PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

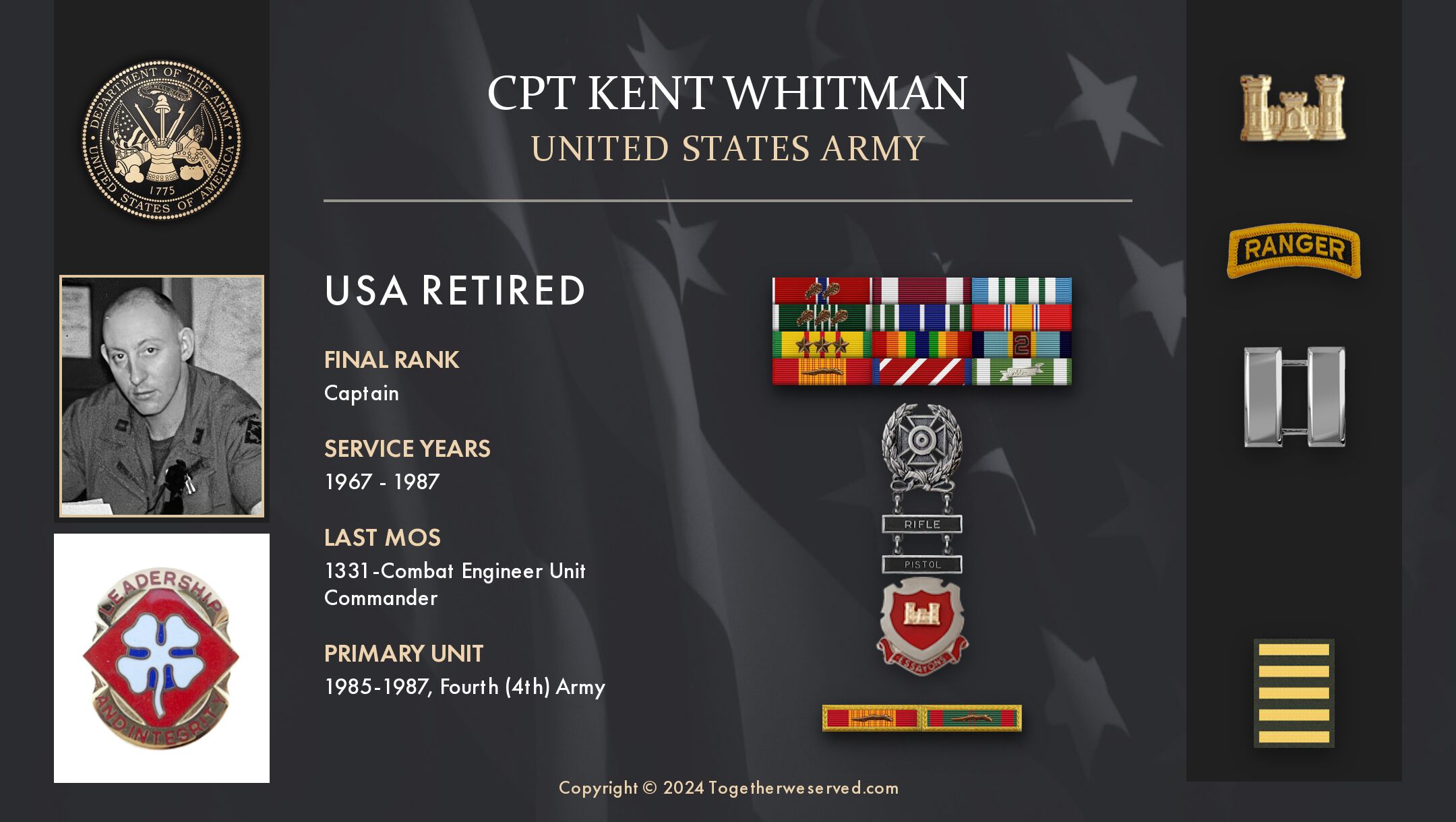

The following Reflections represents CPT Kent Whitman’s legacy of his military service from 1967 to 1987. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Army.

Vietnam cranking up made it easy for me to select ROTC as my elective course while attending the University of Mass Amherst with a college deferment. We need the draft back. I knew I would be called to go after college, so I decided to do it as an Officer. I did well in ROTC, so I was offered a Regular Army Commission instead of the Reserve commission.

Initially, I went to college to become a teacher because I was impressed by a teacher in high school and wanted to be like him. But while in ROTC, I was very impressed with the Army Officers and NCOs in the program and decided on a career in the Army.

I am now back teaching in college.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

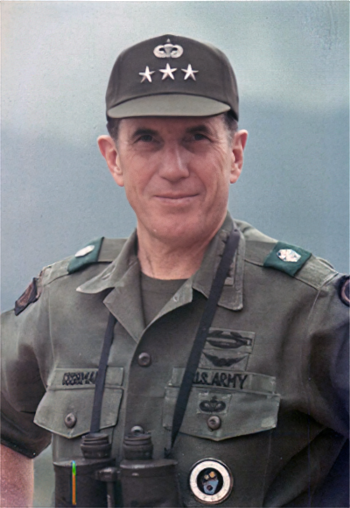

Like I said in the previous question, I decided to make the Army a career accepting the Regular Army Commission. I spent three days and 20 years in the Army, joining on 28 July 1967 and retiring on 1 August 1987.

In the last few years of my service, I worked for the Army as a Captain. After all, I was not selected for promotion to Major resulting in not-so-good OERs because I would not lie and tell the truth even though my superiors did not want to hear the truth. And because the Army was in a drawn-down mode. I was a 2LT for a year, a 1LT for a year, and a CPT for 18 years. They needed my service as an Engineer, so I was twice selected by the Secretary of the Army for selective retention.

I think when I retired, I was the ranking Engineer CPT in the Army. So I left for a couple of reasons. I originally planned only to serve 20 years because I was terminated for lack of promotion. I had four commands, one in Germany, 2 in Vietnam, and 1 with the 101st at Campbell. Deployed five times, Germany, Vietnam, Turkey, Honduras, and Egypt.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

I will begin this response with operations while commanding the 568th Light Equipment Engineer Company in Hanau, Germany, in 1969. My previous assignment was in the 54th Combat Engineer Battalion stationed in Wildflicken, Germany, as a Platoon Leader. The 568th was supporting the 54th doing Combat Engineer project work at Wildflicken. Also stationed at Wildflicken was the 2/15th Infantry Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division. At the time of my visit to Wildflicken to visit my men in the field, the Infantry unit was conducting airmobile operations using CH37 helicopters, which had their big engines on the side of the helicopter.

