For 19-year-old Pat Finn, a Minnesota Marine with Item Co, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, the night seemed colder and darker than any of the others he’d experienced since landing in Korea. His Battalion had just arrived at a desolate, frozen lake he would remember for the rest of his life: the Chosin Reservoir.

Chosin Reservoir Hit by a Devastating Surprise Attack

As the sun went down on November 27, 1950, and temperatures sank to 20 degrees below zero, Marines at Yudam-ni, a small village on the west side of the Chosin Reservoir, hunkered down for what they hoped would be a quiet, uneventful night.

“The war was all but over,” Finn recalled in his diary written weeks later from a hospital bed in Japan. “You’ll be home by Christmas,” he’d been told.

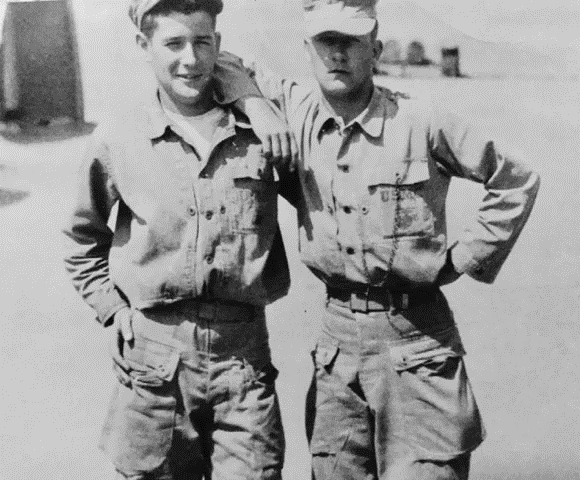

But his buddy, Eddie Reilly, wasn’t buying it. In his usual pessimistic tone, he told Finn, “Pat, I don’t like the look of all this, it sounds too good.” For the next four hours, the two Marines scraped and dug into the frozen, rocky ground, Reilly constantly reminding his friend that if something went wrong, a fighting hole would save them from flying bullets and shrapnel.

“I hate this place,” Reilly said for what seemed like the hundredth time, “but we’re not going to get caught with our pants down, keep digging!”

When the hole was finally finished, Finn and Reilly, both exhausted, squeezed into what they believed would be a safe haven for the night. Minutes later, their lieutenant yelled, “Saddle up!” Their platoon was heading to higher ground.

Chosin Reservoir Erupts in Nighttime Chaos

Nothing, not even a foxhole, would save them from the horror that unfolded over the next eight hours. Finn, Reilly, and hundreds of their fellow Marines were attacked by thousands of Chinese. In the first onslaught of a major Communist offensive that would alter the course of the war, Chinese soldiers, under direct orders from Mao, had launched a vicious attack to annihilate the 1st Marine Division. Wave after wave of Chinese descended on the Marines.

Overwhelmed and outmanned, Finn and his buddies were overrun by the Chinese. With enemy soldiers breaking through their defenses, close-in fighting, sometimes hand-to-hand, erupted. “They were mixed in right with us,” Finn remembers. Hundreds of white-clad Chinese, oozing a pungent garlic smell, swarmed over Finn and Reilly’s position.

“About that time, Pat Garvin from Detroit threw an illumination round,” Finn recalled. The Chinese “with their white jackets looked like ducks in a shooting gallery.” Silhouetted against the lit sky, they were mowed down by machine-gun fire, but as soon as they fell, men running behind them grabbed their fallen comrades’ weapons and charged ahead. “They just kept coming,” Finn remembers.

In the chaos of the attack, the young Marine ran straight into a Chinese soldier. “I went to shoot him and ‘click,’ my rifle was frozen.” Stunned and realizing he was about to get hit, Finn yelled, “He got me!” A Marine heard Finn scream and fired a round at the Chinese fighter. The soldier died instantly.

When the sun came up the next morning, an estimated 300 frozen, grotesquely twisted Chinese corpses littered the snowy North Korean hillside. Famed Korean War historian Roy Appleman, in his seminal work on Chosin, Escaping The Trap, wrote, “Silence prevailed on the hill.”

Chosin Reservoir Claims Lives as Marines Fight to Survive

In a bloody, 24-hour period, the Korean War had changed. General Douglas MacArthur, the supreme commander of UN Forces in Korea, was shocked. He had previously told President Truman and the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the Chinese would not enter the war. They wouldn’t dare, he had boasted.

With “135 American dead, 725 wounded, and 60 missing” in just one day and thousands more dying over the next month, the American public was also stunned.

Finn and his buddies would eventually fight their way 14 miles to Hagaru-Ri, where they would link up with remaining American units in the area and then “attack in another direction” to the port of Hungnam nearly seventy miles away.

