PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

The following Reflections represents CMSGT Bruce Hanke’s legacy of his military service from 1967 to 2004. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Air Force.

Both my father and my uncle played a very significant role in my desire to join the Air Force. My dad was an Aviation Electronics Technician in the Navy during WW2 aboard the aircraft carrier USS Bennington, working on F4U Corsairs, F6F Hellcats, and TBF Avengers, and my uncle served four years in the Air Force, stationed at March AFB, Westover AFB, and Keflavik, Iceland in the early 1950s. Both of them held pilot licenses, but even though my dad was the eldest of the two, my uncle got his license first in his late teens at Felts Field in Spokane, WA.

Dad introduced me to the world of aviation via model airplanes, and he would often take me out to the local airport in Pasco, Washington, where I grew up, to watch airplanes take off and land. He encouraged me, helped me, and really got me started building model airplanes to the point it was a hobby that consumed much of my time during my grade school and high school years. I pretty much stuck to making that my number one hobby well into young adulthood, and since I grew up just after WW2, even as a kid, I could identify almost all aircraft flown by the Allied and Axis powers. Even in the 1950s and 60s, many companies were manufacturing model airplanes from all the countries that fought in WW2, and I built dozens and dozens of those scale model aircraft over the years. Eventually, I got into building balsa wood flying models and gasoline-powered U-Control airplanes.

My Uncle Roger got me my very first real airplane ride at a small airport in Bellevue, Washington, before I entered the Air Force, and that, to me, was just about the coolest thing on the planet up to that point. I set my goals early on – I was either going to fly or work on military aircraft, and I eventually followed through, making aircraft maintenance my lifelong career. I wasn’t interested in going to college after high school, so becoming a pilot was sort of out of the question at that point since I had two strikes against me: One, I wore glasses, and two, I needed a college degree to go to pilot training in the Air Force or the Navy so that option was out. Army helicopter pilot training didn’t require a degree, and wearing glasses was ok, so I briefly considered that option. The fly in the ointment was that one of my dad’s younger cousins was an Army helicopter pilot in Vietnam, and he’d been shot down three times before they finally sent him home. After thinking about it for a while, the thought of dying in Vietnam in the flaming wreckage of a helicopter was a bit of a show-stopper for me, so off to Air Force aircraft mechanic training I went instead.

Interestingly enough, half a century or so later, I decided to pursue a private pilot’s license at the ripe old age of 74 and have already logged a few hours to that end. Unfortunately, the flight school I attended shut down in 2023, but I’d still like to pursue a PPL even though more than a year has passed since I last flew. At 75 years old, shooting for a PPL may be a bit of a difficult goal, but I still want to give it a shot.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

I entered the Air Force in October 1967 and went through basic training with the 3706th BMTS, Flight 1358, at Lackland AFB, Texas, followed by technical training, assigned to the 3369th Student Squadron at Chanute AFB, Illinois. I trained to be an Aircraft Instrument Systems Specialist, found it to be interesting and very challenging, and came to be quite proficient at troubleshooting and fixing whatever malfunction came along. That AFSC exposed me to every complex aircraft system – pitot-static systems, flight and navigation systems, engine instrument systems, fuel quantity indicating systems, and any variety of instrument systems that monitored anything and everything on an airplane. Eventually, the AFSC would merge with Automatic Flight Control Systems (Autopilot), and I would learn and master an entirely new and complex system.

My first real duty assignment saw me getting immediately thrown into the fray in Vietnam with orders directing me to proceed to Tuy Hoa Air Base right after tech school. Apparently, the Air Force didn’t see my request for an assignment in England to have tea with the queen as being in their best interests, so I went off to the jungle instead. Eighteen months with the 31st Tactical Fighter Wing in Vietnam, working primarily on F-100 Supersabres was followed up by another year and a half-tour of duty with the 6200th Air Base Wing at Clark Air Base in the Philippines working Base Flight aircraft. We operated C47s, C-54s, C-118s, H-19s, and T-39s, and I worked on all of them. I don’t think I fully appreciated how cool that was until many years later. After reluctantly departing Clark Air Base in early 1971, my final active duty assignment was with the 438th Military Airlift Wing at McGuire AFB in New Jersey, working on C-141As.

About a year or so after bailing out of active duty, in December of 1972, I joined the 905th Tactical Airlift Group – an Air Force Reserve unit at Westover AFB, MA, for about six months; then in June of 1973, I transferred to the 143rd Special Operations Group – an ANG unit in Rhode Island which was flying C-119L’s and U-10D’s at the time. We eventually became the 143rd Tactical Airlift Group after a mission change to C-130A aircraft in 1975, and I served with them for a total of twelve years before transferring to the 163rd Tactical Fighter Group, California Air National Guard in 1985, where I went to work on F-4’s. After several aircraft conversions and mission changes, the unit eventually became the 163rd Air Refueling Wing flying KC-135s, the unit from which I retired in 2004.

I initially entered the Air Force with the intention of making it a career from the outset; however, after about three years and a series of incidents that reshaped my plans, the Air Force, largely unbeknownst to them, actually talked me out of that idea. I decided that as much as I loved working on airplanes, I didn’t need or want bureaucratic hassles and wasn’t going to make the active Air Force a career after all, and I was honorably discharged in October 1971 at McGuire AFB.

My first three years after basic training and tech school were all spent overseas, first at Tuy Hoa Air Base, RVN, for 18 months, followed by another year and a half at Clark Air Base in the Philippines, as I mentioned previously. While at Clark, I met and married the love of my life, but the Air Force, or at least those in my chain of command, frowned on that idea big time. In those days, a GI marrying a Foreign National was not something the military looked favorably upon, especially if you were under four years in service. I was under four and endured an exceptional amount of resistance in trying to get married, jumping through a never-ending bunch of bureaucratic hoops, and getting the proper documentation and permissions to marry and bring my wife Elizabeth home to the States. To add insult to injury, I would be required to pay her airfare back to the States entirely unless I was “over 4”. I tried my best to remain at Clark for my last six months in service and even offered to re-enlist if I could stay there and extend my tour. No one was interested in helping me out, with the exception of one of our Maintenance Officers (but even his efforts were to no avail). Every turn was met with resistance, so I took the transfer to McGuire AFB in New Jersey for the last six months of my four-year commitment and borrowed money from the Red Cross to get my wife to the States. I arrived home completely broke, in debt to the Red Cross, and my plans to make the Air Force a career completely dashed. I’d honestly had enough of bureaucratic roadblocks (I have another term I prefer to use, but you get the idea), so I got out of the active Air Force and couldn’t get out soon enough.

After discharge in October 1971, I attended a six-week training program under “Project Transition” at the GM Training Center in Moorestown, NJ, learning to be an auto body and paint technician, followed by a job at a Chevrolet dealership in Wakefield, RI, near where I lived after finishing the auto body and paint course. That job only lasted about six or seven months, as I was struggling to raise a family on $1.75 an hour, even in 1971-72 when gas was less than 30 cents a gallon, so I landed a job at the local Navy base making more than double what I was raking in at the Chevy dealership. Landing that federal job at Quonset Point Naval Air Rework Facility overhauling aircraft instruments was a lifesaver to me at the time, but little did I know the base would be shuttered a year later with very short notice.