When I finished my ground visit by jeep, I returned to the airfield to get my helicopter, a CH34, to ride back to Hanau. My bird was not at the airfield, so I asked the ops people where it was. They told me it was on a recovery operation because one of the airmobile birds had crashed with about 13 troops on board. One was killed, and 11 were injured. The CH37 had lost cyclic control at about 100 feet and came down on its side with one of the engines sitting on top of the wreckage. It was in a field not far from the Wildflicken airfield.

When my CH34 returned to the airfield with some of the badly injured, I jumped in and was given some morphine to take out to the doctor on site. When I arrived, there were two left still crushed under the wreckage. I was told they had a 5-ton wrecker en route to lifting the helicopter so the remaining two could be extricated from the wreckage. I told them the 5-ton wrecker would not do the lift since the helicopter weighed about 21,000 pounds. I suggested they request a 20-ton rough terrain crane from the 54th. They did make that request, and it was dispatched.

While waiting for the crane, I asked the Infantry unit members gathered on-site to get me all the salt packs out of their C-Rations. When the crane arrived, I instructed the Engineer Maintenance Warrant who came with the wrecker to rig the helicopter for lifting, which he did. Then I told him to stand in the cab with the operator and not to let the operator set the break on the lift mechanism. If he set the break, the crane might settle a few inches, and we could not afford that to happen while the Doctor and I were under it. I told him to have the crane operator just hold the lift, slipping the clutch, and for the Warrant to sprinkle the salt on the crane clutch so it would continue to hold the lift without slipping. The Doctor and I crawled under the helicopter to pull the two remaining soldiers free while the Warrant and crane operator lifted it up just enough so we could get under it and pull them out.

All this time, my pregnant wife back in Hanau had heard the news of a helicopter crash and did not know if it was my helicopter. I had the ops folks at Wildflicken call Hanau and tell them I was all right and en route back to Hanau.

Another more humanitarian operation was also with the 568th LE Engineer Company. We had a community support request from a local town asking for some equipment to clear a field to create a fire practice field where the town fire department could practice burning things and putting them out. The project was approved, and we built the Fire Platz field. The town was holding an

October Fest with fun and games, live entertainment, and lots of schnapps and beer. As a reward, they gave me 2,500 drink tickets to give to the men of the Company. With about 120 men in the Company, that would equal about 21 drink tickets per person. We made arrangements to shuttle the men to and from the Company and the field, giving the NCOs the tickets to hand out and courtesy patrols to keep the men under control if they got too much under the influence. All went well, and the wife and I attended and could not use any of our tickets as the Germans in charge of the event would not let us use them. They bought all of our drinks. We had fun singing rum papa drinking songs.

It was a great community relations event. The Germans were very grateful for our effort, and my men were very happy to drink the beer.

When I arrived in Vietnam, I was assigned to the 169th Engineer Battalion Construction stationed on the Long Binh compound. I was the Commander of the HHC. The line companies were strung out along QL20, building the road from QL1 North to the MRIII — MRII border.

Most units residing on the Long Binh compound with combat troops were given the mission on a rotating basis to conduct Search and Destroy operations outside the perimeter. When it was our turn, Battalion S3 gave me the task of using HHC clerks, and maintenance personnel conducted some training with the men about how we would conduct the operation. Many of them had never done such an operation, although all Engineer troops are trained and required to operate as Infantry when the need arises. We went outside of the wire on patrol and ran into what we believed to be a weapons cache with tunnels. We secured the site and called in for a dozer to investigate the site. The dozer was digging out the site where I was standing at the side watching the operator. I saw a large black 155 Howitzer round under the dozer’s blade. Yelled to stop the operator from going any further, he called in for EOD support, and they arrived to find out it was a fused shell that had not gone off. We moved back, and they detonated it with other explosives. We found no weapons at the site. We then finished our patrol with no further incidents.

Another operation while serving with the 169th Engineer Battalion in early 1970 was when the unit was tasked with removing the improvised minefields that had been installed around the perimeter of the Long Binh compound back during the VC Tet Offensive in 1968. The mines, primarily improvised, were placed in tanglefoot barbed wire out to about 100 yards in front of the major concertina wire. Most were placed on top of the ground. Many were to be command detonated from bunkers back inside the major concertina wire. Most deteriorated to the point of being unrecoverable and dangerous to deal with or touch. Five of us, Engineer Captains, were given large areas to set up explosive ring mains using C4 explosives and set cord that would be initiated with nonelectric strikers and fuse cord. When all the ring mains were set up, we ignited our fuse. All but mine worked as my igniter failed to set off the fuse. I had to go back through the wire and get a cigarette lighter, then go back out to ignite the fuse. I got back to the bunker and undercover before they started to go off. Behind where we were working was the ammo dump. They thought they were under attack as earth, rocks, and shrapnel fell from the sky inside the ammo dump. They set off the attack alarm, so the entire Long Binh compound went on alert. We called in and told them that it was only our detonation of the minefields and not an attack. That operation was a blast!

Another memorable operation occurred in 1970 while I was Commander of the 544th Construction Support Company stationed on Nui Soc Lu in Vietnam. The unit was attached to support the 169th Engineer Battalion Construction. It was the second-largest industrial site in Vietnam at the time. We had six major rock crushing units, a 120-ton Barber Green Asphalt plant, an attached Quarry Platoon, and hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of equipment to run such an operation. The unit was stationed on a mountain banana plantation next to a resettled North Vietnamese town where it was assumed there was a rock under the ground. Unfortunately, the assumption was not true. We had moved over 200 feet of overburden before hitting any major rock formation. We were making an inch minus rock for the asphalt and 2-inch minus for the base course of the road the line companies were building. I lost one man during a monsoon rainstorm. He was the operator of a bucket loader loading the line company trucks with 2 inches minus rock when the storm hit. He and five truck drivers with one NCO cuddled under a crane in the pit area to get out of the torrential rain. The crane boom was all the way down. Unfortunately, a lightning bolt hit the crane boom and went down through the crane, frying all the wiring. My bucket operator must have been leaning up against the crane metal, so the electricity from the lightning bolt killed him. The others received shocks and were knocked about but survived the incident.

