Sergeant Dakota L. Meyer is a United States Marine Corps veteran, the recipient of the Medal of Honor and the New York Times best-selling co-author of ‘Into the Fire: A Firsthand Account of the Most Extraordinary Battle in the Afghan War.’ He is also an entrepreneur, having founded a successful construction company in Kentucky.

Dakota Meyer earned his Medal of Honor for his actions during the Battle of Ganjgal in Kunar Province, Afghanistan, as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. He is the first living Marine to have received the medal in 38 years and one of the youngest. Humble and soft-spoken, Meyer insists that he is not a hero, and that any Marine would have done the same thing he did in battle.

Biography of Sgt Dakota Meyer

Born June 26, 1988 and raised in Columbia, Kentucky, he is the son of Felicia Gilliam and Michael Meyer. In 2006, after graduation from Green County High School, he enlisted in the Marine Corps at a recruiting station in Louisville, Kentucky and completed basic training at Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island.

Dakota Meyer deployed to Fallujah, Iraq, in 2007 as a scout sniper with 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines. On his second deployment to Afghanistan with the U.S. Marine/U.S. Army ETT (Embedded Training Team) 2-8, he gained national attention for his heroic actions.

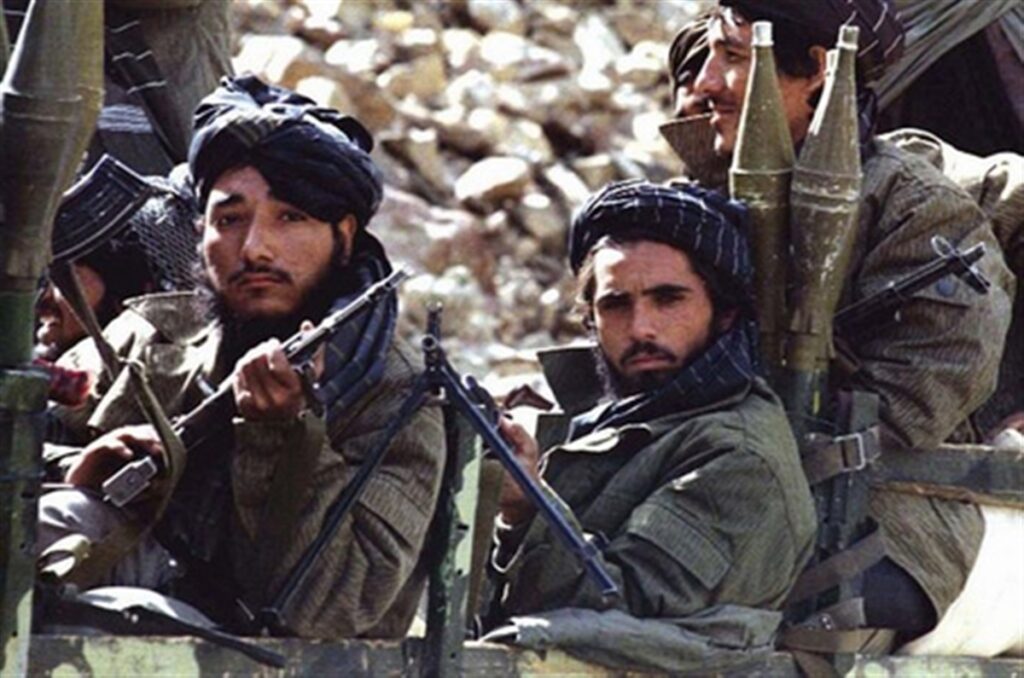

On September 8, 2009, ETT 2-8 led TF (Task Force) Chosin, a combined group of Afghan Army and National Police forces led by a small team of American advisors and trainers, on a patrol operation near Ganjgal village on their way to meet with village elders. TF Chosin had only 3 months earlier closed down a mountainous border smuggling route between Pakistan and Afghanistan, earning additional ire from the Taliban, who controlled the smuggling routes.

During TF Chosin’ s mission planning, it was made clear that no dedicated close air support would be available for the mission but commanders promised artillery support from nearby forward bases. They were promised, however, that helicopter support could be redirected from an operation in a neighboring valley within five minutes. Available intelligence indicated that Taliban fighters were aware of the mission and were setting up ambush positions within Ganjgal village with a forward force of at least 20 fighters.

