Stories of Gregory “Pappy” Boyington are legion, many founded in fact, including how he led the legendary Black Sheep squadron, and how he served in China as a member of the American Volunteer Group, the famed Flying Tigers. He spent a year and a half as a Japanese POW, was awarded the Medal of Honor and Navy Cross, and was recognized as a Marine Corps top ace. Always hard-drinking and hard-living, Pappy’s post-war life was as turbulent as his wartime experiences.

Biography of Gregory “Pappy” Boyington

Born on Dec.4, 1912, in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, young Boyington had a rough childhood, as divorced parents, an alcoholic step-father, and lots of moves withheld much-needed parental guidance. He got his first ride in an airplane at the ripe young age of six, when the famous barnstormer, Clyde Pangborn (who later flew the Pacific non-stop), flew his Jenny into town, and young Gregory wangled a ride. What a thrill for a little kid!

In 1926, at the age of 13, his family moved to Tacoma, Washington. In high school, he took up a challenging sport that he would practice for many years – wrestling. As an adult, the hard-drinking Boyington would often challenge others to impromptu wrestling bouts, frequently with injurious results.

After graduating high school in 1930, Boyington attended the University of Washington in Seattle, where he was a member of the Army ROTC and joined the Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity. He was on the Husky wrestling and swimming teams, and for a time he held the Pacific Northwest Intercollegiate middleweight wrestling title. He spent his summers working in Washington in a mining camp and at a logging camp, and back in Idaho with the Coeur d’Alene Fire Protective Association in road construction. He graduated in 1934 with a B.S. in Aeronautical

Engineering and soon after married his first wife, Helene, who bore him his first son, Gregory Clark Boyington, 10 months later. He initially worked for a time as a draftsman and engineer for Boeing in Seattle.

Boyington had begun his military training in college as a member of Army ROTC and became a cadet captain. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Coast Artillery Reserve in June 1934, and then served two months of active duty with the 630th Coast Artillery at Fort Worden, Washington.

In the spring of 1935, he applied for flight training under the Aviation Cadet Act, but he discovered that it excluded married men. Boyington had grown up as Gregory Hallenbeck, and had assumed his stepfather, Ellsworth J. Hallenbeck, was his father. However, when he obtained a copy of his birth certificate, he learned that his father was actually Charles Boyington, a dentist, and that his parents had divorced when he was an infant. As there was no record that someone named Gregory Boyington had ever been married, he enrolled in the U.S. Marine Corps Aviation Cadet program using that name.

He began elimination training in June 1935, where he met Richard Mangrum and Bob Galer, both future heroes at Guadalcanal. He passed and received orders to begin Flight Training at Pensacola NAS in January 1936 with class 88-C. Here he flew a floatplane version of the Consolidated NY-2. Like another great ace, Gabby Gabreski, Boyington had a tough time with flight training and had to undergo many rechecks. On February 18, 1936, Boyington accepted an appointment as an Aviation Cadet in the Marine Corps Reserve.

Until he arrived in Pensacola, Boyington had never touched alcohol. But here, with hard-partying fliers, and the burden of his wife’s “indiscretions,” he soon discovered an affinity for liquor. Early on, he established his Marine Corps reputation: hard-drinking, brawling, well-liked, and always ready to wrestle at the drop of a hat. But he kept flying, all through1936, slowly progressing toward earning his wings, flying more powerful planes like the Vought O2U and SU-1 scouting biplanes. At Pensacola, he also met his future nemesis, Joe Smoak, memorialized in the TV show “Baa Baa Black Sheep” (loosely based on Boyington’s memoirs of the same title) as “Colonel Lard.”

Boyington finally earned his coveted wings on March 11, 1937, when he was designated a Naval Aviator and transferred to Quantico, Virginia, for duty with Aircraft One, Fleet Marine Force. He was discharged from the Marine Corps Reserve on July 1, 1937, in order to accept a Second Lieutenant’s commission in the regular Marine Corps the following day.

Before reporting for his assignment with VMF-1 at Quantico, Virginia, he took advantage of his 30-day leave to return home and reconcile with his wife Helene, who became pregnant with their second child. In those days, Marine aviators were required to be bachelors; Boyington’s family was a secret that he kept from the brass, but he brought them with him to Virginia, installing them quietly in nearby Fredericksburg. He flew F4B-4 biplanes during 1937, taking part in routine training, an air show dubbed the “All American Air Maneuvers,” and a fleet exercise in Puerto Rico.

