PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

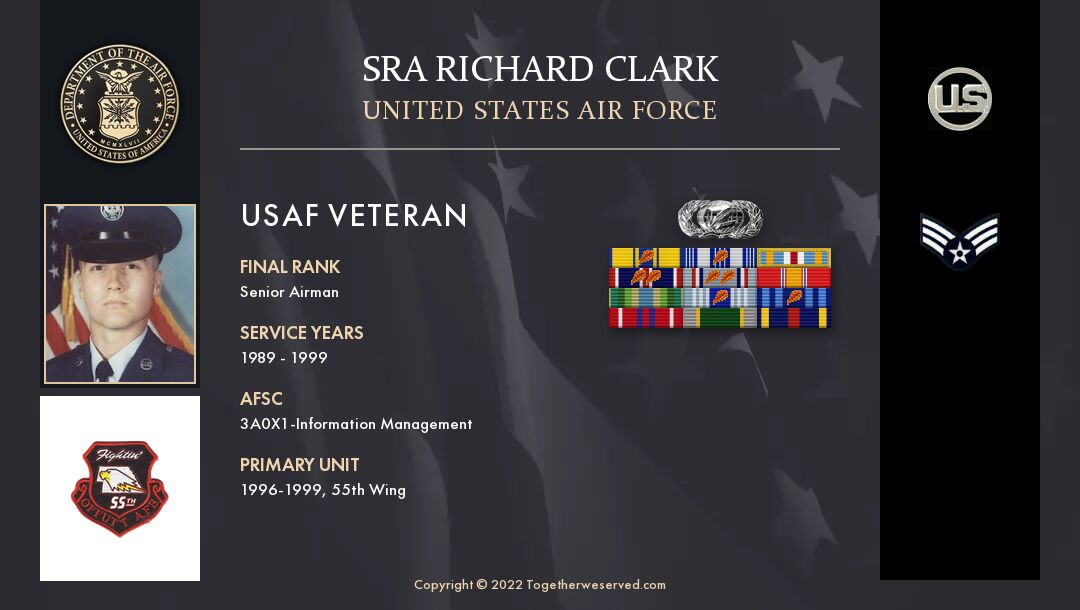

The following Reflections represents SrA Richard Clark’s legacy of his military service from 1989 to 1999. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Air Force.

My father was a United States Marine, so I grew up on stories of commitment and duty. I knew some of the hardships he had faced in Viet Nam, and at the time, we had no idea that Agent Orange was killing him. He was medically discharged at ten years due to incorrectly diagnosed “pinched nerves” that were, in fact, two ruptured discs in his lower back, even with all of the medical mix-ups my father deeply loved and missed the Corps.

Several of my uncles (2 – 4 years active with the rest of their time in the Army Reserves) had joined the Army, and they discouraged me from doing the same. Compared to my father’s stories of time spend in-country chasing tunnel rats (a cave-in trapped him in a pocket of the tunnel, but they had dug him out before his air ran out, after that he became horribly claustrophobic) made their stories of time in the field never seem as bad as they tried to convey. Nobody in my family ever cared for the open water, so the Navy was out…honestly, it was not considered. OK, briefly when Top Gun came out, but never seriously. Besides, I never like riding motorcycles, and they appeared to be a requirement.

The consensus was that peacetime duty would best be done in the United States Air Force. They had the ‘best bases, best chow halls,’ which ended up being true in my experience. In the fall of 1988, I took my ASVAB and scored high enough “for anything.” It seemed unusual that my recruiters’ eyes got so large, and he walked my scores around to the other services recruiters, but I guess I earned him bragging rights. I enrolled in the Delayed Enlistment Program, and was administered the Oath of Enlistment by a 1LT at the MEPS in Detroit, Michigan.

It turns out I got accepted at the University of Michigan in early 1989. My mother had talked me into applying just to ‘have options,’ and I was awarded a few low-dollar scholarships to boot – I suppose a 30 on your ACTs (with a 31 in Science) will get you somewhere. But I had just watched my brother scrape for four years to pay for his college, and I didn’t want to figure out how to pay for it all. After finishing 13 years of school, college even seemed to be anticlimactic at that point.

Finally, I decided to travel while serving my nation and felt the USAF would be the most beneficial. By my 17th summer, I’d already been to 48 of the 50 states, Canada and Mexico.

My family trips every summer between 1981 and 1987 were part of my father’s legacy to me. Rain falling in the Smoky Mountains near Gatlinburg, Tennessee. Going to Orlando, Florida, the year Epcot opened and eating at the World Showcase. Listening to The Reflex by Duran, Duran under the canopy of the Redwoods on my brother’s boombox in California. Watching a sailboat crash into the dock wall, only to have a guy come out and tell the owner he couldn’t put his boat in there in San Francisco. They were eating clam chowder at Pike Place Market in Seattle, Washington. Sitting in the same booth, Billy Joel and Christie Brinkley sat in on their honeymoon in Bar Harbor, Maine.

