Most military historians and analysts agree the 1968 Tet Offensive was the turning point in the war in Vietnam. They reason that many Americans, seeing the bitter fighting raging up and down South Vietnam on the evening news, fostered a psychological impact that further generated an increased anti-war sentiment.

Although the Tet Offensive began on January 31, 1968, when the North Vietnamese and Vietcong forces launched massive, well-coordinated surprise attacks on major cities, towns, and military bases throughout South Vietnam, it’s planning began in early 1967. The plan’s architect was General Vo Nguyen Giap, North Vietnam’s most brilliant military mind. He also engineered the Viet Minh‘s decisive victory over French forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

His overall plan for the Tet Offensive was somewhat similar: to ignite a general uprising among the South Vietnamese people, shatter the South Vietnamese military forces, and topple the Saigon regime. At the same time, he wanted to increase the level of pain for the Americans by inflicting more casualties on U.S. Forces. At the very least, he and the decision-makers in Hanoi hoped to position themselves more favorably in any peace negotiations they hoped would take place in the wake of the offensive. Much in the same way, the April 1954 Geneva Agreements forced France to abandon its colonies on the Indochinese peninsula.

The first step in Giap’s plan was to draw U.S. and Allied attention away from the population centers, which would be their ultimate objectives for the 1968 Tet Offensive. This phase began in the summer months of 1967 when NVA forces engaged the Marines in a series of sharp battles in the hills surrounding Khe Sanh, a base in western Thua Thien Province, south of the DMZ near the Laotian border. Further to the east, additional NVA forces besieged the Marine base at Con Thien just south of the Demilitarized Zone. Further south, Communist forces attacked Loc Ninh and Song Be, both in III Corps Tactical Zone, and in November, they struck U.S. forces at Dak To in the Central Highlands.

In purely tactical terms, these “border battles” were costly failures for the Communists, and they no doubt lost some of their best troops; three enemy regiments were mauled so badly that they were unavailable for the January 1968 Tet Offensive. In the intense, bloody battle of Dak To alone, Communist fatalities were estimated at 1,455 enemy were killed.

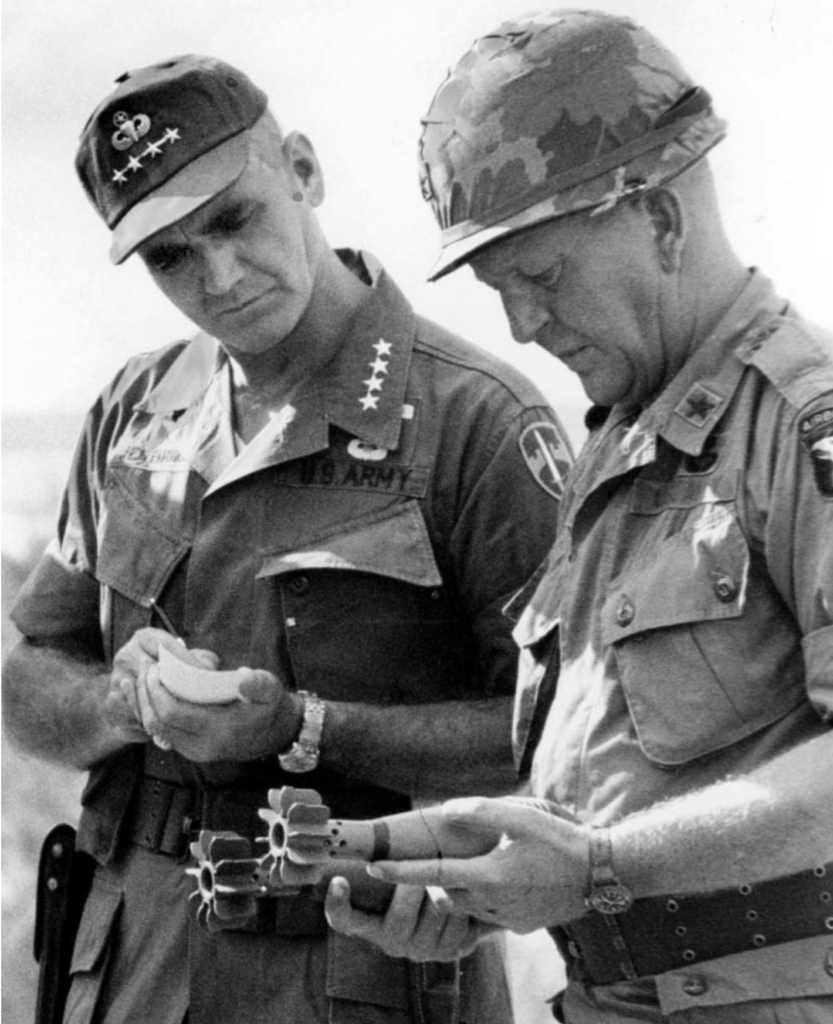

However, at the operational level, these battles achieved the intent of Giap’s plan by diverting General Westmoreland’s attention to the outlying areas and away from the urban target areas that would be struck during the Tet attacks.

