PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

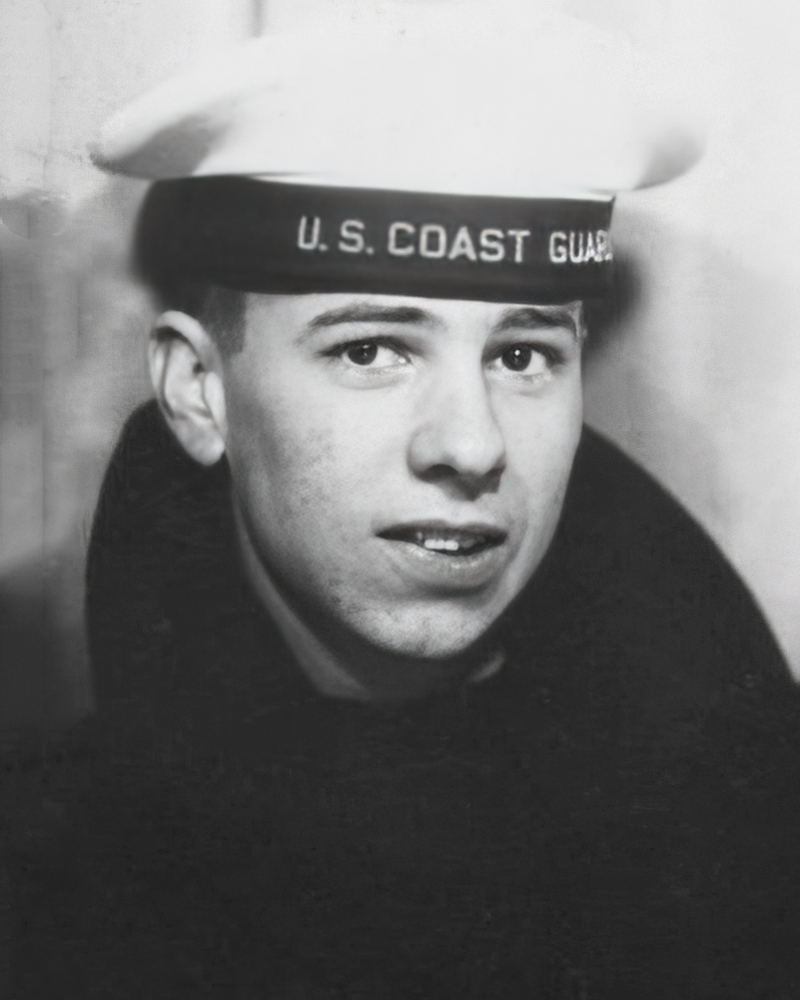

The following Reflections represents AT2 Larry French’s legacy of his military service from 1966 to 1970. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Coast Guard.

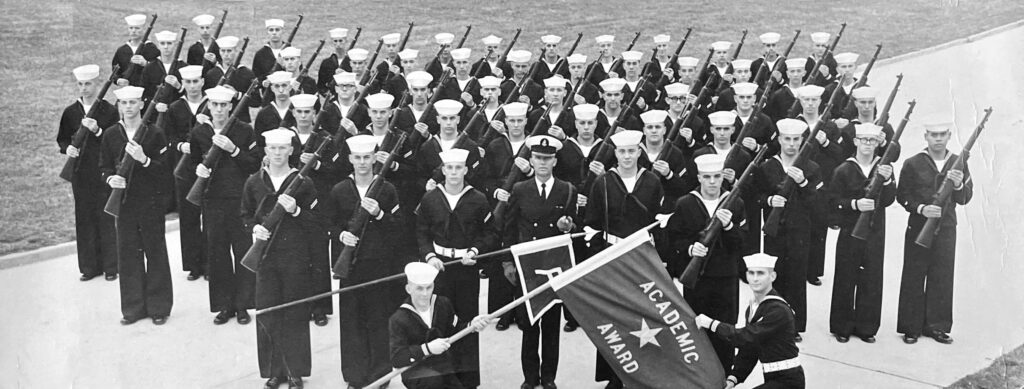

Being the class clown in high school didn’t adequately prepare me to be gainfully employed in the real world. The Vietnam War was ongoing, and everyone our age was getting drafted. A lot of the kids in our class of 1966 just went ahead and signed up for one of the branches. My dad told me to sign up for the Coast Guard and that I could learn a skill or a trade. (I think he might have been trying to direct me to a branch that had a lower likelihood of ending up in Vietnam. I had no idea what the Coast Guard was or its mission. I had graduated high school at 17 years old and looked like I was 15. So, right after graduating, I went to speak to the recruiter, and his first reaction was, “Well, son, you have to graduate from high school first.” And I told him I had just graduated, and then he said you have to have a parent sign for you. and I told him they were okay with that, and they did.

