PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

The following Reflections represents Capt Bill Darrow’s legacy of his military service from 1963 to 1983. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Marines.

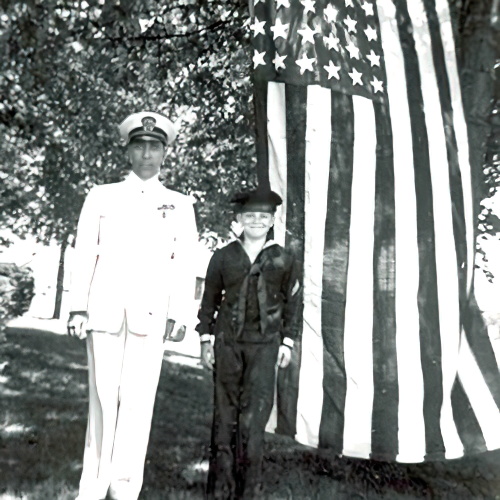

Both my parents were in the Navy during WWII. My Mother was one of the first WAVES, and my Dad was a POW at Bataan and an officer in the Navy. I have three brothers who were all in the Navy during the Korean War. During my grade school years, I attended Peekskill Military Academy in NY and was further schooled at home with Calvert School. I graduated from High School in Belvidere, NJ.

At 17, I briefly attended a Business School in Pennsylvania but soon got bored. Then, I decided to join the Navy and carry on the family tradition. There was a long narrow hallway in the post office where the recruiters were located, with the Navy recruiter on my right and the Marine Corps recruiter on my left. I stood in the hall between the two offices. Turning to my right to go into the Navy recruiting office, I noticed that the Navy Chief was wearing a soiled uniform. Next to him was a coffee pot that looked like it hadn’t been cleaned since the Spanish American War. He was overweight and didn’t seem to be too interested in the young man beginning to enter his office. Just before I walked into that somewhat messy office, I heard someone with a deep, commanding voice speak to someone else he called Corporal. I turned and saw the most chiseled-faced, lean man with a very short neat haircut and wearing a shirt with creases in it that could cut your finger on. I couldn’t help but stare at the very clean office with posters of fighting men, jets, carved Marine Corps logos, and an NCO sword hung neatly on the wall. Another man with fewer stripes on his shirt walked across the office.

The shine on his shoes was brilliant, and I couldn’t help but stare. He laid some papers on the organized desk and disappeared into the next office. In the corner of the room was a gleaming coffee pot, unlike the one in the Navy recruiting office. “You!” said the Marine GySgt as he looked up and saw me standing in the hall. “Yes, you,” he said again as I looked up in total amazement. “Come here!” This was a command, not a request. I responded with a smile on my face and entered a world I had never expected.

I always knew that I would someday join the Navy but never expected to do what I was about to do. He told me about the men in the posters and a little about what it took to be like them. Then he asked, “How many push-ups can you do?” Playing football in high school taught me all about push-ups, so I happily demonstrated them. Then he pointed to a pull-up bar located in his office. I was happy to put my chin over that bar at least five times. He seemed genuinely impressed. “Very good, and you say you’re a high school graduate too. Now, I want you to sit down and take this test.” A small booklet was placed in front of me, and within an hour or so, I was finished. He graded all my efforts and exclaimed, “Son, your aviation guaranteed!” His excitement turned to amazement as I then said, “But I don’t want aviation. I want to be one of them!” I then pointed to the poster with the grunt carrying the machine gun. He raised his eyebrows, smiled, and looked away for a minute. “Why, with these scores, you can do almost anything you want,” he said with a grin and a gleam in his eye. Little did I know what he meant by those jesters.

After discussing my future with this man who could look through a block of granite, I signed up for six years. This all happened on a Friday. That following Sunday, after church, I sat down to dinner with my parents. I had decided that now was the time I would announce my decision. My Dad smiled at me and said, “You joined up, didn’t you?” I’ll never know how he knew, but he was like that. “Yes, sir,” I replied with a grin. “I joined the Marine Corps!” That old saying about a deer in headlights best describes the look on my Dad’s face. My Mother, who had taken a very hot pot roast from the oven and who was on her way to the table, simply dropped the roast on the floor with the gravy and all.

