The American Ace of Aces, Eddie Rickenbacker, was a successful race car driver, fighter pilot, an airline executive, wartime advisor, and elder statesman. Few aces achieved so much in so many different lifetime roles. His twenty-six aerial victories came after only two months of combat flying, a spectacular achievement.

Eddie Rickenbacker Set a Speed Record in a Blitzen Benz

His family name was originally spelled “Reichenbacher,” anglicized to its more familiar form when the U.S. entered World War One. His father died when Eddie was twelve, and the youngster quit school to help support his mother. He found a job with the Frayer Miller Air-cooled Car Company, one of the thousands of automobile companies that emerged in the early 1900’s.

From his job road-testing cars for Frayer-Miller, he made his way into automobile racing, racing for Fred Duesenberg, among others. He raced three times in the Indianapolis 500 and set a speed record of 134 MPH in a Blitzen Benz.

He became one of the most successful race car drivers of the era, earning $40,000 per year (a great sum at that time).

When the United States entered the war, Eddie Rickenbacker proposed a flying squadron staffed by race car drivers. The Army didn’t accept his suggestion, but did accept his personal services; he became a driver for the Army General Staff (but not chauffeur to General John “Black Jack” Pershing as frequently claimed). Once in France, he hoped to transfer into aviation.

Eddie Rickenbacker got a break one day when he had a chance to fix a motorcar carrying Colonel Billy Mitchell, then chief of the Army’s Air Service. He made his interests known to Mitchell, and Rickenbacker, then at the advanced age of twenty-seven, entered pilot training. Because of his mechanical skills, he was first made engineering officer at the Issoudun aerodrome, but he flew whenever he could.

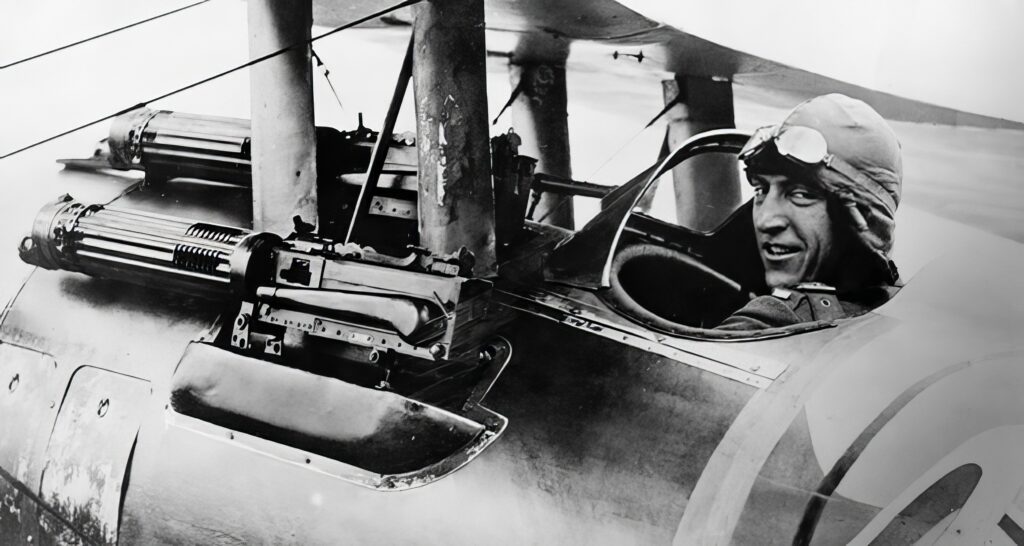

In March 1918, he was assigned to the newly formed 94th Pursuit Squadron, which included: James Norman Hall (of the Lafayette Escadrille), Hamilton Coolidge, James Meissner, Reed Chambers, and Harvey Cook. But no airplanes! Once they secured some cast-off Nieuports, they moved up to the front.

