Keith Saliba’s book’s real-life setting is an isolated, heavily fortified frontier outpost In Vietnam’s West-Central Highlands near the Cambodian border and the Ho Chi Minh trail, the main conduit for troops and supplies from North Vietnam.

“It was a 20th-century version of the Wild West frontier fortress,” Saliba said, in territory Army Special Forces soldiers called “Indian Country”-remote, dangerous.

In October 1965, the camp at Plei Me was guarded by a 12-man American Army Special Forces “A-Team,” along with Montagnard fighters native to the region and a small contingent of South Vietnamese Special Forces soldiers.

But by Oct. 19, almost 2,000 North Vietnamese soldiers had crept into position around Plei Me. An equal number were deployed to ambush any relief force sent to the camp’s rescue.

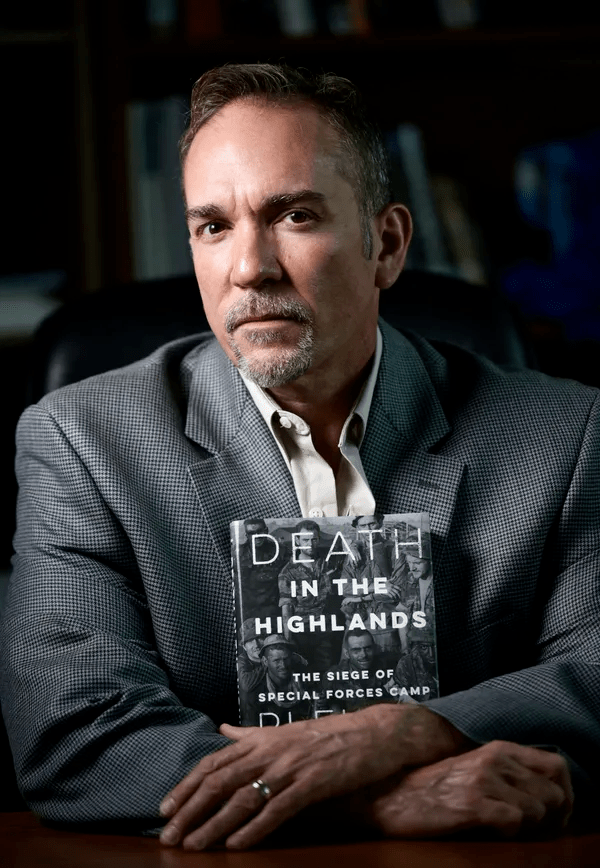

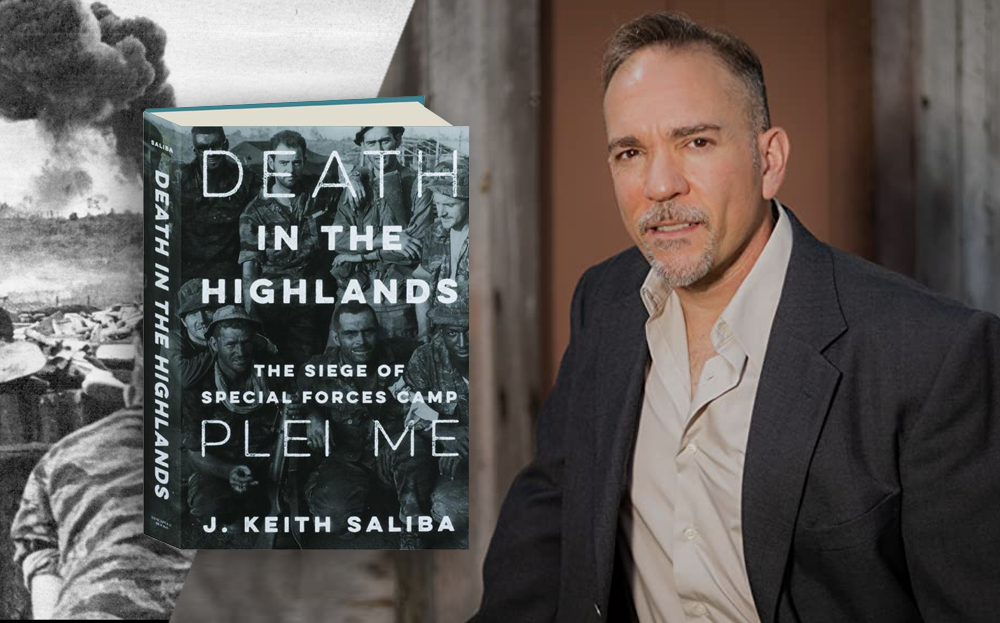

And so begins the battle he describes in “Death in the Highlands: The Siege of Special Forces Camp Plei Me.”

Vastly outnumbered, the Special Forces soldiers fought back with their Vietnamese allies in an ultimately successful, week-long battle that involved vast amounts of close air support and daring air resupply missions.

Saliba, a former journalist, is an associate professor of journalism and mass communication at Jacksonville University. One of the men he interviewed for the book was Euell White, 86, who retired from the Army as a major and lives in Florence, Ala.

In October 1965, White was a 31-year-old first lieutenant in Project DELTA, a clandestine Special Forces reconnaissance unit. He was among those who joined in the rescue attempt at Plei Me, during which he was wounded in a ferocious firefight – an experience Saliba describes in harrowing detail.

He praised Saliba’s book.”It was really educational for me because I didn’t know about the background, the build-up to Plei Me,” White said. “He did all that research.”

But White said he knew the risk he was taking heading to Plei Me.

“I knew it was going to be bad out there, and when I got wounded and left alone for a time, my chances of getting out of there looked pretty slim to me,” White said.

So what motivated him?

“It was a Special Forces team, under siege,” White said. “We always tried to look after our own. From the time I enlisted in the Army in 1951, it was part of being a soldier.”

Saliba said he found that same sentiment in his research.