Fortunately, we were able to salvage the roast, and we all had dinner, but you could cut the silence with a knife. Neither of them said much of anything, and I didn’t know just what to say. All I ever knew about the Marine Corps was that my Dad used to call them “Seagoing bellhops.” Still, I was full of what Gunny had told me and was excited about the literature I was given. That same day a show we watched on TV told the story of Marine Recon. “That’s what I want to do,” I said with an excitement in my belly I had never felt before. “You’ll never make it.” my Dad said as he watched the show. I was raised to never talk back to my parents, and I never did. Deep inside my spirit, my Dads simple comment lit a fire in me that culminated in a challenge that never went away throughout my entire career as a Marine.

I was promoted to PFC out of boot camp in Paris Island, but my parents didn’t attend my graduation. I was the outcast Marine in my family of Navy veterans. The years passed, and I always would remind them that it took two good Navy folks to make one good Marine.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

First of all, I would like to thank Billy Hillhouse and the TWS team for the kind invitation to allow me to share my military experiences on this site.

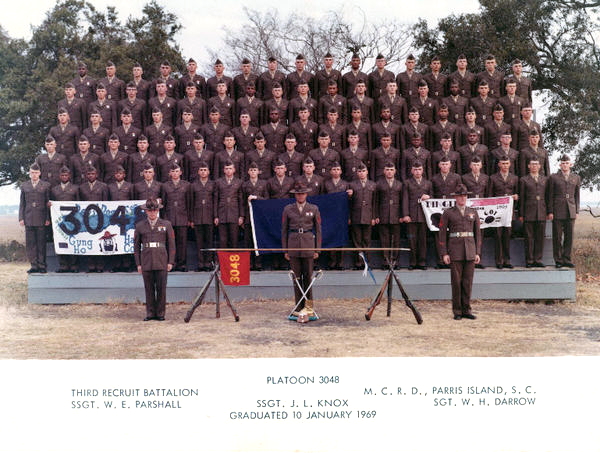

In August 1963, at the age of 17, I enlisted in the USMC for four years. Like all recruits, my very first day at Paris Island, SC, was the most terrifying experience of my life to that point. I quickly adapted and began to fit in. Within the first week, I was chosen to be the first squad leader. During the following weeks, I was chosen as the Platoon Guide and remained there until graduation.

One incident stands out that occurred when I was still in boot camp getting ready for the final field. I feel that I should mention this, for it affected all of our lives from then on. It was in the afternoon, and we were busy drilling on the parade ground in front of our barracks in the first battalion area we used to call Dodge City.

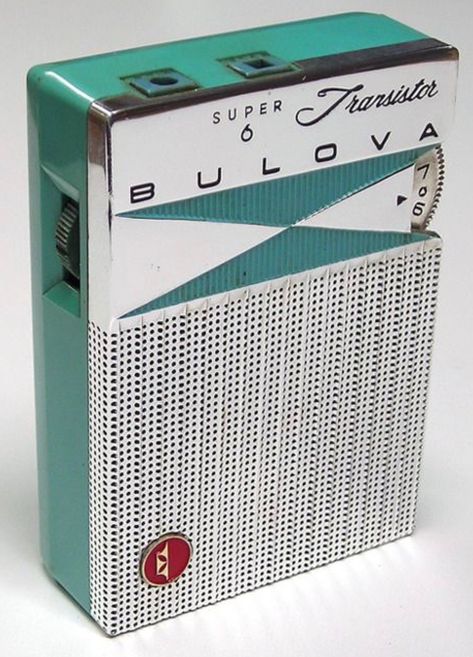

Sergeant Casteel, our senior drill instructor, ran across the field and told Sergeant Smith to Get em back in the barn! Everything stopped, and soon we were standing at attention in front of our racks. We never had a radio or television during those days, so we were virtually cut off from the outside world. Sergeant Casteel, Sergeant Smith, and Sergeant Sutis, our drill instructor team, all came into the squad bay, stood at the table, and placed a small radio on it. Then Sergeant Casteel turned it on, and we all listened to an announcement I didn’t believe.

