The guerrilla war was not going well for the Viet Cong in the late fifties. Badly needed supplies moving down jungle trails from North Vietnam were constantly being spotted by South Vietnamese warplanes and often destroyed. To give themselves a fighting chance, existing tribal trails through Laos and Cambodia were opened up in 1959. The North Vietnamese went to great lengths to keep this new set of interconnecting trails secret.

America’s Secret War Begins in the Jungles of Laos

The first North Vietnamese sent down the existing tribal trails carried no identification and used captured French weapons. But the Communists could not keep their supply route secret for very long. Within months, CIA agents and their Laotian mercenaries were watching the movement from deep within the hidden jungle.

But keeping an eye on what the North Vietnamese were doing in Laos was not enough for Washington.

They wanted to put boots on the ground in a reconnaissance role to observe, first hand, the enemy logistical system known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail (the Truong Son Road to the North Vietnamese).

By late, 1964 South Vietnamese recon units were inserted into Laos in ‘Operation Leaping Lena.’ After a number of disastrous missions, it was determined U.S. troops were necessary, and Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) was given the green light to take over the operation.

America’s Secret War Expands with MACV-SOG Operations

Thus was born the secret war in Laos that would eventually kill about 300 hundred Special Forces troops, with fifty-seven Missing in Action, and some fifteen known to have been captured. But the Communists never admitted to having captured any Special Forces troops. In November, the first American-led insertion was launched against target Alpha-1, a suspected truck terminus on Laotian Route 165, fifteen-miles inside Laos. A newly formed reconnaissance team selected for the initial mission was Recon Team (RT) Iowa.

The team leader was Master Sergeant Charles Petry along with Sergeant First Class Willie Card, a South Vietnamese Army Lieutenant and five Nungs (fierce fighters of Chinese decent used extensively and paid by U.S. Special Forces). They were the first U.S.-led cross-border secret operation into Laos, code-named ‘Shining Brass,’ to reconnoiter and interdict infiltration along Ho Chi Minh Trail.

The Special Forces officer supervising the mission was Capt. Larry Thorne, the subject of last month’s Dispatches article “Three Wars under Three Flags.”

It was the rainy season in Vietnam, and RT Iowa prowled the Special Forces camp at Kham Duc, near the Laotian border, waiting for the rain to let up and for the clouds to break.

Tension during the idle days ran high, for their highly classified mission could open a new phase of the war. Finally, the rain stopped, but visibility was still poor on the Laotian border to the West, where mountain peaks poked above the clouds. It was finally agreed, however, to try and infiltration despite the unfavorable flying conditions.

Hence, toward the end of the third day, October 18, 1965, two South Vietnamese operated CH-34 helicopters unmarked and sprayed with camouflage paint, lifted off, and climbed above the clouds over Kham Duc and banked to the West toward a suspected truck park 15 miles inside Laos.

Recon Team Iowa members set on the floor of the lead chopper. Dressed in camouflage fatigues and soft bush hats or rags tied around their heads, they carried no identification, and all their gear and weapons were ‘sterilized’ – non-U.S. government issue. This was a highly secret mission the United States did not want to be traced back to the American forces.

America’s Secret War Claims Lives and Reveals Its Hidden Cost

Thorne was the only American passenger aboard the South Vietnam Air Force flown command and control aircraft. U.S. Army Huey gunships launched at the same time to provide air cover should it be needed at any time during the mission.

As the CH-34s and Huey gunships flew low over the countryside, all they could see were rolling hills, wild rivers, and waterfalls. The weather proved especially hazardous, forcing them to weave between thunderheads and sunbeams while avoiding sporadic .50 caliber machinegun fire, all of which missed.

The flight arrived over the target area just before sundown. All aircraft circled the area looking for a way to get down to the clearing through the thick angry clouds that blanketed the area. A decent seemed hopeless, and darkness was closing in. Minutes before Thorne intended to cancel the mission and return to Kham Duc; the clouds opened up slightly, allowing the CH-34 carrying RT Iowa to spiral into the slash-and-burn clearing, rapidly discharge its passengers and immediately climb for altitude. As Thorne’s helicopter attempted to descend, the clouds again closed up. Thorne ordered the now empty CH-34 to return to Kham Duc.

As the weather worsened, Thorne continued to orbit near the landing zone in case RT Iowa ran into trouble. After received a message from the team that their insertion was successful, he transmitted that his aircraft was also on its way back. Approximately 5 minutes after receiving the patrol’s report, the other aircrews heard a constant keying of a radio for roughly 30 seconds. After that, only silence was heard in response to repeated attempts to raise anyone aboard Thorne’s helicopter.