In March of 1938, VMF-1 aviators took possession of the latest, hottest Grumman fighters, the F3F-2s, the last biplane fighters used by the U.S. Army Air Force. Powered by the mammoth 950 horsepower Wright-Cyclone engine, the fat-bellied aircraft was fast and rugged.

In July, he moved to Philadelphia to attend the ten-month Marine Corps Basic School. Apparently not motivated by the “ground-pounder” curriculum, Boyington here evidenced the weaknesses that would haunt him: excessive drinking, unpaid debts, fighting, and poor official performance. On completion of the course, he was assigned to the 2nd Marine Aircraft Group at the San Diego Naval Air Station, where he took part in fleet exercises off the aircraft carriers USS Lexington and USS Yorktown.

Boyington’s irresponsibility, his debts, and his difficulties with the Corps continued to haunt him. One memorable, drunken night, he meant to show off the swimming prowess he had attained as a swimmer at UW, and attempted to swim across San Diego Bay, but wound up naked and exhausted in the Navy’s Shore Patrol office.

Gregory “Pappy” Boyington First Became Noticed as a Top-Notch Pilot

Despite his problems on the ground, it was during these days of 1940, flying with VMF-2, that Boyington first became noticed as a top-notch pilot. Whatever his other issues, he could out-dogfight almost anyone. Boyington was promoted to First Lieutenant on November 4, 1940, and in December he returned to Pensacola as an Instructor. Once back at Pensacola, his problems mounted when he decked a superior Officer in a fight over a girl (not his wife), and his creditors sought official help from the Marine Corps. His career was a hopeless mess by late 1941.

Rescue came from the Chinese front against Japan. Anxious to help the Chinese in their war against Japan, the United States government arranged to supply fighter planes and pilots to China, under the cover of the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company (CAMCO). CAMCO recruiters would visit U.S. military aviation bases looking for volunteers to help defend China and the Burma Road, critical to maintaining the flow of supplies to anti-Japanese forces in the Far East. The pilots were volunteers only in the sense that they willingly quit their peacetime job with the military; otherwise, they would be handsomely paid through CAMCO. Pilots earned $600 a month, flight leaders $675, plus a fat bonus for each Japanese plane destroyed. This was double or even triple the current military salary for pilots.

In March, CAMCO recruiters began their quest to form the American Volunteer Group (AVG), later known as the famed Flying Tigers in Burma. One recruiter set up an interview room in Pensacola’s San Carlos Hotel, a popular watering hole for pilots. On the night of August 4, Gregory “Pappy” Boyington found himself in the hotel bar simply “looking for an answer.” Payday had been just a few days earlier, but he was already broke. His wife and children were gone, he was deeply in debt, and his superiors were breathing down his neck.

The money looked very good to Boyington. Assured by the recruiter that the program had government approval and that his spot in the Corps was safe, he signed on the spot and promptly resigned from the Marine Corps. While the AVG deal for pilots normally meant a later return to active U.S. military service, in Boyington’s case, his superiors took a different view. They were happy to be rid of him and noted in his file that he should not be reappointed.

Gregory “Pappy” Boyington shipped out of San Francisco on September 24, 1941, on the Boschfontein, of the Dutch Java Line. After docking at Rangoon, the AVG fliers arrived at their base at Toungoo on November 13. During his time with the Tigers, Boyington became a Flight Leader. He flew several missions during the defense of Burma and was frequently in trouble with the Commander of the outfit, Claire Chennault. After Burma fell, he returned to Kunming and flew from there until the Flying Tigers were incorporated into the USAAF.

Boyington claimed to have shot down six Japanese fighters, which would have made him one of the first American Aces of the war. He maintained until his death in 1988 that he did, in fact, have six kills, and the Marine Corps officially credits him with those kills. However, loosely-kept AVG records only credited Boyington with two aerial kills. The difference seems to have been a mere technicality: it was noted that in a raid on Chiang Mai, Boyington was one of four pilots who was credited with destroying 15 planes on the ground. As the AVG paid for destroyed Japanese planes, on the ground or in the air, Boyington lobbied for his share of the Chiang Mai planes or, to be precise 3.75 planes. And so, later at Guadalcanal, he characterized his Flying Tiger record as including “six kills.” For Greg Boyington, the 3.75 ground kill claims added to 2 aerial kills, rounded off to six kills, and established himself as one of the first American Aces. It may have been a “little white lie,” but once his AVG number of six kills found its way into print, and his USMC victories started piling up, there was no going back.