At the persistent urging of a co-worker at the Navy base, I joined the Air Force Reserve at Westover AFB in Massachusetts along with another co-worker, Phil Osgood. We both wanted to get back into aircraft maintenance, but the co-worker who conned us into joining up in the first place told us there were no openings in maintenance. According to him, although we could get into the Reserves, only the Aerial Port Squadron was open to us. I’m pretty sure he wasn’t telling us the whole truth, and as it turned out, he was in the upper ranks of the Aerial Port Squadron, but into the 59th APS we went anyway, where we retrained to handle air cargo, but that would only last about seven months. During those seven months, we all lost our full-time jobs at the Quonset Point Navy Base due to base closure. The monthly drive to Westover AFB for Reserve duty was getting a bit old anyway, so we both decided to transfer to the R. I. Air National Guard at T.F. Green State Airport in Warwick, RI, and into aircraft maintenance, which was what we both wanted anyway. Phil only stayed a couple of years or so after that, but I stayed on and served 12 years as a full-time technician with the RI Air Guard before transferring to the CA Air Guard in 1985, also in a full-time position. I retired in 2004 with 37 years total time in service with Air Force Active Duty, Air Force Reserve, and the two Air National Guard units.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

During my 37 years of service, I had plenty of opportunities to participate in a number of military operations, the first being the war in Vietnam. I served at Tuy Hoa Air Base, the largest F-100 Supersabre base in Vietnam, from May of 1968 through November of 1969. Our job in the 31st TFW was to provide close air support with our F-100s, and my job was maintaining the instrument systems on those F-100s and most all other aircraft assigned to Tuy Hoa Air Base. I was assigned to the 31st Armament and Electronics Maintenance Squadron when I arrived. Still, not long after, the Air Force realigned the whole shebang, the marriage of Armament and Electronics was dissolved, and we became the 31st Avionics Maintenance Squadron. I suppose the Armament guys moved to another facility, but I don’t remember. We also trained for air base defense as Air Police Augmentees along with our regular jobs, manning perimeter foxholes from time to time and learning to fire the M-60 machine gun so we could man the perimeter positions we were assigned to if needed, along with carrying our personally assigned M-16A1 rifles. We operated 24/7/365 to support ground troops in the field, and nearly all of our operations were in-country South Vietnam, with some purported and definitely unauthorized excursions over the border into Cambodia, Laos, and North Vietnam. We lost several good men to enemy fire as well as to a few unfortunate aircraft accidents over the years – men who really should still be with us. It’s hard to think about that without getting sad and perhaps a little angry occasionally. During the 18 months I was there, we lost 16 pilots alone to combat action or accident at Tuy Hoa. Two of the pilots and both of their airplanes disappeared after a mission when they were diverted to another base due to weather and were never heard from again. They never arrived at the diversion base, and their aircraft and remains have never been recovered. If I had to make an educated guess, they more than likely ran out of fuel over the South China Sea and either ditched or ejected, never to be found, but at this point, it’s merely conjecture on my part.

One of the more interesting aspects of being at Tuy Hoa was having two Air National Guard units join us for about 11 months – the 188th TFS from the New Mexico ANG and the 136th TFS from the New York ANG. They performed very well and integrated with us seamlessly. At the time, I was quite unfamiliar with the Air National Guard or Reserves, but those 11 months the Guard guys spent with us opened my eyes to what the Air Guard was all about, and I’m still friends with some of those guys more than 55 years later. Little did I know then that I would find myself in the Air Guard not so many years later. Another of the more unique aspects of our missions at Tuy Hoa was when two more squadrons of Supersabres joined us when they moved down from Phu Cat Air Base in June of 1969 after the two Air Guard units left for home. One of those squadrons that joined us from Phu Cat operated the famed Misty “Fast FACs” (Forward Air Controllers) of Operation Commando Sabre. Most of our aircraft were the single-seater F-100Ds except for the single-seater older F-100Cs the Air Guard flew, but the Commando Sabre guys flew the two-seater F-100Fs. Call sign “Misty 1” was Col. George “Bud” Day, who’d been shot down and made a POW before the Misty FACs came to Tuy Hoa. He was not released until 1973, along with the other POWs.

Besides Bud Day, there were several other Misty FAC pilots who went on to make a name for themselves after their “Misty” days, guys like General Ronald Fogleman, who became the commander of Military Airlift Command, Commanding General of US Transportation Command, and finally Chief of Staff of the Air Force. Another Misty FAC pilot, General Don Shepperd, became Director of the Air National Guard. Both Fogleman and Shepperd exited Commando Sabre before the operation was transferred to my base at Tuy Hoa, so I never met either of them at the time, but I genuinely feel honored to this very day for having had the opportunity to work on those Misty Fast FAC aircraft and be a small part of Misty history. Of the 157 Misty pilots, 34 were shot down during those FAC missions, and two were shot down twice. Of the 157, seven were killed in action, and four were held as POWs, including Captain Guy Gruters, who I talk about in the last segment of these “service reflections.” Vietnam in the 1960s was very much a life changer to everyone who went over, as anyone who has gone to war and been the “man in the arena” can attest to, and for all kinds of reasons. 2.7 million, mostly guys and a few women, served in-country in Vietnam, and there are 2.7 million different stories. I’m just one of those 2.7 million stories; of those 2.7 million, it is estimated that only 610,000 of us are still alive today. It’s a bit disturbing to realize we’re dropping off the grid faster than we care to, but that’s life and death in the big city. Those 18 months in Vietnam will be with me as long as I live, and I suspect the experience has defined me and almost everybody else who served “in-country” in more ways than we probably comprehend.

Some years later, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I would participate in several “Volant Oak” real-world deployments to Panama with the Rhode Island Air Guard in support of US Embassy missions and a wide variety of other support activities, some clandestine, throughout Central and South America, including one mission where we delivered what was marked on the crates as “cleaning supplies.” Those “cleaning supplies” turned out to be M-16s and ammo, compliments of the US Government being delivered via our C-130A to a very corrupt and collapsing government of one Anastasio Somoza of Nicaragua during their civil war against communist-backed guerillas in 1979. It was a very dangerous time in both Nicaragua and El Salvador, and the government finally collapsed not long after our little foray into the heavily fortified airport in Managua. During our very brief time there, we could clearly see all around us that the proverbial crap was going to hit the fan shortly, and we really couldn’t get out of there fast enough. All those M-16s and ammo we delivered to Somoza’s forces, unfortunately, wound up in communist rebel hands. Nicaraguans merely traded one corrupt banana republic dictator for another. Daniel Ortega is still in charge more than 40 years later – only slightly better than the very corrupt Anastasio Somoza he overthrew. You never knew what you were going to get in the luck of a Volant Oak draw until it happened.

Moving on into the 1990s and 2000s, after working my way up the food chain and taking over as Aircraft Maintenance Superintendent in the CA ANG’s 163rd ARW, I would deploy several times to Europe with our unit’s KC-135 in support of no-fly operations over Kosovo as part of Operation Joint Endeavor, Joint Guard, and finally, Joint Forge. Our portion of the operations in which I participated operated initially out of the Italian Air Base at Pisa in 1996. Eventually, the operation moved to a French Air Base, BA 125, in Istres, France, where I would deploy three times. My last Joint Forge deployment was just a few weeks before I retired in 2004. As serious as the task was, being deployed to Southern France was one of the greatest opportunities I had while part of the Air Guard and one right at the top of many highlights of all my years in the USAF. Additionally, it gave me plenty of opportunities to brush up on and use four years of very rusty high school French.