But Japan or Europe seemed out of reach without someone else paying for my airfare. Travel was in my blood. During the six years, I lived in Germany, and I got to over 20 countries. I still haven’t made it to Japan or Australia, though, nor Alaska or Hawaii for that matter.

So I decided to forego college, and when I finished my senior year of high school, I enlisted on 17 Jul 1989.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

Like every other former enlisted member here, after joining, I went to Lackland AFB, Texas. Looking back, the people I met there and the relationships I made were some of the most important ones of my life. BMTS (3706/598) introduced me to others from all over the country Goel Barbu, Urban Romero, Steve ‘Brown Ice’ Brown, Kole Hance, and Hargraves; these were great people. TSgt Ward and Sgt Lynch were great TIs.

I didn’t quite understand that Tech School drove basic training. Hence, it seemed unusual that so many of my flight mates ended up going to Keesler AFB, Biloxi, Mississippi (Goel Parbu went direct duty to Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona to be a combat photographer.) Still, my 6-week self-paced Tech School lasted a whopping nine days (including one day in the process, a weekend, and one day to out process). My proficiency advanced out of typing my first night and completed my first block of instruction that evening. On my first and only, Friday there we received our orders, and I was pleased that both Kole and Brown Ice were going to Offutt AFB, Nebraska too. Romero got an assignment to Colorado, and Hargraves, from deep-woods Louisiana, got Elmendorf AFB, Alaska…

“Hey, guys. Is this Arkansas?”

“No, Hargraves, AK is Alaska.”

“Alaska? I don’t even know where that is. Do they have hunting and fishing?”

“Yeah, Hargraves. You’ll be fine.”

I never was able to get that band back together.

When I arrived at Offutt AFB, Nebraska, I was met by Sgt Chalmer Bortz. Being assigned to the base side BITS was interesting, and another great crew of people to get to know…David “Jimmie” Hendrix, John Otto, Frank Gilroy, Betty Jo Narveson. Going to Old Town to eat at Spaghetti Works, walking around the three malls in the area, or drinking in the dorms were the ‘fun’ things we did. After a few months in Omaha, I knew that my service would end after four years if I didn’t get overseas.

Kole and Brown Ice had come to Offutt as well. Kole was put in Logistics in an inside office of Building D, with no windows, checking material into and out of a classified safe, and running to the Comms Group twice a day to send and pick up messages. Brown Ice was up at SAC Headquarters (later-STRATCOM in 1992) BITS when he found out the Chief’s name who controlled the Postal assignments. Chief Derrickson in the Pentagon answered that phone with:

“What?” Not angry, just busy.

“I’m calling from Offutt AFB. I was given your name about special duty postal assignments.”

“Name, Social.”

“”

“Is your base preference list up to date?” I already had changed my preferences based on Brown Ice’s advice, and he’d called him the week before.

“Yes, Chief. That’s all set.”

“Look for your orders.”

True to his words, my orders hit the office four weeks later to sunny Zweibrucken Special Duty Postal. In October 1990, I received word I was being diverted to Ramstein Air Base, Germany. Apparently, Zweibrucken was being closed and returned to the German Government, Ramstein Ho!

I arrived on 4 November 1990 and was folded into the controlled chaos that was the largest military post office outside of the Pentagon. I don’t recall the mail numbers, weights, or pieces processed. But those numbers tripled after the Gulf War kicked off. Ramstein Air Base and the Landstuhl Army Regional Medical Center had an influx of 4000 active duty and reservists: filling every mailbox on Ramstein. For some reason, all they did was mail order shop. At the start of the war, we processed a 3/4 full 40 ft SeaLand bulk mail container. A year later, we were emptying 4 or 5 a week. Most of the reservists were gone by this point, so we manually destroyed thousands of pounds of catalogs and other types of bulk mail.

As it turned out, Brown Ice had gotten diverted there as well. I also met Shane Stults and a few others. I ended up getting IPCOTs to spend six years at Ramstein.

I was okay with leaving that AFSC and returning to 3A0 in the fall of 1993, moving to be the 86th OSS Weapons and Tactics Flight admin. Maj Hibbs (Lt Col by the time I PCSd in 1996), William “Ed” Cox, Jackie Tuscynski, Tammie and Tammy (The Tammys), Kristie, Dorothy Lillie, Bob Luedtke, Mike Hauter, Mike Witt, and Kerry Jacobsen, to name just a few. What a great bunch of friends.

