On Sunday, June 25, 1950, just before as sunrise, South Korean soldiers and their American advisors awakened to what they expected to be just another routine day guarding the demarcation line separating South Korea from Communist North Korea. Instead, they woke up to North Korean artillery blowing apart their positions, followed by heavy tanks and thousands of screaming North Korean soldiers. Outnumbered and outgunned, the UN forces were powerless to rout the invaders, forcing them into a disorderly withdrawal south.

Never able to get their footing, UN forces continued moving south down the Korean peninsula, fighting delaying actions in Seoul, Osan, Taegu, Masan, P’ohang, and the Naktong River. Their withdrawal took nine days, ending at the southeastern-most tip of South Korea near the port city of Pusan on the Sea of Japan. Exhausted and on the brink of defeat, they hurriedly set up the ‘Pusan Perimeter’ to make their final stand against the determined North Korean army.

Fighting was fierce and bloody all along the entire perimeter from August 4 to September 18, 1950. North Korean troops, although hampered by supply shortages and massive losses, continually staged attacks on UN forces in an attempt to penetrate the perimeter and collapse the line. UN forces held on while using the port to amass an overwhelming advantage in troops, equipment, and logistics from numerous UN combatants. After six weeks and fighting small skirmishes and large battles, the North Korean force collapsed and retreated back north in chaos with UN forces in pursuit.

Many historians considered the Battle of the Pusan Perimeter one of the most brutal fights of the Korean War where both sides endured major losses: U.S. forces suffered 4,599 dead, 12,058 wounded, 401 captured and 2,700 missing in action. North Koreas had a total of 63,590 casualties and 3,380 captured.

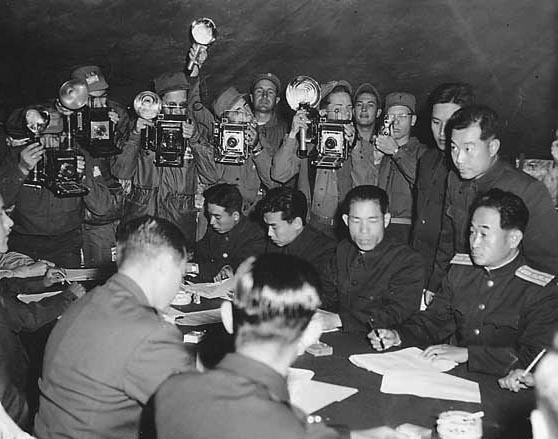

In September 1950, an amphibious UN counter-offensive was launched at Inchon, cutting off many of the North Koreans soldiers retreating north. Those that escaped envelopment and capture were rapidly forced back north all the way to the border with China at the Yalu River, or into the mountainous interior. At this point, in October 1950, Chinese forces crossed the Yalu and entered the war. Chinese intervention triggered a retreat of UN forces which continued until mid-1951. During this time, the front lines constantly changed as each side gained the upper hand over the other. Realizing that neither side would be able to overcome the other, the combatants met in July 1951 at the village of Kaesong to begin armistice negotiations. In October 1951, the meeting was moved to Panmunjom.

By 1953, while the leaders of the People’s Republic of Korea and Communist China continued deliberating with UN delegates in peace talks at Panmunjom, their soldiers continued to fight in several costly stalemate battles along a series of hills running west to east just north of the 38th parallel were several small but intense and bloody battles took place.

The Battle of Pork Chop Hill, so Named for the Hill’s Topographical Appearance

One of the better-known battles fought at this time was the Battle of Pork Chop Hill, so named for the hill’s topographical appearance. Pork Chop Hill, or Hill 255, was a 300-meter high exposed hill outpost in front of the main line of resistance and was rather insignificant in terms of military or tactical importance. However, U.S. media attention to the event gave it great propaganda value since it was an ongoing struggle that lasted longer than any other single battle going on at the time.

The Battle of Pork Chop Hill Was Two Skirmishes During of 1953

The Battle of Pork Chop Hill was actually two skirmishes during the spring and summer of 1953. The first skirmish (Apr. 16-18) was victorious for the UN when the Communists broke contact and retreated after two days of battle.

In the second skirmish, beginning on July 6 and ending on July 10, both sides committed many more troops and the conflict lasted for five days. On the morning of July 11, the commander of the U.S. I Corps decided to abandon Pork Chop Hill to the Chinese and the 7th Infantry Division withdrew under fire.

