After the successful siege of Fort Henry by Federal troops on February 6th, 1862, the Confederate forces hurried back to the neighboring Fort Donelson, which was located a few miles away.

The Federals sought control over the waterways of Cumberland and Tennessee, knowing full well the advantage that it would afford them in the Western Theater of the Civil War.

The chief agitator of the move to conquer the forts was Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who had sent several telegrams to his superior officer, Maj. Gen. Henry Wager Halleck.

In his messages, he urged Halleck to deliver his consent to besiege the forts along the Cumberland and Tennessee waterways, all without favorable response.

Despite being a very successful commander in the Civil War, Halleck had little faith in Grant, fearing him to be very irrational in his thinking. Once Grant’s requests were backed up by Flag Officer, A.H. Foote, the petitions made by Grant were accepted.

Nonetheless, Grant wasted no time in producing results by capturing Fort Henry five days after he was given the order to proceed with the assault and sustaining only as little as 40 casualties. The next line of action was, therefore, to obtain control of the other Confederate fort that overlooked the waterways.

Taking a few days off to prepare a strategic assault for which he reported his intent to take Fort Donelson on February 8th, whereas Halleck’s initial orders were to ‘take Fort Henry and return.’ More formidable than Fort Henry, Grant expected to fight a greater battle at Fort Donelson if he was going to gain control and drive out the Confederate soldiers occupying it.

This was the last major obstacle preventing the control of the rivers that led into Tennessee and Missouri, and Grant was poised to besiege and overcome it.

About the Fort Donelson and the Fort Henry

Fort Donelson stood near the Tennessee-Kentucky border as a bastion-type fortification with two batteries and at 100 ft. above sea level, the fort allowed its defenders the ability to engage in plunging fire, thus covering a longer distance of fire as well giving trajectory angles against attacking gunboats.

In this regard, Fort Donelson established superiority over Fort Henry as well as having a better location. It was named after Brig. Gen. Daniel Smith Donelson of the Confederate Army who gave approval for its construction as well as Fort Henry.

The fort boasted a 10-inch columbiad, still in frequent use at the time for heavy direct and projectile shooting at low and high trajectories. Also, in the artillery were two 32-pound Carronades, nine 32-pounders, and a rifled gun.

When Gen. Albert Sydney Johnston learned of the fall of Fort Henry into Federal hands, he immediately sent reinforcements of 12,000 men to solidify the defenses at Fort Donelson.

However, fearing that the fall of the second fort was only a matter of time, Johnston moved his army to the Tennessee capital of Nashville.

Prior to the arrival of the reinforcements, the combined forces of the survivors of Fort Henry and the army present at Fort Donelson numbered a total of 6,000 men under the command of Brig. Gen. Bushrod R. Johnson.

The arriving reinforcements were under the command of Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd, a man who was more of a politician than a soldier. Many historians have criticized Johnson’s choice of Floyd as commanding officer at the fort from among his array of senior Officers.

Floyd lived up to his reputation by subsequently relegating his military duties to Brigadier Generals Simon B. Buckner and Gideon J. Pillow. In Grant’s account of the battle, he described Floyd as unfit for the command which he was entrusted.