President Kennedy had been shot and taken to a hospital in Dallas. The announcer went on to say that he had been shot in the head and that the police were looking for the shooter. As I said, I didn’t believe this at all. Some of us, including me, thought that another drill instructor was somewhere broadcasting it over that little radio, maybe for some sort of psychological test. As time went on, the announcement came that President Kennedy died as a result of his mortal wounds.

We were then told that since we were so close to graduation, we might be issued combat gear, stay as a unit, and be sent to Cuba or somewhere else because of a war that hadn’t been declared yet. Days passed before we all knew the truth, and this had really happened, but none of us were able to watch television or witness the historic news.

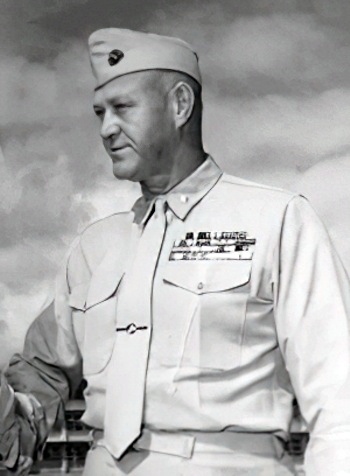

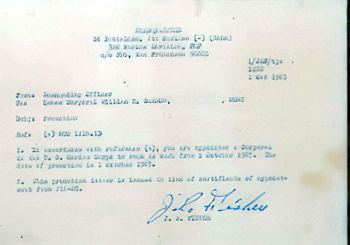

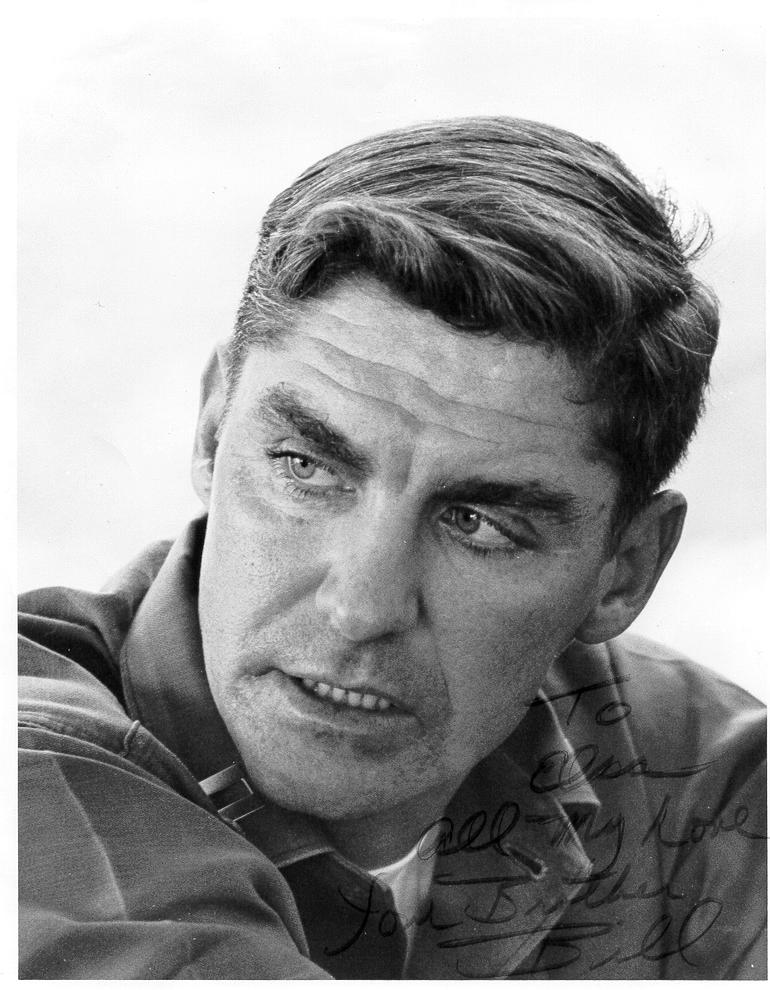

When we were first called Marine, I had my first meritorious promotion to PFC, and my career began. Within the first year serving as an S-2 Scout with the Second Battalion, Fourth Marines, in Kaneohe, Hawaii, I received my second meritorious promotion to Lance Corporal My third promotion came as a complete shock. One rainy day in Vietnam, I had just returned from a patrol, got my first hot chow, and was told to report to the C.P. Colonel J.R. (Bull) Fisher was sitting at a field desk. “There you are, Big Bear.” He said as I entered the tent carrying my mess kit and my hot cup of coffee, completely soaked from the rain

I thought I was going to go on another patrol and was there to get an overlay map and new orders. The S-2 chief did give me an overlay, then told me to report to the Colonel. Colonel Fisher asked me how I was and then proceeded to put paper in the typewriter in front of him. He typed the letter, took it from the machine, signed it, folded it, and put the folded copy in my mouth between my teeth. My hands were full with my mess kit, full coffee cup, and the new overlay.

“Congratulations Marine!” said Colonel Fisher. I thanked him, did an about face, and left the tent back into the rain. Lance Corporal Don Johnson was waiting for me outside the tent, so I motioned for him to take the paper from my teeth and told him to read what the Colonel wrote. I thought it was extra orders for our next patrol. Then Don began to read: From the Commanding Officer to me, Ref: (a) NCO 1416.1D you are appointed a Corporal in the U.S. Marine Corps, etc. I had just received the highest honor of my career. That little piece of paper meant more to me than any certificate, promotion, or commission I would ever receive. I was truly a “Magnificent Bastard,” as Colonel Fisher used to call the Marines of 2/4. He nicknamed us that right after he took command in Hawaii.

