By 1944 the tide of battle in World War II was turning in favor of Allied forces across the various theatres. With momentum building in Europe and the Mediterranean through the successive invasions of North Africa in November 1942 (Operation Torch), the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 (Operation Husky), and the invasion of Italy in September 1943 (Operation Avalanche) a much broader front was necessary to redirect Axis forces and free Russian troops. A keystone to accomplishing this was debuted by US forces in 1942 and would prove invaluable in spearheading further ground combat operations, the parachute infantry. Though the US was late in establishing airborne capability it would quickly become the centerpiece of Operation Overlord, the assault of Western Europe on June 6th, 1944. And one fledgling unit in particular would prove the most audacious of US airborne troops leading this invasion, the 1st Demolition Platoon, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR). Trained as demolition saboteurs to destroy enemy targets behind the lines this unit was commonly known as the Filthy Thirteen and became the real-life inspiration for the book and 1967 movie, The Dirty Dozen.

1st Demolition Platoon, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) Was Commonly Known As the Filthy Thirteen

In reality, the Filthy Thirteen are well known to anyone that has seen images of the paratroopers readying for D-Day with Native American haircuts and war paint. The inspiration for this came from Jake McNiece, who was part Choctaw and unofficial leader of this unwashed, hard-charging demolitions outfit, making these men the most recognizable airborne troops of all time.

Coined by War Correspondent Tom Hoge in an article for Stars and Stripes (June 1944) the name “Filthy Thirteen” referenced the practice, while training in England, of washing and shaving only once a week and never cleaning their uniforms. Of the activities of the Filthy Thirteen, Jack Agnew once said, “We weren’t murderers or anything, we just didn’t do everything we were supposed to do in some ways and did a whole lot more than they wanted us to do in other ways. We were always in trouble.” Unlike the Dirty Dozen, the Filthy Thirteen were not convicts; however, they were men prone to drinking and fighting with serious disrespect of officers, spending considerable time in the stockade. In one example only weeks before deploying, Jake McNiece blew up part of their barracks, stole a train while drunk in town and drove it back to base.

The legend of The Filthy Thirteen got its start at Camp Toccoa, Georgia during their training with the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment as part of the Regimental Headquarters Company. This experience, the leadership and ensuing preparations for war created a unique culture across the men, who just like airborne troops still today, were all volunteers. Activated in July 1942 the 506th undertook one of the toughest physical training programs in the Army including twelve-hours of daily strength and endurance training, runs to the top of Currahee Mountain (three miles up and three miles down), and forced nighttime marches. Said one member, the training was intended to “acquaint you with a well of energy which you had never tapped in your life before.” Here, the men also endured what was reported to be the toughest obstacle course in the United States Army, part of “A” Stage training and a primer for jump school.

In late November 1942, with the “A” Stage training behind them, the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment was ordered to Fort Benning for parachute training. 3rd Battalion, with the 1st Demolition Platoon in tow, traveled to Atlanta by rail and then marched the remaining 136 miles to set a new, endurance march world record previously held by the Japanese Army. On the heels of this accomplishment the men completed their parachute training and qualifying jumps to receive the Parachutist Badge. The 506th then moved to Camp Mackall, North Carolina, where extensive tactical training was conducted, centered on night jumps with full combat equipment. In early June 1943, the Regiment was attached to the 101st Airborne Division and moved west to participate in the Tennessee maneuvers. Here they dropped behind the lines to establish roadblocks, destroy bridges, and snarl communications, after which the 506th moved to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, arriving as a fully trained fighting unit. At Fort Bragg, the 506th largely participated in reviews for visiting dignitaries, including the British Foreign Minister, Sir Anthony Eden.

Unit Played Critical Roles in Preparatory Operations for D-Day

During August 1943, the unit reported to Camp Shanks, New York, to prepare for overseas transport. The 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment crossed the Atlantic on the SS Samaria, arriving at Liverpool, England, on 15 September 1943. While in England the 506th was stationed in Wiltshire County and villages such as Aldbourne, Ramsbury, Froxfield, and Chilton-Foliat, with each man mastering the tasks necessary to make the unit run smoothly in combat.

Perhaps little known by most, here the unit also played critical roles in preparatory operations for D-Day, Operations Wadham and Rankin. Wadham was one of three diversionary operations (Starkey, Wadham and Tindall) comprising the overarching Operation Cockade. Executed during September 1943, planners for Operation Wadham wanted the Germans to believe the Americans would invade in the area of Brest, a seaport on the Breton peninsula. The notional order of battle for Operation Wadham involved two headquarters corps, seven infantry divisions, two armored divisions and the 101st Airborne.