My rock and asphalt operation was critical to the Battalion’s mission. We were being watched very closely by the Commanders above me and the Corps Commander, who would visit me often. We had to report every hiccup in our operation. One night, we lost (got torn up from use) a 24 inch wide, 200-foot long conveyor belt which halted our 24/7 operations.

At the time, I was in Long Binh picking up pay for the men of the Company. At about 2100 hours, my Battalion Commander ordered me to return to the Company at Nui Soc Lu to manage the repair operations. On the way by jeep back to the Company, my jeep driver and I were ambushed in the dark. I told the driver to put his foot in the carburetor and not stop until we reached the Company. I emptied my M16 magazine, along with a second magazine, and pumped out two rounds from our M79 grenade launcher before we got through the kill zone. Fortunately, neither of us was hit.

I was very pissed at my Battalion Commander for sending us out at night and got on the radio back to the Battalion in Long Binh and let him know how I felt. The battalion wanted to know how long we would be down repairing the conveyor belt. We estimated that we would be back up operational by 0700 hours the following day. Early in the morning, we were nearing completion of the repairs when we discovered we had measured and cut the belt 20 feet short. So we had to cut another 20 feet of belt and make a second splice, which took us another half hour. At 0700 hours, a helicopter arrived with the Corps Commander (BG), the Brigade Commander (COL), and my Battalion Commander (LTC). The General had made several visits to our operation, so he was very familiar with me. He asked me why we were running late from our estimate of being back up and running at 0700 hours. I told him about our mistake and assured him we would be running in another half hour or so. He was fine with that explanation, saying, “Thanks, Whit, see you again for coffee soon.” So he turned and headed back to his helicopter. The other two, one on each arm of mine, grabbed me and asked why, I told the General we screwed up and cut the belt 20 feet short. I jerked my arms loose from the two Colonels and said very loudly, “What, did you want me to lie to the General?” They were pissed and followed the General back to his helicopter. We were up and operational shortly after they left.

On another occasion, the Deputy Brigade Commander was visiting my operation. He had a Signal Corps 2LT as his aide. The 2LT took one look at our rock dryer and went and told the Colonel we were running the dryer too hot and were melting the firebrick in the orifice of the dryer where the flame entered the dryer rotating drum. We were running the dryer at about 600 degrees. The firebrick does not melt until about 2100 degrees. The Colonel told me to turn the dryer down. I explained that if I did that, we would be getting white caps in the asphaltic concrete coming out of the pug mill where the rock is mixed with the liquid asphalt. Any moisture on the rock and the asphalt would not stick to it, hence white caps. He would not accept that explanation and said it was a direct order to turn the flame down. I ordered my 1LT, who ran the asphalt plant crew, to turn it down. He did as I told him.

Shortly after, the Colonel and 2LT left the compound. What was happening was the fine rock dust that accumulated in the orifice was melting and running out onto the ground. The firebrick was not melting. This was very normal, and when not producing asphalt, we had to chip this molten rock away from the bricks. As soon as the Colonel left the compound, I called my Battalion S3 on the radio and told him I would be sending bad asphalt up the road because the Colonel had ordered me to turn the dryer down. He ordered me not to send any bad asphalt up the road and to shut down the asphalt plant for the day. We did that.

Pissing off all these senior Engineer Officers and another in the 101st is probably why I never got promoted to Major.

After leaving the 544th, I was reassigned to MACV Team 96 in the Delta (MRIV) stationed at Can Tho. I was the Deputy Engineer Advisor working under a Colonel who was a fantastic boss. Our Deputy MRIV Advisor was BG Jack Cushman, who was also an Engineer. He would take me with him as he flew around the Delta looking for a firefight where he would land to find out how the fight was going. He flew his own helicopter and spoke fluent Vietnamese. One night at about 0200 hours, his aide came and woke me up saying the VC had blown a bridge over QL1 south of Saigon, and the General was sending his Huey helicopter to take me out to the site to assess the damage and figure out what needed to be done to repair it. What a freaking night that was.

We landed on the road south of the bridge only a few meters away, blowing thatched roofs off the nearby huts. The local Vietnamese Combat Engineers were already on-site, and their American Engineer Advisors were making plans for the repairs. I served for a while, then went back to Can.

Tho headquarters and had breakfast with BG Cushman, telling him what was happening. The bridge was a three-span bridge with six 21 inch I beams as the support structure for all three spans. The VC floated down the river underwater with explosives, placing them inside the mid-span 3 I-beams on the Eastside and the inside of the three I-beams on the Westside. When they detonated them, the outside ones were set off first, and in a fraction of a second, the next ones were detonated. Finally, the inside ones were detonated in a fraction of a second. This separated the bridge like opening a book. Three I-beams went upstream, and three went downstream. The VC knew precisely what they were doing. The Vietnamese Regional Commander was on-site and allegedly killed the Platoon Leader who was in charge of the security detail and the two Vietnamese soldiers who were asleep on duty when the bridge was blown.

While in the Delta advising the engineers, I went to Chi Lang Mountain, one of the seven sister mountains located in the Mekong Delta. A small unit of Vietnamese engineers was building a fire support base on top of the mountain where they were going to put some 105 Howitzers that would support combat operations in the area. I had a Huey come to pick me up at the airfield at Chi Lang village. I went to the Warrant Officer to brief him on what I wanted to be done, and he told me to go around the AC and brief the LTC, who was the AC Commander and had not flown any combat operations. I found out later that the LTC was a Saigon desk jockey just out to get some stick time to get his flight pay. I had flown with the Warrant before and trusted him, but I did not trust the LTC. But I went around the AC, and with a map, I briefed the LTC on how to approach the very small landing pad on top of the mountain from the South. The VC had caves on the north side of the mountain with 51 caliber radar-controlled machine guns ready to take down any AC approaching the mountain from the north. I told the LTC about that a short time before they got two slicks out of a lift of 5, passing the mountain in the North. The LTC acknowledged my instructions, so off we went.

