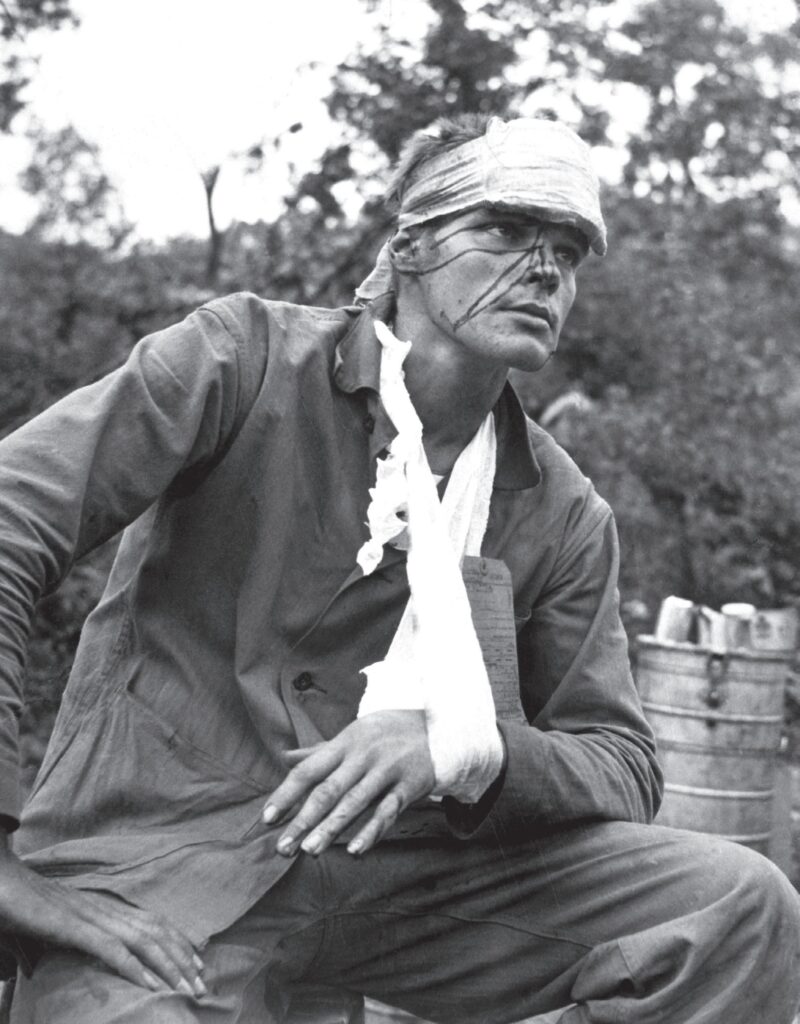

“There were 80 of us on that hill when an estimated 600-800 Chinese hit us hard that night. Sixty-six of us were killed, wounded or missing.”

PFC Edgar “Bart”Dauberman, USMC

“Easy”Company, 2d Battalion 5th Marines

In the spring of 1952, General James A. Van Fleet, USA, Commander, 8th United States Army in Korea and supreme commander of all Allied Forces in Korea, undertook one of the most audacious operations in the history of warfare. With his Army fully engaged against Chinese and North Korean communists across the Korean peninsula, General Van Fleet completely realigned his entire force. Dubbed Operation Mixmaster, thousands of men and vehicles and thousands upon thousands of tons of supplies and equipment were shuttled hundreds of miles to new positions over a period of more than one week. It was a daringly unprecedented operation, and the Chinese and North Koreans, who could have ruined it all, were caught flatfooted.

Hill Became the First Test of the Jamestown Line

For Major General John T. Selden’s First Marine Division, Operation Mixmaster meant a move across the width of Korea, from positions near Pohang on Korea’s eastern coast to a new location on the extreme left of the 8th Army line in the far west. From its new position on the Kimpo Peninsula west of Seoul on the Yellow Sea, the assigned sector of the 1stMarDiv stretched 32 miles eastward to the Samichon River, where it linked up with its “brother” division, the British Commonwealth Division. Thirty-two miles was an extraordinarily large stretch of front for a division to cover, but it was no coincidence that the two divisions were sited in such a manner. In planning the relocation of his forces, Gen. Van Fleet specifically directed what he termed “the two most powerful divisions in Korea”be positioned to block any Chinese attempt to access the Uijongbu Corridor, the traditional and natural geographic invasion route into South Korea.