The last operation I participated in before retiring was a KC-135 medical AirEvac mission throughout the Pacific Theater. One function the KC-135 was certified to do besides aerial refueling, cargo hauling, and passenger movement was medical AirEvac, and I got the opportunity to be part of that before retiring. We flew to Travis AFB and met up with a medical unit based out of Ohio. They outfitted our aircraft with litters and all the appropriate medical equipment for the AirEvac run we were about to undertake with them. We proceeded to fly to various bases in the Pacific on standby AirEvac for whoever might need us. We eventually picked up a patient in serious condition and flew him back to the medical center at Travis AFB. The medical Air Evac crew we supported gave each of us on the tanker crew an honorary KC-135 MedEvac patch tab for our flight suits. Upon our weekend return to March ARB and with very little fanfare, the rest of the crew doused me with Champagne for my very last flight in a KC-135 before retiring.

Did you encounter a situation during your military service when you believed there was a possibility you might not survive? Please describe what happened and what was the outcome.

There were a few situations during my time in the USAF where things got a bit sketchy. There were certainly incidents that could possibly have been the end of me had something gone sideways, but in the heat of the moment, everything moves so fast that you just don’t entertain those thoughts until after it’s all over. A couple of months after my arrival at Tuy Hoa Air Base, we were attacked by Viet Cong “sappers” who managed to get through the barbed wire fencing and onto the Flightline with the intent to blow up as many aircraft as possible with their explosive satchel charges. I worked the midnight shift during most of my 18 months in Vietnam, so I was on duty that night. Fortunately, I happened to be in the maintenance shop instead of on the flight line when the first airplane blew up. With that first explosion, we all immediately jumped, grabbed our M-16, and headed out into the dark. As in all similar situations, chaos reigns supreme in the fog of war, and this time was no exception. With bullets flying from both friendly and enemy fire, we took cover behind some boulders and vehicles in front of our squadron maintenance building, adrenaline making our hearts pound like crazy, to use a bit of a tired old cliche. One or more rounds hit the metal building behind me, ending up in the latrine. Fortunately, no one was hit, and it did not take long for our Air Police (now called Security Forces) and Army helicopter gunships out of Phu Hiep Army Airfield to respond. Those gunships lit up the village just outside the wire where the nine sappers attempted to escape, and the Air Police managed to send every one of those Viet Cong sappers to meet their maker. We had a front-row seat to all of it. The date was the wee hours of July 29, 1968, and I’ll literally never forget that night as long as I live.

Another incident that got my heart rate pounding away was during an excursion into Tuy Hoa City. Tuy Hoa City was about five kilometers or so from the air base, and despite there being a MACV (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam) compound in the city, Tuy Hoa City was often off-limits due to enemy activity and was always off-limits to military personnel after sundown. One day, as I was browsing the various shops in town, gunfire erupted somewhere nearby, and in a split second, every single shop was shuttered, and the streets became an immediate ghost town. With nowhere to hide, I hid the best I could by hitting the ground to make as low a profile as possible. As strange as it might seem in a war zone, we were not permitted in town with our rifles, so there I was, unarmed and very vulnerable. Whatever happened, I’ll never know, but it didn’t take long for shops to reopen, and everything got back to normal.

Many of the guys at Tuy Hoa Air Base were afraid to leave the base for their entire tour in Vietnam and never got to see anything of the country where they spent a year or more. That was definitely not me – I was young, dumb, and very adventurous, and despite the approximately five-kilometer distance into Tuy Hoa City from the base, going off the base was routine and an everyday experience for me. That gunfire incident in Tuy Hoa City didn’t deter me in the least – I enjoyed visiting the Buddhist temples, the Catholic Church, the orphanage, eating Vietnamese food, and just generally hanging out, so it was just too much a part of being in mysterious Vietnam for me not to experience it. I made friends with a local family who ran a photography studio and with their kids, as well as the kids who hung out there selling sodas and snacks to the GIs who came to town. They often showed me around, and I enjoyed their company. I still remember the children’s names – Tony, Tong, Lee, and Mai (I’m quite sure Tony’s real name was not Tony – she just didn’t look like a “Tony” to me!). Just before I left Vietnam for good in November 1969, I gave my watch to Tong, a watch I was presented with from my days as a newspaper carrier in high school. Tuy Hoa City wasn’t all that large back in the late 1960’s, but I don’t think I managed to see as much as I would have liked. Maybe a fear of getting too far off the beaten path contributed to that, but today, Tuy Hoa City is huge and has a modern airport where the base once was, and I hope to return there before I get too old to do so. I clearly remember a Korean bar and restaurant in town back then that catered mainly to the Korean forces base not far from our base. That’s where I first tasted yaki mandu, a delicious fried dumpling that I still love to this day. Despite a few close calls, we were relatively safe from the enemy at Tuy Hoa Air Base.

After my 18 months in Vietnam were up, I got the opportunity to be re-assigned to Clark Air Base in the Philippines, an assignment I requested in exchange for extending my tour at Tuy Hoa and going from a fairly primitive existence in Vietnam to the much more modern, clean, and beautiful tropical paradise of The Republic of the Philippines was like dying and going to heaven. Life had taken a noticeable turn for the better for me, and I couldn’t be happier! Despite all that was good, I did experience a couple of events that could easily have ended badly. I had a small apartment off base, and one night, while heading to the base for my work shift, I managed to find myself alone in a passenger “jeepney” with about three or four Filipino guys. Jeepneys are a normal mode of cheap public transportation all throughout the Philippines. I’d taken them to work or shopping many times, but something seemed off on the night in question, and I immediately sensed danger as soon as we started rolling. I tensed up almost immediately and braced myself for whatever was about to go down. Sure enough, the driver chose a dark side street to rapidly duck into. In those days, the Philippine Huks were very active communist insurgents who were known to kill American servicemen, and several guys from Clark never left the Philippines alive, all at the hands of left-wing murdering Huk wackos. So there I was, about to be murdered or maybe only robbed, but I wasn’t going to have any of that, so I made a bold move and jumped from the back of the moving jeepney. The dirtbags immediately grabbed me while the driver screeched to a stop. To use another really tired cliche, they were on me like white on rice, but I fought them for all I was worth and managed to fight them off to the point where they took off, leaving me on the street, a bit bloodied from a wound in my side which I may have gotten either from a knife or perhaps by being dragged behind the moving jeep, and with torn clothing and a missing shoe left behind in the back of the jeepney. The funny thing is, I didn’t have any money on me other than a 25-centavo piece I was going to use to pay for the ride, so if they planned to rob me, they got nothing! If they planned to kill me, they failed in that, too! Ironically, or perhaps providently, the location they chose to attack me was in front of a Catholic Church. I can still envision the front of that church to this day – maybe it was providence that saved me from a terrible fate that day. Who knows? That incident wasn’t the only brush with the possibility of injury or death during my days at Clark.