Shortly after we took off, I talked to the Vietnamese engineers. I was getting up to the worksite when I looked up, and we were headed directly toward the caves. I pulled my Colt .45, put it on the LTC’s flight helmet, and ordered him to immediately turn the AC over to the WO. He yelled at me that he would have me court-martialed. I cocked the hammer on the .45 and said, OK, but you will not get me killed by the 51s in the caves; let go of the controls. The WO took command of the Huey, and we went to the top of the mountain from the south. When I got back to Can Tho, I told my boss and BG Cushman what had happened. BG Cushman said not to worry about it and that he would handle it if anything came of it. I never heard of it again.

In April 1974, I was taken out of the Engineer Advanced Officer Course and sent to Egypt with a small group of Engineers and Ordnance Disposal Soldiers. We were part of Task Force 65, and our unit was designated TF 65.6 Nimbus Moon Land. We were given the mission of assisting the Egyptian Engineers in removing landmines and ordnance from around the Suez Canal after the October 1973 Yom Kippur War. During the peace talks, Dr. Henry Kissinger told President Sadat that the US would provide Army Engineers and Ordnance Disposal personnel to assist the Egyptian Engineers in removing the landmines from around the Suez Canal and some out in the Sinai Peninsula.

I was in command of a Battalion Advisory Team consisting of myself, 2 Special Forces Engineers E8s, 1 Regular Combat Engineer E7, and 1 Special Forces Medic E8. We were assigned to advise the Egyptian Engineer Battalion working to clear mines along the Canal south of the great and little bitter lakes to Port Taufiq. I got the opportunity of meeting and talking with President Anwar Sadat when he came to Suez City to see the war damage and talk with the people about reconstruction. We talked for about 15 minutes, during which time I gave him my American Flag that I always carried with me when deployed. He was genuinely moved by this offer. Late that year, I received a Christmas card from him signed by Anwar L. Sadat.

On one operation while out in the Sinai, we removed 30,000 landmines from one minefield surrounding the Israeli gun position at a place called Yum Musa. That place is now a war monument and museum.

After my little trip to Egypt, I was reassigned to the 326th Engineer Battalion, 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, KY. There I was first assigned as Battalion S2 or Intelligence Officer. Then I was given command of ‘A’ Company with about 110 Officers, NCOs, and men. The Company conducted many training exercises supporting the 1st Infantry Brigade, 101st Airborne Division. On one exercise, I moved the entire Company, all personnel, and all equipment (even the cooks), by helicopter from the Fort Campbell compound to the field training location. At the time, I was the only one to accomplish that complex feat.

After serving my year as Commander of ‘A’ Company, I was reassigned to the G3 Training Staff at the 101st Division Headquarters. There I introduced the Division to the M56 Scatterable Mine Dispensing System. I even got the equipment shipped in and installed on a UH1D (Huey) helicopter. I got some training mines and put on a demonstration for the Division Senior Staff Officers. They then adopted the new system in the Division. While serving in the 101st G3 Training section, I was deployed to Germany on a Reforger training exercise. I served as a night Operations Officer and directed some 11,000 troops during the night exercises. Colin Powell (then a Colonel) was in the Division while I was there. He is a great officer.

From the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, KY, I was assigned to TUSLOG Det 4, Sinop Turkey, in November 1977, serving there until October 1978. My wife and two young daughters stayed in Government Quarters at Fort Campbell while I went off to Sinop. I was assigned as the Facility Engineer, taking over from Tim Coffee. The installation was shut down in what the Turks called limited operations. We were not allowed to operate any intelligence equipment in full operations mode. The Congress of the United States placed an embargo on the support of Turkey due to the Turks using US weapons systems when they went into Cyprus in 1974. The Turks, in turn, placed an operational embargo on all intelligence operations from installations in Turkey such as Sinop and TUSLOG Det 4. We were not allowed to move a chair from one office to another without the Turkish Commander’s permission in writing. My job as a Facility Engineer was as a Contracting Officer for the US Army overseeing the Civilian Engineer firm contracted to operate the facilities and keep it in a status quo state of repair. Tim Coffee, my predecessor, had just about finished building a 5,000-foot concrete runway down at the airfield. There was still a 2300 foot PSP runway operation. Part of my job was to apply for and get the new runway approved and registered by the US Air Force. The new runway, which appears to be operated according to Google Earth photos, was complete with lights. However, the airfield did not have the necessary radar systems, so all flights in and out were visual. Keep in mind I am not an aviator and do not know the technical terms for all the instrument landing equipment that we did not have.

The Civilian Engineer firm and their Turkish employees were very good at what they did. They worked very hard at keeping the facilities operating within the limits of the embargo. Work during the week was generally very interesting and uneventful, with some exceptions. I will get to it later. My off-time was spent playing basketball in the gym until I aggravated an old injury. The Doc, CPT Patterson, stopped me from playing anymore and took me to an AF orthopedic surgeon in Ankara or Adana. I ended up having my right ankle reconstructed just before I went home on mid-tour leave.

After the operation and a few days of recovery in the AF Hospital, I returned to limited duty on crutches and tried to be normal and do my work; however, I was so juiced up on pain meds I was having trouble functioning. My boss, LTC Richard Olson, the S4, told me to go to my quarters and stay there until I could perform. Later we had a good laugh over some of my actions while high on pain meds. I was told I could bring a shotgun on tour, so I packed my 16 gauge HR Topper, single barrel hammer shotgun, and ammo to hunt birds and wild boar. All the other hunters had big 12 gauge pump guns and laughed at my little single 16 gauge barrel, but the first time we went out for Russian Quail, out toward the Hippodrome, I bagged the first two that went up before anyone else could shoot. Needless to say, the others were impressed. I hadn’t told them that I had been given that gun for Christmas when I was about ten years old and had bagged many Pheasants and Grouse with it. We would bag several each time out and then have a cookout at the barracks. We’d get a chance to go wild boar hunting with the Turks. When the Turks saw my 16 gauge, they were very inquisitive about the gauge, as they had never seen a 16 before. Most of them had old Damascus (twisted steel, not bored) barrels in gauges 20 or 12. I carried both buckshot and slugs for my gun. We did not get a boar on that trip but had a fantastic time up in the mountains south of Sinop.