UN forces first occupied Pork Chop Hill in October 1951 when the U.S. 8th Cavalry Regiment took over the hill. The hill was again occupied in May 1952 by Company I of the U.S. 180th Infantry Regiment. By November 1952, Pork Chop Hill was occupied and defended by the 21st Thai Battalion of the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division, which successfully repulsed an attack by the Chinese People’s Volunteers. Beginning on December 29, 1952, the outpost became part of the U.S. 7th Infantry Division’s defensive sector. Pork Chop Hill, itself, was one of several exposed hill outposts was defended by a single company or platoon positioned in sand-bagged bunkers connected with trenches.

Opposing the 7th Infantry Division were two divisions of the Chinese Communist Forces: the 141st Division of the 47th Army, and the 67th Division of the 23rd Army. These were veterans, well-trained units, an expert in night infantry assaults, patrolling, ambushes, and mountain warfare. Both armies were part of the 13th Field Army.

In a surprise night attack on March 23, 1953, a battalion of the Chinese 423rd regiment 141st Division attacked a hilltop outpost known as “Old Baldy” not far from Pork Chop Hill. Defending the hill was B Company from the 31st Regiment’s Colombian Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Alberto Ruiz Novoa. To relive the beleaguered defenders, the regimental commander, Col. William B. Kern, ordered C Company of the Colombian Battalion to relieve overwhelmed B Company, despite the Colombian commander’s protest. The movement began at 3:00 PM under heavy fire, making it difficult for C Company to advance toward their new position. B Company had been under constant artillery fire since their arrival and were eager to rotate.

Exposed Pork Chop Hill to a Three-Sided Attack

During the relief process, the enemy caught both companies exposed, enabling them to seize many of the defensive positions. For two days of stiff resistance, the badly beaten B and C Companies failed in retaking the hill since the 31st Regiment Command failed to send reinforcements. Rather than suffer more losses, the UN Command ordered “Old Baldy†abandonment. This preliminary fight exposed Pork Chop to a three-sided attack, and, for the next three weeks, Chinese patrols probed it nightly.

On the night of April 16, 1953, Company E, 31st Infantry commanded by 1st Lt. Thomas V. Harrold manned Pork Chop Hill. Shortly before midnight, an artillery barrage foreshadowed a sudden infantry assault by a battalion of the Chinese 201st regiment; Pork Chop Hill was quickly overrun, although pockets of U.S. soldiers defended isolated bunkers. A counterattack to retake the hill was ordered by Maj. Gen. Arthur Trudeau, command general of the 7th Infantry Division.

The two rifle companies selected for the counterattack were Company’s K and L, 31st Infantry. The tactical commander of the assault was 1st Lt. Joseph G. Clemons, Jr., company commander of K Company. L Company’s commander was 1st Lt. Forrest J. Crittendon. At 04:30 AM on April 17, the two rifles companies began systematically maneuvering up the hillsides under the cover of a heavy preparatory artillery barrage on enemy positions.

By Dawn Pork Chop Hill Belonged to the UN Forces

Although the Chinese defenders fought hard with everything they had, Company K and half of Company L (the other half had not been able to leave the trenches of an adjacent outpost) pushed forward to the top of the hill and into the main enemy trenches, often engaging in hand-to-hand combat. By dawn Pork Chop Hill belonged to the UN forces which had suffered almost 50 percent casualties. Concerned he did not have enough men to hold the hill should the Chinese return, Clemons called back for reinforcement. Since 2nd Battalion 17th Infantry was already attached to the 31st Infantry, G Company, commanded by 1st Lt. Walter B. Russell – Clemons’s brother-in-law – was immediately sent forward, linking up with Company K at 08:30 AM. All three companies were subjected to almost continuous shelling by Chinese forces (CCF) artillery as they cleared bunkers and dug in again.

Through a series of miscommunications between command echelons, Division headquarters ordered Russell’s company to withdraw at 3:00 PM after they too had suffered heavy losses, and did not realize the extent of casualties among the other two companies. By the time the situation was clarified, the companies of the 31st Infantry were down to a combined 25 survivors. Maj. Gen. Arthur Trudeau, by then on the scene, authorized Col. Kern to send in a fresh company to relieve all elements on Hill 255 and placed him in tactical command with both the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 17th Infantry attached and at his direction.

Kern sent forward Capt. Monroe D. King’s Company F, 17th Infantry which started up the hill at 9:30 PM under heavy artillery fire but reached the trenches at 10 PM suffering 19 killed in the process. At 11 PM, Col. Kern then ordered 1st Lt. Gorman C. Smith’s E Company, 17th infantry, to move up to reinforce F Company. To avoid the bulk of the artillery fire, Smith moved his rifle company around the right flank of the hill and up the side facing the Chinese positions.