The following year I was told that I had been promoted to Sergeant. This happened during my last operation called Double Eagle. Lt. Col P.X. Kelly was the Commanding Officer of 2/4 at that time. Later, General Kelly became the Commandant of the Marine Corps.

On the very last day of that operation, I was the point for the Battalion heading towards our helicopter landing zone when I stepped on a mine. The booby trap failed to detonate fully, but my right ankle was broken along with my right leg. After some mix-ups in shipping me back to the states, I finally wound up in Philadelphia Naval Hospital. There I was to remain for some time while the Marine Corps decided what to do with me. They wanted to give me a medical discharge. That was out of the question, and I volunteered for every assignment possible to prove that I was still in good shape.

Reporting into the Philadelphia Navy Yard, I was surprised to learn that none of my records had caught up with me. To my new command, I was still a Lance Corporal. So, without too much argument, I simply fell into the routine at that rank and stood every post and did every job that rank demanded.

One particular Corporal acted tyrannically towards every one of lesser rank, and I didn’t get along with him either. He had been assigned to the Navy yard waiting for a humanitarian discharge and had managed to keep from going to Vietnam. He was somewhat overweight and kind of weak. For a few weeks, I lived in the barracks, stood my watches, and went along with the program. The other Marines were just returning from Vietnam, wounded veterans, or getting ready to go for the first time. We all got along just fine except for this one Corporal who believed that the NCO quarters were meant only for him, and one had to request permission to enter.

Then one day, I was told to report to Sergeant Major Brown. When I arrived, I was informed that the Colonel wanted to see me. Standing tall in front of the C.O.’s desk was funny because I didn’t know what to expect. He put me at ease and began to apologize for mistakes that had taken place regarding my rank. In front of him were my records, back pay for several months, Sergeant stripes, a couple of medals, and commendation letters from my last command. The Colonel asked me if I wanted a formation or just receive everything in his office, which is what I chose to do.

