During the last few years of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union – both long weary of the other – became unlikely allies against Adolf Hitler’s takeover of Eastern Europe. Following the defeat of German in 1945, however, the wartime allies became mortal enemies, locked in a global struggle to prevail militarily, ideologically, and politically in a new “Cold War.” To learn of the other side’s military and technical capabilities, their actions and intentions, both sides used spies to gather information and intelligence about their enemy.

Alarmed over rapid developments in military technology by his Communist rivals, President Dwight D. Eisenhower approved a plan to gather information about Soviet capabilities and intentions using reconnaissance aircraft. Thus became the birth of the U-2 spy planes.

Beginning in 1956, U-2 spy planes were making reconnaissance flights over the Soviet Union, giving the U.S. its first detailed look at Soviet military facilities. Managed first by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and later the U.S. Air Force, the U-2 provided day and night, very high-altitude (70,000), all-weather intelligence gathering. It was relatively slow, however.

The aircraft’s vulnerability and the need for a faster reconnaissance aircraft were underscored following the downing of two U-2s. The first in 1960 when Francis Gary Powers’s U-2 was shot down over the Soviet Union and the 1962 fatal downing of Air Force Major Rudolf Anderson’s U-2 after being hit with a Soviet missile while flying over Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crises.

The SR-71 Was Built by Lockheed’s Skunk Works Team

Looking to replace the U-2, the CIA turned to Kelly Johnson, one of the preeminent aircraft designers of the twentieth century, and his Lockheed’s Skunk Works team. Together they had a track record of delivering “impossible” technologies on incredibly short, strategically critical deadlines. The design the team came up with became the SR-71, which became the precursor to “stealth” aircraft that followed.

A total of 32 aircraft were built; 12 were lost in accidents, but none lost to enemy action. Since 1976, with speed exceeding 2,000 mph, it has held the world record for the fastest air-breathing manned aircraft.

Finished aircraft were painted a dark blue, almost black, to increase the emission of internal heat and to act as camouflage against the night sky. The dark color led to the aircraft’s call sign “Blackbird.”

The SR-71 Blackbird Operated at High Speeds of Over Mach 3

During reconnaissance missions, the SR-71 operated at high speeds of over Mach 3 with a flight crew of two in tandem cockpits, with the pilot in the forward cockpit and a Reconnaissance Systems Officer (RSO) monitoring the surveillance systems and equipment from the rear cockpit.

If a surface-to-air missile launch was detected, the standard evasive action was simply to accelerate and outfly the missile. Since it was much faster than the Soviet’s principal interceptor, the MiG-25, that same evasive technique was used.From the beginning of the Blackbird’s reconnaissance missions over enemy territory (North Vietnam, Laos, etc.) in 1968, the SR-71s averaged approximately one sortie a week for nearly two years. By 1970, the SR-71s were averaging two sorties per week, and by 1972, they were flying nearly one sortie every day. Two SR-71s were lost during these missions, one in 1970 and the second aircraft in 1972, both due to mechanical malfunctions.

At the cost of $85,000 per hour to operate each SR-71 Blackbird and $260 million per year to support some in Congress were critical of its high costs. By the mid-1970s, faced with budget cuts and concerns, the program was placed under close scrutiny.

A strong opponent of the costly program was Dick Cheney, President Gerald Ford’s Deputy White House Chief of Staff. To push his agenda, he went before the U.S. Senate Appropriations Committee and presented a thorough, carefully detailed study on the high costs of the SR-71 program.

That presentation won over many undecided members of Congress, and soon the cry grew to suspend its use. The nail in the program’s coffin was the revelation that parts were no longer being manufactured, and other airframes had to be cannibalized to keep the fleet airworthy. Eventually, the program was scuttled partially because there was a general misunderstanding of the nature of aerial reconnaissance and a lack of knowledge about the SR-71 in particular (due to its secretive development and usage) was used by detractors to discredit the aircraft, with the assurance given that a replacement was under development.

The Decision to Retire the SR-71 from Active Duty

The decision to retire the SR-71 Blackbird from active duty came in 1989, with the last missions flown in October that year. Four months after the plane’s retirement, General Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr., was told that the expedited reconnaissance, which the SR-71 could have provided, was unavailable during Operation Desert Storm. America’s sole air reconnaissance aircraft once became the U-2.

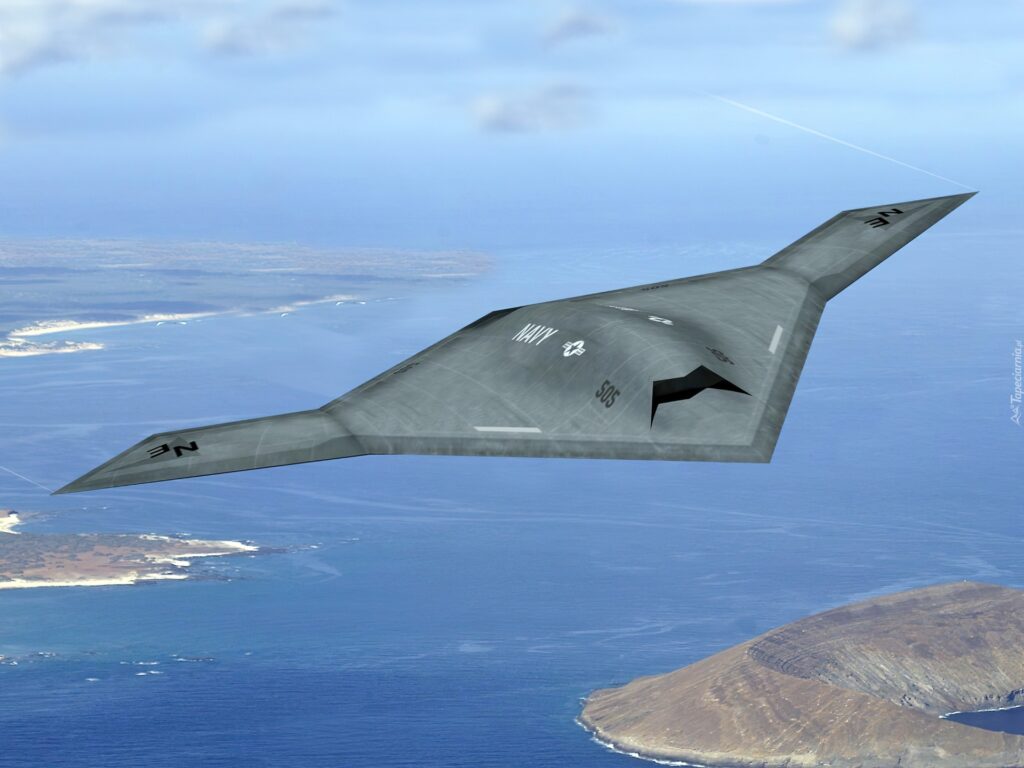

In November 2013, media outlets reported that Skunk Works has been working on an unmanned reconnaissance airplane; it has named SR-72, which would fly twice as fast at Mach 6. However, the Air Force is officially pursuing the Northrop Grumman RQ-180 UAV to take up the SR-71’s strategic ISR role.

When it comes to curb appeal, few airplanes in history can match the look of the SR-71 Blackbird. And nothing in the Air Force’s inventory – past or present – can beat its signature performance characteristics.

While in the Air Force I was sent to Brake AFB to do upper atmosphere work as the SR-71 was being evaluated and pilots were trained.