On our way out in the morning, around 0400 hours, we would stop in town and get some freshly baked bread for the trip. A boy was that good. The Turks also told us to bring salt. They could stop in the mountains and pick mushrooms, “huge mushrooms,” to eat. A little salt made them delicious. Another pastime was fishing in the Black Sea. One of the Turkish Firemen had a boat and took me fishing for baby Atlantic-blue, or yellow-fin, Tuna. I think they called them Palamoute or something like that. We would troll for them with long lines with feather flies as bait. When we had a bunch hooked, we would stop the boat and pull them in. We then headed the boat to the sandy shore, built a fire, and cooked and ate them right there. Fantastic memories!

During the cold, windy winter, much of our off-time was spent indoors, drinking (too much), shooting the ball, playing cards, watching movies at the theater, listening to music, reading in the Officer’s Club by the fireplace, and writing home – things like that. One thing I did was to draw caricatures of some of the locals. I did one of the dentists and one of the old American Fire Chief. The dentist was Major Chris Geary, who sold me a 55-pound pull bow he wanted to get rid of. Nice Tooth Fairy!

A few years ago, I ran into Major Geary. He was living in, or near, Wilton, NH, and I have not seen him since, and I believe he was building a house there.

On 20 January 1978, the guys from the airfield came into our office (LTC Olsen and my office) to report that one of the aircraft, a U-21F with five passengers, was overdue from a return flight from Istanbul. They had done all they could do to try and reach the aircraft by radio but had lost contact with them about 1630 hours, as I recall. They feared the worst that the aircraft had crashed in the mountains. The airfield had no radar or beacons, and all inbound flights were visual.

Often, in the mountains, flying was like flying inside a ping-pong ball. They were reporting to LTC Olsen, as he was also the Deputy Commander and was left in charge, as the Full Colonel Commander of the site was home in the States. LTC Olsen asked me to establish a Tactical Operations Center (TOC) and organize a search and recovery operation. We immediately asked the Turkish Commander for any assistance he could provide. I quickly organized some ground search teams, outfitted them with what radios we had, and sent them out in vehicles looking in the direction the aircraft would be coming from. They were to stay in contact with us in the TOC and report anything they felt was important. They searched all through the rest of that night but found nothing. We had requested a helicopter from TUSLOG but were denied because of the poor visibility in the mountains. However, the next day, the Turks provided us with a UH1 (Huey) and crew – now keep in mind the US had given or sold them the helicopter, but, in 1974/75, had stopped giving them any spare parts because of the Congressional embargo – so it was held together with baling wire and duct tape (so to speak). Those Turkish pilots were great. They went out and flew in the sub-optimal weather to look for the downed (we suspected), or lost, aircraft. While at the same time, one of our ground crews got some information from some civilian Turks concerning fire and a crash way up in the mountains the day before and pointed in the direction where they saw it. The team proceeded to try to get to the site, but it was so far off the roads it was not feasible.

We got word to the Turkish Huey crew, and they finally found the crash site, which was not accessible by ground. We finally received the TUSLOG Huey and crew and used it to take Doc Patterson and some MPs for security out to the site. They could only get to about 200 meters from the site, and that odd distance had to be traveled by foot in 10 or so feet deep of snow. Doc Patterson confirmed that all on board were KIA and badly burned. We got body bags and recovered the bodies, bringing them to the airfield. We had arranged for a C130 Medevac to come out of Germany to take them to a hospital and morgue in Germany where Doc Patterson could match their dental records with the bodies. The FAA investigation team arrived in a day or so, and we took them to the site in the TUSLOG Huey. After inspecting the crash site, they determined that one of the twin turboprop engines went in with full power, and the other went in with no power. That aircraft can fly on one engine; however, it crashed about 200 meters from going over the top of the mountain.

The FAA team requested we recover the engine that went in with no power. LTC Olson gave the mission to me. I had the Turkish Engineers make a wooden sled that would hold the 900 pounds of the engine. At the time, I assembled a team of the biggest guys on the Hill (Our station at Sinop was called the Hill), got a 2-ton truck with a ton trailer, and headed to the site. I also had a D7 Bulldozer loaded onto a flatbed and took it with me. We got as close by road as we could, unloaded the dozer and hooked up the trailer with sled in it, and started to walk the dozer up into the mountain. It took us several hours to get there, but along the way, we were met by civilians who assisted in directing us on the way to go.

We were following old roads that went up into the mountains. The Turkish people were very helpful and eager to do so. When we arrived on site, I had the trailer unhooked from the dozer. The men took the sled by hand, pulled it up to the engine we were to recover, and got it loaded and tied down on the sled. While this was happening, I had the dozer operator build a ramp that we could back the trailer up to, so we could slide the sled with the engine onto the trailer. Well, on the way down from its resting place at the crash site, the sled and engine decided to take a path of their own and did not end up where we had built the ramp. So I had to have the dozer operator make another ramp, and we moved the trailer and dozer there and finally, with a lot of grunting and groaning, got the sled with an engine in the trailer. It took us several hours to get back down the mountain to the trucks waiting for us. We swapped the trailer for a 2-ton truck and loaded the dozer on the flatbed. We then cheered and headed back to the hill.

This entire engine recovery operation took us a full 24 hours, and we were all cold, wet, hungry, and tired. The men on this operation were outstanding and performed with the utmost professionalism. I do not recall any of their names, but they performed as a well-organized team and executed their mission flawlessly. Nobody was injured during this challenging mission. Keep in mind these were all clerical personnel or radio/computer operators, not Combat Engineers or Infantry troops.

Now let me get back to the C130 medevac bird. I was down at the airfield when it arrived from Germany and spoke with the AC Commander. He said they had no charts of the place except a 2300 foot PSP runway. I responded in the affirmative. Then he asked me what that long gray thing was that he could see from his cockpit. I said it was a brand new 5,000-foot concrete runway all decked out with lights and painted. He asked if he could land on it. I said I thought he could if he wanted to try. He said there would have to be an emergency landing because his charts only indicated the 2300 foot PSP runway. I indicated that he should have no problem landing on it. He landed, and we loaded the bodies on board, and CPT Patterson strapped in, and again I spoke over the radio to the pilot. This time he indicated that there would have to be an emergency takeoff because he had no charts of the new runway. I think he was hot-dogging it a bit. He taxied to the end of the runway and turned the C130 around, and gave it full throttle with all the brakes on, then he let the brakes go, and he was airborne in about 200 feet.