The disappearance of Thorne’s aircraft and Vietnamese crewmen, without so much as a radio distress call, was never explained, nor was any wreckage found after days of trying. Operation 35 had claimed its first victims, and a shot had yet to be fired.

After three days on the ground, deep behind enemy lines, the seven-man patrol ran into a heavily defended enemy ammunition dump. One team member was killed. The rest withdrew to a hill, called in tactical air, and within minutes, bombs were destroying the enemy’s precious ammunition. The team was extracted without further incident.

For the next five years, Special Forces led patrols scouted the Ho Chi Minh Trail on a regular basis and fought the North Vietnamese they found there. The Ho Chi Minh Trail was no longer a mystery, and ultimately became a killing ground for many of the North Vietnamese who worked there, or were just passing through.

During those five years, the cross-border operations in Laos were active; it changed names three times; “Operation Shining Brass” was renamed “Operation Prairie Fire” in 1968 and finally, “Operation Phu Dung” in April 1971. But whatever name it went by, countering NVA infiltration through Laos into South Vietnam became the largest and most important Special Forces strategic reconnaissance and interdiction campaign in Southeast Asia.

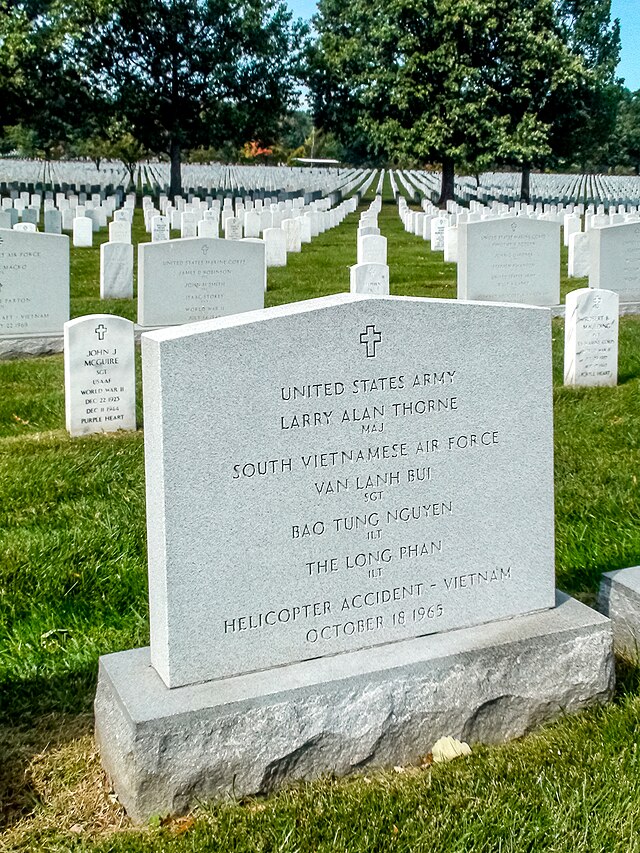

In 1999, Thorne’s remains were found by a Finnish and Joint Task Force-Full Accounting team that was excavating a helicopter crash site near Thorne’s last suspected location. DNA on remains found at the site were those of Thorne and the South Vietnamese airmen. He was buried on June 26, 2003, at Arlington National Cemetery, section 60, tombstone 8136, along with the Vietnam casualties of the mission recovered at the crash site.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the America’s Secret War, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

My husband was in the army drafted in 1972 and was in special forces . He was In This group. He passed away from cancer in 2019. I am trying to find his dd214 forms and I am having a very difficult time locating them . Can you help me?

One of the photos shows the NVA/VC carrying weapons and supplies down the Ho Chi Minh trail on bicycles. My US Army Special Forces A-Team in 1968 had a camp (A-322 Katum) just a few klicks from the Cambodian Border in Tay Ninh Province and along the Ho Ch Minh trail in RVN. One night, two Special Forces men with a company of CIDG, out in the jungle heard some noises. Sounded like trucks but they were not sure, They called for an aircraft that had a LARGE searchlight. The plane arrived and turned on the light. NVA 2.5 ton trucks shone in the light. The trucks were attacked with small arms and artillery etc.

In 1970 I was with MACVSOG running recon missions out of Da Nang. On a mission in Laos we found an NVA Truck Stop with a guard in a guard shack in uniform with a pith helmet and many trucks, parked. A helicopter strike came in and shot up the area with rockets and machine guns. We silently crept away.

When I got back to the States, the news was still showing pictures of poor VC villagers bringing supplies to South Vietnam on bicycles.