Before April 3, 1918, only the 94th, commanded by Major John Huffer, (one of the old Lafayette flyers), and Captain James Miller’s squadron, the 95th, were at the front. Both squadrons had been at Villeneuve and together had moved to Epiez. None of the pilots of either squadron had been able to do any fighting, owing to the lack of airplane guns. In fact, the pilots of Squadron 95 had not yet been instructed in the use of airplane guns. The 94 Squadron pilots, however, had been diverted to the Aerial Gunnery School at Cazeau for a month early in the year and were ready to try their luck in actual combat fighting over the lines. But they had no guns on their machines before April 3. Then suddenly guns arrived! All sorts of wonderful new equipment began pouring in. Instruments for the airplanes, suits of warm clothing for the pilots, extra spares for the machines. Shortly, they moved up to an aerodrome at Toul. Here, they unpacked, organized the squadron, and selected the famous “Hat-in-the-Ring” insignia.

On the 6th, Maj. Raoul Lufbery selected “Rick” and Douglas Campbell for the squadron’s first flight over German lines. As he eyed the trenches and desolation of war from 15,000 feet up, suddenly “Archy,” German anti-aircraft fire opened up. Carefully shepherded by Lufbery, it was an uneventful flight, but back on the ground, the experienced Lufbery chided the two novices for failing to notice other planes that he had seen. And for a good measure, he casually poked his fingers into several shrapnel holes in Rickenbacker’s Nieuport.

On the 14th, a patrol of Eddie Rickenbacker, Capt. Peterson and Lieutenant Reed Chambers was ordered to fly from Pont-a-Mousson to St. Mihiel at 16,000 feet. Lieutenants Douglas Campbell and Alan Winslow were directed to stand by on the alert at the hangar from six o’clock until ten the same morning. Rickenbacker’s patrol got separated in fog and didn’t accomplish too much, but as they returned, the “alert” pilots, Campbell and Winslow, intercepted two Boche airplanes and sent them both down. The newspapers made a huge fuss over the first “American” victories of the war.

For ten weeks Eddie Rickenbacker flew strafing missions and fruitless sorties before shooting down his first enemy plane. One day he encountered a Spad with French markings that almost shot him down, a lesson well-learned. He made several mistakes in this early period: getting lost, mistaking friends for foes, falling into German aerial ambushes, etc. He later reflected that these early disappointments and lessons gave him enormous benefits in his subsequent flying.

April 29th was a wet day; he and Capt. James Norman Hall had the afternoon alert. At five o’clock Capt. Hall received a telephone call from the French headquarters at Beaumont stating that an enemy two-seater machine had just crossed the lines, flying south.

Hall and Rickenbacker had been on the field with their flying clothes on and their machines ready. They jumped into their seats and the mechanics twirled the propellers. Just then the telephone sergeant told Capt. Hall to wait for the Major, who would be on the field in two minutes. “Rick” scanned the northern heavens and spotted a tiny speck against the clouds above the Forêt de la Reine; it was the enemy plane. The Major was not yet in sight. Their motors were smoothly turning over and everything was ready.

Deciding not to wait for the Major, Capt. Hall ordered the blocks pulled away from the wheels. His motor roared as he opened up his throttle and in a twinkling, both machines ran rapidly over the field. Side by side they arose and climbing swiftly soared after the distant Boche. In five minutes they were above the observation balloon line which stretched along two miles behind the front. Eddie Rickenbacker could still distinguish their unsuspecting quarry off toward Pont-a-Mousson. He briefly left Hall to pursue a French three-seater, but recognized the ally before firing, and rejoined Capt. Hall.

Eddie Rickenbacker Had Brought Down his First Airplane Without Taking a Single Shot!

Hall led them up the sun, gaining an advantageous position over the new Pfalz fighter that he had spotted. Coordinating skillfully, Rickenbacker cut off the German’s retreat while Hall dived at him, from out of the sun. As the German tried to escape eastward, Rickenbacker opened his throttle and was on him. At 150 yards he pressed the triggers. The tracer bullets cut a streak of living fire into the Pfalz’s tail. Raising the nose of his airplane slightly the fiery streak gradually settled into the pilot’s seat. The Pfalz swerved, out of control. At 2000 feet, Eddie Rickenbacker pulled up and watched the enemy machine continuing on its course. Curving slightly to the left the Pfalz circled and crashed at the edge of the woods a mile inside the German lines.

Lt. Eddie Rickenbacker had brought down his first enemy airplane without taking a single shot! He and Hall did aerobatics all the way back to their field, where they received the hearty congratulations of their mates, on the squadron’s third victory.