“The response I got from both the guys on the ground and the guys in the air was: They would do it for us. They needed us, and so we were going to be there for them. That was our job, that is what we were going to do, to do whatever we could to help them.”

Saliba has written about Vietnam for some 20 years, even though at 53, he is far too young to have fought in it-or even to be that aware of it while it was going on.

He said the tragedy and heroism of the war is what drew him to it and kept him interested in exploring it.

“My generation, those kids who came up in the ’80s, were maybe the first ones to see that the Vietnam vets were not well-treated,” he said. “It was almost like a dirty secret. It always rubbed me the wrong way.”

As a young journalist in Albany, Ga., he interviewed a veteran of the battle at la Drang, which was told in the 2002 movie “We Were Soldiers,” starring Mel Gibson. It took place just weeks after the siege of Plei Me, which is considered the prelude to that clash.

While the veteran, unhappy with how Vietnam vets had been portrayed, was initially reluctant to speak, he eventually told his story to the reporter. And he and Saliba became friends.

“Hopefully, I fulfilled my pledge to be respectful and, at the same time, tell the story,” Saliba said.

The Subject of Death In The Highlands

La Drang was the subject of Death In The Highlands by war correspondent Joe Galloway, on which the Mel Gibson movie was based. Saliba interviewed Galloway about Ple Me, and Galloway gave him a nice cover blurb for his book, saying, “This story has it all, Keith Saliba has done them all proud.”

In graduate school, Saliba’s master’s thesis was on Esquire magazine’s coverage of Vietnam, from writers such as Michael Herr (“Dispatches”) and John Sack.

He’s since contributed to a series of books on the war and has researched the psychological effects of the 1969 Tet Offensive.

Saliba said he’s thinking of next tackling a book on the rise of fall of ISIS in the Middle East. But he’s not likely done with Vietnam.

“There were so many different layers, so much nuance. It was just fascinating. And obviously, the longer you pay attention to something, the more comfortable you feel about writing about it,” he said. “Vietnam always keeps calling me back.”

I think the article has the year wrong in the paragraph “The Subject of Death in the Highlands”. It was actually the 1968 Tet Offensive.