One of 1stMarDiv’s first tasks in taking over its sector of the Main Line of Resistance (MLR), dubbed the Jamestown Line, was the establishment of a Combat Outpost Line (COPL) designed to break up any Chinese attack against the MLR. Most of these outposts were quickly, if unofficially, dubbed by Marines with names of famous motion picture and TV stars; Hedy, Dagmar, Marilyn, Esther and Ingrid, while others reflected names in the news: Siberia, Warsaw, Berlin and East Berlin. One of the first combat outposts received nothing more in the way of identification than a number, Outpost 3 (OP 3). It would be the scene of the first Chinese attempt to test the COPL, and while it was a small engagement in light of things to come, it would entail some of the heaviest fighting of the Korean War. There, on an otherwise insignificant hill, a small reinforced platoon of Marines withstood every attempt by two Chinese regiments to exterminate them and wrote a lasting tale of courage in their blood and steadfast resistance.

Outpost 3 Was Built Under Watchful Enemy Eyes

Before there was any shooting, however, there was a full ration of plain, old-fashioned, back-breaking work. Not an overpowering hill compared to the heights that confronted 1stMarDiv in the eastern region of Korea, OP 3 boasted an elevation of 400 feet. That, however, was the hill’s elevation above sea level. In tactical terms, the hill rose little more than 70 feet above the surrounding terrain. If not overpoweringly tall, the hill covered a good bit of ground, a very good bit of ground to be defended by a platoon, even a reinforced platoon. Nor did the hill possess even the most rudimentary of fighting positions. Every bunker, every weapons emplacement, every inch of trench line had to be dug and dug and dug.

The task of all this digging, manual hauling of timbers and filling of sand bags, fell to the 2d Platoon of Capt. Charles C. “Cary” Matthews’ E Company, 2d Battalion, 5th Marines (“Easy”/2/5). There would be a full ration of sweating, straining work and, while none of the platoon were aware of it, not overly much time to complete it. Watching them intently from concealed positions on the bulky hill mass of Taedok-San to their front, Chinese observers were following their every move. Farther to the rear, two entire regiments of the 195th Division, Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) 65th Army were making final preparations for what they intended to be the obliteration of the handful of Marines on OP 3. They would be supported by the fires of 10 artillery battalions fielding 106 guns, in calibers ranging from 76 mm to 152 mm and one battalion of self-propelled, high-velocity 76 mm direct fire guns, all courtesy of the Soviet Union.

Outpost 3 Faced a Massive Night Assault

As Tuesday, April 15, 1952, dawned over OP 3, Lieutenant Dean Morley, platoon leader of 2d Platoon of Easy/2/5, awakened to what appeared to be yet any other day, one he hoped would be uneventful. Throughout the day, Dean Morley got his wish. The Chinese continued to be relatively nonconfrontational. On OP 3, the Marines of the 2d Platoon contented themselves with making improvements to their positions, gnawing at C-rations, making small talk and speculating on when the battalion would be withdrawn to regimental reserve and the intriguing possibility that there might be a shower point set up. Two machine-gun squad leaders, Sergeant Arthur G. “Artie” Barbosa and Corporal Duane E. Dewey, made their usual daily checks of ammunition supply and marking stakes for principal direction of fire and final protective lines. In the 60 mm mortar section like routine preparations were undertaken. None of it was lackadaisical, and everything was done competently and professionally. There was no sense in getting caught with your skivvies at half-mast. All in all, though, it was just another day on OP 3.

That ended abruptly during the waning hours of April 15th. At 2330, a single green star shell was fired from the vicinity of Hill 67, which subsequent information would reveal to be the forward headquarters of the 195th CCF Division some 1,900 yards to the northwest. Everyone who was on watch on OP 3 saw it. Everyone back on the MLR saw it. Everyone knew what it meant. The Chinese were about to register their preparatory fires as a prelude to a major ground attack.