20 January 1978, U-21F crashed on a return flight from Istanbul with the following KIA:

CW3 James D. Thompson [Pilot]

MAJ Tommy R. Smith [Pilot]

PVT Walter J. Penchikowski [arriving new MP from Keene, NH]; (I had to write his parents)

MAJ Paul G. Schlude [??]

MAJ James R. Smith [Det 4, S3 Operations Officer]; (We were close as he was a Ranger too.)

Later, the FAA investigation found a small pin had failed in the engine, causing it to lose power and fail. It was suspected that when it happened, there was not time enough to react to continue to fly the aircraft on one engine, and they lost altitude, causing them to hit the mountain down 200 feet from the top.

Another major function I had was keeping enough water in our storage tank to allow us normal water use. The US had assisted the Turks in installing a pipeline from an aquifer several miles from Sinop. The water would flow by gravity from the aquifer to cisterns the Turks built in the city. Some water was then pumped from the cisterns up to the hill, while the rest went to the city system.

On the Hill, it was stored in a large water tank used to feed the water system on the compound. When the incoming water from the aquifer was low in the dry summer season, the Turks would go into the pump house and shut off or down the valves used for the water going to the hill. Tim Coffee had built a great visual gauge with three colors on it. When the tank was full (the top 1/3 of the tank), the gauge pointed to green. When it was in the middle third of the tank, it pointed to yellow. And when it was down to be bottom 1/3 of the tank, it pointed to the red. Everyone on the Hill watched that gauge. We had an SOP that provided directions on what water could be used for depending on the gauge color. When it showed in yellow, I would go visit the Mayor in town and ask him to have his people open the valves so we could get more water. This was a political endeavor. Every time I did this, he would want something in return; some cement or other supplies that he could not obtain. So it was a bartering situation. When the gauge showed red, I would go into the pump house and open the valves myself.

I have since become close friends with Dave Swenson, who flew Intel flights in the area long before I was there and had been to Det 4 on the Hill. He lives just a few houses from me here in Keene, NH. He put me in contact with DOOL Diogenes Station Sinop Turkey, where I found one of the Turkish Engineer Supervisors, Abdullah Eren. Abdullah and I communicate via email and on Facebook. Abdullah recalled seeing me at the crash site when the FAA investigators were there, and he was assisting with the security of the site. Shortly after I left the Hill, things were settled between Turkey and the United States, and I understand Det 4 has been fully operational again. I will never forget my tour at Sinop with fondness except for the plane crash and losing those friends. All the men and women there were great people, and I am happy to have served them. We had lots of good times together.

After Turkey, I was reassigned to the New England Division of the Corps of Engineers stationed in Waltham, MA, and I bought a home in Salem, NH. My parents still lived in Massachusetts, so that I would visit them often. Working for the Corps of Engineers in Civil Works was a great experience. I served in three positions, all of which were senior slots way above my rank as a Captain. I first worked in the Operations Division working on wildlife management plans. Later, I became an Assistant Division Engineer and was a Contracting Officer for the Corps and had responsibility for some 31 contracts from minor repairs to major construction projects. These were spread out all over New England, where the Civil Works Dams and Reservoirs are today.

In 1984, I was reassigned to the Army Readiness and Military Region V (ARMR V) at Fort Sheridan, IL, under the Fifth US Army located in Ft Sam Houston, TX. There I worked training the National Guard and Reserve units in a five-state area, IL, WI, MN, IA, and MO. It was about this time when Nicaragua’s Sandinistas kicked up their heels and caused some trouble for Honduras. The Army was conducting some “exercises” (with fully loaded weapons) in Honduras to show US support for Honduras. I got the opportunity to serve as the Joint Military Service Task Force Engineer at Palmerola Airbase. The US government once used Palmerola Airbase (now called Soto Cano) to support its foreign policy objectives in the 1980s. Now the US military uses Soto Cano as a launching point for its war on drug efforts in Central America and humanitarian aid missions throughout Honduras and Central America.

As the Task Force Staff Engineer, I was responsible for coordinating two airfields’ construction and planning, designing, supervising, and managing base construction and maintenance projects employing troops and contract engineers. A Lieutenant Colonel normally filled this position, yet as a Captain, I was given this responsibility. It was an interesting assignment as Congress was closely monitoring all construction projects. My assignment to Honduras was only for six months.

Back at Fort Sheridan, ARMR V was deactivated, and the Fourth US Army was reactivated with the headquarters at Fort Sheridan. I was trained as a World Wide Military Command and Control (WWMCC) Officer and given responsibility for the Top Secret communication system for the 4th Army. I worked with Forces Command to establish a new Top Secret WWMCC facility at Fort Sheridan and the National Guard and Reserve units throughout the eight-state area of operation, the five original states of ARMR V plus MI, IN, and OH. While there at Sheridan, I earned my Master of Arts degree in Computer Resource Management and Management from Webster University out of St. Louis, MO.

I retired at Fort Sheridan on 1 August 1987, after serving two days and 20 years of service to the country.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

My fondest is meeting and talking to President Anwar L. Sadat. At the same time, I was stationed in Egypt with Task Force 65.6 Nimbus Moon Land, assigned the mission to assist ( advise) the Egyptian Engineers in clearing landmines from the banks of the Suez Canal (supposedly only up to 250 meters from the Canal).

I do not have any least favorites. I enjoyed all 20 years of assignments in the Army. For certain, I did not enjoy recovering bodies from the helicopter crash in Germany, or losing a man in Vietnam, or having to recover my friend’s bodies from the plane crash in Turkey. All of those times still haunt me today.

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect back on to this day.

I would have to say not getting promoted to Major and, above all because I would not lie to my Commander while in the 101st Airborne Division hurts the most. I lived by what my father told me, “Son, always tell the truth even if it hurts.” The Battalion Commander is a White House ring knocker and gave me a bad OER because he did not want to hear that things were not all good. He would not accept that problems existed in his Battalion when, in fact, they did. When the 13th Airborne Corps gave my Company the unit tests, my Company tested the highest in the Battalion. It has impacted both my family and me financially.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

I was awarded 3 Bronze Stars for my service in Vietnam.