Just after dawn, after inserting into the valley and approaching Ganjgal, TF Chosin came under heavy machine gun, small arms and RPG fire from at least 100 entrenched Taliban fighters, far more than indicated by intelligence reports. Coalition forces soon found itself pinned down in a deadly three-sided ambush. Initial calls for artillery support were rejected by the command post due to new rules of engagement put in place by Gen. Stanley McChrystal in an effort to reduce civilian casualties. Both an Army artillery NCO and an Air Force Joint terminal attack controller took immediate action to provide the ambushed coalition forces with fire support but were overruled by the command post. ETT 2-8 informed the command post that they were not near the village but were again denied fire support. Calls for emergency helicopter support were also denied because adjacent helicopter assets were tied up and taking fire in support of another operation.

The coalition forces were taking increasing fire and could observe women and children shuttling fresh ammunition to Taliban fighting positions. Within 30 minutes of making contact, the ETT request the command post to provide an artillery barrage of smoke canisters to cover their withdraw. Told that no standard smoke was available, the team requested white phosphorus rounds be used instead to screen their retreat. Nearly an hour later, the white phosphorus rounds landed and the coalition forces retreated under heavy fire a short distance before being pinned once again. By this time, three U.S. Marines, their Navy Corpsman, their Afghan interpreter and several Afghan soldiers had been killed. Taliban snipers were moving into flanking positions when helicopter support finally arrived and began to attack Taliban positions. This arrival allowed the wounded to be pulled out and for three Marines to fight their way back up the hill to retrieve fallen comrades. It was nearly nine hours, including 6 continuous hours of fighting, from initial contact until coalition forces were able to totally disengage from the firefight.

The position occupied by the three dead Marines and the Navy Corpsman had been overrun by the enemy, who stripped the bodies of their gear and weapons. The bodies were recovered after their comrades, including Meyer, braved enemy fire to return to the location.

Dakota Meyer suffered a shrapnel wound in one arm and was sent home after the battle with combat-related stress. The loss of his teammates and friends continued to haunt him for years.

An investigation led U.S. Army Col. Richard Hooker and U.S. Marine Col. James Werth was launched into the lack of requested fire and air support. While members of the task force publicly blamed Gen.McChrystal’s new ROE’s (Rules Of Engagement, as dictated by President Obama), and personnel at the command post agreed, the investigation placed most of the blame on the battalion leadership. It found that three U.S. Army officers at nearby Forward Operating Base Joyce, from Task Force Chosin, a unit comprising soldiers from 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division, out of Fort Drum, N.Y, had exhibited “negligent leadership” which had directly contributed to the loss of life in the battle. Two of the three officers, Maj. Peter Granger and Capt. Aaron Harting were given formal reprimands.

On November 6, 2010-fourteen months after the Battle of Ganjgal-Commandant of the Marine Corps, Gen. James Amos, told reporters during a visit to Camp Pendleton, California that a living Marine had been nominated for the Medal of Honor. Two days later, Marine Corps Times, an independent newspaper covering Marine Corps operations, reported that the unnamed individual was Dakota Meyer, citing anonymous sources. CNN confirmed the story independently two days later.

When the White House staff called Dakota Meyer to set up a time for President Barack Obama to inform him that his Medal of Honor had been approved, they were told Meyer was working at his construction job and were asked to call again during his lunch break.

Meyer Asked if He Could Have a Beer With the President

When Meyer was reached by phone, a White House staffer went over the details of the Medal of Honor ceremony and other particulars. At the end of the conversation, Meyer asked if he could have a beer with the president. That requests was arranged and on the afternoon before the ceremony, President Obama and Meyer, both in shirtsleeves and ties, sat at a metal patio table on the White House lawn, each with a clear glass mug of ale. During their meeting, Meyer requested that his colleagues at the ambush be honored at the ceremony. President Obama agreed.

This is the story of that day, as told by President Obama himself on Sept. 15, 2011, during the Medal of Honor ceremony at the White House.

“Let me tell the story. I want you to imagine it’s September 8, 2009, just before dawn. A patrol of Afghan forces and their American trainers is on foot, making their way up a narrow valley, heading into a village to meet with elders. And suddenly, all over the village, the lights go out. And that’s when it happens. About a mile away, Dakota, who was then a corporal, and Staff Sergeant Juan Rodriguez-Chavez, could hear the ambush over the radio. It was as if the whole valley was exploding. Taliban fighters were unleashing a firestorm from the hills, from the stone houses, even from the local school.

