By the summer of 1951, the Korean War had reached a stalemate as peace negotiations began at Kaesong. The opposing armies faced each other across a line which ran with many twists and turns along the way from east to west, through the middle of the Korean peninsula, a few miles north of the 38th parallel. UN and communist forces jockeyed for position along this line, clashing in several relatively small but intense and bloody battles.

The First Bloody Ground Battle

One bloody ground battle took place from August 18 to September 5, 1951. It began as an attempt by UN forces to seize a ridge of hills which they believed were being used as observation posts to call in artillery fire on a UN supply road.

It was a joint operation conducted by South Korean and the U.S. Army’s 2nd Division. Their mission was to seize a ridge of hills used by the North Koreans as observation posts to call in artillery fire on a UN supply road. Leading the initial attacks was the 36th ROK Regiment. It succeeded in capturing most, but not all, of the ridge after a week of fierce fighting that at times was hand to hand. It was a short-lived triumph, for the following day the North Koreans recaptured the mountain in a fierce counterattack.

The next assault was made by the 9th Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Division. The battle raged for ten days, as the North Koreans repulsed one assault after another by the increasingly exhausted and depleted U.S. forces. After repeatedly being driven back, the 9th succeeded in capturing one of the hill objectives after two days of heavy fighting. The weather then turned to almost constant rain, greatly slowing the attacks and making operations almost impossible because of the difficulty in bringing supplies through “rivers of mud” and up steep, slippery slopes.

Fighting continued, however, and casualties mounted. The 2nd Division’s 23rd Infantry Regiment joined the attack on the main ridge while the division’s other infantry regiment, the 38th Infantry Regiment, occupied positions immediately behind the main ridge which threatened to cut off any North Korean retreat. The combination of frontal attacks, flanking movements and incessant bombardment by artillery, tanks, and airstrikes ultimately decided the battle. Over 14,000 artillery rounds were fired in a 24-hour period. Finally, on September 5, 1951, the North Koreans abandoned the ridge after UN forces succeeded in outflanking it.

The American soldiers called the piece of terrain they had taken “Bloody Ridge.” which indeed it was: 2,700 UN and perhaps as many as 15,000 communists were casualties, almost all of them killed or wounded with few prisoners being taken by either side. The much higher communist casualties were probably caused by poor discipline in the KPA and constraining orders so strict to the point where subordinate leaders were often not allowed to withdraw under any conditions, in which case the entire unit would be blooded. Even when permission was granted for a withdrawal, it often came only after the large majority of troops in the unit had been killed.

After UN forces withdrew from Bloody Ridge, the North Koreans set up new positions just 1,500 yards away on a seven-mile-long hill mass that quickly earned the name “Heartbreak Ridge.”

One of Several Major Engagements in The Hills of North Korea

The month-long battle took place between September 13th and October 15th, 1951and was one of several major engagements in the hills of North Korea a few miles north of the 38th parallel-the pre-war boundary between North and South Korea.

If anything, the Communist defenses were even more formidable here than on Bloody Ridge. The U.S. 2nd Infantry Division’s acting commander, Brig. Gen. Thomas de Shazo, and his immediate superior, Maj. Gen. Clovis E. Byers, the X Corps commander, seriously underestimated the strength of the North Korean position.

They ordered a single infantry regiment, the 23rd, and its attached French Battalion, to make what would prove to be an ill-conceived assault straight up Heartbreak’s heavily fortified slopes.

All three of the 2nd Division’s infantry regiments participated, with the brunt of the combat borne by the 9th and 23rd Infantry Regiments, along with the attached French Battalion.