Citation:

For distinguishing himself by meritorious achievement in connection with military operations against a hostile force from 3 August, 1970 to 7 November 1970 while serving as Engineer Staff Advisor, Delta Military Assistance Command, United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. Captain Whitman displayed outstanding leadership abilities in accomplishing his duties as the principal advisor to the staff of the Engineer, IV Corps, and Military Region 4.

The Vietnamese were always receptive to his advice and guidance and were quick to seek his assistance on difficult problems. His friendly manner, sound judgment, and technical expertise won their confidence. Captain Whitman was particularly instrumental in assisting the Vietnamese staff in organizing flood reporting, forecasting, and recovery operations during the annual monsoon season. He collected the daily gauge readings from the reporting stations and disseminated the flood forecasts to all provinces of the Mekong Delta region. He also assisted the Vietnamese staff in organizing road rehabilitation and repair teams to improve the capability of the total government agencies to maintain and extend the road networks so essential to the pacification and development of the region. He personally coordinated combat support activities involving Vietnamese and United States engineer forces and was instrumental in arranging the training of a Vietnamese land clearing element. His professional competence, personal courage, and leadership contributed significantly to the success of the Delta Military Assistance Command. Captain Whitman’s outstanding achievement was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Army and reflects great credit upon himself and military service.

Bronze Star Medal (First Oak Leaf Cluster)

Citation:

For distinguishing himself by meritorious achievement in connection with military operations against a hostile force during the period January 1970 to December 1970 while serving first as a company commander in the 20th Engineer Brigade, United States Army Engineer Command, Vietnam (Provisional), and later as Engineer Staff Advisor, Delta Military Assistance Command, United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. From January to March 1970, Captain Whitman was the Commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 169th Engineer Battalion (Construction). In this period, he successfully led his unit through both the Command Maintenance Management Inspection and the Annual General Inspection. In recognition of his resourcefulness and management capability, Captain Whitman was named Commander of the 544th Engineer Company (Construction Support). In this capacity, from March to July 1970, he operated one of the largest industrial complexes in Vietnam. He supplied crushed rock and asphaltic concrete to the engineer units constructing the essential lines of communication (roads). From July 1970 to December 1970, as Engineer Staff Advisor, Delta Military Assistance Command, he demonstrated his versatility as the principal advisor to the staff of the Engineer, IV Corps, and Military Region 4. His professional competence, personal courage, and leadership contributed significantly to the success of both the 20th Engineer Brigade and the Delta Military Assistance Command. Captain Whitman’s performance of duty was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Army and reflects great credit upon himself and his military service.

Bronze Star Medal (Second Oak Leaf Cluster)

Citation:

The Bronze Star Medal (Second Oak Leaf cluster) is presented to Captain Roy K. Whitman, 029-32-9736, Corps of Engineers, United States Army, who distinguished himself by outstandingly meritorious service in connection with military operations against a hostile force in the Republic of Vietnam. During the period January 1970 to January 1971, he consistently manifested exemplary professionalism and initiative in obtaining outstanding results. His rapid assessment and solution of numerous problems inherent in a combat environment greatly enhanced the allied effectiveness against a determined and aggressive enemy. Despite many adversities, he invariably performed his duties in a resolute and efficient manner. Energetically applying his sound judgment and extensive knowledge, he has contributed materially to the successful accomplishment of the United States mission in the Republic of Vietnam. His loyalty, diligence, and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Army and reflect great credit upon himself and the military service.

Joint Service Commendation Medal (JSCM)

Citation:

For exceptionally meritorious achievement while serving in support of Exercise AHUAS TARA II, Republic of Honduras, during the period 15 March 1984 to 30 June 1984. Captain Whitman’s performance of duty during the exercise was marked by a “can do” attitude and willingness to expend every effort to achieve superior results. His conscientious actions, diplomatic manner, and professionalism contributed immeasurably to the successful completion of this exercise. Captain Whitman’s exemplary performance of duty reflects great credit upon himself, Joint Task Force Eleven, the United States Army, and the Department of Defense.

Meritorious Service Medal (MSM)

Citation:

For exceptionally meritorious service while serving as Project Officer, Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Information Management, Fourth United States Army, Fort Sheridan, Illinois, during the period 1 October 1984 through 31 July 1987. Captain Whitman assumed the responsibility for preparing the Fourth United States Army Worldwide Military Communications and Control System (WWMCCS) computer installation. With undying enthusiasm, he drove the project from the onset despite numerous changes that encompassed high technology areas such as Top Secret data processing, electrical and constructive engineering, and telephone circuiting installations. Captain Whitman’s outstanding performance of duty reflects great credit upon him, his unit, and the United States Army.

Navy Meritorious Unit Commendation

For participation with the US Army Task Group 65.6 (Army Land Clearance Group) during the clearance of the Suez Canal, for the period 12 April 1974 to 22 July 1974.

Citation:

For meritorious service from 12 April 1974 to 22 July 1974 during clearance operations, NIMBUS MOON and NIMROD SPAR, and Residual Force operations in the Suez Canal area, Arab Republic of Egypt. Operating with high international visibility under the tension of an uneasy truce and in the face of substandard living and working conditions, the personnel of Task Group 65.6 carried out their difficult and challenging mission with outstanding skill and dedication. After the Task Group provided intensive training and instruction to the Arab Republic of Egypt’s Army officers on the tools and techniques of minefield clearances, there was a tremendous increase in the capabilities of the Egyptian Army to locate foreign ordnance, identify it, and render it safe. As a result of this superb effort and in cooperation with the forces of the Arab Republic of Egypt and other participating nations, assigned explosive ordnance disposal and salvage operations in the Suez Canal area were accomplished efficiently and expeditiously, contributing significantly toward the restoration of a vital waterway and maintenance of peace in a troubled area. By their courage, perseverance, and unfailing devotion to duty throughout this period, the officers and men of Task Group 65.6 reflect credit upon themselves and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

The most memorable thing was getting a Christmas card from Anwar L. Sadat after meeting him during my service clearing landmines in Suez, Egypt. This man was just a regular farmer like myself, but was a great leader of the Egyptian people who only wanted peace between his country and Israel.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

While stationed at Fort Sheridan, IL, I was friends with SGM Kenneth Stumpf, a CMH recipient. He once called me a soldier’s soldier, and that was very meaningful to me.