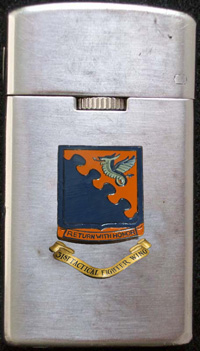

Another misadventure occurred several months later when my fiancee, one of her girlfriends, and I attended a Filipino movie in downtown Angeles City late at night. We came out of the movie house after it was over and were walking down a side street toward the main drag when very suddenly and with no warning, there were three guys on us, one of whom put a knife to my throat while demanding money from us. I gave them my wallet and the lighter that I’d gotten from my old base in Vietnam with our unit logo on it. Losing that lighter bothered me more than losing my wallet because I’d given all of my vast Airman First Class fortune that I had on me to my girlfriend (she later became my wife for life, may she Rest In Peace) to hide in her bra, so once again, the scumbags got very little besides my 31st TFW lighter and my fiancee’s girlfriend’s watch. Having a knife stuck in one’s throat is not a particularly pleasant experience, and it made me much more careful and aware from then on. On a positive note, I found the same kind of lighter on eBay 40-some years after my original was robbed from me – apparently, someone else (or their kid) formerly based at Tuy Hoa decided to sell their lighter on eBay, and I snagged it!

The closest call I ever came to actually getting killed while in the Philippines occurred some weeks or maybe months earlier than the knife-at-the-throat incident. One day, I was going back to base and had just gotten dropped off at the jeepney pickup and drop-off location near the main gate to the base. In front of the base back then, tracks belonging to the Philippine National Railway ran directly in front of the base through town, and I was just meandering along deep in thought and paying no attention to anything. Quite abruptly, I found myself being jerked backward by the collar of my shirt by a Filipino guy who was paying far more attention to what was going on than I was. Just as he pulled me back, a very large locomotive with a bunch of train cars attached passed millimeters in front of my face. That Filipino dude had very clearly and unequivocally just saved my life! The impact of the moment didn’t immediately register, but I think I managed to thank him and proceeded to go through the base gate and got on the bus to the main part of the base. Shortly after taking a seat in the shuttle bus, what had just happened at the train tracks hit me very, very hard as I began to shake very much uncontrollably. I shook for a while before finally settling down and regaining composure. The part that bothered me then and bothers me to this day is that I don’t know who the guy was who saved me from being flattened on those tracks. At the time, I didn’t grasp what he did for me, but I hope he knows how much I appreciated his heroism.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

Of the active duty assignments I experienced, I’d have to say Clark Air Base was clearly my favorite one of the bunch. It was where I met and married my beautiful wife, Elizabeth, and began life as a family man. She was someone who was very special, and I felt really lucky to have had her in my life. Besides, who wouldn’t love living in a tropical paradise with great beaches, good food, and great friends? I got plenty of opportunities to travel around the northernmost island of Luzon, from beaches to remote mountain villages and bigger cities, and those adventures were some I’ll not soon forget. One time, I traveled with some Filipino friends high into one of those remote mountain villages I just referred to where the family of one of my friends lived. We parked the car in the town at the base of the mountain, hiked for several hours up into the dense forest, and eventually arrived at our destination. The village was fairly small and had no running water or electricity, but the people treated me like royalty. We stayed overnight, sleeping on bamboo mats, and before turning in, we sat around a campfire drinking warm San Miguel beer and snacking on purple sweet potatoes. That was quite an experience for someone like me who lived a pretty comfortable life with all the modern conveniences, sharing stories with people who had practically nothing but enjoyed their life as it was. While in the Philippines, I traveled around in Jeepneys (converted WW2 military jeeps converted to carry passengers), rickety Philippine Rabbit buses, and sometimes I used my friend J.C. Weller’s 1956 Ford – it was certainly a carefree time in my life without a doubt. I eventually got my own car when I bought a 1963 Ford Custom from my friend Fred Angst when he rotated back to the States. As a side note, J.C. Weller, Fred Angst, and I were all at Tuy Hoa together before reassignment to Clark, along with two other guys, Keith Knowlton and Bill Hill.

My least favorite assignment was my final active duty posting to McGuire AFB in New Jersey. In those days, I couldn’t afford a place in New Jersey, not even out in the boonies where McGuire was located, so I ended up leaving my wife in Rhode Island at a house we rented there not too far from my parent’s place until I got out of the Air Force six months later. I drove 240 miles one way back and forth every week to spend a couple of days with my wife and new baby, and despite gas costing only about 28 cents a gallon, it was difficult to afford the gas, rent, utilities, and food on only about $300 and change a month, before taxes.

As for favorite assignments while in the Air National Guard, I’d have to say they were mostly all pretty good, with TDY’s to Howard AFB, Panama, Pisa, Italy, Geilenkirchen, Germany, and Istres, France being on the very top of the list. Our frequent deployments to Panama were in support of the Volant Oak missions to support US Embassy operations throughout Central and South America and the Caribbean with whatever was required and sometimes included some interesting taskings. One very memorable task involved transporting the US Army Band around Brazil – first stop, Manaus in the middle of the jungle for fuel, then on to Brasilia and Sao Paulo we went. While in Brasilia, we were treated to all lodging and meals in a very nice hotel, compliments of the Brazilian government. Another task was the incident in Nicaragua I mentioned earlier, which was also on one of those Volant Oak runs. One of the great perks of those operations was shopping on the local economy for such items as Colombian coffee, Peruvian llama wool blankets, and Salvadoran Terry Cloth towels straight from the source, to name a few. I remember one trip to San Salvador just before the Civil War, where some of the guys bought a bunch of lamps that looked like covered wagons. After our tour of duty was over, on the trip home back to Rhode Island, everyone hung their wagon lamp from the static line cables on both sides of the cargo compartment so as to keep them from getting damaged on the trip home. It was actually quite a comical sight. I thought the lamps were rather tacky, so I never bought one.

Our assignments to Pisa, Italy, and Istres, France, were in support of Operations Joint Forge, Joint Guard, and Joint Endeavor, all of which were essentially part of the peacekeeping operations in the days that NATO instituted a no-fly zone over the Balkans. Those trips provided some outstanding opportunities to see Europe while off duty that most never get to see. I do miss those days immensely. The TDY’s to NATO Base Geilenkirchen were in support of refueling missions of NATO E-3 aircraft and always meant we got Saturdays and Sundays off duty. Apparently, NATO doesn’t work weekends. Our return trips back to March Air Patch always entailed returning home with our KC-135 cargo compartments loaded with German beer and wine, and I do mean loaded. Upon arrival back at March, US Customs would sometimes shake their heads at seeing what we brought back, but they never gave us a hard time about it and usually looked the other way when it came to imposing duty taxes on us.

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect back on to this day.

With all those years in the Air Force, Air Force Reserve, and Air National Guard under my belt, there are loads of memories to look back on and reflect upon – mostly all good ones, some not so much. I was actually pretty lucky throughout most of my career insofar as avoiding serious trouble. Still, perhaps the one memory that sticks with me more than any other is the incident of July 29, 1968, when a VC (Viet Cong) sapper squad infiltrated our base and tried to blow up as many of our airplanes as they could, as I talked about in a previous segment. They succeeded in part, but all of them lost their lives in the process. Under normal circumstances, an old hand would likely have taken that attack in stride, but being a very young 19-year-old and not quite three months fresh in-country, it left one hell of an impression on me, one which has lasted my entire life.