About halfway through the summer, I started getting worried about going into basic training. I went back for another chat with the recruiter and asked if there was anything I needed to do to prepare for boot camp. (I’m sure he must have thought, “I’ve got a live one here.”) In response to my question, he asked if I had ever been to summer camp. And I told him yes, I have; every year, my sister and I go to church camp for a week. And the recruiter quickly assured me, “You’re good to go”! That put my mind at ease … and then the real reality hit.

As our bus arrived at Cape May, we were greeted by a “welcoming” crew of training staff yelling, screaming, and swearing at us. I thought, “Wow, they’re talking about God but talking about him in a little different way than they did a church camp. And that was my starting gate into the CG.

I had a run-in with my Company Commander on my second day there. He came along and was carefully inspecting us, up close and personal. He got in my face and said, “Boy, did you shave this morning?” I replied, “Sir, no, sir. I don’t have to shave, sir!” His response was, ” You’re a man now, and you have to shave!” I almost said, “Well, no, actually, I don’t have to shave …” Fortunately, I had enough sense just to say, “Sir, yes, sir!” and shut up.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

After basic training, I was stationed in Portsmouth, VA, on a 180 ft. buoy tender, the CG Cutter Conifer. At that time, there was more protest against the military and the war. I remember a Portsmouth store that said, “Dogs and sailors not allowed.” Today, to see the respect that our men and women in the military are shown brings tears to my eyes. Many of us very young men (and some women) were there to serve our country and were treated very poorly by the public in general.

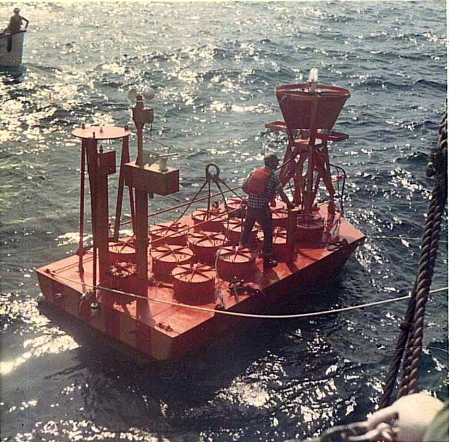

More recently, on a TV show (May 2018) on Mike Rowe’s World’s Most Dirtiest Jobs, his “show & tell” was on a CG buoy tender. My wife turned to me and said, “Did you do that?” Any of you who served on one of these “boats” knows what a challenge this kind of work was like. We were responsible for the navigational guides from Cape Hatteras to Ocean City, MD. We also replaced the ice buoys up and down the Potomac River. In the winter, the decks were icy and slick, and in the hot summer weather, our work, cleaning and repairing buoys, scraping barnacles, stunk so bad it would make you want to bark. We didn’t always pull them completely out of the water. Sometimes, we would pull alongside the buoy bobbing up and down. Then one of us (usually a seaman) would jump on the cage of the buoy and do a test of the batteries and replace the light bulbs that were dead. As a young person, jumping buoys was a blast, and we were oblivious to the potential dangers.

In those days, there was a lot of protest music on the radio stations. So many memories are linked to those songs. Listening to oldies of the ’60s brings back a mixture of emotions. There were a lot of fun songs, too; I remember hearing the Beatles sing “We All Live in a Yellow Submarine,” and somehow, we related it to a CG buoy tender. This sure wasn’t my dream job & the sleeping quarters were called the “snake pit.” I hoped to go to electronic school, and here I was, scraping barnacles, not exactly the career prep for which I was hoping. So, I continued to request to go to electronics school. Amazingly, my request was granted after six months, and I transferred to CG Training Center at Groton, CT.