Two other people who I greatly respect and admire were also at Fort Sheridan, IL, with me. They are LTC Lloyd D. McDaniels and COL Serge Demyanenko, both of whom I served with while in ARMR V and 4th Army.

Another is GEN Gary E. Luck (retired). He was an LTC while I was in the Advanced Engineer Officer course at Fort Belvoir, VA. I believe he was serving as an Infantry instructor, and I believe he was instrumental in getting me released from school to go to Egypt on Task Force 65.6 Nimbus Moon Land. Somehow, my name came down from the State Department as one of the Engineers to go on this assignment.

Another is GEN Colin Powell (retired), a COL in the 101st Airborne Division, while I was in the G3 section of the headquarters.

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

SGM Kenneth Stumpf, CMH recipient Fort Sheridan, IL. I would like to make contact with him. Good friends.

LTC Lloyd D. McDaniels and COL Serge Demyanenko at Fort Sheridan, IL. I have had some contact since I retired, but not now. Both are outstanding soldiers. Good friends.

GEN Gary E. Luck. Fort Belvoir, VA, Super Guy.

GEN Colin Powell. Fort Campbell, KY, Super Guy.

MAJ Overton Day (retired). Fort Belvoir, VA. I have been in contact with him, and he was one of the guys to get me to go on the Task Force 65.6 Nimbus Moon Land trip to Egypt. Good friends.

CPT Mike Nolan. Fort Campbell, KY. Served as company commander in the 326th Engineer Battalion, 101st Airborne Division. I have been in contact with him. Good friends.

CPT (Marine) Buck Thompson. Fort Belvoir, VA. We raised hell together. Good friends.

CPT Jack Stackhouse (deceased). Fort Belvoir, VA. We raised hell together. Good friends.

Can you recount a particular incident from your service, which may or may not have been funny at the time, but still makes you laugh?

I was sitting on the rocks alongside the Suez Canal talking on the radio to the Navy log birds (CH47) while the Egyptian engineers were getting ready to detonate some old landmines when the Engineer Battalion Doctor came up to me with a live Russian PMN anti-personnel mine in his hand with his thumb on the pressure plate and stuck it in my face. I dropped the radio handset and carefully grabbed the mine out of his hand. I removed the striker and gave the mine back to the Doctor. It was not funny at the time, but I look back on it as amusing now, because I could have lost my head if he had put a pound of pressure on the pressure plate with his thumb and detonated the mine.

While in Ranger school during the FL phase, our unit attacked an enemy unit located in the swamp during a night operation. The guy who was supposed to carry the M60 machine gun was hurt in my squad, so I volunteered to take it for him. The guy whose turn it was to carry the PRC 25 radio was hurt, so I also volunteered to carry it. We were maneuvering in water up to our chest or higher, and I kept getting tripped up by the tree roots underwater and would fall down completely submerged underwater. I could not get up by myself with the weight of the radio, the weight of the M60, and my own rucksack. The guy behind me would see my hat disappear, or he would run into the M60, which I managed to hold up in the air, and he would help me get up on my feet again. This happened several times that night. All the time, an NCO Ranger Cadre was walking close to me, watching me. Each time I would get up and just keep smiling as I continued to move forward with our mission. Later at graduation, that NCO came up to me and saluted me, saying how he had seen me go under several times and get up with a smile on my face, continuing with the mission. I never thought much about the difficulty until he mentioned it and saluted me.

I look back on it as a funny incident.

What profession did you follow after your military service and what are you doing now? if you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

After retirement, I went to work in a manufacturing company as a manager. I worked my way up to a senior management position before the Company had serious problems with the owners, and I moved on. I did some consulting work for a while, then began teaching at a local college, where I continue to teach today as an adjunct professor. I teach both management and marketing courses. When I went to college before going into the Army, I planned to become a teacher. Go figure!

What military associations are you a member of, if any? what specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

MOAA NH Chapter. Get no benefits. I was the PAO for a couple of years, and I enjoyed doing it and enjoyed attending the events and meeting other Vets.

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

My parents taught me to endure hardships and continue on. Being part Indian, I was taught to “endeavor to preserve.” We were very poor dairy farmers on a small farm in Massachusetts. We had to work hard for our living, but we managed with what we had. That training continued as I served my career in the Army. My focus is never to give up and make do with what you have. This is somewhat of a problem because I hold on to things too long (according to my current wife, the 5th one). I was taught to persevere even when things got tough. When things get rough, it is, “take two aspirin and drive on Ranger.” My experiences in the Army have caused me to continue with that attitude and behavior. I just drive on regardless of the difficulties. I think all the time positively.

When a difficulty presents itself, I always think of what can be done to get beyond it or get through it. I do not dwell on negative things. I once had a girlfriend that was always negative, and that relationship ended quickly.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Army?

Relax and enjoy your time in the military. Nobody can or will ever be able to take your experiences away from you. Cherish those experiences. Keep your head down when the lead is flying. Always do the right thing. Always tell the truth even if it hurts or your boss doesn’t like to hear it. Keep your chin up and always look on the bright side of difficulties. Always strive to be better. Get more education. Be happy with what you have and strive to be better.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with.

This has been a good trip down memory lane. Maybe someday I will write a book about my life and career in the Army.

I wrote the book:

Title: 3 days and 20 years; An Army Career

Kent Whitman

CPT US Army Retired

Corps of Engineers

Ranger

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

I enjoyed your story CPT Whitman, Spec 4 Roach draftee 70-72

Excellent rendering of a true patriot’s service to his country. Sorry you were screwed by a ring knocker.

Great stories Kent, I retired in 1988. Give me a call 6093351612. I was your neighbor on Tower Rd, Ft Belvoir and worked for the Engineer School.

Great work on your career.

Wow Captain Whitman, I knew you had some interesting prior assignments before we served at the USACE New England Division but thanks for doing this amazing writeup. My own army career was more than satisfying but maybe somewhat humdrum compared to the ride that you had! You are appreciated as having been a good mentor to me during my first active duty tour at NED1979-81. Best wishes!