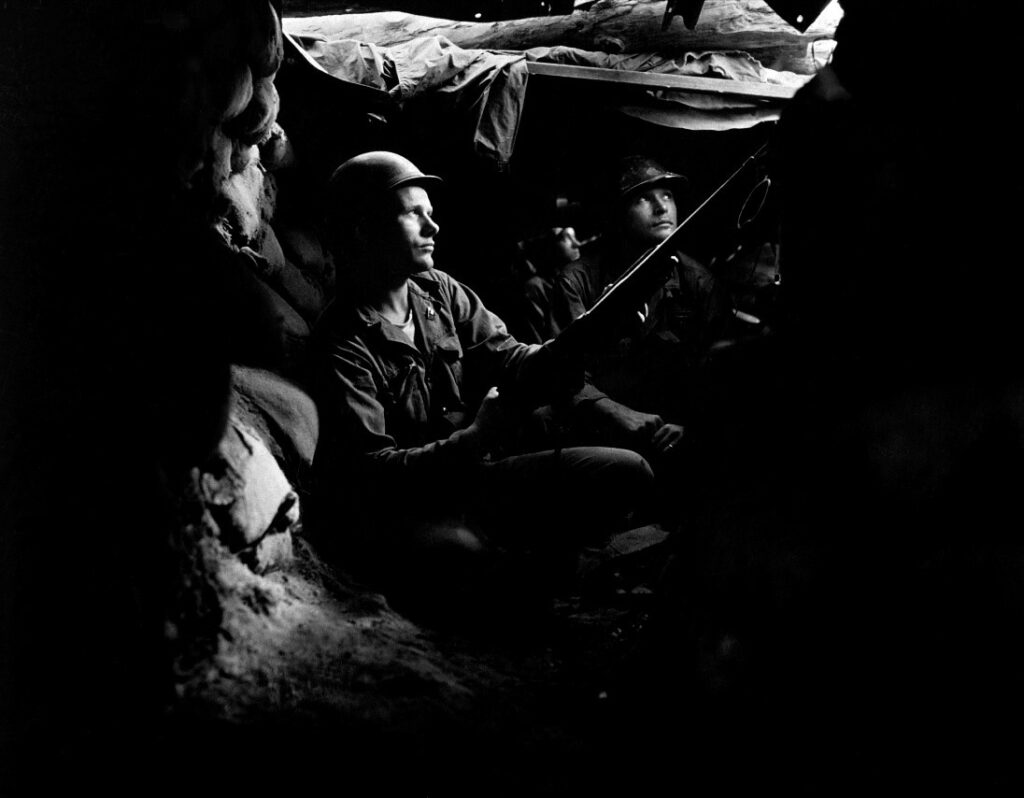

The initial attack began on September 13th and quickly deteriorated into a familiar pattern. First, American aircraft, tanks, and artillery would pummel the ridge for hours on end, turning the already barren hillside into a cratered moonscape. Next, the 23rd’s infantrymen would clamber up the mountain’s rocky slopes, taking out one enemy bunker after another by direct assault. Those who survived to reach the crest arrived exhausted and low on ammunition. The inevitable counterattack soon came-waves of North Koreans determined to recapture the lost ground at any cost. Many of these counterattacks were conducted at night by fresh troops that the North Koreans were able to bring up under the shelter of neighboring hills. Battles begun by a bomb, bullet and shell were inevitably finished by grenade, trench knife and fists as formal military engagements degenerated into desperate hand-to-hand brawls. Sometimes dawn broke to reveal the defenders still holding the mountaintop.

The battle progressed for two weeks. Because of the constricting terrain and the narrow confines of the objectives, units were committed piecemeal-one platoon, company or battalion at a time. Once a unit could no longer stand the strain a replacement would take its place until the 23rd Infantry as a whole was fairly well shattered.

Several units up to company size of 100-200 men were wiped out. The Americans employed massive artillery barrages, airstrikes, and tanks in attempts to drive the North Koreans off the ridge, but the KPA proved extremely hard to dislodge.

Finally, on September 27th the 2nd Division’s new commander, Maj. Gen. Robert N. Young, called a halt to the “fiasco” on Heartbreak Ridge as American planners reconsidered their strategy.