When I got to Groton, they were in the initial phases of moving the training center from Groton to Governor’s Island, NY (this was right off of Manhattan and required riding a CG Ferry back and forth). I was in a group of about ten fellows who volunteered to come to Governor’s Island early and work on getting the barracks and grounds prepared for the rest of the training center to transfer to New York. That was a great duty station before the schools officially arrived.

Being from the deep South (Alabama and North Carolina), my southern accent got a lot of unwanted attention. It seemed like every time I opened my mouth, people were laughing their heads off and saying, “Say that again.” I gradually began to lose any traces of my southern drawl. But talk about culture shock! Here I am, 18 and really naive, and not knowing anything about a big city. There would be men sitting beside me on the subway and starting what I thought was a friendly conversation – but quickly, I learned this wasn’t quite the same as Southern hospitality if you get my drift.

Another funny story happened around Christmas. Everyone knows how New York is so beautifully decorated – especially Rockefeller Center. Most of the fellows in my class were from the northern areas, Maine, New Hampshire, Minnesota, Vermont, etc. Someone had the great idea that we should go ice skating and they invited me. I declined, saying that I had never learned how to ice skate growing up in the South. The rest of the guys quickly chimed in that they didn’t know how to ice skate either, and we could all go and have some fun trying to skate. So, I agreed to go. After getting the skates laced up, one of the guys said, “Here, let me give you a hand,” and grabbing my hand, he started flying across the ice, pulling me along with him. And to end my personal ice-skating lesson in the middle of Rockefeller Center, he slung me, launching me through a crowd and across the ice. Welcome to New York! This left a clearly indelible memory about my time at Rockefeller Center and my first skating experience.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

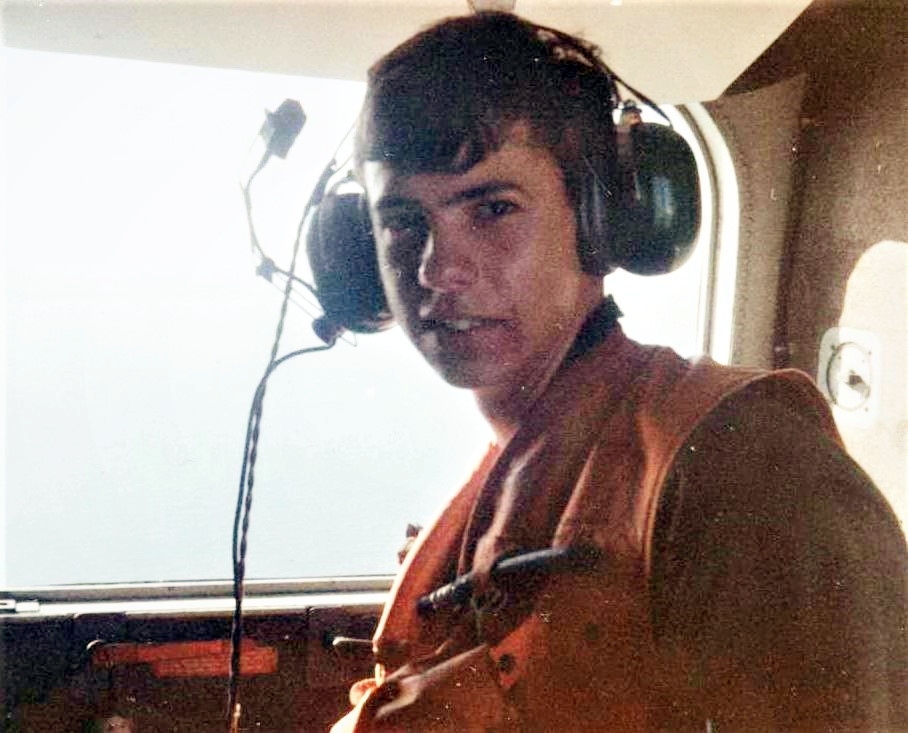

Being involved with the Search and Rescue flight out of Miami was the most impactful experience. We had a lot of different missions. Little known was the reconnaissance flights off of Cape Canaveral, Florida. In the early 70s, whenever there was a rocket launch, we would fly our HU-16s over the “trawlers” that patrolled up and down the Florida coastline. Interestingly, we had a Navy photographer assigned to our flight with his 35 mm camera. He was strapped in the back hatch of the plane with a harness. The pilots would make slow and low, sweeping runs over the trawlers (most of them Russian). This would allow the photographer to hang out the hatch and take many photos. These ships were equipped with huge domes on the decks – hiding their radar and other electronic detection equipment. Our job was to record all the vital information: the direction they were traveling, their speed, the size of the ship, country of origin, and other significant marketing or details.

