The A Shau Valley is a rugged, remote passageway near the border of Laos and the Ho Chi Ming Trail in Thua Thien province. It runs north and south for twenty-five miles. It’s low, mile-wide, flat bottomland is covered with tall elephant grass and flanked by two strings of densely forested mountains that vary from three to six thousand feet. Because of its forbidden terrain and remoteness – and the fact it was usually hidden from the air by thick canopy jungle and fog and clouds – it was a key entry point during the Vietnam War for the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) for bringing men and materials in support of military actions around Hue to the northeast and Da Nang to the southwest.

To stop the flow of hardware, food, and soldiers coming through the A Shau Valley, a number of bitter battles were waged by the American Army and Marines. So fierce was the fighting that any veteran who fought there earned a mark of distinction among other combat veterans. But once the Americans achieved their objective, they did not remain in the valley for very long. U.S. strategy for fighting the enemy did not include occupying remote and sparsely populated areas.

That enabled enemy survivors to flee back to their safe haven across the Laotian border, where they waited until the Americans deserted the battlefield. Satisfied the Americans were gone, they infiltrated back into the valley, picked up where they left off and relaunched their vital resupply mission.

Dominating the western end of the valley next to Laos and the Ho Chin Ming trail loomed a solitary ridge named Dong Ap Bia, towering some 937 meters above sea level. Snaking down from its highest peak were a series of ridges and fingers, one of the largest extending southeast to a height of 900 meters. The entire mountain was a rugged, uninviting wilderness blanketed in the double-and triple-canopy jungle, dense thickets of bamboo, and waist-high elephant grass.

In May 1969, Operation Apache Snow was launched, and like previous allied operations, its goal was to limit enemy infiltration from Laos that threatened Hue and Da Nang. The ensuing bloody battle was the infamous ten-day Battle of Hill 937, or for those who fought there, cynically dubbed Hill 937 “Hamburger Hill” because it reminded them of a meat grinder.

The operation kicked off on May 10, 1969, with heavy concentrations of pre-assault firepower, including heavy artillery, napalm, and B-52 “Arc Light” airstrikes of suspected enemy positions. But this time was different. Rather than retreat from the area, the enemy chose to defend his dug-in positions, which meant eventually his positions had to be assaulted by infantry with the inevitable high casualties.

When the fires were lifted, elements of Colonel John Conmey’s 3rd Brigade of the 101st Airborne landed by helicopter in various predesignated landing zones scattered throughout the valley.

Among his forces were the 3rd Battalion 187th Infantry (3/187) commanded by Lt. Col. Weldon Honeycutt and 1st Battalion 506th Infantry (1/506) under the command of Lt. Col. John Bowers. Supporting them was the 9th Marines Regiment and the 3rd Battalion 5th Cavalry Regiment, as well as elements of the Army of Vietnam (ARVN).

Americans and ARVN are Concentrated in the A Shau Valley

Describing the operation as a reconnaissance in force, Conmey’s strategy was for his five battalion to search their assigned sectors for PAVN troops and supplies. The 9th Marines and the 3/5th Cavalry were to conduct reconnaissance in force toward the Laotian border while the ARVN units cut the highway through the base of the valley. The 501st and the 506th were to destroy the enemy in their own operating areas and block escape routes into Laos. As his troops were airmobile, Conmey planned to shift units rapidly should one encounter strong resistance. In this way, Conmey could reposition his forces quickly enough to keep the PAVN from massing against any one unit.

Contact on the first day Americans and ARVN were in A Shau Valley was light but intensified the following day, May 11, when the 3/187th approached the base of Hill 937. Sending two companies to search the north and northwest ridges of the hill, Honeycutt ordered Bravo and Charlie companies to move towards the summit by different routes. Late in the day, Bravo met stiff PAVN resistance and were forced to fall back.

Helicopter gunships were brought in for support, but the gunships mistook the 3/18 7th’s staging area for a PAVN camp and opened fire, killing two and wounding thirty-five. This was the first of several friendly fire incidents during the battle as the thick jungle made identifying targets difficult. Following this incident, the 3/187th retreated into defensive positions for the night.

Over the next two days, Honeycutt attempted to push his battalion into positions where they could launch a coordinated assault. This was hampered by difficult terrain and fierce PAVN resistance. As they moved around the hill, they found that the North Vietnamese had constructed an elaborate system of bunkers and trenches. Seeing the focus of the battle shifting to Hill 937, Conmey moved Bowers’ 1/506th to the south side of the hill. Bravo Company was airlifted to the area, but the remainder of the battalion traveled by foot and did not arrive in force until May 19.

On May 14 and 15, Honeycutt launched attacks against PAVN positions with little success. The next two days, elements of the 1/506th probed the southern slope. American efforts were frequently hindered by the thick jungle, which made air-lifting forces around the hill impractical. As the battle raged, much of the foliage around the summit of the hill was eliminated by napalm and artillery fire, which was used to reduce the PAVN bunkers. On May 18, Conmey ordered a coordinated assault with the 3/187th attacking from the north and the 1/506th attacking from the south.

