Steeped in secrecy and shaped by global Cold War tensions, the Vietnam War was, by all standards of measure, the most clandestine military campaign in US history. After World War II, democratic and communist nations were spoiling for a fight, testing one another, and positioning themselves to gain geographic and political advantage. However, with an indecisive outcome in Korea and escalating international anxiety, further activities became highly secretive on both sides, including CIA involvement in Vietnam beginning in 1953. Leading to covert 1961 combat operations in North Vietnam code-named Operation 34A, these highly classified and largely unsuccessful attacks reflected other events of that time, e.g., the Bay of Pigs (April 1961) and the Cuban Missile Crisis (October 1962). These CIA missions, comprised of air and naval infiltration, led to significant loss of life. To increase the chances of success, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam- Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) was created, and Operation 34A was transferred in July of 1964. Tasked initially with covert missions against Northern Vietnam, MACV-SOG entered the world of shadow warriors and covert operations, much of which remains classified to this time.

Foundation of MACV-SOG

Established on January 24, 1964, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) was a highly classified, multi-service special operations unit conducting covert and unconventional warfare, both before and during the Vietnam War. Created by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, MACV-SOG conducted strategic reconnaissance missions in South Vietnam, North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, taking enemy prisoners, rescuing downed pilots and prisoners of war throughout Southeast Asia, and conducting clandestine agent team activities and psychological operations. It eventually consisted primarily of personnel from the United States Army Special Forces, the United States Navy SEALs, the United States Air Force (USAF), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and elements of the United States Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance units– every one a volunteer. The force was above top secret – operatives were sworn to secrecy for over twenty years, which sadly meant that families of MACV-SOG members were not informed if their loved ones were killed in action. To prevent detection, SOG personnel carried no identification, uniforms were sterilized of all insignia, serial numbers were removed from their weapons, or captured enemy ordinance was used. Additionally, to best preserve the US assertion that no troops were operating outside South Vietnam, SOG reported directly to MACV, devoid of the military chain of command.

MACV-SOG Had an Decisive Impact on the Vietnam War

Integral to accepting responsibility for Operation 34A in July 1964, MACV-SOG had an immediate and decisive impact on the war, leading to rapid escalation. Throughout 1963 the South Vietnamese regime of Ngo Dinh Diem was losing the war. Concerns intensified further when Diem was overthrown and killed in a CIA-sponsored coup in November, along with the assassination of President Kennedy. With MACV-SOG in place, on the night of July 30 and 31, 1964, four SOG PTF boats shelled islands off the coast of North Vietnam, the first time SOG employed seaborne shelling. At the same time, a SOG Agent Team was inserted into North Vietnam but was detected by the Viet Cong. The very next afternoon, the destroyer USS Maddox began a coastal intelligence-gathering mission in the Gulf of Tonkin, prompting three Viet Cong torpedo boats to attack the Maddox on August 2nd, though the destroyer was undamaged. On the night of August 3rd and 4th, three SOG vessels again shelled targets on the mainland of North Vietnam. Joined by the destroyer USS Turner Joy on August 4th, the Maddox reported to Washington that both ships were under attack by unknown vessels, assumed to be North Vietnamese. In response, President Johnson launched Operation Pierce Arrow, an aerial attack against North Vietnamese targets. Moreover, and of historical importance, Congress authorized the Southeast Asia Resolution giving President Johnson power to do whatever was necessary to support the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty– without a declaration of war. Unknown to Congress, however, was that SOG operations were conducted in the same area as the Maddox, and there was only a single Viet Cong attack on US vessels.

Central to accelerating US involvement throughout Southeast Asia, SOG participated in the most significant campaigns of the Vietnam War, including Operation Steel Tiger, Operation Tiger Hound, the Tet Offensive, Operation Commando Hunt, and the Cambodian Campaign Operation Lam Son 719, and the Easter Offensive. Officially SOG was authorized for a wartime high of 394 US personnel, but to accomplish their missions, support was necessary from a number of Army, Air Force, Marine, and South Vietnamese units that totaled 10,210 military and civilian personnel working for MACV-SOG, including seven CIA operatives. To manage the growing complexities, SOG developed Operational Groups (Maritime, Airborne, Psychological, and Air) commanded from headquarters in Saigon, increasing in size and scope throughout the war.