Some of the best memories old Air Force wrench turners have are of the airplanes we worked on, and almost always, the strongest memories are those of the first aircraft we worked on. For me, the F-100 Supersabre is that aircraft, and although it wasn’t one of the ones I worked on the longest, it will always have a special place in my heart. I cut my teeth on that airplane, and it will likely always be my favorite. I quit building and collecting model airplanes a long time ago, but I do have four model F-100s and am working on a 1:72 scale diorama of a portion of our Flightline complete with revetments at Tuy Hoa Air Base to display some of my die-cast model F-100’s. I hope to bring it to our next reunion. The F-100 in the photo is of a 306th TFS Hun at Tuy Hoa during my time there. I didn’t take this particular photo, but I think the photographer was Dick Larsen, one of our base PA guys at Tuy Hoa, who has been very gracious about sharing some of his awesome photos from so long ago on our reunion page.

Of course, my fondest memory of my time in service was meeting and eventually marrying my wife, Elizabeth. I was really a very lucky man but definitely a bit blind to that fact until somewhat later on down the road of life when I matured (somewhat) and began to understand what good fortune I fell into and what life was really all about. We had three great children – two girls and one boy, and seven wonderful grandchildren, all of whom turned out to be normal and productive members of society. One can’t ask for any better than that. I’m very proud of all my children, and their mother would be proud of them as well if she were still here to see it all. I give her all the credit, for she was the stay-at-home mom who did her very best to ensure all the kids were well-fed, schooled, loved, and given the best care anywhere. I’d have to say that although our lives were often a struggle financially, we didn’t seem to notice all that much. We did ok, and I’d not trade my 29 years with her for anything in the world. Unfortunately, I lost her to cancer five years before I retired from the military, but she is, without a doubt, the greatest memory I could possibly ever have. What does that memory have to do with military service, you ask? Well, were it not for the Air Force and the assignments they handed out to me, one of which was a short TDY to Clark Air Base out of Vietnam, I would never have fallen in love with the Philippines, I would never have requested a follow-on assignment to Clark, I would never have met the woman who I would later marry. I would not have the wonderful family I have today.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

In the 1970s and 1980s, when I was with the 143d Tactical Airlift Group, Rhode Island Air National Guard, I worked part-time on getting a BA at the University of Rhode Island. I took a number of English Literature and Creative Writing courses, and I thought I was progressing fairly well with my writing ability, so I decided to enter an annual writing contest sponsored by Military Airlift Command’s Flight Safety Office out of Scott AFB, IL. MAC published a monthly flight safety magazine at the time, entitled “The MAC Flyer,” and once a year, they’d solicit articles or stories from the hoi polloi related to flight safety. They’d select the top 12 submissions they considered the best and publish one every month in the upcoming year. The top three would be First, Second, and Third Place, followed by nine runners-up, and they’d be published in order of contest placement. I really enjoyed reading the magazine every month, so I decided to give the writing contest a go. The first year I entered the contest, it met with no joy, but lo and behold, with the second year’s attempt, my entry was a “runner-up,” and it was published later that year. I was jazzed at seeing my submission in print. I continued to enter the writing contest for several years afterward. Eventually, I took a first, second, and third place entry, not necessarily in that order, and I won a number of runner-up wins over the years. Looking back, I’m not sure some of the stories of an enlisted maintainer were all that impressive compared to some of the submissions from Military Airlift Command’s professional college boy aviators, but apparently, the staff of The MAC Flyer must’ve thought they were good enough. I felt a sense of accomplishment with each win. It was pretty cool to see my name and contest entry printed in “The MAC Flyer.”

Another professional accomplishment that meant a lot to me was being named Air National Guard Senior NCO of the Year for the entire state of California in 1988 and named the National Guard Association of California’s Outstanding Senior NCO of the Year for 1989. In conjunction with another guy from my previous unit, we developed a fairly detailed and comprehensive safety program for our unit in Rhode Island. When I transferred to the California Air Guard, I brought it with me, rewrote part of it, and adapted it to my new unit. It apparently caught someone’s attention in a most positive way and eventually played a role in getting me named Senior NCO of the Year for the unit and the entire state. California had (and still has) four flying units and quite a number of smaller non-flying units, so it was quite an honor to be recognized in such a way. What made it all the more an honor was that I had not been in the California Air Guard all that long, having transferred from the 143d TAG in Rhode Island less than two years earlier.

Another professional accomplishment involved a new piece of aircraft test equipment, the GTF-6 Test Set, used for calibrating, checking, and troubleshooting Fuel Quantity Indicating System problems on the C-130A that we were flying in the RIANG at the time. We received the piece of equipment to replace what the Air Force considered to be outdated pieces of test equipment, the MD-1 and MD-2A test sets. No specific technical data instructions for the new test equipment applicable to the A model C-130 had been written, and I noticed there were some quirks with it, so I submitted a couple of additions or corrections to the C-130A tech order to the WRALC engineering department at Robins AFB, GA. Some weeks later, I received a call from them thanking me for my input, and they asked me if I wouldn’t mind rewriting the entire procedure for the new piece of equipment as it related to the C-130A. I agreed and spent a fair amount of time and effort to complete the work, including making up what I considered relatively primitive drawings and diagrams to illustrate adapting the GTF-6 Test Set to the aircraft. I figured the engineers would come up with more professional drawings before implementing the new procedures into the tech data. Several weeks or maybe months after submitting my work to the WRALC program office at Robins AFB, all the C-130A units received a new updated Tech Order for the Fuel Quantity Indicating System in which they used my entire submission word for word, including drawings and diagrams exactly as I had submitted with not one single change. Although no awards were involved, it was a significant and positive contribution to C-130A maintenance, an achievement I took a great deal of pride in seeing through from start to finish.

Another milestone accomplishment involved assisting the Air Force Depot at Robins AFB, GA, in a foreign military sales program – twice. During my years working on F-4E Phantoms (1987-90), I was shop chief for the Avionics Photo-Sensor Shop, where we maintained the Pave Spike Electro-Optical Laser Targeting System. The main component of the system was a pod that we mounted under the fuselage on an as-needed basis if a precision laser-guided strike was on the frag order of the day. About two or three years or so after we transitioned out of the F-4E, I received a call from the Pave Spike program manager at Robins AFB, who tracked me down and asked me if I could help them prepare a dozen Pave Spike pods for the Israeli Air Force which was operating F-4E aircraft with the Pave Spike system at the time. I secured the assistance of one of my troops who previously worked with me during our Pave Spike days, and off we went to Georgia. My former co-worker Doug Rader and I spent about two weeks getting the dozen Pave Spike pods into a serviceable condition for the Israelis. Mission accomplished! About a year or two later, the same program manager called me again, asking if we could repeat our prior performance, but this time for the ROK Air Force. Once again, Doug Rader and I headed off to Georgia to work our magic on a number of Pave Spike pods that would prove to be more of a challenge than the ones we prepped for the Israelis. We managed to complete the job and left Robins AFB with the satisfaction of once again a mission accomplished! The ROKAF still operates their F-4E aircraft, and I sometimes wonder if the Pave Spike pods we worked on for them are still in use. The ROKAF has scheduled their F-4 fleet for retirement in June 2024, so even if the pods are still in use, they’ll all likely be museum pieces shortly!