Storming forward, Delta Company of the 3/187th almost took the summit but was beaten back with heavy casualties. The 1/506th was able to take the southern crest, Hill 900, but met heavy resistance during the fighting.

Later that day, the division commander of the 101st Airborne, Major General Melvin Zais, arrived and decided to commit three addition battalions to the battle as well as ordered that the 3/187th, which had suffered 60% casualties, be relieved. Protesting, Honeycutt was able to keep his men in the field for the final assault.

Landing two battalions on the northeast and southeast slopes, Zais and Conmey launched an all-out assault on the hill at 10 am on May 20. Overwhelming the defenders, the 3/187th took the summit around noon, and operations began to reduce the remaining PAVN bunkers. By 5 pm, Hill 937 had been secured. Eleven days later, on May 28, the Americans and ARVN left A Shau Valley.

American losses during the ten-day battle totaled 72 KIA and 372 WIA. Losses incurred by the 7th and 8th Battalions of the 29th NVA Regiment included 630 dead (discovered on and around the battlefield), including many found in makeshift mortuaries within the tunnel complex. Yet no one could count the NVA running off the mountain, those killed by artillery and airstrikes, the wounded and dead carried into Laos or the dead buried in collapsed bunkers and tunnels.

The Overall Result was of Hamburger Hill was the Frustration

The battle of Hamburger Hill was similar to other engagements during the war. Enemy losses were much higher than American casualties, the enemy retreated without pursuit by American or ARVN forces, and the battlefield was abandoned 11 days after the end of hostilities. Being the most severe and costly battle going on in Vietnam at the time, it also attracted significant media attention.

Much of the coverage pointed out the difficulty and slowness the airborne troops were taking the enemy positions and the high number of casualties they took each time they assaulted the hill.

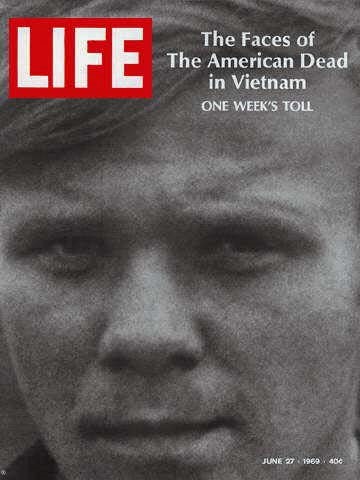

In its June 27 issue, Life Magazine published the photographs of 241 Americans killed in one week in Vietnam; this is now considered a watershed event of negative public opinion toward the Vietnam War. While only five of the 241 featured photos were of those killed in the battle, many Americans had the perception that all of the photos featured in the magazine were casualties of the battle.

The overall result was of Hamburger Hill was the frustration of achieving an overwhelming battlefield success without any indication that the war was being won. To many, this frustration suggested that such battles were isolated events that were unrelated to any eventual policy goal. Consequently, Hamburger Hill became the subject of passionate public debate, focusing on the decision to capture Dong Ap Bia regardless of the casualties and irrespective of its marginal significance in terms of the reasons why the United States was in Vietnam.

The United States Congress also spoke against the war. Several influential senators stood before their peers, severely criticizing the military leadership and calling the operation “senseless and irresponsible.” Their chorus of disapproval was seen as part of a growing public outcry over the U.S. military policy in Vietnam. This led to further outrage in America over what seemed a senseless loss of American lives.

The controversy of the conduct of the Battle of Hamburger Hill led to a reappraisal of U.S. strategy in South Vietnam. As a direct result, to hold down casualties, General Abrams discontinued a policy of “maximum pressure” against the North Vietnamese to one of “protective reaction” for troops threatened with combat action.

While the coverage by the media was highly critical of the tactics and the leadership, newspapers, and television often applauded the honor and courage of the foot soldiers who bravely followed their orders knowing there was a very good chance they could be killed or wounded every time they assaulted the hill.

In 1987, the movie Hamburger Hill directed by John Irvin, hit the American theaters. In it, the horrors – and futility – of the Vietnam War came brutally to life through the eyes of 14 American soldiers of 101st Airborne Division as they attempt to capture a heavily fortified Hill 937 under the PAVN control. In the opinion of most Vietnam combat veterans, the movie was the most realistic depiction of deadly combat.

On the website below is an extraordinary 27-minute film on two desperate battles. One in the A Shau Valley early May 1969, which follows elements of the 101 Airborne Division’s 3rd Brigade during the ten-day battle of Hill 937 (Hamburger Hill). It features Sgt. Arthur Wiknik. The other takes place two months earlier in Mach 1969 at the Rockpile. In it Company C, First Battalion Fourth Marines is attacking Hill 484. Featured is the company’s executive officer, 1st Lt. Karl Marlantes, who earned a Navy Cross for his actions on Hill 484. Marlantes is the author of ‘Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War’ and ‘What It Is Like To Go To War.’

Good article, but it is “Ho Chi Minh” not Ming..

Served as Brigade FA Liaison Officer for this operation. Flew with a FAC to try to adjust fire from the New Jersey, but the range was to far. If memory serves, HH was the lower of two hills, the taller one contained a FA firebase, but memory does fade, praise God!

friend of mine was in that battle with 101st….he was medivacced after 5 days of the 10 day siege