Operation Rankin on the other hand was a very real undertaking, the details and existence of which were known only to a handful of officers. The purpose of Rankin was to plan for a German surrender before the invasion in Normandy, a possibility due either to a military disaster on the Russian front, to an internal collapse of Germany, or both. The 101st Airborne was to play the key role in a rapid airborne invasion and seizure of German held territories, but without trigger conditions the operation did not take place.

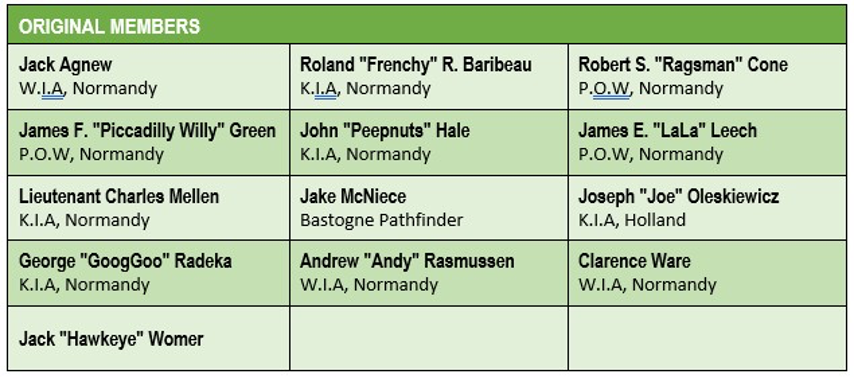

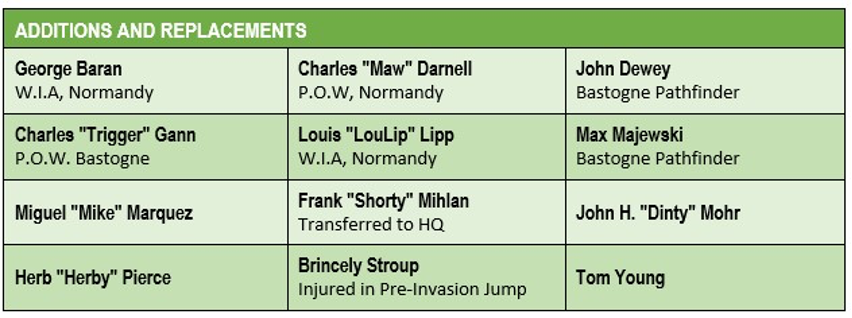

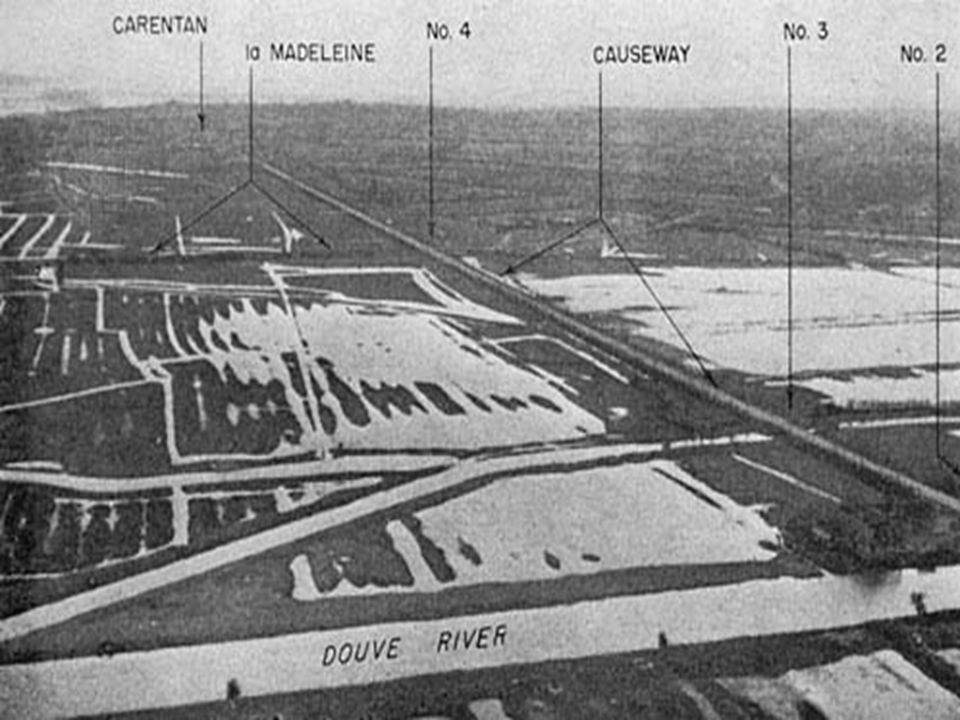

On June 5, 1944, the men of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment parked by the aircraft that were to carry them into their first combat mission. As demolition-saboteurs the 1st Demolition Platoon’s mission was to defend or destroy two bridges over Douve Canal, preventing the Germans from reinforcing the Utah and Omaha beachheads. Located near the small Normandy village of Brevands the mission was considered suicidal. Nonetheless, the men accomplished their objectives despite a vastly superior enemy force and repeated German counter attacks, holding until relieved on June 10th. One battle at the Canal reportedly pitted thirty paratroopers against an entire German Battalion. In doing so, half of the men were killed, wounded, or captured either during the jump or in combat soon afterward. Jack Womer fought his way out of the swamp that he and forty other paratroopers landed in but proved to be the sole survivor. On the second day, Jack participated in fighting that resulted in the capture of over one-hundred Germans of the 6th Paratrooper Regiment, only to see them annihilated by the German’s own mortar barrage.

The men fought bravely for thirty-six days in Normandy before returning to England for resupply and redeployment, contributing to the liberation of the first major city in France, Carentan, and earning the 506th a unit citation, “In the face of determined and fierce enemy resistance, the unit seized and kept open the main causeway leading to the beaches. This action led to the successful and rapid advance inland of the seaborne forces and insured the establishment of the beach-head in Western Europe.”

Second Combat Jump of 1st Demolition Platoon, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment

The Demolition Platoon’s second combat jump would come quickly on September 17th as part of Operation Market Garden along with the rest of the 101st and 82nd Airborne. The objective was to create a salient into German territory through the Netherlands with a bridgehead over the River Rhine, creating an Allied invasion route into northern Germany. This was to be achieved by seizing nine bridges along Highway 69, later named Hell’s Highway, with combined U.S. and British airborne (Market) followed by land forces (Garden). Fighting for seventy-eight consecutive days the Allies fought to keep this vital transportation corridor open. The 1stDemolition Platoon specifically was assigned to defend four bridges over the Dommel River in Eindhoven, the Netherlands. Taken without a fight, the 506th