In late December 1967, intelligence indicates a significant enemy built-up in the Khe Sanh area.Westmoreland, his staff, and the White House decided that this build-up signified that the enemy’s main effort would take place at Khe Sanh. In anticipation of the big battle, Westmoreland began ordering large numbers of American units north, leaving urban areas vulnerable to attack.

On January 21, 1968, North Vietnamese artillery began large-scale shelling of Khe Sanh followed by renewed heavy fighting in the hills surrounding the Marine base. This surge of enemy attacks confirmed Westmoreland’s assumption that Khe Sanh was the focal point of a new Communist offensive. But he was mistaken. It was a ruse planned by Giap.

In the early morning hours of January 31, when the combined forces of the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, a total of over 84,000 troops, struck with a fury that was breathtaking in both its scope and suddenness. In attacks that ranged from the DMZ all the way south to the tip of the Ca Mau Peninsula, the NVA and V.C. struck 36 of South Vietnam’s 44 province capitals, 5 of its six largest cities, 71 of 242 district capitals, and virtually every allied airfield and key military installation in the country.

In one of the most spectacular attacks, 19 V.C. sappers conducted a daring raid on the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, holding it for hours. Elsewhere in Saigon, V.C. units hit Tan Son Nhut Air Base, the South Vietnamese Joint General Staff headquarters, and a number of other key installations across the city.

Of all the battles, the longest, bloodiest and most destructive was fought over Hue, in central Vietnam. Hue was also a battle where the Communist troops massacred many South Vietnamese civilians. Many were found in mass graves, the victims of what one former Vietcong official called ”revolutionary justice.” Marines, Army and ARVN soldiers had to be sent in to retake the city in almost a month of bitter house-to-house fighting.

By mid-February or two weeks into the offensive, the Pentagon was estimating that enemy casualties had risen to almost 39,000, including 33,249 killed. Allied casualties were placed at 3,470 dead, one-third of them Americans, and 12,062 wounded, almost half of them Americans.

Tactical Victory Thus Became a Strategic Defeat for the United States

The images and news stories of the bitter fighting seemed to put the lie to the administration’s claims of progress in the war and stretched the credibility gap to the breaking point. The tactical victory thus became a strategic defeat for the United States, convincing many Americans that the war was a lost cause.

CBS television news anchor Walter Cronkite, who had witnessed firsthand the vicious fighting at Hue, no doubt voiced the sentiment of many Americans when he exclaimed, “What the hell is going on? – I thought we were winning the war.”

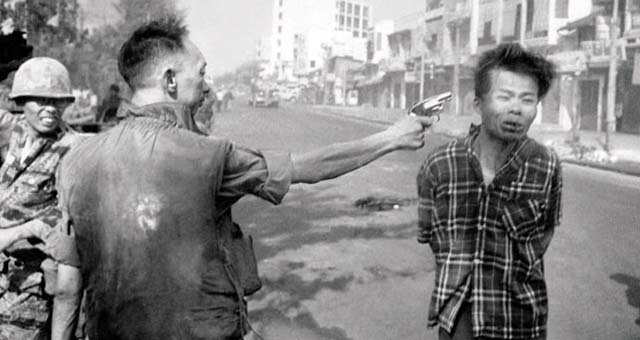

But perhaps nothing captured the horror of the Tet Offensive and the war itself more than the photograph of South Vietnam’s national police chief, pistol in an outstretched hand, executing a suspected Vietcong guerrilla with a bullet through the head on a Saigon street as fighting raged in the city.

In truth, the Tet Offensive, as it unfolded during the next weeks and months, turned out to be a disaster for the Communists, at least at the tactical level.

While the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong enjoyed initial successes with their surprise attacks, allied forces quickly overcame their initial shock. They responded rapidly and forcefully, driving back the enemy in most areas. The first surge of the initial phase of the offensive was over by the end of February, and most of these battles were over in a few days. There were, however, a few notable exceptions – fighting continued to rage in the Cholon, the Chinese section of Saigon, at Hue, and also at Khe Sanh – battles in which the allies eventually prevailed as well.

In the end, allied forces used superior mobility and firepower to rout the enemy troops, who failed to hold any of their military objectives. Additionally, the South Vietnamese troops, rather than fold, as the North Vietnamese had expected, performed reasonably well. As for the much anticipated general uprising of the South Vietnamese populace, it never materialized.