Renewed Assault in the Battle Of Heartbreak Ridge

As long as the North Koreans could continue to reinforce and resupply their garrison on the ridge, it would be nearly impossible for the Americans to take the mountain. After belatedly recognizing this fact, the 2nd Division crafted a new plan that called for a full division assault on the valleys and hills adjacent to Heartbreak to cut the ridge off from further reinforcement. Spearheading this new offensive would be the division’s 72nd Tank Battalion, whose mission was to push up the Mundung-ni Valley west of Heartbreak to destroy enemy supply dumps in the vicinity of the town of Mundung-ni.

It was a bold plan, but one that could not be accomplished until a way had been found to get the 72nd’s M4A3E8 Sherman tanks into the valley. The only existing road was little more than a track that could not bear the weight of the Shermans. To make matters worse, the road was mined and blocked by a six-foot (2 m) high rock barrier built by the North Koreans. Using shovels and explosives, the men of the 2nd Division’s 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion braved enemy fire to clear these obstacles and build an improved roadway. While they worked, the division’s three infantry regiments-9th, 23rd and 38th-launched coordinated assaults on Heartbreak Ridge and the adjacent hills.

By October 10 everything was ready for the main operation. On October 11th, led by more than 30 tanks and supported by artillery and airplanes, the 2nd Division started advancing into the valley. The sudden onslaught of a battalion of tanks racing up the valley took the enemy by surprise. By coincidence, the thrust came just when the Chinese 204th Division was moving up to relieve the North Koreans on Heartbreak Ridge. The Chinese unit under fire was the 610th Regiment of the 204th Division (Commander: Wenfang Luo), dispatched by the 68th Army (Commander: Niansheng Wen). The regiment’s mission was to reinforce the North Korean defense along the valley against a possible American armored offensive; more specifically, it was ordered to prevent the Americans from reaching the town of Mundung-ni at all costs.

Before the Chinese could dig in, the 2nd Division had already started the attack. Caught in the open, the Chinese division suffered heavy casualties from the American tanks as the armored vehicles penetrated to a depth of 6 km of the Chinese defense lines and caused great damage. However, the 610th Regiment managed to damage five Sherman tanks before the Americans halted the offensive.

On October 12th the 2nd Division began an airborne and artillery bombardment that lasted for two hours on Hill 635 and Hill 709 before the 23rd Regiment, led by 48 tanks, assaulted Chinese defensive positions. Having learned the American tactics from the previous day, the 610th Regiment of the Chinese army had already reinforced the anti-tank trenches flanking the road that runs through the Mundung-ni Valley; in addition, a battalion of anti-tank guns was assigned to the regiment (49 infantry guns, recoilless guns, and rocket launchers were also distributed among the front-line soldiers.) At point-blank range, the Chinese soldiers fired upon the advancing American tanks. Before the 23rd halted the assault at 4 pm, the Chinese had destroyed or damaged 18 tanks.

The 23rd Regiment did not assault the hills on the next day. The South Korean 8th Division, however, starting from October 13, launched its attack on hills 97, 742, 650, 932 and 922. These battles were subsequently known to be brutal and costly; for example, a company of the Chinese 610th Regiment was defending hill 932. Under the attack of four South Korean battalions, the company resisted for four days to the last man before the South Korean army took the hill on its 11th assault.

On October 14th eight Sherman tanks in arrow formation attacked the Chinese positions along Mundung-ni Valley. All the tanks were knocked out by the crossfire of Chinese anti-tank guns. Two more were lost on October 19th due to mines. During the five days, the Shermans roared up and down the Mundung-ni Valley, over-running supply dumps, mauling troop concentrations and destroying approximately 350 bunkers on Heartbreak and in the surrounding hills and valleys. A smaller tank-infantry team scoured the Sat’ae-ri Valley East of the ridge, thereby completing the encirclement and eliminating any hope of reinforcement for the beleaguered North Koreans on Heartbreak Ridge.

The armored thrusts turned the tide of the battle, but plenty of hard fighting remained for the infantry before French soldiers captured the last communist bastion on the ridge on October 13th.

