In the summer of 1864, the Confederate States of America was reeling from a series of defeats that would ultimately lead to its demise. Despite the Union victory at Gettysburg in 1863 that turned the Army of Northern Virginia back and the capture of Vicksburg that gave the Union control of the Mississippi River, the outcome of the Civil War was anything but assured.

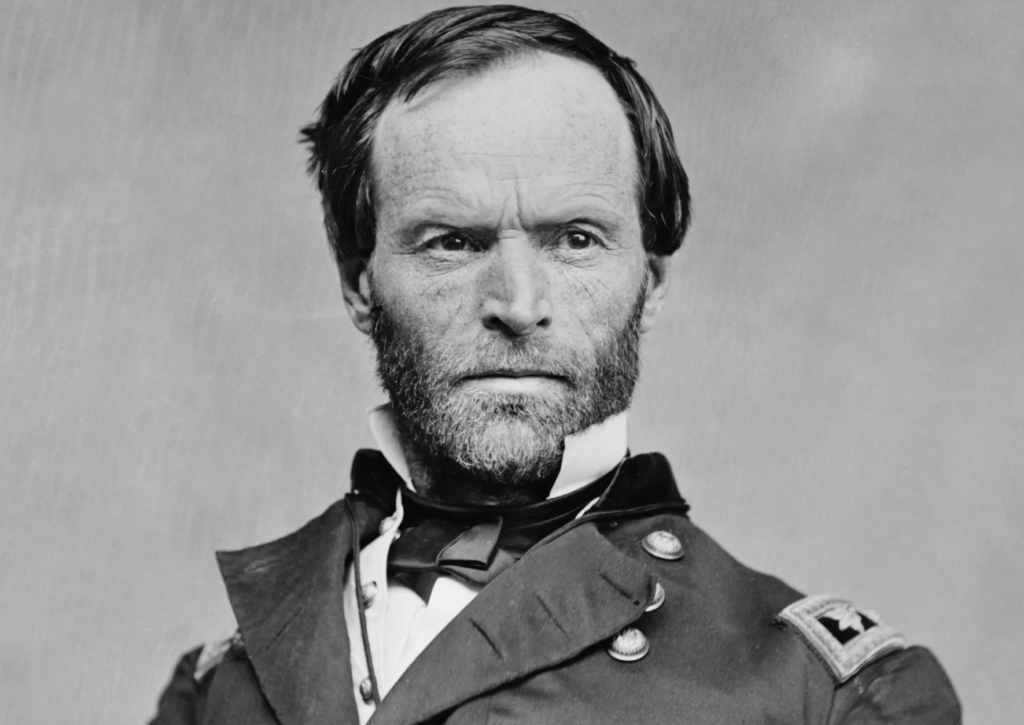

After leading the Union Army at the Siege of Vicksburg and his subsequent win at Chattanooga, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to Lieutenant General and given overall command of the Union Armies. With the Confederacy now split in two, Grant took over command of the Army of the Potomac while command of the Western Theater fell to Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman.

In the spring of 1864, Grant decided to launch simultaneous offensives all along the Confederate lines in an effort to exhaust the Confederacy’s resources and its ability to prolong the war. For Sherman, this meant engaging Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s Army, which protected Atlanta, the south’s largest industrial and logistical center.

It was also the largest administrative area for the south, outside of Richmond. While Grant launched his Overland Campaign against the Confederate capital, Sherman headed for Atlanta, where four major railroads connected the Confederacy.

Johnston knew Sherman’s relatively massive Army outnumbered him and retreated time and again when Sherman outflanked his defenses. Tired of his retreating, Confederate leaders replaced him with Gen. John Bell Hood, who immediately went on the offensive. At Peach Tree Creek on Jul. 20, 1864, the Confederates attacked but found Johnston was right. The assault failed, costing Hood casualties he couldn’t afford.

One Chance to Win the Battle for Atlanta

On Jul. 21, Sherman gave Hood one chance to win the battle for Atlanta and perhaps the entire Confederacy. Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s Army of Tennessee was positioned on the city’s outskirts to the east, but his left flank was open while Union cavalry wreaked havoc on the southern railroads.