Following the accident investigation of the crash of the CT-43 carrying Commerce Secretary Ron Brown, I had a really difficult, challenging time getting the things I’d seen out of my head. The sights, sounds, and smells made it harder and harder to fly and be a productive member of the air force I loved, and I completed my service commitment after ten years and moved on.

I didn’t realize how much the trauma I’d experienced in Croatia, and it changed me. I regret leaving the service. I didn’t know how to ask for help.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

On 3 April 1996 at approximately 08:52 EST (2:52 CET), the United States Air Force (USAF) CT-43, the military version of a Boeing 737-200, crashed into a hillside 1.6 miles northeast of the Dubrovnik airport in Croatia. I was unaware of this until later that same evening while sitting in the chow hall, and I saw a twisted aircraft fuselage being shown on CNN International. The caption read something about Ramstein Air Base and Commerce Secretary Ron Brown. I remember saying out loud, “Is that one of our planes?” An Airman at the following table, sitting with a co-worker or buddy, replied, “That’s our Nightingale.” As if on cue Mark Clark a GS-4 who worked in Weapons and Tactics, came in. It was strange to see a civilian enter the enlisted mess. He glanced up at the TV before his eyes started to scan the room. As he looked around, our eyes met. The room quieted as he walked over to where I was sitting and said, “Well, I don’t have to tell you what happened. General Abrahams wants you to provide support to the team going in the morning.”

I had been augmenting the Command Post since December. That involved tracking humanitarian C-130 flights and airdrops into Bosnia-Herzegovina, Yugoslavia, and Croatia; distinguished visitor flights, including Hillary and Chelsea Clinton’s visit to Bosnia in March 1996, she flew on the same aircraft that crashed. I had gotten familiar with the Wing Command staff, and I felt proud to be selected to support this mission. The next several hours, I coordinated the creation of TDY orders and aided the activation of a deployment line. Part of that the next morning was a medical review for all deploying personnel.

I had just returned from having the orders signed by the personnel flight, and I was met my barely controlled chaos. The med flight was there reviewing shot records and administering immunizations. People were packing equipment, and others were marshaling travel bags and arranging for transportation to the flight line. I was informed by a nurse that I needed a yellow fever shot, and she apologized that they had just come out of the freezer. The shot felt like liquid metal, so cold it felt hot, as my whole shoulder seemed to go numb and burst into flames simultaneously. I informed the med staff of that and mentioned that I might be going down. They quickly cleared a spot on the floor, apologizing to me as I laid there that the immunization was just too cold.

People came in requesting orders and other information, and I directed the chaos from my special spot on the floor. No, those are in the red folder. No, sir, that is a blue folder; please put that back and take the red folder. Yes, that. No social security numbers and deploying personnel roster are in the lime green folder; please show me…yes, that is it. Eventually. The nausea and roaring in my ears passed, and I got up and took over from there. That is when I saw the vice wing commander standing next to my commander, and he said, “That’s why he’s going.”

I climbed off the bus onto the Ramstein flight line and watched as loadmasters packed and palletized everything we were taking before loading it onto the C-130. We loaded onto the bird and were strapped into flight seats along the aircraft’s fuselage in harnesses. I was talking to the crew chief, and he said I did not look very good. When I explained the yellow fever shot, he offered to strap me into cargo netting. He laughed at the look that had to have passed over my face and said that way I could sleep suspended. I took his advice, and most of the flight over Germany and Austria, I was cocooned in the netting.

I was jolted awake by a boom of thunder and turbulence that had the plane lurching and dropping, climbing to start the coaster ride again. More lightning flashed outside the windows as I disengaged myself from the netting, and a boom so close that it matched the flash outside made it through my foam hearing protection. The crew chief floated past me in bounding leaps (basically free-falling inside a dive) to look out a window. His declaration that there was no fire did not ease my mind as we banked right and turned on a dime. After some consultations with the flight crew, he informed us that we were diverting to Ancona.

As I stood on the tarmac in Ancona, Italy, regional airport., the scorches mark on the number 3 engine and damage to the propeller was sobering. Less than 20 hours had passed since IFOR-021 (the designation for the flight) had disappeared from the radar screens of Zagreb Air Traffic Control and a USAF Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS), and here we were. I watched as the ground crews refueled the two MH-53 Pave Low Helicopters to transport us into Croatia. We had departed Ramstein Air Base, Germany, six hours before on a perfectly sound C-130 Hercules transport aircraft. The helicopters, who were aiding in the recovery of the wreckage, made the hour and a half flight to Italy to pick us up.