Another regular mission was daily flight (8- and 10-hours) searches to patrol the waters and islands between Key West and Cuba. One of the most meaningful parts of this mission was looking for Cuban refugees. It was not uncommon to find Cubans attempting to flee Cuba on almost anything that would float. Also, we would find people stranded on these little barren and isolated islands. Our job was to notify Air Station Miami that we had located refugees. We would have to encrypt our messages to include the location, the number of people, and other vital info. If we did not encrypt the information, a Cuban cutter would come out and apprehend them.

The mainstay of our flights was ships and boats and people in distress. We would generally fly eight or more hours in a search grid pattern in an effort to locate something generally pretty small in a vast body of water. We would rotate shifts, taking “lookout” from the back hatches of the planes. The HU16s were designed to land and take off from water, but this could be very risky in the open ocean. If the winds picked up and the seas got choppy, that would make it tough to get up to airspeed, and then you were in a lot of trouble; so rarely did we land in the open seas.

The plane carried a gas-powered sump pump in a sealed container (about the size of half of a fifty-gallon drum). Once we located the vessel in distress, we would assess the situation and make preparations to drop the pump. The canister had a long, bright orange ski rope attached. The goal was to drop the pump safely and, in a way, to ensure the rope went across the boat. Unfortunately, it didn’t always go completely as planned. You can imagine the surprise when the pump landed just a little too close!

Larry French (Copyright 2022)

Did you encounter any situation during your military service when you believed there was a possibility you might not survive? If so, please describe what happened and what was the outcome.

We were flying in a HU16 Grumman Albatross, returning from a big search around the island of Grand Turk. As some of the crew members would do, they would stash away some cheap, duty-free rum from the islands. (Initially, one of the main purposes of the Coast Guard was to stop rum running from the islands to the US. There is some real humor in the irony of this.) On a long flight, a little rum in the coffee made the trip a little more pleasant. (At least that’s what they told me.)

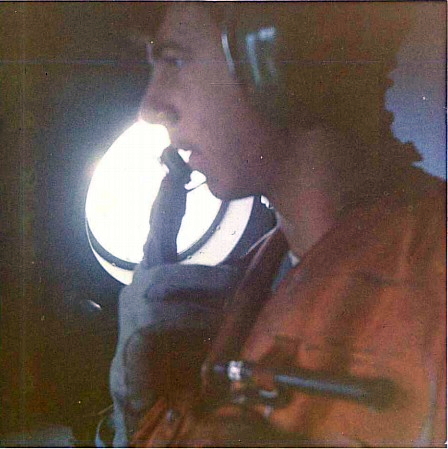

I was the radioman on this flight and the third man in the cockpit, seated right behind the co-pilot. These planes were noisy, and we were to always wear earplugs and headsets for hearing protection and to communicate with the plane’s intercom system. To the right of the radioman’s seat was a “porthole” shaped window that looked out at the starboard wing, the roaring engine, and the propeller. (For those that don’t know, the Albatross is a two-engine plane that can take off and land on water.) About halfway out on the lower side of the wing, there was a “drop tank” that was used to carry additional fuel for longer flights. Near the end of each wing was a “float tank” that extended down and was used to help support and stabilize the aircraft when it did water landings.

When it comes to facing a large, severe, turbulent storm, we generally dodge them if at all possible. We fly around them. We’ll fly over them. We’ll pass under them, but you do not want to fly through them. (These planes are not pressurized, so generally, the pilots would stay under ten thousand feet). This was an unusually large storm, and we could not find a way around it, so our only choice was to fly through it. As I would observe the altimeter, we would be flying at seven thousand feet, and almost instantly, we would drop two or three hundred feet. It was as if there were vacuums in the sky where there was no air to give the plane a lift. What a roller-coaster ride!