Clemons’ Company K, had incurred 125 casualties, including 18 killed, of its original 135 men. After twenty hours of steady combat, the remaining seven members started off the hill singly just after midnight of April 17-18 and withdrew without further losses.

During the early morning of April 18, the Chinese 201st Regiment renewed its attack at 1:30 AM and again inflicted heavy losses on the defenders, nearly overrunning F Company. The timely counterattack by Lt. Smith’s E Company caught the Chinese by surprise on their flank and ended the organized assault. The Chinese 141st Division renewed attacks in company strength at 03:20 and 04:20 but did not gain further ground.

At dawn on April 18, an additional U.S. rifle company (A Company, 17th Infantry) climbed the hill to reinforce the 2nd battalion companies. Together the three companies spent the bulk of the day clearing the trenches and bunkers of all hiding Chinese and securing the hilltop. The battle ended that afternoon.

UN artillery had fired over 77,000 rounds in support of the three outposts attacked, including nearly 40,000 on Pork Chop Hill alone on April 18; the Chinese expended a similar amount.

Both the Chinese and U.S. infantry assaulted the hill initially under cover of a moonless night. Each used a heavy preparatory artillery barrage to force the defenders to take cover in bunkers and to screen the approach of the attacking troops. Chinese forces used rapid movement and infiltration tactics to close quickly on the trenches and surprise the defenders, while the US forces used small arms fire placed approximately 1 – 2 feet above the ground surface to limit defensive small arms fire, then maneuvered systematically up the hillsides under shellfire. Neither side employed supporting fire from tanks or armored personnel carriers (APC) to protect attacking troops.

Once inside the trench line, troops of both forces were forced to eliminate bunkers individually, using hand grenades, explosive charges, and occasionally flame throwers, resulting in heavy casualties to the attackers. For the UN forces, the infiltration of cleared bunkers by bypassed Chinese was a problem throughout the battle and hand-to-hand combat was a frequent occurrence.

Evacuation of casualties was made hazardous by almost continuous artillery fires from both sides. The 7th Infantry Division made extensive use of tracked M-39 APCs to evacuate casualties and to protect troops involved in the resupply of water, rations, and ammunition, losing one during the battle. In addition, the UN forces employed on-call, pre-registered defensive fires called “flash fire” to defend its outposts, in which artillery laid down an almost continuous box barrage in a horseshoe-shaped pattern around the outpost to cover all approaches from the Chinese side of the main line of resistance.

The Chinese Again Attacked Pork Chop

The 7th Infantry Division rebuilt its defenses on Pork Chop Hill in May and June 1953, during a lull in major combat. Final agreements for an armistice were being hammered out and the UN continued its defensive posture all along the MLR, anticipating a cease-fire in place.

On the night of July 6, in the second skirmish, using tactics identical to those in the April assault, the Chinese again attacked Pork Chop. The hill was now held by Company A, 17th Infantry, under the temporary command of 1st Lt. Alton Jr. McElfresh, its executive officer. B Company of the same regiment, in ready reserve behind the adjacent Hill 200, was immediately ordered to assist, but within an hour, A Company reported hand-to-hand combat in the trenches. A major battle was brewing and division headquarters ordered a third company to move up. The battle was fought in a persistent monsoon rain for the first three days, making both resupply and evacuation of casualties difficult. The battle is notable for its extensive use of armored personnel carriers in both these missions.

On the second night, the Chinese made a new push to take the hill, forcing the 7th Division to again reinforce. Parts of four companies defended Pork Chop under a storm of artillery fire from both sides. At the dawn of July 8, the rain temporarily ended and the initial defenders were withdrawn. A fresh battalion, the 2nd Battalion of the 17th, counter-attacked and re-took the hill, setting up a night defensive perimeter.

The Commander of the U.S. I Corps Decided to Abandon Pork Chop Hill to the Chinese

On both July 9 and July 10, the two sides attacked and counter-attacked. A large part of both Chinese divisions was committed to the battle, and ultimately five battalions of the 17th and 32nd Infantry Regiments were engaged, making nine counter-attacks over four days. On the morning of July 11, the commander of the U.S. I Corps decided to abandon Pork Chop Hill to the Chinese and the 7th Infantry Division withdrew under fire.