Perhaps the least known aspect of SOG’s original missions consisted of psychological operations conducted against North Vietnam and comprised of radio broadcasts (e.g., “Voice of the SSPL”), leaflet drops, and gift kits containing pre-tuned radios which could only receive broadcasts from the unit’s transmitters. SOG also broadcast “Radio Red Flag,” programming purportedly directed by a group of dissident communist military officers. Both stations condemned the PRC, the South and North Vietnamese regimes, and the US in favor of traditional Vietnamese values. Straight news, without propaganda embellishment, was broadcast from South Vietnam via the Voice of Freedom, another SOG creation.

By September 1965, the Pentagon authorized MACV-SOG to begin cross-border operations in Laos along South Vietnam’s western border, though not officially acknowledged until 1971. MACV wanted boots on the ground since 1964 to observe the enemy logistical system operating on and around the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Earlier strategic bombing efforts in April (Operation Steel Tiger), through the 7th Air Force, were wholly unsuccessful. Equally, all-Vietnamese reconnaissance efforts (Operation Leaping Lena) proved disastrous. US troops were necessary, and SOG launched Laotian operations beginning in October 1965. In what became a longstanding practice, SOG conducted prisoner snatch missions behind enemy lines along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. No matter the primary mission, capturing enemy soldiers remained the team’s secondary objective to gather valuable intelligence relating to troop movements, size, and base locations. However, teams also received rewards, including free R&R trips to Taiwan or Thailand, a $100 bonus for each US team member, a Seiko watch, and cash to each indigenous member. SOG most often operated using teams comprised of two-to-three Americans and six-to-nine indigenous personnel (Vietnamese, Montagnards, Cambodians, or ethnic Chinese). When launching a cross-border recon operation, SOG teams would enter a pre-mission “quarantine,” much like modern-day Army Special Forces operational detachments do before deploying. During this quarantine period, they would eat the same food as the North Vietnamese, so they- and their human waste- would smell like the enemy while in the jungle.

During 1966 it became obvious the North Vietnamese were using Cambodia, a supposedly neutral country, as part of their logistical system. However, the extent of operations was unknown. In April 1967, MACV-SOG was ordered to commence Operation Daniel Boone, a cross-border reconnaissance effort into Cambodia, though, like Laos, not acknowledged until 1970. But unlike Laos, SOG and the 5th Special Forces Group were initially constrained in their efforts. Reconnaissance teams had to cross the border on foot, had no tactical air support or Forward Air Controllers, and relied almost solely on stealth. Though SOG’s Air Operations Group had been augmented in September 1966, alongside support by the 15th Air Commando Squadron and the 20th Special Operations Squadron, air support was not authorized in Cambodia until much later, and then in the form of dedicated Huey gunships and transport.

Early on, SOG involvement was growing and becoming more diverse. In September 1966, the Joint Personnel Recovery Center (JPRC) was established by MACV and immediately assigned to SOG. The JPRC was to compile information on POWs, MIA, and escapees, planning missions to free and recover US and allied personnel. Additionally, SOG was responsible to conduct post search and rescue (SAR) operations when all other efforts had failed. SOG carried on this mission until the unit was disbanded in 1972, at which time responsibility to repatriate some 2,500 missing military and civilian personnel passed to a successor organization, the Joint Casualty Resolution Center (JCRC). Operationally, by 1967 MACV-SOG had also assumed the role of supporting construction for the Muscle Shoals electronic barrier system, including reconnaissance and placement of electronic sensors both in the western Demilitarized Zone and southeastern Laos.