The Aftermath of the Battle Of Heartbreak Ridge

After 30 days of combat, the Americans and French eventually gained the upper hand and secured Heartbreak Ridge. Yet the Sherman tanks did not penetrate through the Mundung-ni Valley and reach the town of Mundung-ni after 38 of the armored vehicles were destroyed and nine were damaged. The defense of the Mundung-ni Valley (or as it is known today in North Korea, the Battle of Height 1211) is today celebrated as a great victory in North Korea, with a claim of a total of 29,000 enemy casualties (certainly inflated), 60 tanks destroyed and 40 airplanes shot down: North Korean propaganda today enhances the defense of the heights around the valley and a number of significant acts of courage and sacrifice (real or alleged) committed during the battle. Actually, the failure of the Allied offensive inside the valley and the heights above gave to the North Korean Army one of the few victorious actions during the last phase of the war.

Both sides suffered high casualties-over 3,700 American and French and an estimated 25,000 North Korean and Chinese. These losses made a deep impression on the UN and US command, which decided that battles like Heartbreak Ridge were not worth the high cost in blood for the relatively small amount of terrain captured.

However, the UN offensives were to continue with equally high casualty rates for the 1st Cavalry in Operation Commando, and the 24th Division in Operation Nomad-Polar, which was the last major offensive conducted by UN forces in the war.

Public opinion had by this time turned against “limited-objective” operations of this nature, and military censorship resulted in far less media focus on the other October battles that followed Heartbreak Ridge.

Heartbreak Ridge is regarded as a good illustration of simple lessons. First among them as in World War I and World War II, simply using tremendous quantity of firepower did not guarantee victory in mountainous terrain. For attacks to succeed, attacks had to be made on a large scale and combining maneuver where possible. Even then attacks in the mountains would be a slow and laborious process, even where the enemy was vastly outnumbered and suffering grotesquely disproportionate casualties. In this sense what Heartbreak Ridge also showed was that the U.S. Military could be amazingly stubborn about having to re-learn the same lessons over and over again.

In the case of Heartbreak Ridge, it emerged as the consequence of an earlier, also bloody battle for the aptly named Bloody Ridge, where lightly-armed Communist troops used terrain to negate some of the effects of UN firepower, and relied chiefly on stubbornness and willpower to protract the fighting in this first stage.

In spite of the fanatical nature of the Communist resistance on Bloody Ridge, UN troops assigned to Heartbreak Ridge which consisted initially of a U.S. infantry regiment and a French battalion to capture this ridge. Against them were dug in a large number of far more lightly armed North Korean and Chinese troops.

The result was that the UN forces prepared a full-strength divisional attack on the ridge, using concentrated armor in an attempt to outflank the North Koreans. By this time the Chinese were preparing to send their own reinforcements, which is one of those chance co-incidences possible in warfare collided with UN troops which had managed to clear means through a minefield-ridden defensive position for the armored strikes to start pushing through.

At the same time, UN infantry forces began what proved to be an unpleasantly slow, slogging drive against a primarily North Korean defense. The Chinese troops, unpleasantly for them but happily for the UN got caught in the open by the armored detachment, were massacred, but the UN found that mountains canalize armor, and from this one incident at the start came far more slow, steady slogging of air, infantry, and armor that would finally take Heartbreak Ridge at the close of a month’s worth of major combat, between September and October of 1951. The result was an increasing tendency among UN troops to decide that such costly battles, with a sum total of 3,700 UN troops (as opposed to 25,000 Communists) were not a good augur for any kind of significant breakthrough operation.

Editor’s Note: A well-written story of one man’s experience on Heartbreak Ridge gives a personal account on what it was like to fight in this bloody battle. He is Sgt. 1st Class Bill Wilson who served as a Platoon Sergeant in Company I, 23rd Regiment 2nd Division U.S. Army during the Ridge.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the battle of Heartbreak Ridge, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

0 Comments