Four of the thirteen U.S. company commanders were killed. Total U.S. casualties were 243 killed, 916 wounded, and nine captured. 163 of the dead were never recovered. Of the Republic of Korea troops (“KATUSA”) attached to the 7th, approximately 15 were killed and 120 wounded. Chinese casualties were estimated at 1,500 dead and 4,000 wounded.

Less than three weeks after the Battle of Pork Chop Hill, the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed by the United Nations Command (Korea), Chinese Peoples’ Liberation Army, and North Korean Peoples’ Army, ending the hostilities.

In 1959 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios released the film ‘Pork Chop Hill’ starring Gregory Peck as 1st Lt. Joseph G. Clemons, Jr, Rip Torn as Lt. Walter Russel, and George Peppard as Cpl. Chuck Fedderson. The film is based upon the book by U.S. military historian Brig. Gen. S. L. A. Marshall.

Below is a short piece featuring Peck talking about A.L. Marshall’s book as well as clips from the movie.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XPaEECzwUxI

I was just a kid in school at the time of the Korean War. However, I remember hearing about the successes and failures reported on a daily basis in both the newspapers and radio. The one thing that those reports confirmed for me was a strong desire to serve my country in some way not connected to the infantry. Years later, when I got my draft notice and my call to go get my pre-induction physical I knew it was time to find an alternative. As a Southern California native, my first choice was to join the US Navy. After boot camp in 1962, I was assigned to the USS St. Paul and placed in the engineering spaces as a boiler tender. Spending time in the boiler room resulted in frequent head-to-toe soot from keeping things operational. My promotion to the “Oil Gang” ended the soot episodes. The bright spot of my time aboard was when the movie “In Harms Way” was being filmed. The USS St. Paul was the heavy cruiser that John Wayne commanded. While I never got to meet him or even see him during the filming, I did see Burgess Meredith frequently along with Otto Preminger who was the director. Another bright spot was the improvement in the chow being served while the film crew was aboard.

I have an uncle who was an army corpsman. He was involved with that last battle during the abandonment of the hill. He kept going in to pull off wounded soldiers even when he was told to evacuate himself. He was awarded a silver cross for this. At his request, I’m not including his name. He has never talked about his experiences in Korea to this day, and is still with us, at age 90. For a long time after coming home, one could see the strain and even fear on his face.

Hello,

My name is Deborah Anderson I am writing to you on behalf of my friend Julie Nelson. We believe her uncle Pfc Thomas Edward Nelson from La Point Wisconsin may have served with your uncle. Nelson was C Company, 1st Battalion, 17th Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division. He died in the last battle on Pork Chop Hill. Was your uncle in this unit and if so would you be willing to ask your uncle if he new Thomas E. Nelson? Thank you in advance for any information you may have.

My father was there also at last battle up until lately he began to talk about the Korean War. When he meets another veteran he would also open up or should I say they would open a conversation with him and amazed to see a Korean vet. He would mention about a friend of his he says he talk to him one morning at the hill never seen him again. He would say waste of men for that hill and very bless to come home without losing any limbs. Like one of his school friends who lose a leg. As your uncle I seen the same strain in my father face .

He is now 91 and I am very grateful. April 29, 2023 at 16:00

I am in contact of Mr. Tommy Poss who can recall events from his experience at Pork Chop Hill. I would love to connect him with this company A, 17th infantry division.

As mentioned above, I was with Fox company, 2nd Bat, 8th cav in Oct 1951, (I am 91 ) . Our position on the MLR was about a mile or so from PC hill(220 or 250) and the outpost looks like a pork chop on the map. It would be interesting if someone would write an article about The 3rd platoon, fox co’s fight on that hill on thanksgiving eve , November 1951. The third plt/LDR also was awarded the CMH for that fight.

I have an uncle who was one of the few to walk off that hill. Even at 90 now he has never spoken about it, I guess he never will. What was done or not done by men in the midst of battle can be viewed with an unfair lens when looked on from a distance in the safety of ones home. Some vets carry a load of guilt that I fear they really don’t need to. Every soldier returns from the battlefield a casualty of war. Even if the body is whole, the soul never will be. So now it is up to us to share our love and support for them even if they shrug away from it or feel unworthy of it. You were soldiers once, there in that place. That says it all. Nothing more need to asked or given. You have the right to be and nothing less.

love the story of the battle pork chop hill !!!!!!!!

i cant get out could u possible send me a printed copy of the battle of pork chop hill.

thank you so very much.

ron davidson

9790 – 66th.st.north lot # 149

pinellas park florida 33782