An hour later, we were flying back into the storm along the exact same air corridor. I was sitting next to the aerial gunner at the helicopter’s tail when the pilot signaled weapons and countermeasure test. A stark reminder that we were flying into a former war zone as chaff and flares began popping out of the helicopter, like water from a shaking dog after a bath, drifting lazily to the Adriatic Sea a few hundred feet below. The gunner next to me squeezed the trigger of his minigun, and I watched the sea chopped into frothy bits behind us; the sound reminded me of twisting bubble wrap packing, “Brapp, brapp.” I made a motion to catch his eye and worded, “How many.” “About 200 rounds,” came his worded reply.

A bit later, we were on approach flying low over burned-out villages and shattered houses. It had only been a couple of months since Serbian forces had finished pulling out of the area, and some people still felt uncomfortable moving around in broad daylight. Others waved at us, then got back inside out of the rain.

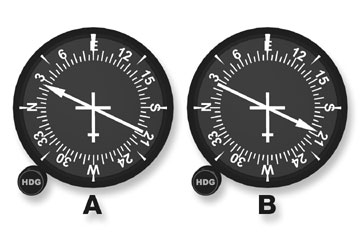

The Lieutenant (I really wish I could remember his name) on my left tapped my shoulder and yelled that we were 20 minutes out and just flown over the KLP non-directional radio beacon (NDB). An NDB is a simple navaid that is used extensively in the Third World. An aircraft is usually equipped with two automatic direction finders (ADFs). By setting an ADF to the proper frequency of an NDB, you can determine if you are off course and glean certain threshold points in flight. Having two ADFs allows you to set both the last beacon and the next beacon on your flight path. But IFOR-021 did not have two since the CT-43 was used as a “trainer” aircraft (the T designator in CT-43). It was only equipped with a single ADF.

It was later determined that the pilot of IFOR-021 had left his sole ADF set to the KLP NDB. At that moment, I only knew it was raining heavily. Depending on which version of the crash accounts you may read, it was either raining moderately or the worst storm locals had seen in years when the flight went down. Regardless, I got very wet running to the shelter of an aircraft hangar after exiting the helicopter.

Our stay was at the Hotel Croatia in Cavtat, Croatia, a 4-star establishment that was only 4 miles from the airport. They were attempting to reopen after having been closed for over two years during the war. When they heard our team was coming in to investigate the crash, they opened their doors to us to use as a base of operations. Our Mishap Board team’s officer was Colonel John E. Mazurowski, the 86th Operations Group Commander. He was the boss, of the boss, of the pilot that crashed and had come down to find out what had happened to his people.

Less than an hour after our arrival, an Army major had arrived to brief our team and escort us back to the airport to where the recovered bodies were being stored. The morgue, as designated, was nothing more than an aircraft hangar with portable, industrial air conditioners. When we arrived, there were only 20 or so bodies of the 35 present. There is no description for it, twenty-five years have passed, and the closest I can come to describing the smell is to burn a pound of bacon to a smoky crisp and then throw on a hand full of hair on the burner. On second thought, do not. You are better off not doing that. The first week on the trip, my roommate was the photographer responsible for all the pictures taken of the crash site and the morgue. He shrugged off questions about his state of mind, but I heard him cry in his sleep several times while we were in Croatia.

My first of dozens of flights up the mountain was with a team of civil engineers we had flown down with, and they were surveying and plotting the location of each piece of debris recovered from the mountain. The intact tail section of the airplane sat on the hillside, from it was pulled the only surviving member of the aircrew. Technical Sergeant Cheryl Turnage had survived the crash by several hours but tragically died from her injuries while on the way to the hospital.

I assisted in loading body bags for the return of the same flight with a group of US Army personnel that had spent the day recovering body parts. They had each been given boxes of resealable baggies and disposable cameras. Their instructions had been simple; they were told to photograph each piece they found, put each part in a separate bag, and mark the grid coordinates of each part on the baggies with a permanent marker. That was the most somber group of people I have ever seen.

That night Col. Mazurowski and our team sat around a table in one of the hotel’s conferences rooms. We were on a conference call with Brigadier General William E. Stevens, Commander, 86th Airlift Wing, at Ramstein Air Base. Brig. Gen. Stevens informed Col. Mazurowski that Major General Charles Coolidge, Jr., was being relieved in the morning as the Mishap Board had been changed to a formal Accident Investigation Board. His tone of voice left no doubt in the room that at least some of the focus into the crash had shifted to include the colonel. The four most senior officers in the room were to leave as well. Ultimately, they had collected information that was later used in their own punishment.