During the bitter fighting that extended into the fall, the Communists sustained staggering casualties. Conservative estimates put their losses at more than 40,000 killed in action, with an additional 7,000 captured. By September, when the subsequent phases of the offensive had run their course, the Viet Cong, who had borne the brunt of the heaviest fighting in the cities, had been dealt a significant blow from which they never really recovered. The major fighting for the rest of the war would be done by the North Vietnamese Army from late 1969 until the end of the war.

The casualty figures during Tet for the allied forces were much lower, but they were still high. On February 18, MACV posted the highest U.S. casualty figure for a single week during the entire war – 543 killed and 2,500 wounded. The total U.S. killed in action figures for the period February to March 1968, were over a thousand. These casualty figures continued to mount as subsequent phases of the offensive extended into the fall. By the end of the year, the U.S. killed in action for 1968 totaled more than 15,000.

Gen. Westmoreland Had Told That The War Was Near An end

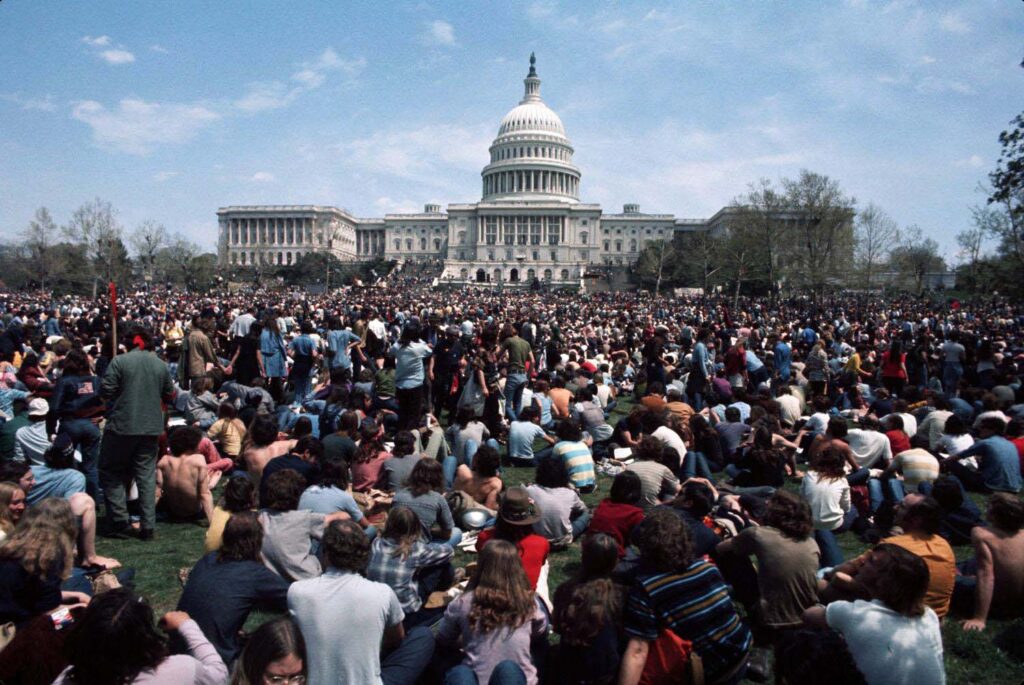

Allied losses combined with the sheer scope and ferocity of the offensive and the vivid images of the savage fighting on the nightly T.V. news stunned the American people, who were astonished that the enemy was capable of such an effort. President Lyndon Johnson and Gen. Westmoreland had told them only two months before that the enemy was on its last legs and that the war was near an end. The intense and disturbing scenes depicted in the media told a different story – a situation which added greatly to the growing credibility gap between the people and the administration. Having accepted the administration’s optimistic reports, but now confronted with a different reality, many Americans concluded that we were losing or at best locked in a bloody stalemate with no end in sight.

The Tet Offensive is generally considered to have ended February 25, when the last Communist units were dislodged from the ancient imperial citadel at Hue. But the struggle in Vietnam was to continue for another seven years. Eventually, a frustrated and war-weary United States withdrew, and, in the end, Communist North Vietnam’s army rolled over the demoralized forces of South Vietnam.

It is stunning and a crime to refer to the “Military Intelligence” submitted to Westmoreland on enemy troop build up and their supply line prior to the Tet Offensive.

Whoever it was in charge of Intelligence should have been court martialed for incompetence.

All this “Build Up” activity taking place in a relatively short period of time prior to the offensive.

“Military Intelligence” was an Oxymoron in this event.

I have learned, never trust the media for accurate information. Today, especially today, people who were once journalist have traded objectivity for propaganda. The bottom line is we let a third world country seemingly defeat a global super power, what sense does that make?. Maybe the objective was not to win the war but to divide another country into communist v capitalist for all the world to see the difference.