formed a defensive perimeter around the bridges though German bombing of the city again killed or wounded half the men in the Demolition Platoon. Reportedly, the remaining Filthy Thirteen then fought their way through tanks and infantry, removing German explosives from bridges, improvising and always pushing forward. McNiece acquired an abandoned German truck and drove his men into town. There, the men dodged 88mm rounds and fought house to house until victorious. For the rest of the campaign, the demolitions men secured the regimental command post, protected wire-laying details, and in one case were assigned as a rifle squad to an understrength company.

Coming back AWOL from Paris after Market Garden Jake McNiece volunteered for the Pathfinders with Jack Agnew, paratroopers sent in ahead of the main force to guide airborne and resupply drops. Half the surviving members of the Filthy Thirteen followed him into the Pathfinders expecting to sit out the rest of the war training in England. But no one could foresee Operation Autumn Mist in December 1944, later known as the Battle of the Bulge. To assist in relief of the 101st Airborne the Pathfinders were dropped into Bastogne at the height of the fighting, McNiece securing a position within eyesight of the Nazis. Surprisingly, with expected casualties of eighty to ninety percent, the twenty pathfinders lost only one man.

In many ways Operation Market Garden failed to achieve its objectives and in Spring 1945 a Rhine River crossing into Northern Germany was needed. For this purpose, Operation Varsity was launched on March 24th, 1945. Involving more than 16,000 paratroopers and several thousand aircraft Varsity was the largest airborne operation in history, meant to help the surface river assault by landing two airborne divisions on the eastern bank of the Rhine near the town of Wesel. Once again, Jake McNiece volunteered as an observer for the 17th Airborne Division to extend his combat jump career.

At the closing of the war, the Demolition Platoon deployed to the Alps, where they were ambushed by mortar fire. Armed with only a knife, a pistol and two grenades, Jack Womer scaled the mountainside to coordinate a fire mission that killed eight Nazis and saved the unit. Occurring the day after the war in Europe officially ended, this was the final patrol for the Filthy Thirteen and a fitting end to their exploits. In retrospect, their deeds have lived on beyond them and will remain larger than life. War Correspondent Tom Hoge wrote “They called themselves the ‘Filthy Thirteen,’ and took pride in the reputation they had of being the orneriest, meanest group of paratroopers who ever hit their base.” According to Barbara Maloney, daughter of Jack Agnew, “Most of the men that I talked to that were with the Filthy Thirteen — they wanted to be with that group for a number of reasons. One is they felt safe with them. They trusted them. The 506th … a lot of these guys, that’s their identity for a lifetime. They were young men defining themselves. That’s who they are the rest of their life.”

For the 69th anniversary of D-Day, Jack Womer was decorated with the French Legion of Honor in Carentan.

Airborne All The Way!