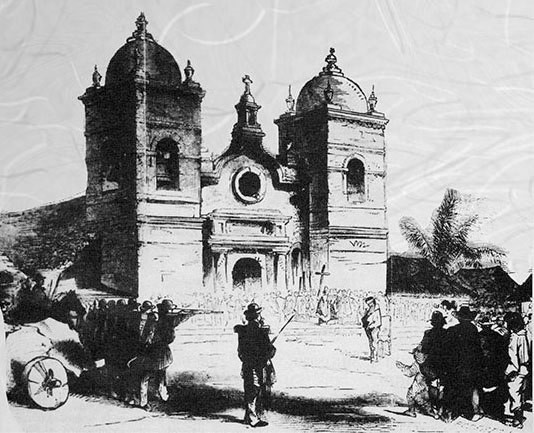

On November 8, 1855, in front of the Parroquia Church in the town square of the Nicaraguan city of Granada, a line of riflemen shot Gen. Ponciano Corral, the senior general of the Conservative government. Strangely, the members of the firing squad hailed from the United States. So did the man who had ordered the execution.

His name was William Walker. Though later generations would largely forget him, in the 1850s, he obsessed the American public. To many, he was a swashbuckling champion of Manifest Destiny. To others, he loomed as an international criminal. In Walker’s own mind, he was a conqueror destined to create a Central American empire. His bizarre career would leave a legacy that shadows the relationship between the United States and Central America to this day.

Biography of William Walker

Walker was born in 1824 in Nashville, Tennessee, to James Walker and his wife, Mary Norvell. His father was the son of a Scottish immigrant. His mother was the daughter of Lipscomb Norvell, an American Revolutionary War officer from Virginia. Lipscomb was also the father of U.S. Senator John Norvell, one of the first senators of Michigan and founder of The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Soon after his birth, Walker began to manifest unusual intelligence. A gifted student, he graduated summa cum laude from the University of Nashville at the early age of fourteen. He then traveled throughout Europe, studying medicine at the universities of Edinburgh and Heidelberg. At the age of 19, he received a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and practiced briefly in Philadelphia before moving to New Orleans to study law.

After a short stint as a lawyer, he became co-owner and editor of the New Orleans Crescent. In 1849 he moved to San Francisco, where the Gold Rush was in its early stages, attracting tens of thousands to California. The Forty-niners were an independent lot, willing to hazard the long, dangerous journey from the settled states. Duels, gunfights, and brawls erupted regularly. Walker himself fought three duels, in two of which he was wounded.

It was also here that his life turned in a radical new direction – a brilliant man obsessed with impractical, grandiose scheming.

Over the previous decade, the United States had expanded deep into Latin American territory, and not always through federal action. Americans in Texas had rebelled against Mexico, established their independence, and won annexation to the United States in 1845. The Mexican War broke out in 1846, leading to the absorption of a third of Mexico – with the assistance of American citizens in California, who staged their own revolt against Mexico.

Enthusiasm for geographical growth came to be known by the newspaper slogan of “manifest destiny,” but it reflected mixed motives. Some Southerners hoped to extend the territory open to slavery. Others felt an evangelical fervor for exporting democracy and Protestantism to the military regimes of Catholic Latin America.

Walker Decided to Become the Greatest Filibuster

This aggressive expansionism gave rise to a strange phenomenon known as filibustering. Filibusters were independent adventurers who launched freelance invasions of foreign countries, usually aiming to annex them to the United States. The decade before the Civil War saw a great flowering of filibustering. In 1850 and 1851, for example, scores of Americans landed in Cuba in disastrous forays.

The restless Walker decided to become the greatest filibuster of them all. In 1853, he invaded Mexico with a handful of men, and barely escaped alive. The United States government tried him for violating the neutrality act, which prohibited private citizens from warring against foreign nations. But a jury in turbulent San Francisco swiftly exonerated him in eight minutes, turning his failure into a personal (if not military) triumph.