One major effort in which I played a part was setting up and overseeing the March ARB site for the KC-135 PACER CRAG Avionics modification program. Sometime around 1996 or so, at the request of my Group Commander, Col. Jacob Leisle, I was attending the initial planning meetings at the Rockwell Collins factory in Cedar Rapids, IA, and at the Air Logistics Depot at Tinker AFB in Oklahoma as he wanted to ensure the Air Guard was represented by someone in our unit, especially since the ANG flew the majority of the KC-135 aircraft in the inventory, and during one of the meetings at Tinker AFB, the program manager asked if anyone could host a modification line or two at their base. I remember thinking that March was ideally suited for a whole host of reasons, so I called back to my Group Commander and proposed that we host two mod lines. He readily agreed, and I offered our unit up as a host unit. The Program Manager jumped on our offer, and after much planning and jumping through a lot of hoops, we actually established four modification lines, with Raytheon being the prime contractor for the mods. The Air Force Reserve unit at March wanted in on the action, so they jumped on the bandwagon for two of the mod lines, with the Air Guard running the other two. We at March ARB became the largest modification facility in the country for the largest Avionics modification program the KC-135 had ever seen in its life span, and I had the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to help get it off the ground with an incredibly talented team and oversee its very successful implementation.

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

This may seem a little strange to most, but I’d have to say my Vietnam Service Ribbon, along with my Vietnam Campaign Ribbon and Vietnamese Gallantry Cross with Palm device, means more to me than any of the other awards and decorations we typically receive during our service time. The Vietnam medals represent a difficult time in my life as well as representing a fairly large chunk out of my life. The VSM is essentially a “been there, done that” award, but it’s important to me for all it represents. My VSM had six campaign stars, covering six different phases or campaigns of the War in Vietnam.

In the category of individual meritorious or commendation medal-type awards, the first of my two Meritorious Service Medals meant more to me than any other individual awards because the troops who worked for me at the time initiated the award and saw it through to presentation. I had no idea what they were doing until it was presented to me in an awards presentation event, and I really felt honored that they thought well enough of me to do what they did and to make it even more meaningful; it was somewhat rare at the time to have an enlisted person receive the MSM. Now, it’s quite common, if not expected, in today’s Air Force, especially in the upper enlisted ranks. At the time, I was the Sensor Shop Chief in the 163d Avionics Branch of the 163d Reconnaissance Group, and the Sensor Shop was the largest shop in the Avionics Branch, with 29 specialists and technicians assigned. We had a very tight-knit and cohesive group of people who managed to consistently deliver reliable aircraft systems and photographic images to the 163d Operations Squadron. They apparently attributed the success of all that to me, but since there’s no “I” in team, I really have to lay all of our successes at the feet of my troops because they were talented and very competent. I look back at that particular period in my career as a tremendous success for my first larger-scale supervisory experience in a relatively high-profile position.

What profession did you follow after your military service, and what are you doing now? If you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

I worked alongside a lot of talented mentors starting in Vietnam, one of whom was my first OJT trainer, SSgt Terry Roberts, and we are still in touch to this day 55 years later. One of the assistant shop chiefs, TSgt Hershel Hutto, was also one of those truly decent and calm-under-fire types who took good care of his troops. Everyone looked up to him, and he was the one who looked out for his guys. We became good friends, and he even invited me to visit him at his home on Cape Cod after we both got home. Unfortunately, too much time had passed before I ever made it back home, and we lost touch. While writing this, I decided to see if I could track him down on the internet, and unfortunately, I learned he passed away back in April of 2009 in Georgia. Rest in Peace, TSgt Hutto.

At McGuire AFB, it was my shop chief, TSgt Zigmund Korzinski, who I remember as being the ideal mentor. He epitomized a great supervisor whose guiding hand and calm approach to our daily activities made one feel like a valued part of the team. I decided also to try to track him down while writing this and discovered, to my dismay once again, that he, too, passed away in New Jersey in 2012. I’ve never forgotten his fatherly demeanor and the fact that he was such a decent person who looked out for us all. He was another TSgt Hutto, in my opinion. Rest in Peace, TSgt Korzinski.

In the RI Air Guard, I’ll never forget my Avionics Chief, Bob Habershaw – may he Rest in Peace. He was a great guy, honest as they come, and always backed his guys to the hilt. Along with Bob Habershaw, my number one mentor was Russ Hadfield, who taught me the meaning of a quality job and helped instill in me a great work ethic and a professional approach to everything I did when it came to aircraft maintenance. Russ also retired as a Chief, and we still keep in touch almost 40 years after I departed the RIANG. He, along with some of my old friends and I, still get together for lunch about once a year when I return to the East Coast to visit family. I can’t talk about people in the RI Air Guard who had a major impact on me without mentioning Col. George F. Remington III, our Deputy Commander for Maintenance (now referred to as Maintenance Group Commander), who was an all-around nice guy, pilot extraordinaire, and great commander, may he Rest in Peace. He was another great guy who really looked out for and took care of his troops. One year, he refinished a vintage snow sled to like new condition and gave it to me for my three kids to go sledding in winter. Then there was our Safety Officer, LtCol Rod Taylor, who I really liked a great deal. One evening, when I was working late to support night flying, he asked me if I wanted to go for a ride to McGuire AFB and back in one of our C-119s. Of course, I jumped all over that, and he let me ride the right seat down and back. Rod was a great guy, and I’ll always remember him as one of the most down-to-earth guys I’d ever met in the military. There are so many more, but I did enjoy my association with the men and women of the 143d during the 12 years I was with the unit.

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

I keep in touch with a lot of the guys from my days with the 31st TFW in Vietnam, and although many of them have passed on, some of them still keep in touch via email or phone. Terry Roberts calls every so often to make sure I’m still kicking, and we have a network of guys who keep in touch via email. I talk with Bill Kranig, Larry Letke, Fred Angst, and a few others every so often, and most of us at least touch base periodically via email. Every couple of years, a bunch of us get together for a reunion, and we generally get 60-70 attendees, not counting spouses. That venue has allowed us to reconnect with a lot of guys, including ones we didn’t know at the time but have met since coming home and attending the reunions. I managed to reconnect with some of the guys I knew well but had lost touch with over the years because of the reunions. Dale Brown, who started this whole thing, deserves a lot of thanks for what he has done to bring us all together, and much thanks and gratitude to all the other folks on the reunion committee who put together a wonderful event every two years. Two of the key committee members have recently passed, sadly, and based on all of our advancing ages, with most of us ranging in age from our mid-70s to 90s, it looks like we’ll be having reunions every year from now on until we’re no longer able, instead of holding the reunions every two years. I was very good friends with J.C Weller while both of us were based together in Vietnam and the Philippines, but I lost touch at one point for a number of years. Due to the wonders of the interwebs and the Tuy Hoa reunion web page, we reconnected and made a point of getting together every year from then on. We often spoke over the phone, rehashing old times and talking about old shenanigans and other things we had been involved with in life since being stationed together. He dropped me off at the DC train station ten years ago following a drive back from one of our reunions in Dayton, Ohio, in 2013; that was the last time I saw him. His daughter called me a couple of months later to tell me he’d passed from complications of pneumonia.