While with the Flying Tigers, Boyington also made the acquaintance of Olga Greenlaw, the beautiful wife of the Tiger’s XO, Harvey Greenlaw. In her own words, Olga “knew how to get along with a man if I like him.” Apparently, she and Boyington “got along.” Olga served as statistician and writer of the Flying Tigers’ Daily Diary for the year they were in China. In 1943, she wrote her own book titled “The Lady and the Tigers” about her experiences with the Squadron.

Gregory “Pappy” Boyington returned to the States in the spring of 1942 and took up with Lucy Malcolmson since his first marriage had fallen apart. With some finagling, undoubtedly helped by the wartime demand for, and a shortage of, experienced fighter pilots, and against the prior recommendations by his superiors, he was reappointed to the U.S. Marines in November, with the rank of Major. In January 1943, he embarked on the Lurline, bound for New Caledonia, where he would spend a few months on the staff of Marine Air Group (MAG)-11. Here, he got his first close look at a Vought F4U Corsair, the fighter in which he would record the majority of his aerial victories.

Gregory “Pappy” Boyington finally secured an assignment to VMF-122 as Executive Officer for a combat tour. As usual, he clashed with his superior. This time it was Major Elmer Brackett. Brackett was shortly removed, and Boyington took over but did not see much action. It was now early 1943, when, as the new CO of VMF-122, his claim of six kills with the AVG first made it into print.

In late May of 1943, Boyington’s nemesis, Lt. Col. Joe Smoak relieved him of his command of VMF-122. Shortly afterward, Boyington broke his leg and spent time in the hospital. In the summer of 1943, as he convalesced, the U.S. Naval Air Forces needed more Corsairs in the fight. Oddly, the key pieces – trained pilots and operational aircraft – were present in the South Pacific, but many of them were dispersed. Boyington was given the assignment to pull together an ad hoc Squadron from available men and planes. Originally, they formed the rear echelon of VMF-124.

In a complex, and common, wartime shuffling of designations, Boyington’s team was redesignated VMF-214, while the exhausted pilots of the original VMF-214 were sent home.

Under Boyington as CO with Maj. Stan Bailey as Exec, they trained hard at Turtle Bay on Espritu Santo, especially the pilots who were new to the Corsair. Two other noted Officers rounded out the Squadron: Frank Walton, a former Los Angeles cop, became the Air Combat Intelligence Officer (ACIO), and Jim Reames the Squadron doctor. Walton would later author “Once They Were Eagles.” While leading this group of young pilots, most in their early 20’s, Boyington – at the advanced age of 30 – picked up the nickname “Gramps.” The press gave him the nickname “Pappy” after he was shot down, which stuck with him for the rest of his life.

Boyington’s Bastards

The new VMF-214 was originally called “Boyington’s Bastards” by his men, since none of them were at the time attached to any units, but was later given the more newspaper-friendly label “Black Sheep” by the top brass. In early September 1943, they were moved up to their new forward base in the Russell Islands, staging through Guadalcanal’s famed Henderson Field.

The Black Sheep fought their way to fame in just 84 days, compiling a record 197 planes destroyed or damaged, troop transports and supply ships sunk, and ground installations destroyed in addition to numerous other victories. They flew their first combat mission on September 14, 1943, escorting Dauntless Dive Bombers to Ballale, a small island west of Bougainville where the Japanese had a heavily fortified airstrip. They encountered heavy opposition from the enemy Zeros. Two days later, in a similar raid, “Pappy” claimed five kills, his best single day total.

In October VMF-214 moved up from their original base in the Russells to a more advanced location at Munda. From here they were closer to the next big objective – the Jap bases on Bougainville. On one mission over Bougainville, according to Boyington’s autobiography, the Japanese radioed him in English, asking him to report his position and so forth. Pappy played along, but stayed 5000 feet higher than he had told them, and when the Zeros came along, the Black Sheep blew twelve of them away and drove off the rest. He even made an unsuccessful play for “Washing Machine Charlie,” a random Japanese Betty bomber with deliberately-unsynchronized engines that would make erratic and inaccurate nocturnal bomb drops over Henderson Field on Guadalcanal.