When the Chinese fire came, it came methodically and deliberately in the form of 76 mm howitzers and 122 mm mortars controlled by forward observers on Taedok-San. The Chinese, who tended to be quite skillful in these matters, raked OP 3 from front to rear and from side to side, concentrating their effort on key positions. The Marines of the 2d Platoon, who had sweated, strained and voiced their displeasure at all the manual labor that went into fortifying the hill, hunkered gratefully in the bunkers they had built as the ground about them rocked like an earthquake, fires lighting up the night sky with the brilliance of a fireworks display.

Amazingly, despite the intensity of the Chinese fire, there were no Marine casualties as the Chinese gave OP 3 a first-class working over. To Marines with an ear for such things, though, there was a disturbing uneasiness at the lack of any evidence of the presence of incoming 122 mm or 152 mm artillery rounds in the downpour of shells pummeling the position. That could mean but one thing: the Chinese were saving their heavy hitters for the main event. It wasn’t a comforting thought.

As suddenly as it had begun, the volcano of fire that engulfed OP 3 ended about 20 minutes later as another green star shell was fired from the same position as the first. No Marine on OP 3 had to be told what would be coming next. After an eerie quiet that lasted about five minutes, a third signal pyrotechnic fired once again from Hill 67 bathed the area out in front of OP 3 in a lurid green light which gave every tense face on the outpost an unsettling corpse-like tinge. No one had much time to contemplate that. Even before the illumination completely burned itself out, the Chinese, in what seemed to be inexhaustible numbers, came out of the dark and began moving toward OP 3.

When the Chinese came, they came in near mechanical waves, as though there were some manner of machine back behind Taedok-San grinding out rank after rank of automatons. If they were automatons, they were well-directed automatons, advancing implacably against the front and both sides of the Marines’ defensive positions. The entire perimeter erupted in a blaze of muzzle flashes as the defenders of OP 3 laid into the oncoming tide of Chinese with everything they had. It was a one-sided contest. There were too many Chinese and not enough Marines spread over too large an area.

Soon enough, the attacking Chinese had totally enveloped OP 3 on all sides and were firing into the defenders from every point of the compass. With more Chinese following close behind, some forced their way into the forward positions by sheer weight of numbers. In the process they gave Hospital Corpsman Second Class Jerome “Jerry” Natt a baptism of fire that would have been hard to duplicate.

Jerry Natt had joined Easy/2/5 shortly after noon that day and had been sent forward at dark to join the platoon on OP 3. Assigned to a bunker with two Marines and advised to get some sleep, he was told that he would get an orientation tour in the morning. The Chinese arrived first, and with them came casualties. Immediately there was the cry of, “Corpsman!” One of the first to send up that call was one of the Marines Natt had shared the bunker with to “get some sleep.”

The wounded Marine – Natt didn’t know his name – was outside in a firing position. It was as dark as the inside of a cat out there. The corpsman could only attempt to find the man’s wound by feel. Eventually, it was revealed to be a chest wound. Only because of the strobe-like light produced by incoming was Natt able to see well enough to stop the bleeding and put a dressing on the wound. Natt never forgot his abrupt “Introduction to Ground Combat 101,” nor did he ever learn the name of the first combat casualty he treated. There would be more.

Outpost 3 Was Held Through Extraordinary Acts of Valor

One among those was platoon leader Lt Morley, who went down hard hit (he would survive) and unable to continue. Lt Bill Maughan, a “short timer” due to depart in only several days, assumed command of the platoon. Maughan, a former enlisted Marine who had served in China before being commissioned, was immediately confronted by a problem, one that had been a disturbing possibility and was now a reality. Outpost 3 was too big an area to defend and there were too few Marines to adequately defend it.