On the first night of the breakout from Yudam-ni, the Chinese attacked again. When the fighting ended the next morning on Hill 1520, only 20 Marines out of a company of nearly 250 were still standing. The rest were dead, wounded, or missing. Finn was amongst the survivors.

He had lived through one of the most terrifying nights at Chosin. In a brief lull in the fighting that night, he had tried to save a group of Marines hit by mortar fire. “They were all close to death,” he remembered. “One was still conscious. He asked me to give him a cigarette and cover his legs because they felt frozen. He didn’t have enough legs to cover.” There was nothing Finn could do. The man died minutes later.

Before daybreak, another mortar attack took place. A round landed “about four feet” from Finn’s foxhole. “I was protected from all the shrapnel,” he told his father, “but the blast threw me right out of the hole.” The Marines behind him, already mortally wounded, lying on the ground and begging for help, were all killed. “It was good in a way; it put the four boys behind me out of their misery. They were really in misery, believe me,” he wrote.

“All of my buddies were killed,” Finn continued in a letter to his father dated December 10, 1950. “Remember me telling you about Eddie Reilly? He was killed. That really hurt. He treated me like a big brother. All night long, he would keep coming out of his foxhole to see that I wasn’t wounded or anything.” That was the last time he saw his friend. PFC Edmund H. Reilly was listed as “Killed In Action” on December 2, 1950.

He also lost his buddy, Jerry “Peanuts” Caldwell, a 17-year-old high-school football standout. “He was a great guy. He would stay in the barracks writing and reading the Bible while we were at the slop shoot,” Finn recalled. Another good friend, David Flood, went missing, and three days later, a Chinese soldier was killed wearing the Marine’s jacket. “It was one of the eeriest feelings I had during the entire war,” Finn explained. “Knowing my buddy had died, and his body had been stripped of its clothes was hard to take.”

Chosin Reservoir Leaves a Lasting Mark on a Survivor

By December 9, Finn was in Japan. He had made it down the MSR and had been evacuated by air to a US military hospital where he was being treated for severe frostbite. In typical Marine bravado, he said, “You and mother will never know how close you came to collecting that $10,000 I used to joke about.”

Looking back on his Chosin odyssey, Finn realizes the epic ten-day breakout to the coast was a defining moment of the Korean War and his life.

After recovering in Japan and returning to the US, Finn married started his career and had five sons. He worked for the same company for 48 years and retired as its CEO in 2000. After a divorce from his first wife, he remarried. His second wife, Arlene, was with him when we met in Seoul last month. During my interview with the couple, I asked Pat how he coped with what he’d been through at Chosin. “I drank,” he answered matter-of-factly.

“For so long,” he told me, “I tried to put the war out of my mind, lock it away, or erase it. But it was always there.” His life eventually changed, and he has been sober now for 45 years.

As I talked with his wife, it was obvious how empathetic she is towards her husband and how knowledgeable she is of what happened to him during his time in Korea. She’s a psychologist, and her understanding of what he experienced at Chosin and how to deal with it shines through in her words and actions. “For so many years,” she explained, “he coped by avoiding memories, thoughts, and feelings related to his war experience.”

Thankfully, Pat can now talk about the war with his family and friends, go to Chosin Few reunions, and even allow complete strangers who sit next to him during a bus tour to interview him. “He can actually enjoy the present,” Arlene said enthusiastically.

Pat and Arlene, thank you for your friendship and for sharing this remarkable story of sacrifice and survival. Mr. Finn, I salute you, your Marine buddies who never came home, and all the servicemen who fought in the Korean War.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the Chosin Reservoir, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

My father Arthur Wedemeyer

Was a member of George Company third battalion fifth Marine’s in 1950, before the Korean War broke out, he went home on leave. When he returned to Camp Pendleton. He was sent to Korea and was assigned to L 4 11 as part of a local security for the one 105 canyons. My father was wounded three times at the reservoir twice on December 2, 1950. Were you late in the snow for three days before his fellow Marines found him.

My Uncle, Myrl Boys, was a 1st Lt. & Platoon Leader in I-3-5, 1st Marine Division, at the Battle Of Chosin Reservoir. He was wounded in action on the night of December 2, 1950. I would be interested to know if Mr. Finn would have any memories of my uncle. I have photos of him and a copy of his service record.

Coming to Terms With Being a Marine Who Never Went to War

Being a United States Marine and a riflemen first I served with great honor for six active years 1953-1959 and two years after that in the MC Inactive Reserves.

HELL YEAH, I served my time in the Marine Corps and proud of it! Shot many rounds of various weapons but never in anger! I was always ready to do my part. The Marine Corps found me more valuable flying helicopters and serving POTUS Eisenhower in 1958-1959!