Hood saw his chance to march a corps of infantry, and Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry around the Union Army’s left flank attacked Sherman’s supply line, similar to a move that led to Stonewall Jackson’s victory at Chancellorsville, Virginia, earlier in the war.

Wheeler was to attack McPherson’s supplies while Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s corps attacked his left rear. It required a 15-mile night march to launch a daring dawn attack. However, the night was hotter than expected, and the Confederate soldiers were exhausted from the maneuver. It wasn’t until noon the next day that the rebels were ready to deploy.

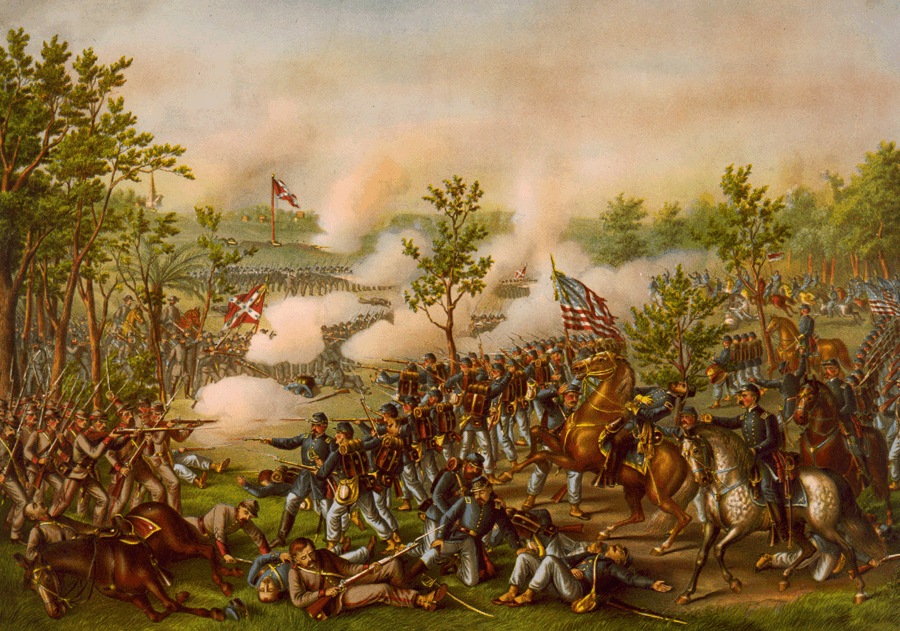

Meanwhile, McPherson noticed his left flank was vulnerable during the night and sent his reserve to defend it. When the rebels launched their “surprise” attack that afternoon, they weren’t fighting a baggage train; they were fighting a battle-hardened and fortified infantry.

McPherson left Sherman’s headquarters and made his way to watch the fighting when he was shot by Confederate infantry under Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne. With the General dead, the Confederates began turning the left flank of the Union line and start to overrun it.

More luck for the rebels came in nearby Decatur, where Wheeler’s cavalry captured the Fayetteville Road and forced the Union to abandon the town. The fleeing Yankees were barely able to save their supply wagons. But while the initial success was heartening, it soon turned into a disaster for the rebels.

Hardee’s infantry on Sherman’s left flank may have overrun their enemy at first, but they ran right into infantry and artillery fortified from a nearby hilltop. Unable to dislodge them or advance, Hardee is forced back. Without the infantry’s support, Wheeler was forced to abandon Decatur.

The surprise may have failed, but the battle of Atlanta wasn’t over. Cheatham’s corps attacked the main Union force from the east, centered on nearby Bald Hill. The fighting on Bald Hill was brutal and sometimes hand-to-hand, but Cheatham attacked the Union Army in a series of uncoordinated assaults. The rebels also saw success there, but superior Union artillery and a counter-attack forced them back into the city.

How the Battle Ended?

Sherman’s Army settled into a siege. After unsuccessfully trying to cut off its supplies for a month using cavalry raids, he cut the railroad lifeline using his entire Army. It forced the Confederates under Hood to abandon Atlanta. The city fell to the Union on Sept. 2, 1864. On Nov. 12, Sherman ordered the city’s business district destroyed before departing for his famous “March to the Sea.”

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the Battle of Atlanta, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

I am related to MajGen McPherson on my mother’s side of the family.