During the period from September 1943 to early January 1944, Boyington destroyed 22 Japanese aircraft. By late December, it was clear that he was closing in on Eddie Rickenbacker’s record of 26 victories (including his claimed 6 with the AVG). But the strain had begun to tell. On Nov. 19, 1943, his old nemesis Lt. Col. Joe Smoak placed him under arrest for 10 days for speaking to the staff of the Wing Commander without Smoak’s explicit authorization. Then, on Jan. 3, 1944, in a large dogfight in which the Black Sheep were outnumbered 70 to 30, Boyington was shot down. He later claimed three enemy aircraft killed in the aerial battle, one of which was verified.

He landed in the water, badly injured. After being strafed by the Jap fighters, he struggled onto his raft only to be captured by a Jap sub several hours later. They took him first to Rabaul, where he was brutally interrogated. Even the General commanding the Japanese forces at Rabaul interviewed him. Pappy later related in his memoirs titled “Baa Baa Black Sheep” that the General asked him who had started the war. After Pappy replied that of course, the Japanese had started the war by attacking Pearl Harbor, the General then told him this short fable:

“Once upon a time there was a little of old lady and she traded with five merchants. She always paid her bills and got along fine. Finally, the five merchants got together, and they jacked up their prices so high the little old lady couldn’t afford to live any longer. That’s the end of the story.” The General left the room, leaving Boyington to ponder that there had to be two sides to everything.

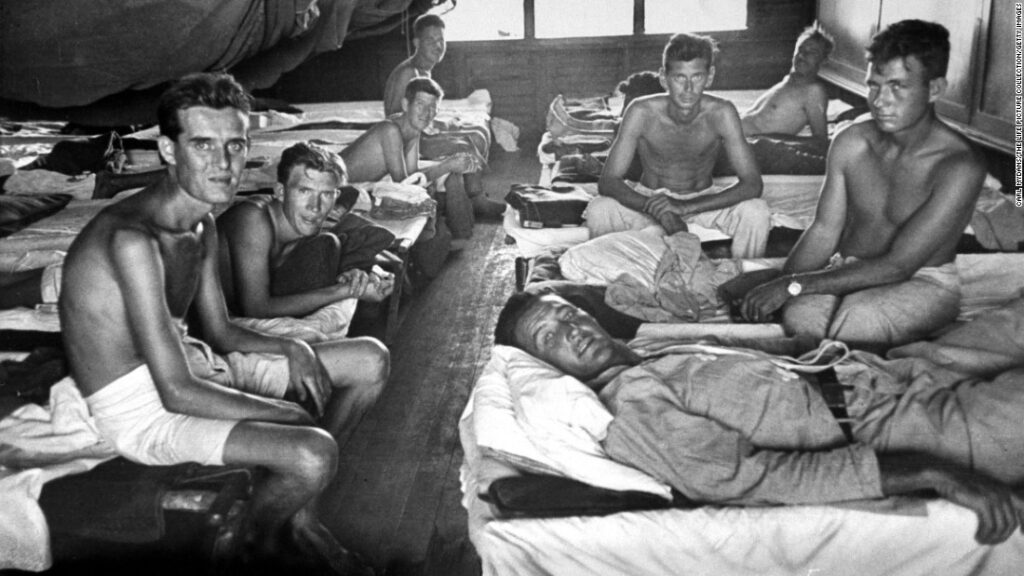

After about six weeks, the Japanese flew him to Truk. As he landed there, he experienced one of the early carrier strikes against Truk in February 1944. Along with six other captured Americans, he was confined in a small, but sturdy wooden cell which might have been designed for one inmate. The only opening was a six-inch hole in the floor, for relieving themselves. The stench became nearly intolerable.

He was eventually moved to a prison camp at Ofuna, outside of Yokohama. His autobiography relates the frequent beatings, interrogations, and near starvation that he endured for the next 18 months. The guards, whose only qualification seemed to be passing “a minus-one-hundred I.Q. test,” beat the prisoners severely for any infraction, real or imagined.

He initially lost about 80 pounds, and described how he once entirely consumed a “soup bone the size of my fist” in just two days, a feat which previously he would not have believed a dog could achieve. During the middle period of his captivity, he had the good fortune to be assigned kitchen duty. A Japanese Grandmother who worked in the kitchen befriended him and helped him filch food. Before long, he returned to his pre-captivity weight. He freely admitted later that during the two years he spent as a P.O.W. his health improved, due to the enforced sobriety, with one exception: on New Year’s Eve, he managed to get drunk after begging a little Sake from each of the Officers.