“And soon, the patrol was pinned down, taking ferocious fire from three sides. Men were being wounded and killed, and four Americans – Dakota’s squadmates and friends – were surrounded. Four times, Dakota and Juan asked permission to go in; four times they were denied. It was, they were told, too dangerous. But as one of his former high school teachers once said, ‘When you tell Dakota he can’t do something, he is going to do it.’ And as Dakota said of his trapped teammates, ‘Those were my brothers, and I couldn’t just sit back and watch.’

Dakota Climbed Into the Turret and Manned the Gun

“The story of what Dakota did next will be told for generations. He told Juan they were going in. Juan jumped into a Humvee and took the wheel; Dakota climbed into the turret and manned the gun. They were defying orders, but they were doing what they thought was right. So they drove straight into a killing zone, Dakota’s upper body and head exposed to a blizzard of fire from AK-47s and machine guns, from mortars and rocket-propelled grenades.

“Coming upon wounded Afghan soldiers, Dakota jumped out and loaded each of the wounded into the Humvee, each time exposing himself to all that enemy fire. They turned around and drove those wounded back to safety. Those who were there called it the most intense combat they’d ever seen. Dakota and Juan would have been forgiven for not going back in. But as Dakota says, you don’t leave anyone behind.

“For a second time, they went back – back into the inferno; Juan at the wheel, swerving to avoid the explosions all around them; Dakota up in the turret – when one gun jammed, grabbing another, going through gun after gun. Again they came across wounded Afghans. Again Dakota jumped out, loaded them up and brought them back to safety.

“For a third time, they went back – insurgents running right up to the Humvee, Dakota fighting them off. Up ahead, a group of Americans, some wounded, were desperately trying to escape the bullets raining down. Juan wedged the Humvee right into the line of fire, using the vehicle as a shield. With Dakota on the guns, they helped those Americans back to safety as well.

“For a fourth time, they went back. Dakota was now wounded in the arm. Their vehicle was riddled with bullets and shrapnel. Dakota later confessed, ‘I didn’t think I was going to die. I knew I was.’ But still, they pushed on, finding the wounded, delivering them to safety.

“And then, for a fifth time, they went back – into the fury of that village, under fire that seemed to come from every window, every doorway, every alley. And when they finally got to those trapped Americans, Dakota jumped out. And he ran toward them. Drawing all those enemy guns on himself. Bullets kicking up the dirt all around him. He kept going until he came upon those four Americans, laying where they fell, together as one team.

Keeping of the Faith with the Highest Traditions of the Marine Corps

“Dakota and the others who had joined him knelt down, picked up their comrades and – through all those bullets, all the smoke, all the chaos – carried them out, one by one. Because, as Dakota says, ‘That’s what you do for a brother.’ Dakota says he’ll accept this medal in their name. So today, we remember the husband who loved the outdoors -Lieutenant Michael Johnson. The husband and father they called ‘Gunny J’ – Gunnery Sergeant Edwin Johnson. The determined Marine who fought to get on that team – Staff Sergeant Aaron Kenefick. The medic who gave his life tending to his teammates – Hospitalman Third Class James Layton. And a soldier wounded in that battle who never recovered – Sergeant First Class Kenneth Westbrook.

“Dakota, I know that you’ve grappled with the grief of that day; that you’ve said your efforts were somehow a ‘failure’ because your teammates didn’t come home. But as your Commander-in-Chief, and on behalf of everyone here today and all Americans, I want you to know it’s quite the opposite. You did your duty, above and beyond, and you kept the faith with the highest traditions of the Marine Corps that you love.

“Because of your Honor, 36 men are alive today. Because of your Courage, four fallen American heroes came home, and – in the words of James Layton’s mom – they could lay their sons to rest with dignity. Because of your Commitment – in the thick of the fight, hour after hour – a former Marine who read about your story said that you showed how ‘in the most desperate, final hours – ¦our brothers and God will not forsake us.’ And because of your humble example, our kids – especially back in Columbia, Kentucky, in small towns all across America – they’ll know that no matter who you are or where you come from, you can do great things as a citizen and as a member of the American family.

“Therein lies the greatest lesson of that day in the valley, and the truth that our men and women in uniform live out every day. ‘was part of something bigger,’ Dakota has said, part of a team ‘that worked together, lifting each other up and working toward a common goal. Every member of our team was as important as the other.’