Maj. The following day, April 5th, with National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators and aircraft engineers from Boeing. Among them was an NTSB investigator, Thomas Haueter, who had overseen a “19-month probe into the unexplained crash of a USAir Boeing 737-300 near Pittsburg in September 1994.” In discussions with him later, l learned that he had just completed the above investigation when the NTSB Chairman called him at home to put him on the plane to Croatia. Weeks later, on May 11, 1996, he would be in the Florida Everglades investigating the crash of ValuJet Flight 592, a DC-9 flying from Miami to Atlanta, killing all 110 people on board.

With the help of our translator, a very nice, dark-haired Croatian lady, we began to question locals about what they had seen and heard. I sat in on more than a dozen of these sessions, but the only one makes me tear up when I think about it. The person being questioned was a police officer from Dubrovnik. He had been on the job for less than two weeks when he and his partner responded to the crash site. They had happened upon the tail section of the aircraft quite quickly. Given its size, it stood out, and they had found TSgt Turnage.

He had determined that she was dead, and they had continued their search for survivors. About an hour later, they were passing back by the tail section when they heard moans. TSgt Turnage was still alive, and they extracted her from the wreckage and attempted to get her medical attention. She died on the way. You could see the overwhelming guilt and sadness on his face. You could almost hear the what-ifs in his voice. He was just 20 years old, a little younger than me at the time, and I was 24.

On April 6th, one of the locals called, asking if he would be needed again. He wanted to make sure nothing else would be required, and he was eager to ensure we did not have any more questions. I had sat in on his first interview, and he was the person who was responsible for the maintenance and operations of the NDB equipment at the airport. I never knew his name until I was researching in the mid-2000s. Niko Jerkic was found hanging in his barn later that morning. The translator stated that his suicide note mentioned that Serbian Army personnel had removed more modern navigation equipment from the airport when they had left. He felt responsible for the basic NDB and was sure that it had led to the crash. He took his own life, and sadly it was determined that the Dubrovnik NDB was in no way related to the crash.

I returned to Ramstein Air Base a few weeks later. It would be another two months before the results of the accident investigation were known. It was determined that the plane should have never attempted to fly into that airfield. They lacked the proper equipment to land there in good weather, and the field had not been surveyed nor approved for US Air Force planes to land there in the first place. The pilot had made several planning errors that caused him to arrive late, fly too fast, and be rushed to the destination.

As for the last point, Captain Davis and Schafer flew from the KLP NDB toward the Dubrovnik airport 9 degrees left of his intended course. They hit the mountain a mile short of where they would have started looking for the runway.

In all, the Air Force punished 16 officers related to the crash. Both Brig. Gen. William E. Stevens and Col. John E. Mazurowski received Article 15 (non-judicial) Punishments for Dereliction of Duty. The rest of the disciplinary actions ranged from Letters of Reprimand to verbal counseling.

Brig. Gen. Stevens was reassigned as Assistant Deputy Undersecretary of the Air Force and an air attache in Africa. He retired on September 1, 1998. On January 6, 2003, he died of colon cancer in Fairfax County, VA, and was 54 years old. Col. Mazurowski retired in November 1996, I last saw him at a going-away party in June of 1996, and he seemed to have aged ten years.

Anyway, that is the cold factual retelling.

I always downplayed my role and what I experienced there. I was just there providing administrative support to the accident investigation team after all. Two days after the crash, the storm that had been soaking the area (and had been a contributing factor in the crash) had passed, and the weather was gorgeous for the rest of my time in Croatia. What could I possibly have to say about ‘me’ that matters more than the lives lost?

Let me be frank…I lied to so many people for years. To most, if I told them anything, it was that I had been in a hotel for several weeks, no biggie. To be honest, I cannot remember who I had told what version of my days there too. I think my father suspected more happened. He looked at me hard the next time I saw him in late May of 1996 and pulled me aside. He told me that I had a look he had seen on the faces of his fellow Marines in Viet Nam. He died of ALS in January 1997.

People that were concerned about me, I could see it in their faces. I downplayed every part of my time there and made it no big deal. I told people I was fine, but wow my roommate, was the combat photographer that had to photograph each ‘single’ thing related to the crash. He cried at night until he would fall asleep exhausted. He left after three days.

When he returned to Ramstein, they sent him back with a box full of film to re-shoot everything because some people had expressed concern that the digital camera images could be manipulated. They wanted to ‘not’ have those questions ever come up. He was not in my room the second part of his trip. But he, he was someone you could feel sorry for.

I had told some people that I never went up on the mountainside. That I never entered the hangar. That I did not really have much to do, I wish I had not. The first few days were brutal and sad. Moving a piece of wreckage and finding the hand of a man lying in the grass. Who had last held that hand; a parent, lover, wife, child, and never would again.