Black Year – 1968

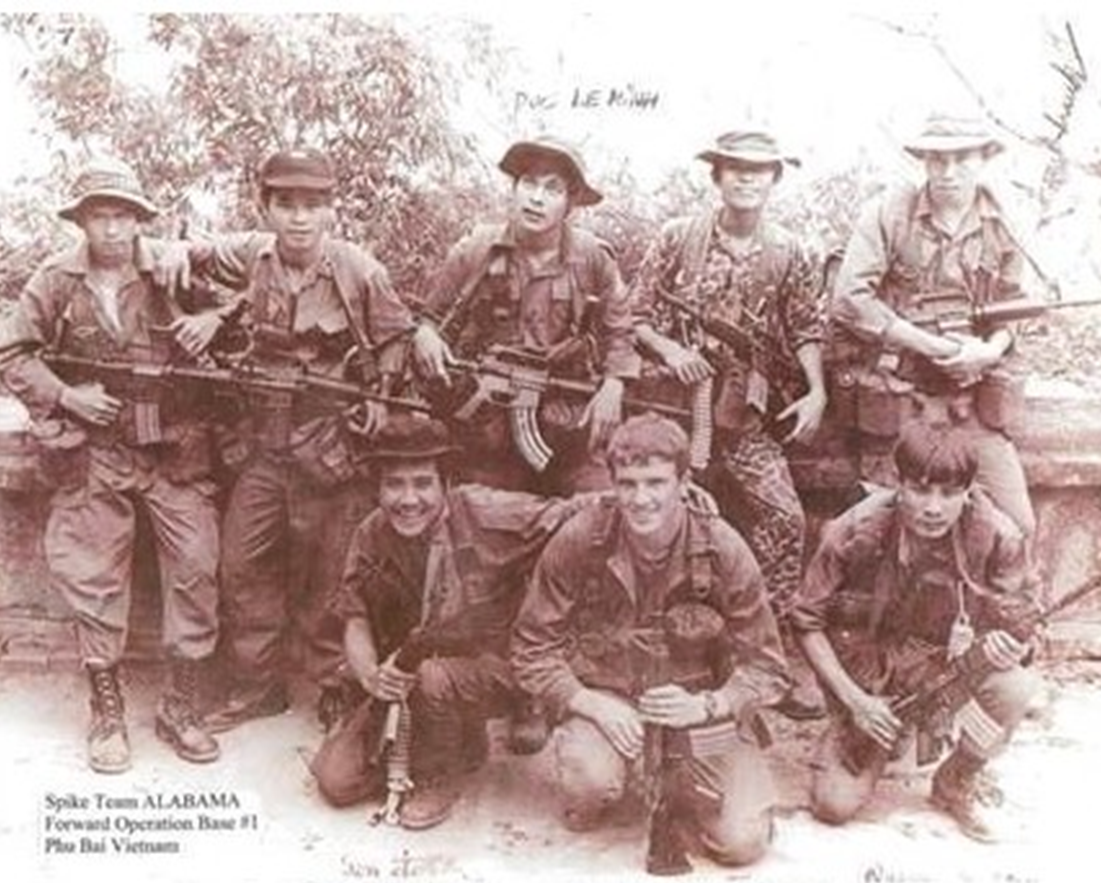

Success in the war through 1967 continues to be controversial, but there is no denying that 1968 was pivotal, signaling a downturn for US forces despite escalating troop commitments. For SOG specifically, the Tet Offensive, the largest Communist assault to that time, inflicted severe losses and caused a collapse of northern operations. Reportedly, the communists offered a medal for any NVA soldier that killed a SOG member. For most of the year, MACV-SOG centered around in-country missions supporting field forces. However, on the morning of October 5th, all that would change with a reconnaissance mission by Recon Team Alabama that proved legendary. The insertion of Alabama’s nine-man team started smoothly enough, but almost immediately, an NVA flag was spotted, signaling regimental strength in the area. Rather than abort, the team continued on, but only to realize the mission had been compromised, and they were walking into an ambush. In the ensuing melee, growing numbers of NVA were killed as Team Alabama was encircled, and the enemy dead were stacked up to create a perimeter wall. Over the next several hours, Phantom jets dropped napalm on advancing enemy troops while helicopter gunships resupplied the soldiers of Team Alabama and provided supporting fire. Under the leadership of Specialist Fourth Class Lynne M. Black Jr. and Cowboy, a South Vietnamese Team Leader, extraction was ultimately achieved. Only after the engagement was it determined that an NVA division numbering 10,000 had been committed to the action, with ninety percent killed or wounded.

Meanwhile, peace negotiations were stalled, and the US was anxious to reopen discussions with Hanoi. Though North Vietnam was looking for the US to cease its air campaign (Operation Rolling Thunder), President Johnson instead enacted a cessation of all US operations north of the 20th parallel, both overt and covert. This order effectively ended MACV-SOG’s agent team, propaganda, and aerial operations. In reality, intelligence returns from the northern agent teams had been disappointing, and more than three-quarters of the agents inserted, some 456 South Vietnamese, had been captured. Years after the war ended, it was discovered there was a mole at the SOG headquarters in Saigon, passing information on team missions and locations to the enemy.