After strapping down in my seat, I began to gaze out the “porthole” window, watching as the wing would fade in and out of sight because of the thickness of the clouds. Now, we were really in the “soup” with extremely limited visibility. Even with the use of the radar, we had difficulty detecting a path out of this monster storm.

I guess it was a design flaw with these planes; the overhead escape hatch doors were not completely watertight, and we had a number of leaks with water coming into the cockpit. This was bad news for a couple of reasons. Most of the avionics (transmitters and receivers) are secured in this area, and they do not respond well to being wet. Additionally, it added to the discomfort for the crew members, and it also increased the weight of the plane and made handling it even more difficult. In the meantime, some of the crew members were enjoying their stash of rum in their coffee; some a little too much (if you know what I mean). The flight mechanic was a seasoned ole-timer with a lot of experience. He would regularly watch the engine analyzer for any irregularities with either engine. Over the last hour, he had reported that there was a potentially serious problem with the starboard engine. He was generally a pretty laid-back guy, but now he looked agitated. We weren’t sure if we had a problem with the engine or with a mechanic who had a little too much rum and coffee.

As the radioman, one of my jobs was every fifteen minutes to radio our home base, “Miami Air Station,” and report “operations normal.” Then Miami Air Station would calmly reply, “Coast Guard Seven-two-two-three, Roger, your fight operations are normal.” Somehow, hearing those words brought a little solace; “somebody out there is watching out for us.”

Flying blind through these thick clouds being bounced all over the place, experiencing dripping water, a veteran flight mechanic beginning to panic as he tells us we’ve got a problem with the right engine made this two-hour part of the flight seem like an eternity. And then, gradually, we saw the clouds begin to loosen up, the skies became brighter, and the rains stopped. Finally, we broke out into a beautiful velvet-blue sky. Below was the pale green of the Atlantic Ocean scattered with rainbow-colored coral reefs. There was a sense of relief; “we’re going to make it.” Unfortunately, it was a premature sigh of relief.

Before completing our sigh of relief, the right generator warning light lit up the instrument panel. I then contacted the base, “Miami Air, Miami Air, this is Coast Guard Seven-two-two-three. Be advised we have an indication that our right generator has failed. Our position is four zero miles southeast of Nassau. Over.” Miami answered, Coast Guard Seven-two-two-three, this is Miami Air, Roger.”

By the time I had completed my communications with Miami, the pilots had decided that because there were chunks of metal, oil, and amber sparks streaming from the cowling, they should “feather” (shut down) the right engine. I again contacted Miami Air and reported we had shut down one of our engines. Miami’s response was, “Are you requesting emergency flight status”? When I passed this question on to our pilot, he said, “Tell them hell no, we always fly like this!” He quickly stopped me and said, “No, no, don’t say that. Tell them our location and yes to the emergency flight status”.

The plane has an auxiliary power unit (APU) in the back of the plane to provide electricity for the plane when the engine generators are shut down. To reduce the stain on the left engine and augment the electricity supply, the crew in the rear of the plane started the APU. Then, to everyone’s surprise, an announcement came from the rear of the plane that the APU had just caught on fire and had to be secured immediately (shut down). The fire was quickly extinguished, and everything was back to? Well, it was not exactly normal, but we were still airborne.

The noise of the roaring engine was reduced by half, but what’s a little noise in a situation like this? These planes were designed to fly on two engines, and we were steadily losing altitude. It felt like Nassau was four hundred miles away. At last, we could see the island and the runway. I can’t remember when a landing strip has ever looked so good. Red flashing lights lined both sides of the runway, indicating that rescue equipment was there. But there was one more serious problem: how do you stop the plane?

These prop planes are slowed down by reversing the propellers on the engines. Now that one engine has been shut down, you can’t reverse just one side for obvious reasons. So, being unable to reverse the engines, the pilots were forced to use the aircraft’s brakes to the point that the brakes almost ignited. Black smoke billowed out from around the tires and the landing gears.

We were told, as soon as the plane stopped, to get out as quickly as possible and move away from the plane, and we did. We were all so grateful to have our feet on the ground once again, safe and sound.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

Everything had a significant impact on my life, from boot camp to being on a buoy tender in Portsmouth, VA, to Electronics & radioman’s school in Governor’s Island, NY, to Aviation Electronics in Elizabeth City, NC, and especially my two years at the Miami Air Station.

