In stark contrast with the mission of combat forces, the US Army Medical Corps are committed to providing aid and comfort to the injured: wounded soldiers, civilians and at times even enemy personnel. There are no medals, no glory, and heroism is measured in blood, sweat and tears. Though the Korean War has been regarded as a failure by many because of its indecisive outcomes, in one area it was an unbridled success-saving lives. When the war broke out in Korea on June 25, 1950, there were only two hundred doctors in the entire Far East Command (Japan, Guam, the Philippines, and Korea). To ensure combat medical services, Congress quickly passed the Doctors Draft Act, requiring all doctors under the age of fifty-one to register for military service. As a result, ninety percent of all staff doctors in Korea were draftees, displaying a more relaxed attitude about Army rules, regulations, and discipline. At this same time, the Army authorized new medical procedures and deployed groundbreaking methods for transport and treatment of the injured, effectively reinventing combat care. One such development was the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) popularized by Dr. H. Richard Hornberger in his 1968 best-selling book (MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors), subsequent movie, and television series based on his real-life experience with the MASH 8055th.

MASH 8055th Deployed Groundbreaking Methods for Transport and Treatment of the Injured

In World War II, the fatality rate for seriously wounded soldiers was 4.5 percent. In the Korean War, that number was cut almost in half, to 2.5 percent. That success is attributed to a combination of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, or MASH unit, and the aeromedical evacuation system comprised of the casualty evacuation (casevac) and medical evacuation (medevac) helicopters. Comprised of a series of tents and buildings that could be easily relocated as the front lines moved, the MASH units moved with them to keep the units as close to the front as possible. To accomplish this, accommodations were stark, with operating tables formed by a stretcher balanced across two sawhorses.

In past conflicts, wounded soldiers often had to wait hours to be treated but thanks to the MASH units and the helicopters that brought in the wounded, the wait time was reduced to minutes. As the centerpiece of the Army’s medical innovations these mobile units were fully self-contained, working hospitals, first conceived in 1945 at the close of World War II and the brainchild of Dr. Michael DeBakey. Aside from the constant stress of warfare and long hours in surgery, the units usually picked up and moved at least once a month which came to be known as “bugging out”. Specifically, standards for a MASH required that it was disassembled, loaded onto vehicles, and ready to depart on a six-hour notice. After arrival at its new destination, it was operational within four hours.

In Korea, US soldiers wounded at the battlefront were first attended to on site by medics and doctors attached to their unit. If the injuries were serious, the men were then evacuated to a MASH unit for surgery and recovery. If warranted, the soldiers were evacuated to a larger hospital for treatment and if very serious, sent home from there. Initially limited to 60 beds to focus on mobility, with only seven MASH units in Korea (MASH 8054th, MASH 8055th, MASH 8063rd, MASH 8076th, MASH 8209th, MASH 8225th, and MASH 8228th) the hospitals were often overwhelmed with wounded and enlarged to 150 beds in November 1950, and again in May 1951 to 200. With the Doctor’s Draft Act of 1950, the timing of this expansion worked well for draftees that began to arrive in January 1951.

Similarly, about 540 nurses served tours of duty on the Korean peninsula. Though women weren’t allowed on the front lines in combat roles these nurses served close to the front lines and sometimes in the line of fire. In fact, by the end of the war Army nurses had received 9 Legions of Merit, 120 Bronze Stars, and 173 Commendation Ribbons.

The Korean War Provided an Opportunity to Test Helicopters

Much like MASH units, in the early 1950s the helicopter was still in its infancy. A few made an appearance in the last days of World War II, but now they would be tested on the front lines in Korea. The helicopters carried no guns; they were equipped only with exterior pods and stretchers to extract wounded from the battlefield. They were fragile, high-maintenance aircraft with limited range. The early models had no radio or instrument lights in their cockpits. They couldn’t operate in bad weather, were limited on where they could land, and were fatally vulnerable to enemy ground fire. In January 1951, four aeromedical evacuation helicopter detachments arrived in Korea, medevacs that would transport more than 20,000 casualties during the war, with one pilot (1st Lt. Joseph L. Bowler) setting a record of 824 medical evacuations over a 10-month period. Perhaps a measure of the helicopter’s impact is evident with the successful evacuation of 750 critically wounded soldiers in one day, Feb. 20, 1951, half of whom would have died according to one surgeon if only ground transportation had been used. Once the choppers arrived with their wounded, the medical teams unloaded the patients and prepared them for surgery. “There were times when the medical personnel were overloaded, so the pilots would help bring in the wounded and even help the doctors with instruments from time to time.”