William Walker Found his Next Target: Nicaragua

Meanwhile, in 1851, Cornelius Vanderbilt (a wealthy American business magnate and philanthropist known informally as “Commodore Vanderbilt” who had built his wealth in railroads and shipping) had established the Accessory Transit Company to span Nicaragua’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts and connect to his steamships. Accessory Transit carried tens of thousands of passengers each year, making Nicaragua a strategic priority for the federal government. As President James Buchanan later said, “To the United States these routes are of incalculable importance as a means of communication between their Atlantic and Pacific possessions.”

And so, in 1855, Walker found his next target: Nicaragua. But this time, his expedition would be conducted in cooperation with local forces. In its less than two decades of full independence, Nicaragua had suffered from repeated civil wars, waged by the leaders of its two main cities, Leon and Granada – capitals respectively of the Liberal and Conservative Parties. When the Liberals rose in yet another revolt, Byron Cole, a friend of Walker’s, negotiated a contract for Walker to fight on their side.

On May 4, 1855, Walker slipped out of San Francisco Bay in the brig Vesta, along with fifty-seven followers (one of whom died at sea). Though he spoke little Spanish, he demanded an independent command when he arrived in Nicaragua. He promptly launched a blundering attack and was lucky to survive.

But luck was his foremost attribute. The Liberals’ chief executive and commanding general both died soon after his arrival, making him the senior leader on his side. Then Walker carried out perhaps the only inspired maneuver of his career. He commandeered an Accessory Transit steamboat, landed his men in the rear of Granada, and captured the city. He then took hostage the families of the Conservative leaders, including Gen. Ponciano Corral, a senior general of the Conservative government.

Walker, seeking to consolidate his power in the small country, created a unity provisional government, with the weak Patricio Rivas as president, himself as commander of the army, and Corral as secretary of war. Shortly afterward, Walker put Corral on trial for treason and had him publicly executed on November 8, 1855. The freckle-faced filibuster had made himself into Nicaragua’s strongman.

He would be hard-pressed to remain in power. The neighboring republics, alarmed by his success, prepared for war. And he could not rely on Nicaraguans to fight for him. As he later wrote, “Internal order, as well as freedom from foreign invasion, depended entirely on the rapid arrival of some hundreds of Americans.” And that made him entirely dependent upon the Accessory Transit Company’s steamships to transport these recruits.

William Walker Became Involved in a Plot

Walker’s luck continued to hold. Internal strife marked the Accessory Transit Company‘s operations both at home and abroad, as a power struggle ensued between Cornelius Vanderbilt and the men he had put in place to run the daily operations. Walker became involved in a plot to flip the transit grant from Vanderbilt to a group of these embattled men inside the company headed by one of Walker’s best friends, Edmund Randolph (grandson of a Founding Father and a leading attorney in San Francisco). Walker would revoke Accessory Transit’s Nicaraguan charter, and then seize the company’s riverboats and domestic infrastructure, and give them to his new partners. The new line would carry filibuster recruits from the United States for free, accumulating credits toward the cost of the Transit property in Nicaragua. Vanderbilt attempted to prevent these activities by retaking the company’s steamboats on the San Juan River but failed when the British (who opposed filibustering and claimed a protectorate over Nicaragua’s Atlantic coast) Royal Navy declined to intervene.

In April 1856, Costa Rica launched an invasion of Nicaragua, occupying the city of Rivas. William Walker launched a typical frontal assault and was soundly defeated. But his luck held: a cholera outbreak forced the Costa Ricans to retreat, even as Walker gained hundreds of recruits.

But Walker’s arrogance alienated even his own puppet president, Patricio Rivas, who suddenly denounced him as a usurper and fled over the border. A northern alliance, consisting of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, marched into Nicaragua, occupying Leon on July 12. Walker responded by staging a rigged election that made him president. He declared English to be the official language and issued an edict legalizing slavery. Then the Costa Ricans invaded again from the south.

Walker knew he could survive only if he kept open the flow of reinforcements from the United States. So he decided to withdraw to forts along the San Juan River. He evacuated Granada, leaving a detachment with orders to burn the city to the ground. When the filibusters finished, they erected a sign that read, “Aqui fue Granada” – “Here was Granada.”