“So in keeping with Dakota’s wishes for this day, I want to conclude by asking now-Gunnery Sergeant Rodriguez-Chavez and all those who served with Dakota – the Marines, Army, Navy – to stand and accept thanks of a grateful nation.

“Every member of our team is as important as the other. That’s a lesson that we all have to remember – as citizens, and as a nation – as we meet the tests of our time, here at home and around the world.

“To our Marines, to all our men and women in uniform, to our fellow Americans, let us always be faithful. And as we prepare for the reading of the citation, let me say, God bless you, Dakota. God bless our Marines and all who serve. And God bless the United States of America. Semper Fi.”

President Obama Placed the Medal of Honor Around the Neck of Dakota Meyer

Following the reading of the citation, President Obama carefully placed the Medal of Honor around the neck of Dakota Meyer as he stood stiffly at attention, eyes straight forward as his proud family, friends and fellow combatants looked on.

As is sometimes the case, however, there was some debate over Meyer’s Medal of Honor and questions raised over former U.S. Army Capt. William D. Swenson‘s recommendation for the Medal of Honor by Marine Gen. John R. Allen, commander of the International Security Assistance Force at the time.

An investigation by McClatchy News Service concluded that the justification for Meyer’s decoration may have been inflated and that the nomination for Swenson’s Medal of Honor may have been intentionally lost.

On December 14, 2011, McClatchy news outlets published an article which questioned the actual number of lives Dakota Meyer saved. The article stated that”crucial parts that the Marine Corps publicized were untrue, unsubstantiated or exaggerated,” but that Meyer “by all accounts deserved his nomination.”

Nearly a year later, in September 2012, a McClatchy journalist interviewed nine Afghan soldiers from the Afghan National Army’s 1st Kandak, 2nd Infantry Brigade 201st Corps who had been present at the battle. The Afghan soldiers disputed portions of the USMC’s account of the battle, stating that the Taliban did not charge Meyer’s vehicle and that only two dead Taliban were found after the battle. The Afghan soldiers stated that it was the belated arrival of attack helicopters which finally chased away the Taliban, not the actions of any of the U.S. Soldiers or Marines on the ground. The Afghans added that the three Marines and naval Corpsman, Johnson, Kenefick, Johnson, and Layton, were killed after remaining behind to cover the withdrawal of the Afghan soldiers from the ambush site.

Meyer and Co-Author Bing West Wrote the Book

In response to McClatchy’s findings, the Marine Corps said it stood by the official citation that was produced by the formal vettingprocess. Asked to explain the individual discrepancies and embellishments, the Marines drew a distinction between the citation and the account of Meyer’s deeds that the Marines constructed to help tell his story to the nation. At least seven witnesses attested to him performing heroic deeds “in the face of almost certain death.”

Meyer and co-author Bing West wrote the book ‘Into the Fire: A Firsthand Account of the Most Extraordinary Battle in the Afghan War, about the Battle of Ganjgal.’ It was published on September 25, 2012. In the book, Dakota Meyer makes a case for Army Capt. William D. Swenson to be awarded the Medal of Honor; Swenson had criticized Army officers at the nearby Forward Operating Base Joyce for not providing fire support, the resulting political fallout not conducive to awarding him the medal. Those same officers were later cited following a military investigation for “negligent” leadership leading “directly to the loss of life” on the battlefield.

In August 2012, California Representative Duncan D. Hunter wrote to Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta regarding the Medal of Honor nomination of Swenson. In January 2013, Hunter said Swenson’s nomination had been awaiting President Obama’s approval at the White House since at least July 2012.

Swenson was awarded the Medal of Honor on October 15, 2013

A year after the battle, suffering from PTSD, and after a night of heavy drinking, Meyer attempted suicide with what he thought was a friend’s loaded weapon, which turned out to be unloaded.

In September 2011, Kentucky Governor Steve Beshear bestowed upon Meyer the honorary title of Kentucky Colonel during an event in his hometown of Greensburg in which Meyer served as grand marshal.

On March 13, 2015, Dakota Meyer became engaged to Bristol Palin, daughter of former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin. After a tumultuous year of on-again, off again relationship and the birth of a daughter together, Meyer and Palin were married on June 8, 2016. In December 2016, Palin announced that she was expecting a girl, the couple’s second child together.

Fantastic story! That says it all.