Slowly, steadily, the defenders of OP 3, taking their wounded with them and keeping the Chinese at bay, withdrew into a tight perimeter in the southeastern corner of the hill. It was a barroom brawl every step of the way, Marines and Chinese locked into a welter of personal combat featuring rifle butts, fighting knives, entrenching tools and bare fists. They were getting help from the 81 mm mortars of Weapons Co, the 5th Marines 4.2-inch mortars back on the MLR and the 105 mm howitzers of Lieutenant Colonel James R. Haynes’ 1st Battalion, 11th Marines that pounded the Chinese relentlessly. Adding their voices to the symphony of explosives were the 155 mm howitzers of LtCol Bruce F. Hillam’s 4th Battalion, 11th Marines ranging farther back to punish Chinese assembly areas. It was not at all easy. Through rock-hard resistance and inspiring acts of personal courage beyond counting, the Marines established a defensible perimeter, but something had been left behind.

A member of the 60 mm mortar section was the first to notice it. A significant amount of 60 mm ammunition had been left behind. When you have both hands engaged in fighting the man who is attempting to kill you, there aren’t enough hands left over to tug along a crate of ammunition in the bargain. Another part of that bargain is the fact that a pair of 60 mm mortars are of scant use if there is no ammunition for them. Somehow that ammunition had to be retrieved by whatever means necessary. That was when Stanley “Stan” Wawrzyniak took over. Wawrzyniak, the company gunnery sergeant and no stranger to combat, had volunteered to accompany the platoon to OP 3 just to see if he could “help out.”

GySgt Wawrzyniak could smell a firefight from 5 miles off, and he couldn’t be paid to miss one. The situation on OP 3 looked promising. Already a holder of the Navy Cross for his valorous acts while “helping out” during the bitterly contested battle for Hill 812 in eastern Korea the previous fall, he proved once again his uncanny ability to be the right man at the right time. A man utterly without fear, he waded into the hail of incoming fire and swarming Chinese not once or twice but three times, returning each time with two cases of urgently needed ammunition. Being wounded during one of these forays didn’t stop him. After his final trip, he waved off medical attention to make a complete circuit of the new perimeter to direct the fires of individual positions. Only after that, did Wawrzyniak consent to allow a corpsman to stop the leakage of blood from two separate wounds. For his actions in the early morning hours of April 16, 1952, GySgt Stan Wawrzyniak would receive a gold star in lieu of a second Navy Cross.

(Author’s note: It was my good fortune to know LtCol Stan Wawrzyniak as a friend for many years until his death. He truly was that combat oddity, a man utterly without fear. Stan Wawrzyniak would not have backed off from an enraged gorilla.)

As chaotic as the situation on OP 3 was, it was not without one saving grace. For all the ferocity of the Chinese ground assault, that assault was not properly supported by artillery. Despite meticulously registering their fires on the positions of Easy/2/5 on the hill, when the Chinese infantry moved forward, the fires of the artillery were, for the most part, some 1,000 yards off target. While there was enough incoming on the hill itself to keep life from being dull and uninteresting, the bulk of the Chinese fires were falling off to the west at the time when they were most needed. Had some Chinese forward observer misread his map? Had the Chinese fire direction center incorrectly calculated elevation and deflection? Had someone erred in plotting the gun- target line?

Whatever the cause, it was enough to allow the defenders of OP 3 a few fleeting moments to catch their breath. As quickly as the Chinese attack had begun, it stopped, and the Chinese infantry withdrew to regroup before coming on again, this time properly supported by artillery.

While the first Chinese attack had approached tidal-wave proportions, the second Chinese attempt to wrest control of OP 3 struck like a human avalanche. By this time half of the defenders of OP 3 were dead or wounded. That didn’t prevent the wounded who still were capable of using a weapon, however, from using it to good effect. The Chinese were resolved to take the outpost. The Marines were even more resolved to hold it.

Hell was in session on OP 3, and machine-gun squad leader Sgt Artie Barbosa was suddenly fighting a one-man war. With his entire squad but one down, killed or wounded Sgt Barbosa manned the gun himself, laying withering streams of fire on Chinese attacking from two directions. As one after another of his squad fell, Barbosa, despite the deadly Chinese fire directed at him, single-handedly carried the machine gun and tripod to a position where it could enfilade both sides of the Chinese avenues of attack. Through his actions, Sgt Barbosa laid a carpet of dead Chinese at the points where the attackers came closest to breaching the perimeter.

