American civilians. To maintain morale, Davison created a structure within the ranks, requiring nurses to work at least four-hour shifts each day. She wisely understood that keeping her nurses busy caring for others would give them purpose and less time thinking about their own miseries.

In May 1943, the navy nurses, still under the command of Lt. Cobb, were transferred to a new internment camp at Los Banos, where they established an infirmary and continued working as a nursing unit and became known as “the sacred eleven.”

Photo was taken of the navy nurses shortly after they were liberated in February 1945.

In January 1944, control of the Santo Tomas Internment Camp changed from Japanese civil authorities to the Imperial Japanese Army, with whom it remained until the camp was liberated.

Access to outside food sources was curtailed, the diet of the internees was reduced to 960 calories per person per day by November 1944, and further reduced to 700 calories per person per day by January 1945.

The nurses lost, on average, 30% of their body weight during internment, and subsequently experienced a degree of service-connected disability “virtually the same as the male ex-POW’s of the Pacific Theater.” Maude Davison’s bodyweight dropped from 156 lbs. to 80 lbs.

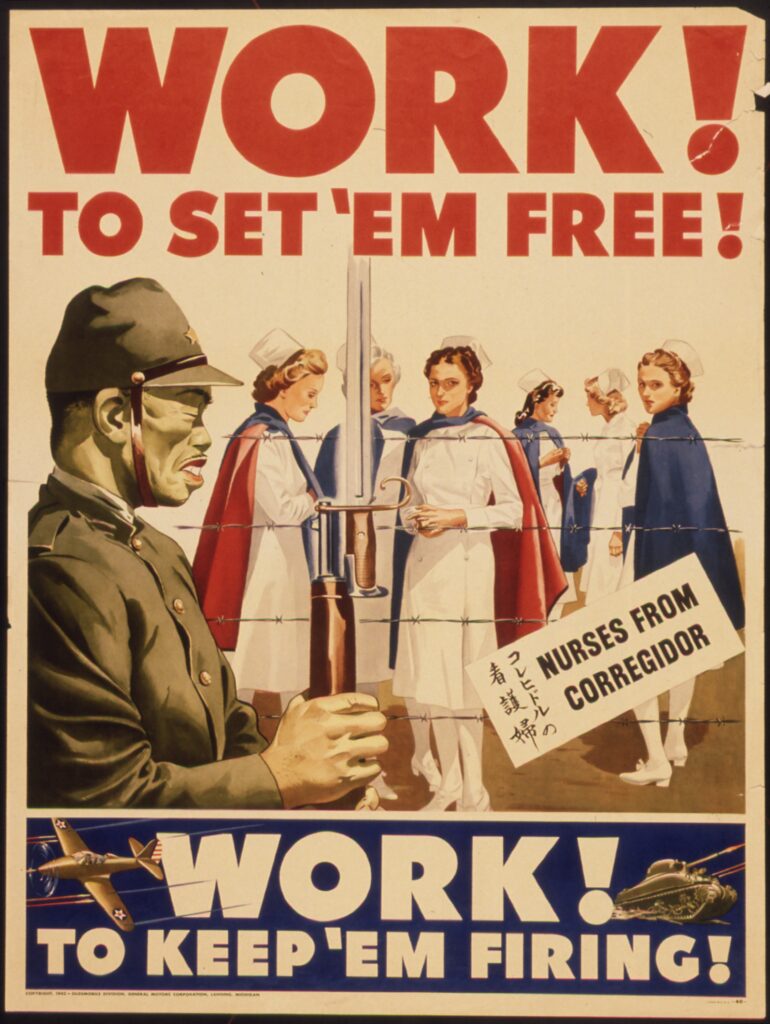

News of the captured military nurses spread throughout the U.S. While their status as POWs was known, details of their living conditions were sketchy. Using the plight of the nurses as a battle cry on the home front, federal authorities distributed posters urging American citizens to “Work! To set ’em free!”

Lt. Juanita Redmond, one of the few nurses to escape during the last few days before Corregidor surrendered, published a memoir of her experiences on Bataan in 1943 that concluded with a dramatic reminder that her colleagues were still prisoners. Her best-selling book, “I Served on Bataan,” was also the basis for the motion picture, “So Proudly We Hail.” In the theaters where the movie was shown, recruitment booths staffed with Red Cross volunteers were set up in the lobbies.

True to his promise that he would return to liberate the Filipino people, General Douglas MacArthur‘s forces retook the Philippine Islands from the Japanese. The internees at Santo Tomas, including the nurses, were liberated on February 3, 1945, by a “flying column” of the 1st Cavalry. The navy nurses were subsequently liberated in the Raid at Los Banos.

While thousands of men had died during the course of the Philippines Campaign, all 77 nurses made it out alive.

Through four years of deprivation, cruelty and constant death, they valiantly served to save others. None of the Army or Navy nurses are thought to survive today. Many died fairly young. Others had chronic gastrointestinal and dental problems, as well as emotional and post-traumatic stress symptoms.

A Bronze Plaque was Erected for the Angels of Bataan in Their Honor on April 9, 1980

The men whose lives were touched by the Angels of Bataan and Corregidor erected a bronze plaque in their honor on April 9, 1980. It is at the Mount Samat shrine on the Bataan Peninsula. It reads:

TO THE ANGELS– In honor of the valiant American military women who gave so much of themselves in the early days of World War II. They provided care and comfort to the gallant defenders of Bataan and Corregidor.

They lived on a starvation diet, shared the bombing, strafing, sniping, sickness and disease while working endless hours of heartbreaking duty. These nurses always had a smile, a tender touch and a kind word for their patients. They truly earned the name – THE ANGELS OF BATAAN AND CORREGIDOR.

Read About Other Military Myths and Legends

If you enjoyed learning about the Angels of Bataan, we invite you to read about other military myths and legends on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

I just discovered your great blog! My aunt (my father’s younger sister) was Ethel “Sally” Blaine Millett, an Army nurse who served at Bataan, was evacuated with a few other nurses, early because they had malaria. Their seaplane hit a rock landing at Mindanao to get fuel. The fuel tank was torn, the pilot fled, and “Sally” and the others tried unsuccessfully to hide from the Japanese. They were captured after only a few days and transported to Sano Tomas. I was blessed to have been given all of “Sally’s” personal papers, and I am currently writing a book about her.