Helping to remove the pilot from his chair in the cramped, shattered cockpit and slowly extracting his crushed body from the gauges and dials, taking care not to change any of them, only to have his helmet come off in the flight surgeon’s hands with the top of his head still inside. That night he reminisced that he’d seen his family administer flu shots a few months before.

I think about those weeks spent every day. I think about the airfield manager, Niko Jerkic, that was interviewed. He spoke slowly and deliberately during his debrief. The retreating Serbian Army had taken most of his equipment, and while a new ILS had arrived, it had not been installed in time to help the plane. I remember when the Croatian Police came to tell us of his death, the translator translated in a clear voice with tears running down her cheeks. The note he left said he alone was responsible for the crash. Because the Serbian Army stole his equipment…

Still, the nightmares returned in the summer of 2019; trauma feeds trauma.

The dreams, there are a few, but I have two stand-out ones.

First, I am walking through the cold aircraft hangar. Tarps and tables covered in bags containing individual body parts, each labeled with where it (the part of he or her) had been recovered. Things that you would recognize as people are covered in towels.

I do not think I smell it in the dream, but I certainly remember the smells clearly, knowing precisely what everything smells like. The only sound I can remember is of sea birds crying out as they fly over the airport. I know, in all honesty, I probably could not have heard them because the aircraft air conditioners are all running outside the building. Flexible air ducts run along the floor like giant snakes, blowing cold air out.

Sometimes I wake up with my teeth chattering.

The other dream is the mountainside. I am always standing next to the boulder that the wing hit. The shear line from the impact is fresh. There are abundant sunlight and blue, clear skies, and US Army infantry soldiers (they found the crash site) are standing around the hillside with hundreds of little flags (sometimes tiny red cones) that marked the location of the bagged body and aircraft parts. Nobody is moving…everyone is just standing as if waiting. The tail section is down the hillside over there, and the wind is blowing, and the sea birds cry out as they ride on the air in from the Adriatic Sea. I usually wake up with my pillow wet from tears.

Other actual memories were not so bad too:

I am standing in the hangar door, not the giant doors of the hangar that stayed closed to keep the cold in. Just a regular-sized door in the side; the rain was still pounding down, and the wind was blowing…I was facing the runway. There was a building to our left, and we called it the fishbowl, where the press could be. Cameras were set up, but nobody was after that. We arrived on 4 April there was not much more for them to see. But they diligently reported for a while (the New York Time Frankfurt Bureau Chief was among the dead after all); then they mostly packed up and went back to wherever they were from…

Anyway, it was still early, and the wind was blowing, and the rain was pouring down, and just like that, it stopped, and the clouds broke overhead. Shafts of sunlight fell like stage lights all over the airport grounds. A rainbow appeared in the east, and the smell of jet fuel exhaust and wet tarmac filled my nose.

Another, I am in a rental car with a TSgt from logistics or finance, the 1st Lieutenant who was driving, and one of the translators we hired from Dubrovnik. We are driving to the city to procure/rent copier machines or printers (the little things you do not think to bring). We are driving along highway 8, passing burned buildings and farms (remember the Bosnian/Serb war had just ended. It was why the trade delegation flew there, to begin with). Anyway, we come around this bend in the road, and the lieutenant unexpectedly pulls across the highway and breaks heavily to a stop. He throws it in park, hops out of the car, and excitedly says, “Oh, come on, guys!” I jumped out of the car and realized what he was so excited about old Dubrovnik City.

I have pictures and film footage from the Associated Press pool that show the people’s faces and far-off shots of me unloading body bags from the helicopters, our translator, and the Croatian Army liaison. (Side note: I was watching Game of Thrones, and the first scene of Kings Landing where they are standing on the walls with the sea in the background made my stomach twist…I had stood on that wall).

To end this on a high note, the front desk receptionist was a badass. We talked once over drinks and fresh seafood when I ran into her in the village of Cavtat, and she told me about how she had hidden children in her barn from the Serbian Army so they wouldn’t be killed during the ethnic cleansing. She had hung freshly washed bras and panties on the drying lines to deter the soldiers from entering the barn. Apparently, they were just murderers, not rapists or particularly lecherous.

The five crew were my fellow airmen from the 76th Airlift Squadron, 86th Wing, Ramstein Air Base, Germany. Captain Ashley Davis, pilot, Captain Tim Schafer, pilot, Staff Sergeant Gerald Aldrich, flight mechanic, Staff Sergeant Robert Farrington Jr., steward, Sergeant Cheryl Turnage, steward, and Technical Sergeant Shelly Kelly, steward.