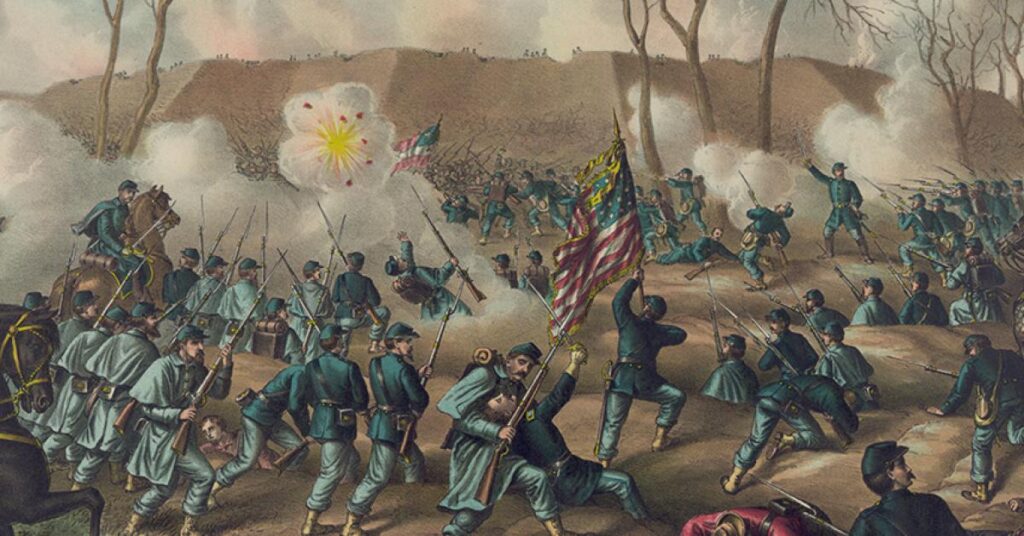

The Beginning of Hostilities

Hostilities commenced on February 12th, 1862, with the Confederate forces still setting up entrenchments around the fort, Brig. Gen. John A. McClernard of the Union Army began the battle in a skirmish with Lt. Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Cavalry.

Arriving later that day, Grant established his headquarters at the Widow Crisp’s house. The Federals slogged at the earthworks of the Confederates for days, engaging in artillery duels and frequent skirmishes.

On one such occasion, on the Friday of February 14th, Flag-Officer Foote, leading a naval assault of the Flag-ship St. Louis with three ironclads undertook heavy attack which left the flag-ship wrecked along with one of the ironclads and two boats, leading to the deaths of 55 Federals, some of whom were Officers. Foote was injured, ironically on his foot.

After trying for several days unsuccessfully to deal a significant blow that would indicate a victory for the Confederates at Fort Donelson, it was only a matter of time before they ran out of supplies and ammunition.

Meanwhile, the Federals spent a few nights out in the winter cold without food; neither army dared to light fires for fear of sharpshooters.

After a council of war meeting organized on the morning of February 15th, Pillow lead a failed attempt to retreat from the fort, they successfully assaulted the Federal lines for hours until about 1:00 PM and had the upper hand to escape.

Pillow then ordered the Confederates to return to the fort to regroup and gather supplies before leaving. This decision would, however, prove costly as it undermined the gained grounds of the morning’s efforts.

When the Confederate Army was stacked up and ready to move out a determined Brig. Gen. Charles F. Smith and Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace’s brigades drove them back into their entrenchments, dashing all hopes of a successful evacuation of the troops.

That night, Floyd, Pillow, and Buckner and some other senior Officers met to determine their next course of action against the Federals.

Buckner believed the only action left to take was to surrender to the Union, something Floyd swore that he would never do, as was Pillow.

Floyd thereafter relieved himself of command, passing his duties on to Pillow, who did the same. Buckner, being next in the line of command assumed the responsibility of the fort, stating that he would rather share the fate of the garrison than abandon them in flight.

And so, the stage was set, that night Floyd sent a telegram to Gen. Johnston stating his lack of faith in his army’s ability to withstand the Federal forces. He escaped at the break of dawn of February 16th.

The Outcome of the Battle of Fort Donelson

The total dead in the the Battle of Fort Donelson numbered close to 1,000, over 12,000 Confederates were captured. Casualties of the Union Army were over 2,000 men. Several water vessels and batteries were destroyed.

Pillow and his units fled via steamboats, and Forrest escaped by land. A few hours later, Buckner sent a letter to Grant proposing terms of a truce.

However, Grant replied, stating that truce would only be agreed upon with terms of an unconditional surrender, which Buckner reluctantly agreed to.

White flags were raised, and Grant had succeeded in gaining a strategic victory for the Union, one which merited him the nickname “Unconditional Surrender” and saw his appointment as Maj. Gen. by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln under recommendation from Halleck.

The site of the battle has been preserved by the National Park Service as Fort Donelson National Battlefield. The Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) and its partners have acquired and preserved 368 acres of the battlefield, most of which has been conveyed to the park service and incorporated into the park.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the battle of Fort Donelson, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

0 Comments