Consequently, by 1970 SOG found their time on the ground both shortened and more dangerous, evidenced by more and more teams being eradicated. In fact, MACV-SOG had a casualty rate exceeding 100%, one of the highest of any US force. This translates to every single SOG officer being wounded at least once and over half of the force killed in action.

The Unit Was Downsized and Renamed

The US military and MACV-SOG kept tight security over the unit’s existence until the early 1980s. The unit was downsized and renamed Strategic Technical Directorate Assistance Team 158 on May 1, 1972, to support the transfer of its work to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam under the Vietnamization program. In recognition of their contributions, bravery, and devotion to duty, MACV-SOG was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation (April 2001), thirteen Congressional Medals of Honor, twenty-two Distinguished Service Crosses, and a host of others. Service with SOG meant a life filled with peril and the likelihood of dying in anonymity. But, for this elite, all-volunteer force, it also came with the reassurance of working alongside the best and confidence borne from an unbreakable bond of loyalty and trust.

Tremendous story. Had a Gunnery Sergeant who I served with that was in MACV-SOG. He was a recipient of two Bronze Stars with Combat “V” distinguishing device. Of special note – There is no such award as the “Congressional Medal of Honor”! The proper title of this award is the “Medal of Honor”. Congress has nothing to do with the award process – thank God.

My father sfc Henry Gainous served in this unit if anyone severed with him I would like to hear from them you can email me at [email protected]

Hi there. My father was on a MACV Team for one deployment. Another he was ARVN. First time out he was a door gunner . My father returned home in 1971, I was born end of December 1972. He never spoke about any of it.

My brother also served. I know because the vague story he told didn’t match anything else I have heard about. I was born in 1964, my brother James C Duncan (Jimmy) 7/7/49 enlisted after HS graduation. I believe he landed in Vietnam in 68.

He was a Green Beret but he was stationed in Thailand. Almost everyone I spoke to said he couldn’t have been stationed in Thailand but he said that indeed he was and would paratroop over the border at night. Those people in the know would mention Cambodia or Laos but he said no, Vietnam. He was always a bit wild and crazy but he must have been insane with a death wish to volunteer. Either that or naive. I can believe that too. We grew up in a small town. Still wild and crazy, but he wasn’t the same when he came home. I saw him a few times over the years but he was seldom sober. He loved dad but hated my mom. And since she had control of me he stayed clear of my life. I do have a few pics, some from special training.

I did finally reconnect over the phone with him and I’m glad I did but he was too far gone. The alcohol finally won in 2019. His HS friend and I were in contact for awhile. He says he went through his things and found a silver star. The paperwork said Jimmy’s team took artillery, his helicopter shot down, and everyone in his team was down except him. He called for extraction and gathered all the bodies but the extraction helicopter was downed too. He retrieved the body of the pilot, along with the rest of the team, and dragged them all to the second extraction point, successfully making it back to base. No idea where the silver star is today

My brother never told me that story, he told a different story of a young girl, a child, I think, throwing a grenade into a helicopter on the base. He says he shot her. He says that he was offered a purple heart for that but he refused. “I shot a little girl and they wanted to give me a medal for that!” I could tell this affected him greatly. I thought maybe he’d seen too much TV or something but after finding out about SOG everything fits.

If anyone has ANY information about my brother please contact me. If he was a hero, and I believe this true, no one knows. And that’s so unfair. I would like to honor him but literally have nothing, not even his ID and nowhere to start. I love him very much. Can you please help me? Thank you. And I rarely say this because it’s so trite, but thank you for your service.

If I could read the Silver Star citation. I might be able to answer, some of your questions Paula. About his service and being stationed in Thailand. (Note: I just came across your comment). Check my bio on FB – Ken Holmes. I’m the guy in uniform.

I WAS WITH THE 1ST CAV. DIV. AIRMOBILE 1967 TO 1968 “TET”

My husband Frederick Lance Hubel was assigned to SOG, FOB2, 1968-1969. He is now 80 yrs old, if anyone served with him, would love to hear from you.

I need information on my uncle sfc Howard b.Lull Jr. He was mia-kia he served in provincial recon unit. Lost in the battle loc ninh April 7th 1972 .Any info greatly appreciated. Thanks

That last photo, in front of the RT Montana sign, is a phony. It’s one of those groups that dress up like SOG guys and camp out. A dead giveaway is that he has a name tag. SOG recon wore sterile uniforms. Not a big deal, but it should be changed.

Tim Schaaf