While it cannot be said that any one man saved the day on OP 3, had Artie Barbosa not been there, the outcome of the firefight on OP 3 may have had a different ending. The Marine Corps felt the same way. For his courage and complete disregard for his own safety, Sgt Artie Barbosa would receive the Navy Cross. Rifleman Bart Dauberman, who lives today in Pennsylvania, still thinks it should have been the Medal of Honor.

If Artie Barbosa didn’t receive America’s highest award for military valor, Cpl Duane Dewey did. Duane Dewey, the squad leader of the other machine-gun squad that fought on OP 3, had his hands as full as anyone beating off what seemed to be a never ending supply of Chinese. Then a Chinese grenade landed alongside a corpsman who was caring for a wounded Marine.

Duane Dewey didn’t hesitate. He shoved the corpsman aside and threw himself atop the deadly device – after first putting his helmet over it. Incredibly, despite offering up his own life to save the lives of others, Cpl Dewey lived. One year later, fully recovered, Duane Dewey went to the White House where recently inaugurated President Dwight D. Eisenhower placed the blue ribbon of the Medal of Honor about his neck. Asked why he had first placed his helmet over the grenade that was about to detonate, he replied that he thought “maybe it wouldn’t hurt so bad.” Duane Dewey is made of tough stuff. He spends his time today in Florida and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. He still attends Easy/2/5 reunions.

There were courageous acts aplenty in a night that was torn apart by explosions and the never ending deadly roar of gunfire. One of the most courageous among those was the action of SSgt Quinton Barlow, the 2d Platoon’s platoon sergeant – he was the man who seemed to be everywhere at once. If there was any point at which the Chinese threatened to break through the perimeter, SSgt Barlow was there to pitch in and help beat it back. Moving from position to position amid a whiplash storm of incoming fire, Quinton Barlow went undeterred from one threatened point to another, giving no thought to his own safety, always managing to be in the most dangerous location. Quinton Barlow would become the third defender of OP 3 to receive the Navy Cross.