ALDRICH, Staff Sgt. Gerald, flight mechanic

ANTONINI, Niksa, photographer

BEBEK, Dragica Lendic, interpreter

BROWN, Ronald H., Secretary of Commerce; Washington

CHRISTIAN, Duane, security officer, Commerce Department

CONRAD, Barry L., chairman, Barrington Corporation; Coral Gables, Fla

CUSHMAN, Paul, executive vice president, Riggs National Bank; Washington

DARLING, Adam N., confidential assistant, Commerce Department

DAVIS, Capt. Ashley, pilot

DOBERT, Gail E., deputy director, Office of Business Liaison, Commerce Department

DONOVAN, Robert E., president, ABB Inc.; Fairfield, Conn

ELIA, Claudio, chairman, Air & Water Technologies; Greenwich, Conn

FARRINGTON, Staff Sgt. Robert Jr., steward

FORD, David L., president, Interguard Corporation; Luxembourg

HAMILTON, Carol L., press secretary, Commerce Department

HOFFMAN, Kathryn E., senior adviser for strategic scheduling and special initiatives, Commerce Department

JACKSON, Lee F., U.S. representative, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

KAMINSKI, Stephen C., commercial counselor for U.S. and foreign commercial service, Commerce Department

KELLOGG, Kathryn E., confidential assistant, Office of Business Liaison, Commerce Department

KELLY, Tech. Sgt. Shelly, steward

LEWEK, James M., analyst, Central Intelligence Agency

MAIER, Frank, president, Research International Corporation; Dallas

MEISSNER, Charles F., Assistant Secretary for International Trade, Commerce Department

MORTON, William, Deputy Assistant Secretary for International Economic Development, Commerce Department

MURPHY, Walter J., vice president, AT&T Submarine Systems Inc.; Fanwood, N.J.

NASH, Nathaniel C., Frankfurt bureau chief, The New York Times

PAYNE, Lawrence M., special assistant for U.S. and foreign commercial service, Commerce Department

PIERONI, Leonard J., chairman, Parsons Corporation; La Canada, Calif

SCHAFER, Capt. Tim, pilot

SCOVILLE, John A., chairman, Harza Engineering Company; Wilmette, Ill

TERNER, I. Donald, president, Bridge Housing Corporation; San Francisco

THOLAN, P. Stuart, senior vice president, Bechtel Corporation; London

TURNAGE, Tech. Sgt. Cheryl, steward

WARBASSE, Naomi P., international trade specialist, Commerce Department

WHITTAKER, Robert A., vice president, Foster Wheeler Energy International

Did you encounter any situation during your military service when you believed there was a possibility you might not survive? If so, please describe what happened and what was the outcome.

Maybe someday, but not today.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

Ramstein AB as a whole. The first three years were a special duty, Postal, during the first Gulf War. Working 6 or 7 days a week for 12 to 16 hours a day for 14 months was definitely hard work. We went from processing (pre-Gulf War) a single 40 ft. SeaLand container a week to an average of four, but plenty of traveling was to be done even then. Seeing the Porta Nigra in Trier, castle hopping up the down the Mosel and Rhine Rivers, wine festivals in Traben-Trarbach, Bernkastel-Kues, Stuttgart, Bad Durkheim and Oktoberfest in Munchen. Who else has ‘rested their eyes’ on the grassy hill by the fest tents?

On my second tour, I returned to my original AFSC 702 (later 3A0), and I got along great with a few fellow airmen who were up for traveling. Camping, hiking, rafting, riding, skiing, skydiving; MWR services were awesome in Europe. Together with a job that became a standard eight-hour-a-day, five days a week position, it allowed for travel on leave orders or weekend excursions to over 20 European countries. Barcelona Olympics in 1992, trips to Paris at 3 am with a certain lovely lady. We were eating regional foods in Tuscany and the Amalfi Coast…visits to Pisa and Rome.

Visiting the Salvador Dali Exhibit in Venice in 1995…count me in. White water rafting in Austria. Skiing in Germany, France, Austria, Switzerland, Italy (I accidentally skied down the wrong side of a mountain once).

Sadly Offutt AFB NE were the bookends of my service. I never cared for Omaha, but it was more than that. At age 18, there wasn’t much to do in the local area that didn’t get done in the first six months: Henry Doorly Zoo, the SAC museum (I was on the flight line when the SR-71 arrived in the summer of 1990), Spaghetti Works and a few open mic nights at the comedy club I wasn’t legally allowed to go inside the front door of. There are fond memories of a young lady who was enrolled at Creighton University. Yeah, I think about Nicky every once in a while.