Rickenbacker Scored his Second Victory While Flying With Reed Chambers

While April’s rainy weather inhibited flying, the 94th saw more action in May 1918. On the 2nd, James Meissner outmaneuvered an Albatross, sent it into a spin, and dived after it. Firing until the German plane spouted flames, Meissner didn’t immediately notice the fabric peeling off his left upper wing. With careful flying, he made it back the 94th, with the squadron’s fourth victory confirmed by a French observation post. That same day, the 94th suffered its first casualty when Charley Chapman’s Nieuport was flamed by a two-seater. On the 7th, while dogfighting four Germans with Rickenbacker and Green, the wing of Hall’s Nieuport stripped; he crash-landed and was captured. Rickenbacker replaced Hall as commander of the squadron’s Number 1 Flight.

Rickenbacker scored his second victory while flying with Reed Chambers. On the morning of the 17th, he and Chambers took off before dawn in an effort to catch some German planes unawares. After fruitless circling at 18,000 feet, Rickenbacker headed for the German stronghold of Metz, losing Chambers in the process. Finding no Hun air activity over Metz, he then flew over an airdrome at Thiaucourt, where he noticed three Albatrosses taking off. He eased down lower, unnoticed by the enemy airplanes until “Archy” gave him away. Diving at 200 MPH, he fired a long ten-second burst, until, at 50 yards, the Albatros pilot was hit. When Rickenbacker pulled out of his dive, the Nieuport cracked and the upper wing covering came off. He spun down, apparently a certain casualty, but managed to re-start his engine and pull out at about 2,000 feet. He landed safely and even had his victory confirmed.

On May 30, 1918, Rickenbacker claimed two German airplanes, to become an ace. Once again, Jimmy Meissner lost the upper wing of his Nieuport. By then, the American pilots were anxious to discard the Nieuports, for the heavier, stronger Spads, as the French had already done.

Rickenbacker continued to prowl the skies, looking for victories and learning more. On the 4th of June, he cornered a Rumpler, two-seater observation plane with the number ’16’ painted on its fuselage. His gun promptly jammed, and number ’16’ escaped. The next day, flying Lt. Smyth’s plane while the guns in his plane were being repaired, he chanced upon Rumpler number ’16’ again! This time the Rumpler pilot evaded by zooming upward and giving Rickenbacker a taste of its floor-mounted machine gun. Its skillful pilot kept him at bay for over half an hour, working his way back over German lines. “Rick” regretfully turned home, and his engine froze up; he had exhausted its oil supply in his two-and-a-half hours of combat flying. Once again, he squeaked through to a safe landing. For the next two days, he stalked the predictable number ’16’ which easily evaded him by seeking higher altitudes, even when he used the Nieuport in the squadron reputed to have the highest ceiling. Some wags suggested that he could gain some extra altitude by leaving his guns behind, or perhaps even more by omitting that heavy fuel!

After this useless exercise, he took a leave in Paris. He didn’t fly much in June, due to a persistent ear infection. But late in the month, he did participate in an early American effort to emulate the largely organized formations of fighters that the Germans used so effectively. The three U.S. squadrons got hopelessly mixed up.

Loomis organized an early morning attack on German observation balloons, Drachen, which was depressingly unsuccessful. On June 27, all four of the U.S. Pursuit Squadrons in France (the 94th, 95th, 27th, and 147th) moved from the Toul to Chateau-Thierry sector, to “an old French aerodrome at Touquin, a small and miserable village some twenty-five miles south of Château-Thierry and the Marne River.”

July was not much better; little flying a no victories. He was briefly hospitalized with pneumonia and then visited Paris on the 4th of July. He dropped in at the U.S. supply depot at Orly, found some new Spads there, and flew a “borrowed” one back to the 94th.

By August 8, the 94th received newer, faster Spads to replace their Nieuports, promising even greater results. But Rickenbacker’s ear infection grounded him for much of August, as well.

Rickenbacker and Chambers Both Believed They Had Downed Fokker

On that day, He went up with 11 Spads of the 94th, escorting a pair of French two-seater photo planes over Vailly. When two small groups of Fokkers attacked, the 94th pilots successfully protected the photo planes. Rickenbacker and Chambers both believed they had downed Fokker, but their claims were unconfirmed, as the combat took place well over German lines. On a similar mission on the 10th, when escorting some Salmson photo machines over the Vesle and Aisne rivers, they met some Fokker D.VII’s, but all Rickenbacker got was three bullet holes in the fuselage of his Spad. He spent late August in the hospital, returning on Sept. 3rd, when the 94th Squadron moved back to the Verdun sector, to a little town named Erize-la-Petite.