Nearing the end of 1856, Walker felt reassured. “Walker, keeping his forces concentrated, can maintain himself in Rivas,” an American naval officer reported. “If the external aids he has hitherto relied upon do not fail him, he will repel his enemies.”

But Vanderbilt was not done, and Walker’s luck was about to run out. By October of 1856, Vanderbilt negotiated an alliance with Costa Rica and dispatched a special agent named Sylvanus Spencer (a New Yorker who had worked on the San Juan River and had precious knowledge of the steamboat operations) to the Costa Rican capital of San Jose. Spencer arrived in San Jose with Vanderbilt’s plan of attack and $40,000 in gold to pay Costa Rica’s expenses. Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora put Spencer in charge of a commando force, which Spencer led through the rain forest to the San Juan River. There, they captured a filibuster strongpoint and a few steamboats. Then Spencer used his knowledge to bloodlessly seize the rest of the boats and forts – sailing up in a captured steamer, giving the right signals, then surprising the filibusters with soldiers who had been hiding on deck. Within days, Spencer controlled the river. Walker’s confederates, unable to send passengers and reinforcements across Nicaragua, immediately withdrew their ships. William Walker was isolated.

Walker withdrew into Rivas, where the Central American alliance besieged him for months. Finally, on May 1, 1857, he surrendered to an American naval officer, who conducted him and his men out of the country.

Wherever William Walker Went in Was Greeted by Throngs of Admirers

And so he tried again, and again. On November 25, 1857, he landed at Greytown with 270 followers; in a controversial move, the U.S. Navy forced his prompt surrender. Walker launched a final invasion in 1860. But now his luck finally ran out for good. The Royal Navy captured him, then handed him over to the nearest Hondurans authorities, who executed him on September 12, 1860. He is buried in the Cementerio Viejo in the coastal town of Trujillo. William Walker was 36 years old.

But the federal government proved ineffectual in either convicting William Walker in court, or in preventing further expeditions. Wherever Walker went in the United States, he was greeted by throngs of admirers.

The Fight to Eject Walker Forms Part of Nicaragua’s National Legend

Within a year, the United States plunged into the Civil War. Places with names like Antietam, Shiloh, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness soon obscured Granada, Rivas, and Greytown in the American imagination. Memories of the filibuster faded. But Walker himself had contributed to – or reflected – the nation’s descent into war over the issue of slavery. He had emerged out of a rising tide of freelance violence, and he had appealed to Southern hopes for expanding slavery by reinstituting it in Nicaragua.

Though he has been largely forgotten in the United States, he is still remembered by Central Americans, who see him as a symbol of imperialism. The fight to eject Walker forms part of Nicaragua’s national legend, a critical period in the formation of its national identity.

If nothing else, his military dictatorship, and his ruthless violence – particularly his wanton destruction of Grenada, one of the oldest cities in the western hemisphere – prove that he was one of the most dangerous international criminals of the nineteenth century, if not all our history.

Editor’s Note: My wife’s great grandfather on her mother’s side was Harris Woolf Mallitz, who was Treasure of the Nicaraguan government for years. Born in Kovno, Lithuania, he and his parents came to San Francisco when he was 14 years old. In his late 20s, he departed for Peru, where he met and married Sarah Green and began a successful political life in Latin America. According to records, he fled the United States as a fugitive from justice following a September 28, 1877 document signed by President Rutherford B. Hayes authorizing two San Francisco detectives to take him into custody. Little is known as to the nature of his crime or why the warrant reached the office of the President of the United States.

He and his wife and children left Nicaragua in 1906 and settled in New Orleans. He died at the age of 80 in June 1933.

Read About Other Military Myths and Legends

If you enjoyed learning about the legendary heroes of the United States Air Force, we invite you to read about other military myths and legends on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

My Great Grandmother’s brother was in Nicaragua with Col. Walker. He wrote a book about his experiences in this and the War Between The States. He mentioned that as they left Nicaragua, one of the ship’s boilers exploded and killed many of Walker’s men.