Rest in Peace, J.C. Weller. John and I pulled some crazy shenanigans in the Philippines. In those days, military pay was definitely not the best, and guys were always looking to supplement their rather meager incomes, and we were no exception. Sneaking our monthly ration of American cigarettes off the base and selling them on the black market was pretty much routine. JC, at one point, even opened his own bar in Angeles City, which he operated with his girlfriend, Dory. He called it JD’s BFD! The JD was for John and Dory, and you can guess what the BFD stood for. Besides Terry Roberts and J.C. Weller, there was Bill Hill (may he also rest in peace), Keith Knowlton, Fred Angst, Jim Brubaker, Bill Kranig, Dennis Bebak (may he also rest in peace), Curley Campbell (may he too rest in peace), John Birch, Bill Sauber, Larry Letke, Rick Bender, Rusty Gadberry, Dave Bailey, and so many more. Every time we get together, it seems like no time has passed since the last reunion.

Although I still keep in touch with many guys from my days in Vietnam, I’ve managed to stay in touch with one guy from my unit at Clark, Bill Nagy, who I accidentally stumbled across when he was based with the Tennessee Air Guard in Nashville. Unfortunately, I have not yet been able to reconnect with anyone from McGuire AFB. I’d dearly love to find and reconnect with John Sarver or any of the other guys from my old shop at Clark Air Base, like Charles W. Dugan or Samuel M. Wickline, Sam Schmerbach, and a few others. Besides my old shop chief at McGuire, I only remember Ross Ensor, another guy we called Noogies, and Jose Medina-Gonzalez, and that’s about it, other than the guy who gave up his Air Force career to avoid taking an assignment to Thule, Greenland. I can’t remember his name.

The RI Air Guard is a different story: I remember all of those guys, and despite almost 40 years after I transferred out, many of us stay in touch in large part through email, FB, and annual get-togethers, or at least whenever I get back to New England to visit family.

The same holds true with the California Air Guard at March ARB – it’s been 20 years since my retirement, but many of the old Guard folks get together periodically for lunch or reunions, and I hang out with some of them from time to time, mainly CMS Bruce Garcia (retired) – we share a common interest in vintage cars and trucks as well as having worked together in various capacities for 19 years. Even today, I work with some of my former California Air Guard co-workers as fellow contractors in Transient Alert, like Harold Frazier and Chris Cholewiak. Former Weapons and Phase Dock Chief Art Carpenter worked with us for a while before bailing out of the People’s Republik of Kalifornia and moving to Arizona. Co-workers, brothers-in-arms, whatever you want to call us, we often maintain lifelong connections, and it is difficult to explain the concept to civilians.

Can you recount a particular incident from your service, which may or may not have been funny at the time, but still makes you laugh?

I recall one incident on a TDY to Rhein-Main Air Base in Germany, I believe sometime around 1978, where we in the Rhode Island Air Guard partnered up with the Delaware Air Guard on an exercise. I was hanging out with one of the guys in our Hydraulic Shop, TSgt Theodore (aka Teddy) Council. May he rest in peace. We’d gone to midnight chow after having consumed probably a few too many alcoholic beverages, and on the way out the door after finishing chow, Teddy and I thought it might be funny to abscond with the dining facility’s welcome mat. The name of the place was the Zeppelin Inn, and the red and black doormat had a very nice logo that we thought might look great hanging on the wall back home in our joint Airmen, NCO, and Officer’s Club, so we rolled it up and off we went with our plunder. Unfortunately for our club and for us, we were observed in the middle of the ill-planned deed by some observant sky cops who promptly detained us and hauled us off to the local hoosegow on base. Our detachment commander was the DCM from the Delaware ANG, and to our incredible embarrassment, he was called out to come retrieve us. I should mention that since he was awakened from his night’s sleep to bail us out, he was not a very happy camper. We took our chewing out with grace and moved on but privately got a good laugh out of the deal.

Approximately a year or two later, we were TDY to Howard Air Force Base in Panama on a Volant Oak Deployment. This ongoing operation entailed two Air Guard or Reserve units on station at any one time, with units overlapping in a leapfrog type replacement so there would always be a one-week overlapping continuity of operations between units. The Delaware Air Guard was due in the week after we arrived to replace the unit just before us, and very coincidentally, Teddy Council and I were on that same deployment. And just by pure coincidence, we learned that the Delaware Air Guard DCM who bailed us out of the hoosegow in Germany was again coming in to be the Detachment Commander in Panama. Teddy and I came up with the brilliant plan to round up a red carpet doormat somewhere in order to roll it out and greet our old friend, the Delaware ANG DCM, at the aircraft upon arrival. Somewhere on Howard AFB, we found an appropriate red carpet to use for our little welcoming joke, and after the Delaware C-130 landed, we waited for the Colonel to deplane. At that point, we stepped in and rolled out the red carpet for him and gave him a hearty welcome. Of course, he remembered us from the incident in Germany and got quite a good laugh at our latest stunt. We all laughed about that for years afterward.

What profession did you follow after your military service, and what are you doing now? If you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

Having served a total of 37 years, all of it in various disciplines of, mostly all, military aircraft maintenance, my plan was to just retire and travel the globe with my wife. Life doesn’t always work out as planned, and mine was no exception. My wife passed away due to cancer in 1999, and that completely changed everything. It was a very difficult period in my life, and I was devastated. There were many low points where I really didn’t care if I made it through the week or not, but I eventually got through the grief and remarried. Since my current spouse is somewhat younger than I, and since she is still working, we aren’t going anywhere quite yet, so very shortly after I retired, I ended up taking a job as a contractor working in Transient Alert (T/A) at March ARB. In T/A, we handle all visiting aircraft not assigned to March, which is a pretty decent job for a retired aircraft maintenance guy as it doesn’t require a whole lot of heavy work or getting one’s hands into the nitty-gritty. Most of my workload comprises parking, servicing, and launching, visiting aircraft, coordinating parts and equipment when and where needed, and other logistics as needed. Working Transient Alert is a nice fit and continuation for a lifelong career in the aircraft maintenance business. I expect to hang it up sometime in the next year or two, but for now, it keeps me going and keeps me in spare change for stuff I probably don’t really need. Until the time comes that my spouse pulls the plug and we can move elsewhere, I’ll likely continue to work at least part-time until we decide what to do next.

What military associations are you a member of, if any? What specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

I’m a life member of the VFW post in Moreno Valley, CA, although I must admit that I rarely attend any of the meetings. I’m also a member of the American Legion Post in Norco, CA, a life member of the Vietnam Veterans of America Chapter 47 in Riverside, CA, and a Life Member of the Inland Empire Chapter of Combat Veterans Motorcycle Association Chapter 33-3 currently based out of the American Legion Post in Norco, CA. I’m most active with CVMA and have been for the past 15 years, as we do a fair amount of riding together as a group, as well as doing what we can to help other veterans. Our motto is “Vets Helping Vets,” and we do a pretty good job of living up to that motto. The group is comprised of vets from Vietnam all the way through Iraq and Afghanistan and a myriad of other combat operations who like to ride motorcycles. Like the other major veterans organizations, we have chapters in every single state as well as some overseas chapters. In the photo, you can see several members of our local chapter pictured at Independence Pass in Colorado on our way to the annual National Meeting. We took three days to ride up, a day and a half there in Colorado Springs, and three days to ride back. Such a trip builds camaraderie just as it did in our military days. I’m the oldest rider in the group, on the left.