Richard Kirkland had always wanted to fly, a dream he’d had since he was a young boy. During World War II he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and was about to deploy as a member of the 3rd Rescue Squadron flying helicopters. On one of his first nights in Korea he was introduced to many of the doctors and nurses of the MASH 8055th. There Richard was befriended by two men who would later be commemorated in print and inspire generations through film and television. “One of the surgeons shook hands saying, ‘They call me Hawkeye- welcome to MASH. The M stands for mud.’” This, of course, was Dr. Hornberger who later wrote about his experience with the MASH 8055th under the pen name Richard Hooker. A second tent mate, Capt. Michael Johnson, was the basis for the character Trapper John. In Korea, Hornberger pioneered a kind of surgery that was prohibited during the war. “Hornberger possessed the courage and audacity to attempt arterial repair when it was forbidden, and by one account, he may have been the first.” Despite the rules and encouraged by early success, with the routine use of vascular surgery during the Korean War doctors reduced the amputation rate resulting from vascular injury to 20.5 percent from 49.6 percent during World War II.

In a broad sense, with MASH units in-place the Korean War provided an opportunity to study and test new equipment and procedures, many of which would become standards of care in both military and civilian medicine; vascular reconstruction, artificial kidneys, improved cold weather treatments, the newest antibiotics, and other drugs (anticoagulant heparin, sedative Nembutal, serum albumin and whole blood to treat shock) that advanced medical care. In addition, computerized data collection (in the form of computer punch cards) and the use of plastic bags for the transport and handling of blood- a method later adopted around the world and still used today.

Life in a MASH unit varied greatly between boredom and endless hours of surgery due to overwhelming casualties. During a “push” (offensive front-line action) the wounded streamed into the operating room for days. Otto Apel, a MASH doctor, remembers, “Seventy-two hours after I had arrived at MASH 8076, I had lost the sense of feeling in my feet. I do not think I had spoken to anyone … for at least twelve hours.” Dr. Apel it turned out, had performed non-stop surgeries for eighty hours upon his arrival. Harold Secor, surgeon for the MASH 8055th recalls that staffing was lean, perhaps thirty corpsmen, ten doctors, ten nurses, one dentist, two service corps officers, and about thirty Koreans. Compounding matters was the units’ proximity to the front line. The MASH 8055th was generally four to five miles behind the front lines and according to Dr. Secor, “If they pulled back very far, we were on the enemy side, that happened at least once. We had a mine field in our front yard. There was always some danger, even from our own artillery firing over us. We had sandbags around the patient tents to stop stray bullets”. Secor remembered that one day, “a bullet zinged into the mess tent, hit a post, and splashed into a cup of coffee”. He said, “This was one of the accepted things that it didn’t pay to dwell on”.

Harold Selly was an Army medic, part of a forward collecting station team. “We were always in danger of being attacked or overrun by the enemy, shelled by artillery and mortars, and grenades thrown into the station,” he recalled.

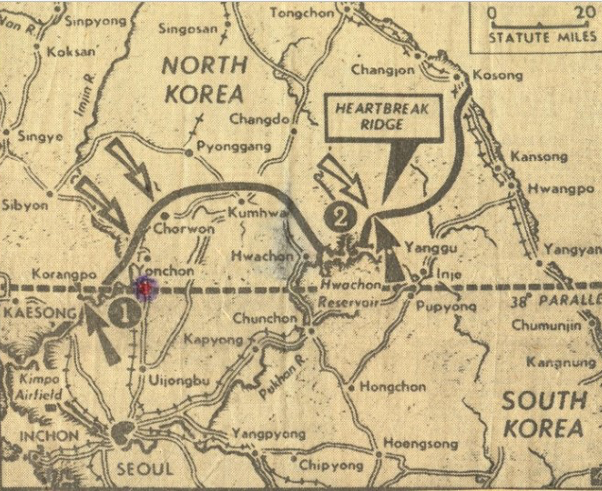

As United Nations (U.N.) troops crossed the 38th parallel and advanced north in the fall of 1950, they encountered a civilian population decimated by epidemics of typhus, smallpox, and typhoid. In addition, captured North Korean, and later, Chinese troops were ill with these and other contagious diseases. But most troubling was mentions of men turning black as they died, suggesting bubonic plague – the Black Death – was in Korea. But as it turned out, the plague was actually a virulent form of smallpox known as hemorrhagic smallpox. As a result, the 8228th MASH was established for the sole purpose of eradicating these diseases among enemy and civilian populations.

MASH’s 8055th Helicoppter Evacuations Became the Standard for Wars

By late 1951, the front line stopped moving and for the most part remained in-place until the war was over in 1953, negating the need for hospital mobility. Accordingly, the MASH units were replaced with smaller, more efficient combat surgical hospitals (CSH) and forward surgical teams (FST). At the turn of the twenty-first century there was only one MASH unit left in the world, in Albania, the last to be deactivated in February 2006. Nonetheless, MASH units and the helicopter evacuations developed during the Korean War became the standard for operations in Vietnam, and later Operation Iraqi Freedom. The visionary surgeon and inventor Dr. Debakey went on to become renowned for pioneering developments including coronary bypass operations, carotid endarterectomy, artificial hearts and ventricular assist devices, grafts to replace or repair blood vessels and surgical repairs of aortic aneurysms, receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the National Medal of Science, and the Congressional Gold Medal. Despite this acclaim, perhaps the most remarkable contribution centered on a brief and often forgotten moment in time, in a faraway land, where citizen surgeons and nurses gathered to defend freedom, advance medical science, and risk everything to save lives.