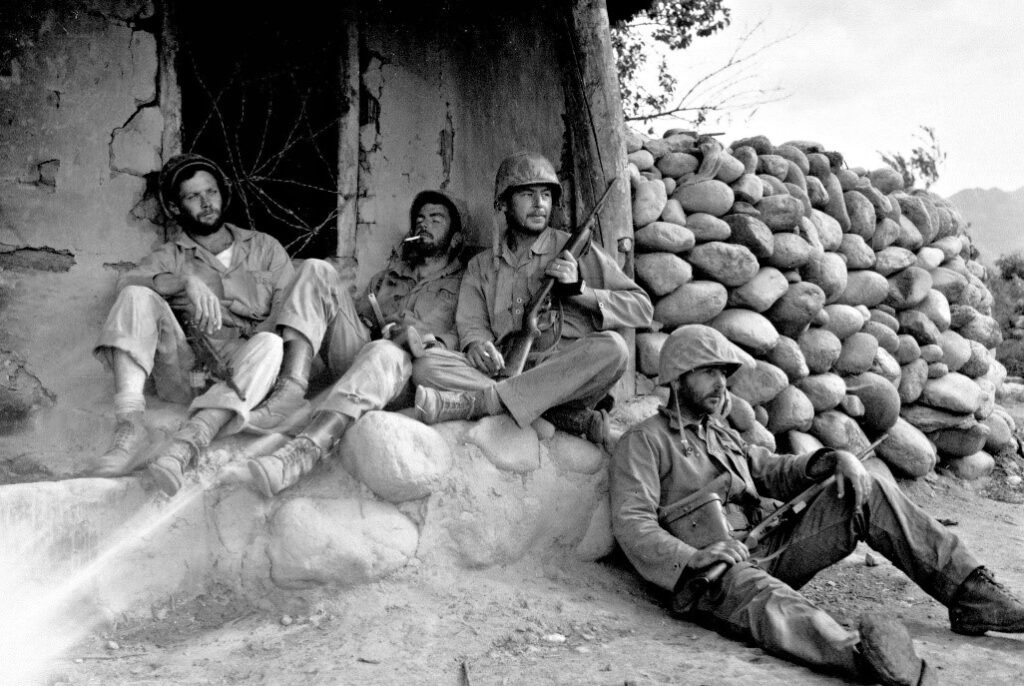

Almost as quickly as the firefight on OP 3 had begun, it ended. The Chinese attackers had met more than their match. Two entire regiments of Chinese never succeeded in their objective of wresting OP 3 from less than 100 Marines who intended to hold the hill or die on it. The sole Chinese who succeeded in breaking through that stalwart wall were three who were immediately overcome and taken prisoner. They seemed to be glad to be out of it.

At daybreak on April 16, the defenders of OP 3 were relieved. As they filed off the hill, they brought nine of their dead and 39 of their wounded with them. They brought as well one Medal of Honor, three Navy Crosses, six Silver Stars, four Bronze Stars and a basket full of Purple Hearts.

Has there ever been such an engagement in all of Marine Corps history, one in which so many testimonials to bravery and valor were showered on a single reinforced platoon? It would be interesting to find out.

Less than a week later, OP 3 was abandoned. The hill was simply too large to be defended by much less than a company, and the MLR could not spare a company for duty on an outpost. The war in Korea would go on and battles involving much larger units would be fought. Places with names such as Yoke, Bunker Hill, Ungok, the three Nevada Outposts (Reno, Carson and Vegas) and the Hook would all find their way into the record before the guns fell silent at Boulder City on July 27, 1953.

The firefight on Outpost 3, a minor engagement compared to the much larger battles in that war 65 years ago, would be forgotten, earning at most a page or two in Korean War histories. It would not be forgotten, however, by the Marines of Easy/2/5 who were there. They will gather one last time this summer, those who are still with us, men well into their 80s, to recall those long ago days and the men they shared them with. So many of those Marines of Easy/2/5 have answered their final roll call. After this last gathering, the proud banner that hung over their annual reunions will be presented to the 1stMarDiv for safekeeping, perhaps to serve as a testimonial to what rock-hard Marine resolve and Marine courage can achieve.

Author’s note: Deep gratitude and appreciation are owed MGySgt Leland “Lee” Brinkman, USMC (Ret) and Marine veteran PFC Edgar “Bart” Dauberman, Easy/2/5 Marines who were there, for their invaluable assistance in putting this narrative together.

Author Allan C. Bevilacqua is a former enlisted Marine who served in the Korean War and the Vietnam War, as well as on an exchange tour with the French Foreign Legion. Later in his career, he was an instructor at Amphibious Warfare School and Command and Staff College, Quantico, VA.

Reprinted with permission from the Marine Corps Association & Foundation, Leatherneck Magazine, May 2017

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the Firefight at Outpost 3, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

Mr. Bevilacqua asked “Has there ever been such an engagement in all of Marine Corps history, one in which so many testimonials to bravery and valor were showered on a single reinforced platoon? It would be interesting to find out.” I would submit that the heroism exhibited by the 18 Marines and Navy Corpsmen with GySgt Jimmie Earl Howard on Hill 488 in June 1966 in Vietnam is certainly comparable if not indeed exceeds that of Easy/2/5. When they were finally relieved each and every one of those incredibly brave men had been killed or wounded. Their valor was recognized by the awarding of the Medal of Honor to Gunny Howard and to his men four Navy Crosses, thirteen Silver Stars, and eighteen Purple Hearts.

Semper Fi Easy 2/5

Semper Fi to all of Easy 2/5. My biggest problem was giving it up after giving so many lives in keeping it. It happen too many times in Vietnam. I am proud to say they were my brothers fighting over there in the Marine Corps. I did have 2 brothers that fought in the Korean War in the Army and one reenlisted for a second tour. He was awarded the Bronze Star and now the records of their service were burnt in a fire in Saint Louis, Mo a few years back. I sent for his awards and records with all the information that I have and they refused to reissue any. So I must say, protect all records that you have of your family in case you need it in the future. Thank all of the Marines and all service men for their Service and Commitment to their branch of service and to our country. Thank You