From Camp Ofuna, he witnessed the first B-29 raids striking the nearby Naval Base at Yokohama. During this time, he was given a temporary promotion to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. When he was repatriated, he found he had been awarded the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross. He also added to his claims for aerial victories after his return. Several other pilots had seen him down one Zero, which raised his total to 20 with the Black Sheep, and 26 if his claims for 6 with the Flying Tigers were included. Twenty-six was Eddie Rickenbacker’s WWI record, and the number shot down by Joe Foss, the top-scoring Marine pilot of all time.

Boyington is Highest Highest-Scoring ace in the Marine Corps

Back in the States, in September of 1945, he claimed to have shot down two more planes in that final battle. Frank Walton, the ACIO, prepared the combat report, and Gregory “Pappy” Boyington signed it. With a stroke of his own pen, Boyington was credited with twenty-eight victories, making him the highest-scoring ace in the Marine Corps. At the time, Boyington was being feted in a national War Bond Tour, patriotic feelings were running high, and he was a national hero. No one challenged the two additional claims.

Pappy lived until 1988, but it was a hard life, marked by financial instability, marriages and divorces, and battles with alcoholism. Things started downhill on his War Bond tour, when he was frequently drunk. On one infamous occasion, he embarrassed himself, the Corps, and the audience with a rambling drunken speech. His tangled affair with Lucy Malcolmson (still married to her husband Stewart Malcolmson) broke up, quite publicly, when he took up with Frances Baker, who became his second wife. Now a PR liability, the Marine Corps officially retired Gregory “Pappy” Boyington in 1947, allegedly for medical reasons, and promoted him to full Colonel.

The Success Boyington’s Autobiography, “Baa Baa Black Sheep.”

He moved from job to job, never able to stay with any one thing. He frequently refereed at wrestling matches. After a continued decline into alcoholism, he went on the wagon in 1956 and even joined AA. Things picked up for him in 1958 with the success of his autobiography, “Baa Baa Black Sheep.” He met Dee Tatum the next year, soon divorced Frances, and married Dee (his third). The 1960’s were a real low period for Pappy, including estrangement from his own children.

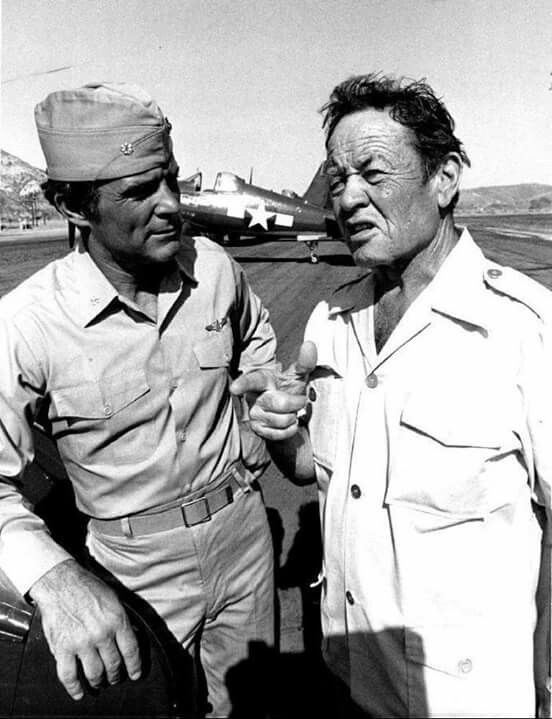

Pappy’s greatest fame came in the mid-Seventies when the television show “Baa Baa Black Sheep” appeared. Based very loosely on Boyington’s memoirs, the show had a three-year run, and achieved a consistent popularity in reruns. Pappy was a consultant to the show, and got on well with its star, Robert Conrad. But the show’s description of the Black Sheep pilots as a bunch of misfits and drunks, which Pappy happily went along with, destroyed Pappy’s friendship with many of his squadron veterans, including Frank Walton. The show made Pappy a real celebrity, found time to get married a fourth time to Josephine Wilson Moseman, and he made a good career out of being an entertainer – appearing at air shows, on TV programs, and other venues.

Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, who had been a heavy smoker and battled cancer since the ’60s, died in his sleep on January 11, 1988, at the age of 75 in Fresno, Calif.

Read About Other Profiles in Courage

If you enjoyed learning about Col Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, we invite you to read about other profiles in courage on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

0 Comments