Of those, maybe the one I liked the least was being on a buoy tender. I grew up pretty sheltered, and my time on that 180-footer sure expanded my vocabulary. These guys were sober (for the most part), and they’d make the proverbial “drunk sailor” sound like a choir boy. I didn’t mind the work too much; however, chipping paint was no fun. At 18 years old, being told to jump on a bouncing buoy and do the needed maintenance was a lot of fun. (Somehow, the thought of being crushed to death if you got caught between the ship and the buoy just never crossed my mind.)

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect on to this day.

On the buoy tender, we worked on a weather buoy that was in three miles of deep water about 300 miles off the coast of NC. That was a big challenge to recover it when it quit working. The hardest part was recovering the three miles of rope it was anchored with.

The other memories are from Miami Air Station (see the story about “requesting emergency flight status”), under which we could have died question.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

My Air Crew wings. I really like the whole search and rescue flights. At that time, we flew the eight and 10-hour patrols daily to look for people on the islands between Key West, FL, and Cuba. (Most of the people were Cuban refugees who were stranded on these barren islands.)

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

The Air Crew wings as described.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

Mike Rawson. He was stationed with me in Miami, and he was instrumental in reminding me about how important it was to hold to your Christian values and live a life that was pleasing to God.

Can you recount a particular incident from your service which may or may not have been funny at the time but still makes you laugh?

As we were toward the end of basic training, there were two or three of us who had guard duty on a weekend, and the rest of our company had weekend days off. Our job was to “greet” everyone when they returned. Actually, we were to make their “welcome back” to be as miserable as possible. The regular Coasties that were actually stationed at Cape May and ran the front gate guard house would yell and scream at us to give everyone coming back to the base a really hard time when returning. We’d have to get up in their faces, scream at them, make them “give us 20 push-ups,” and really get on them.

So, when the guys in my company came to the gate, especially the recruits that had leadership in our company, we had to read them the riot act. As I’m doing this, I can see in their face, “Boy, are you going to get it when we get back to the barracks?” So, I’m yelling at the top of my lungs and belittling them as we were told to give them a hard time and thinking, “Oh my, I am going to get it later.”

So sure enough, when I returned to the barracks, about a half-dozen of the company leaders “invited” into the office for a little meeting. One guy reached over, grabbed my shirt, and lifted me off the floor, holding me up against the wall, and all of them were screaming and yelling all the stuff I had said to them out at the gate. I wasn’t sure what they were going to do to me!

When they had finished completely terrifying me, the fellow lowered me back down to the floor, and all of them started laughing. In hindsight, it’s a lot more funny now – at least for me. 🙂

What profession did you follow after your military service, and what are you doing now? If you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

Sitting up in the airplane’s cockpit, I started to notice something was wrong with this picture. There were two officers and one lowly enlisted man – that would be me. At 19 years old, being the radioman and in charge of all the Avionics on our plane was rewarding, but I realized I really wanted to get an education. I thought I would go into something like electrical engineering. It’s interesting how my interest changed when I was introduced to the field of psychology. I studied psychology and have a BA degree in Psychology from UNCC and a master’s degree in Marriage, Family, and Child Counseling from Azusa Pacific University in CA. I was licensed and in practice in Southern California for about eight years. We moved to Charlottesville, VA, and started another counseling practice, Virginia Center for Family Relations. I’m going on 50 years as a mental health professional. I continue working as a clinician and the Director in full-time practice. It has been a great honor to provide counseling to many folks in our community, including those who have served our country in uniform. You are welcome to learn more about us at our website at www.VCFR.us.

What military associations are you a member of, if any? What specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

Always ready! Keep your head up and anticipate the unexpected.

What I miss most is that I wish I had stayed in touch with the men I served with. If any of you read this, please feel free to get in touch. I would really love to catch up with you.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Coast Guard?

This is one of those once-in-a-lifetime experiences – do your best to keep in mind the purpose is to help you be more prepared for the work ahead. Do your best to form some friendships with others in your company. Together, the journey will go much better.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with?

With TWS, I was able to connect with one other fellow with whom I was with in boot camp. I’d sure like to hear from others. It’s been a lot of years since going through all that, and it would be fun to catch up and hear how your life has unfolded over these years.

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

0 Comments