Still, I took a special duty assignment to get out of there, and I returned six years later even though the base wasn’t on my list. It was amazing that people I had met in 1989 were still stationed at Offutt AFB in 1996 when I returned. Still, honestly, I met people in Germany in 1990 who were shocked when they returned years later (usually as a base of preference selection following a remote to South Korea), and I ran into them again.

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect back on to this day.

My memory is long. I remember the site and the sounds and faces of people whose names I don’t know anymore. Vibrant yellow hills were covered in mustard plants in Germany. Waving fields of corn in Nebraska. With the shimmering blue of the Adriatic outside the conference center, we conducted interviews in Cavtat, Croatia.

The clink of glasses in restaurants from toasts with friends filled with red and white wines, dry and sweet. Wursts and Schnitzel, cabbage salads and spaetzle, beer crystal clear and dark and heavy, Taco Bell at 3 am in London (hey, it was open). Warm summer nights watching the sunset in the Alps. Friends and lovers and laughter shared.

The reek of the rendering plant south of Offutt AFB that wafted off your clothes after walking from your car to the Wing HQ building. A special stench that deserves mention, lol.

Sadness, a few funerals for people taken too early defending their country. A plane crash and a few suicides I think about every…single…day. People that didn’t know how or who to ask for help.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

I was awarded Distinguished Graduate in my Airman Leadership School in 1995. This was both an academic and peer award. It was being chosen to augment the dedication ceremony of a section of the Berlin Wall for the 50th Anniversary of the End of World War II in Europe at Ramstein Air Base (1995) and being able to shake the hand of the dozens of WWII veterans living in Europe at the time that made it to the base that day. I still have the DV lists, lunch, reception, and dinner menus from the events, the speeches, invitations, and PowerPoint presentations from the day.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

The more I thought about this, the more it became apparent that everyone I met, worked with, and associated with; we’re part of the community and military family I loved. But if I were to narrow it down to one, I would say CMSgt Estrem, 55 WG/CCC. Working for him was hard but very rewarding. That duty assignment also allowed me to meet several retired Chief Master Sergeants of the Air Force. There was nothing like putting on CMSgt of the Air Force James McCoy’s putting green on his birthday in 1998. Good to see he just hit 90.

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

Ramstein

Maj Hibbs (Lt Col by the time I PCSd in 1996)

William “Ed” Cox (deceased)

Jackie Tuscysnki

Tammie and Tammy (The Tammys)

Kristie

Mike Hauter

Kerry Jacobsen

Robert (Bob) Luedtke – Former Security who cross-trained to Personnel. My boss in the 86 MSS Orderly Room. Great guy with a hilarious sense of humor. Watching him and Birgit have German language class was wonderful. Ruler…Lineal was pure gold since I still laugh about it 27 years later.

What profession did you follow after your military service and what are you doing now? if you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

After 702 transitioned into 3A0 and the role shifted to computers and supporting the user to the wall, my last few years were spent developing a class to acclimate new airmen to small computers, software applications, and personnel support. I was quite pleased when ACC poached my entire class, took my name off the study guide I wrote, and sold it back to my base the last six months of my time in. It was both very flattering and infuriating at the same time.

I stayed in IT after I separated, but I shifted to the transmission side of things. I built a fiber-optic network for a few years, then got out of data transmission and got degrees in programming and database design and administration along with several certifications for network administration and engineering. Strange to think I’ve now got 30 years of experience and how much things have changed since DOS 6.2, Windows 95, and NT 3.5.1 days.

Now I’m a senior solutions engineer for a Tier One supplier for an automotive company. This time I got to design and build my own network from the ground up in 2013. It’s nice literally know what every cable plugged into every device does and immediately know what is wrong when an issue occurs.

What military associations are you a member of, if any? what specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

Sadly I have a few service-connected disabilities, and the Veteran’s Administration and I are still going around on a few more.

DAV Life Member. They’ve assisted me with my VA appeals process, for which I’m very thankful.

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

I miss the mission and being part of a cohesive team working on completing an objective.

I miss the people, my Air Force family, especially supporting and taking care of them. I can recall hundreds of faces and names of friends, lovers, and acquaintances.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Air Force?

Get overseas, don’t buy a car, save 60% of your paycheck, eat in the chow hall, if you drink, don’t drive, always walk with a buddy, never count your money in public, don’t date a lady with a tattoo of a dagger on her inner thigh, smile, speak the language, be nice, get off base.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with.

I’ve already found a few people, and it’s a great place to consolidate memories and information.

Thanks, Kim. (You are most welcome, Richard!)

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

I believe SRA Richard Clark served in the USAF, not the USN. Not sure how to ID incorrect pages but he has a good (very good) reflections write-up.

SRA Clark should have been promoted to Staff Sergeant in the ten years he served. His experiences proved he was a good man.