During the month of September, he scored four more victories and rose to command the 94th Squadron.

He assumed command on Sept 24; the first thing he did was check the operations records and he found that the 27th Squadron was leading the 94th in victories, largely due to Frank Luke’s balloon-busting spree. By the end of the month, the 94th had recaptured the lead.

While flying over Etain on the 25th, Rickenbacker picked up a pair of L.V.G. two-seater machines, escorted by four Fokkers. He climbed into the sun unnoticed, got well in their rear, and made a beeline for the nearest Fokker. With one long burst, he sent it down. The other Fokkers scattered, and he took the opportunity to make a pass at the LVG’s. After several maneuvers, he flamed one of those, too.

Sept. 26, 1918, was a big day. Forty thousand American doughboys were going over the top, in an offensive from the Meuse River to the Argonne forest. In support of this, the 94th Pursuit Squadron was charged with destroying German observation balloons. He and five of the 94th’s best pilots, Lieutenants Cook, Chambers, Taylor, Coolidge, and Palmer; gathered for an early breakfast, and went over their plans. Two balloons assigned to the 94th, and three pilots were delegated to each balloon. Both lay along the Meuse between Brabant and Dun. They eluded the Archy fire to bring down both balloons, and “Rick” downed a Fokker

As commander of the 94th, nicknamed the “Hat in the Ring” Squadron, he displayed the managerial skills that served him so well in later endeavors. He drove his men hard and demanded results. They rose early for calisthenics; inspections were frequent and detailed; waste was not permitted. Rickenbacker insisted:

“Every plane must be ready to take-off any moment, day or night, guns loaded, gassed, engine tuned. If all was not correct, the war could be lost”.

He also spent as much time as possible leading patrols in the air, delegating operational issues to different officers. Billy Mitchell was delighted at his protege’s success. His reports glowed with both Rickenbacker’s aerial and organizational successes.

He and Reed Chambers shared a victory over a Hanover recon plane on October 2nd, this on a day when they were flying low-level ground-support patrols. Within a few minutes of this action, a flight of Fokkers appeared, chasing Rickenbacker down toward the ground. Reed Chambers and other Spads arrived in the nick of time, and the whole circus was soon climbing to gain the shelter of some low-hanging clouds. Recovering from his dive, Rickenbacker and Chambers sought a place between the Fokkers and their lines where they might be expected to issue out and make for home. They caught them and promptly sent two of them crashing inside the American lines. All three of their victories were promptly confirmed.

Twelve years after the war ended, he was belatedly awarded the Medal of Honor for his accomplishments.

In the early 1920’s, he secured backing for a new automobile company under his name. It was a well-designed, even advanced, car featuring four wheel brakes, but offered at the wrong time. Soon, his new company was bankrupt.

Starting in the early 1930’s, he owned or managed various commercial airlines, notably Eastern Airlines, which had its roots as a division of General Motors. He became General Manager of Eastern in 1933, and in 1938, with a group of investors, he bought it and became its President. Starting with an aggressively low bid ($0!) for a government airmail contract, he managed the company profitably for twenty years.

During WWII, he carried out special assignments for Henry Stimson, the Secretary of War. In October 1942, flying in a B-17 over the Pacific, on such a mission for Douglas MacArthur, the plane went down in the Pacific. In a horrifying ordeal, Rickenbacker and seven other men, rode a raft for twenty-two days before they were rescued. One man died; Rickenbacker, the oldest man in the raft, lost 54 pounds.

He became a spokesman and advocate for conservative causes, convinced that government “socialist” programs were ruining the country. He died on July 23, 1973 (aged 82) in Zurich, Switzerland.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about Eddie Rickenbacker, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

If my memory is correct, Eddie Rickenbacker also utilized his aeronautical and mechanical skills to help improve the engine performance on the P-38 Lightning during the latter days of WWII.

To prove that he was correct, he flew alongside other combat pilots while on a routine patrol. After the patrol, he enough fuel left over that would have enabled him to extend his range by an additional 200 – 300 miles.