Read About Other Famous Military Units

If you enjoyed learning about 8055th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (Mash), we invite you to read about other Famous Units on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

One of Dr. Hornberger’s tent mates was Dr. Agrippa (“Grip”) Kellum. Dr. Kellum was mine and my family’s doctor in the 50’s and early 60’s in Tupelo, MS.

My Family Doc in the 80’s was Leon Meyer a Tulane Grad. He smoked a pipe, wore Hawaiian shirts, his 2 seater car had a custom CA plate “DANGER” spent lunch in a concrete flood control canal practicing fly casting. When I told him I was in a Reserve unit on the Presidio SF he told me to never need him on the weekend as he was drunk.

While attending product training schools several of us hired at the same time began showing up at the same schools. 1 guy tells us he married to a Korean lady who’s father worked at the MASH and had a unit photo. He brings and we pass it around after he pointed out the author. In the front row is my 5’4″ Doc. When I tell him about it he he takes a puff off the pipe and asked if I had a copy. No I did not. He takes another puff nodding his head and say “to bad”.

After he sold his practice he did time a Navy off site Clinic. My Mother in Law was seen by him. I guess she bragged about her 4 grandchildren and told us what a nice man he was.

AwhiIe back looked up his name and found a obit. It stated he had received a Bronze Star for pulling 6 men out of a crashed Helo. Retirement allows me the time.

Does anyone know my mom, Ruth (Bellany) Garberg? She was a nurse with the 8055.

The operating room nurse in that picture is Captain Elmira Dalrymple. She is my aunt. She went on to become Major Elmira Dalrymple. She retired after serving in three wars. Since she never had children, I am piecing together her story. Does anyone remember Elmira known as Dal.

Hi, Brenda, I’m researching women in the Korean War. Do you know which MASH your aunt served in?

Hi

Could you please contact me – looking for Korean War Mash nurses for AARP piece.

Thanks

alex kershaw

310 386 7505

Hi Alex. My mom was a nurse in a mash unit. I think the 8055. Ruth (Bellany) Garberg.

Pearce Hawk

661 425 8607

I remembering walking into our post clinic and you see a mural with the cast of M.A.S.H. That was Camp Humphreys, pyeongtaek, Korea in 1990.

My grandfather was Dr. Harold C. Stricker from Jefferson City Missouri. He served in a MASH hospital in Korea, but would never talk about his service. I do not know which unit he served with or his dates of service. Does anyone remember serving with him that can shed some light on his experiences for us? Thank you!

My father also served as a physician in a MASH unit, and likewise never spoke of his time there. Couldn’t imagine what they witnessed.

My father in law Dr. Tom French Little was a Tulane Univ. trained medical doctor in the US Army Eight Division. in Korea. Dr. Tom was from Ocilla, Georgia . Dr. Tom went to Africa with the 2nd Armored Division . then to England and Normandy attached to the 66th Armored Regiment. He ended his military service in Korea as a Lt Col.in a Mash unit. I have his two bronze stars that he was awarded. He was on the front lines in Europe and he told me that a sniper almost got him and I still have his helmet with the bullet crease and the cut netting on the top. This is the only information that he ever mentioned about WW11.

My name id SSG (CA) James Yellis, I am the Curator of the 40th Infantry Division Headquarters Museum here in Loa Alamitos, Ca.

I was wondering if there is a list or some information as to what M*A*S*H Unit took casualties from the 40th ID. We would like to Honor those surgical Members in our Museum

If anyone knows my grandfather Monroe Jennings, he served as a medic in the Korean conflict in Korea and Japan I believe. Feel free to contact me.

My father James Foley was the x-ray tech in the Mash 8055 unit. He passed St. Patrick’s Day,March 17, 2004 in Tampa Fl. We used to watch Mash together. Wonderful man. I miss him still.

My wife’s uncle, D.E. Susong, spent a short time in Korea as a operating room tech in the 8055.

Newspaper.com “Greeneville Sun, 10/25/51, page 9”

DE’s brother who served at the same time ended up being the doc when he returned stateside and received his training. I never got a chance to ask DE to tell a story, if he had wanted to.

I believe my Dad was a combat medic in this unit… he was interviewed for the movie MASH 4077… I’m looking for any information I can get…. Sergeant Billy Mask

I went on a helicopter tour in Hawaii on the Island of Kauai and, while waiting for our ride, we heard over the radio that a helicopter had crashed on the north shore of the island (different tour company). But so that people didn’t freak out and demand refunds, they told us we had a treat and we got perhaps the single most experienced helicopter pilot in existence. He flew H-19’s in Korea for MASH units and he could do some things with a helicopter that nobody else could (I worked offshore in the oilfield so I rode in helicopters a lot). This guy was the best. His skin looked like he was made from an old leather boot. He must have been in his 80s (back in 2004) Sharp as a tack.