I also recently joined American Legion Riders out of Hemet, CA, in the summer of 2022, out of the urging of a former Army Ranger friend who is quite active with the American Legion and the ALR. Due to my more active role in CVMA, I don’t see myself being able to be quite as involved with ALR as I am with CVMA. Veteran motorcycle rider groups excel at giving back to the veteran community, and I’m proud to be associated with both CVMA and ALR. One of the primary recipients of our support is the Veterans Village operated by US Vets on part of former March AFB land. We support them with regular food donations to their pantry and occasional barbecues for the residents.

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

Serving in the military has left me with a very good sense of camaraderie with my fellow veterans, along with a feeling of pride in our country despite some of the incredibly stupid decisions by incompetent and corrupt career politicians that have directly resulted in injuries and deaths to our servicemen and women. Despite the incompetence of a very corrupt political class in this country, I wouldn’t trade my time in service for anything. I was a very shy kid, but working my way up through the ranks over the years helped instill confidence in me over time and has developed in me an attitude of “service over self,” which has managed to grow over time. Service over self gives me a purpose in life beyond just meandering through life from week to week, month to month, or year to year. All of that I attribute to various people I’ve encountered and worked with over the years, and I feel truly blessed to have known and worked with the people I’ve been associated with since that first day I stepped into the arena at Lackland AFB on October 20, 1967, until the day they kicked me out the door at March Field in October 2004. Opportunities to travel and see the world as part of a team effort to set up and accomplish a mission in unusual environments are what I miss the most. The bonds that military people forge, for the most part, stick with us forever because we engaged in and overcame challenges through team effort, sometimes in less-than-desirable or outright hostile circumstances. There are literally dozens if not hundreds, of photos I could use to illustrate that point, but I chose this particular photo because it shows every single person from my old 163rd Avionics Photo-Sensor Shop, with not one single person missing. In the photo, you can see us all with some of our aircraft equipment laid out in front of one of our RF-4C reconnaissance jets sometime around 1992, just before we split up and converted to KC-135 Tankers. We were a very close-knit shop and continued to have Sensor Shop reunions periodically for several years afterward, and some of us still stay in touch some 30 years later. That’s the kind of camaraderie the military builds and always has helped to build.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Air Force?

Opportunity and having options to grab an opportunity are a huge part of Air Force life that most civilians never get a chance to take. Being a part of the Air Force spanning five separate decades from the 1960s through the 2000s and even beyond that as a contractor, I’ve had the good fortune to have had a number of opportunities presented to me that, in some cases, I took, others I did not, much to my regret. Over the years, we’ve seen incredible changes take place, many for the better, some not so much. We’ve seen modern and very technologically advanced aircraft entering the inventory, incredible advances in flight safety, women having opportunities to enter jobs previously closed to them, and seeing pay and benefits finally coming on par with civilian employment, so my advice for young airmen is take advantage of the incredible opportunities presented to you in today’s modern Air Force, and take advantage of the educational opportunities the GI Bill has to offer. As the old adage goes, nothing ventured, nothing gained. A key piece of your career is to plan early for retirement – it’ll be on top of you before you know what hit you. Treat everyone with respect and do your job to the very best of your ability.

Most importantly, do not be a “that’s not my job” type. Lend a hand wherever it’s needed, and be consistent and positive in everything you do. It’ll be difficult at times, but a consistently positive attitude and can-do approach to everything you do will serve you well throughout your career.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with.

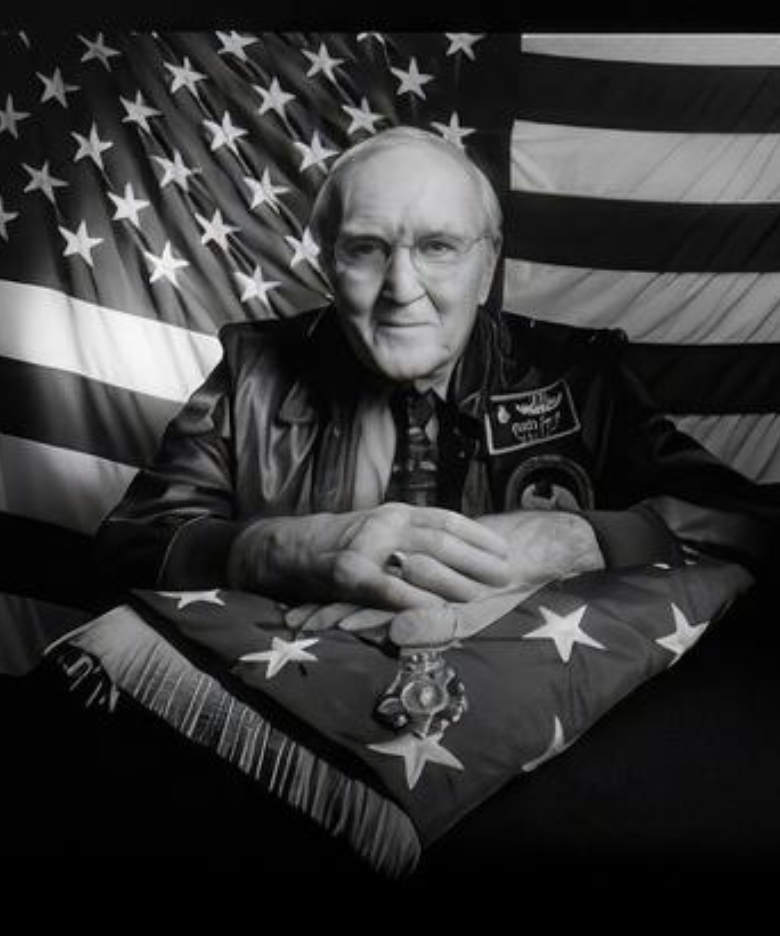

I have been a member of TWS for several years and have enjoyed participating in it and making new connections. Completing the various blocks or sections that help highlight and outline my career has helped me recall many forgotten experiences. I could probably add lots more, but at this point, I do realize I’ve rambled on far more than I intended, and if you’ve gotten this far, I commend your endurance! TWS has helped me recall former squadron mates and good friends who made my memories and experiences what they are today. It’s also part of a life story I wanted to leave to my kids and grandkids, and the format that TWS has laid out for all of us has made it all that much easier to accomplish. Early on, I really had no plans to complete this Service Reflections portion of the website as I really didn’t want to share my story. As I write this last section, I’m still debating whether or not to follow through and actually publish it for others to read, but if you’re reading this, then I obviously decided to follow through. I must admit that after having read other people’s stories, I found most of them quite fascinating, much more so than my own. I know we can’t all be a Chuck Yeager, a Robin Olds, a Carl Spaatz, a Hap Arnold, a Chappie James, or a Guy Gruters, but we all have a story to tell, and we’ve all contributed to the strength of this nation and its Air Force in one way or another. I really wanted to mention Guy Gruters – I’m standing next to him on his right at our last Tuy Hoa Air Base reunion in 2023 in Colorado Springs – he’s pictured in the black suit in this photo. He endured over five years of unimaginable horror as a POW in North Vietnam, and he was a featured guest speaker at two of our Tuy Hoa Air Base reunions over the years. He was a former Misty FAC pilot, a group I talked about in an earlier segment. The story of his experiences and his life is hard to comprehend for most people, but he, like the rest of us, has a story to tell. You can look him up on the internet and read about him, but it barely touches the depth of what he endured. His story is far more incredible and considerably more impactful than most, but it is one of many stories that make up the Air Force story. TWS plays an important role in helping us put it all together. Thank you, TWS!

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

0 Comments