The Sergeant Major then instructed me to go to the tailor, who was located next to our barracks, and have those stripes put on my uniform. He also told me that they were to outfit me with NCO dress blues. I was also informed that my new duty station was to be right there at the Navy Yard and that I would probably serve the rest of my enlistment there.

It didn’t take me long to go to the tailor, and soon I was sporting my new stripes. The first thing I did was to march into the barracks and kick that Corporal out of the NCO quarters. All the other Marines were shocked to see me walking around wearing Sergeant stripes but very happy that I had taken over the section.

Everyone was happy about that except that overweight Corporal. The first thing I did was take him on a little run. I felt that he needed the extra exercise and to lose some of that excess baby fat. I never asked any man to do more than I could do. With my newly mended ankle and leg, it wasn’t easy for me to run, but with this added incentive, I did just fine. While at the Navy yard, I was assigned to be the Duty Warden at the U.S. Naval Brig. This was a “Red Line” Brig and one of the last of its kind. This building was also haunted, but I’ll save this story for another time.

Vietnam was getting worse as more and more servicemen were being killed and wounded. Because of the casualty rate, I was re-assigned once again. For the rest of the time I spent at the Navy Yard, I was an escort for fallen Marines. My job was to ensure that these Marines would receive a Military funeral and that their next of kin receive as much help as I could give them. These escorts lasted from several days to several weeks, depending on the situation and locations. I traveled by hearse, train, and jet from Maine to Puerto Rico and states in between. I had over 27 escorts, each one with Their own story. This was the saddest and most honored time I spent in the Corps.

My first enlistment ended when I won a four-year, fully paid scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania Art School. When I visited this university, all I saw were poorly dressed hippies lounging around in their classrooms. They smelled as bad as they looked, and I couldn’t see myself sitting in the middle of them. Dressed in my dress greens, wearing my medals and spit-shined shoes, I turned to the dean who had been showing me around and said, “No thanks. Semper Fi.” I returned to the Navy Yard, went into the Career Counselor’s office, and shipped over for D.I. school and six more years.

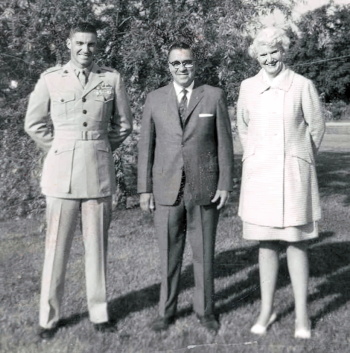

D.I. school brought more challenges, but I graduated and went on to be a Drill Instructor at Third Battalion, Parris Island, SC. About 18 months later, I won the ADI or Assistant Drill Instructor award and was promoted to Meritorious Staff Sergeant. At that same time, I had applied for the Enlisted Officer’s Commissioning Program. I failed all my boards because I would answer the questions as a Marine and not as a future officer.

An example of the question I answered wrong was: “Which officer that you know in the Corps would you most like to emulate.” Without hesitation, I replied, “Colonel J.R. (Bull) Fisher.” That was the wrong answer. The board was made up of young Marine Lieutenants who didn’t want to hear anything about (Bull) Fisher or (Chesty) Puller or other Marines like them, and they weren’t quite politically correct.

Another example of a question I failed was: “During a combat situation and a Marine was brought to you who refused an order, what would you do?”

My answer was: “Sir, it’s been my experience that Marines do not refuse orders in combat situations.” Again the same question was asked, and again I answered the same way. Once again, the question was asked by an irate Lieutenant. I said: “Sir, if a Marine was brought to me, still standing, and he had gotten past his Corporal and Sergeant, still refusing an order in combat, I would have an issue with that Sergeant who should, in turn, have words with the Corporal.” At the end of all my review boards, the result was that I was too enlisted-minded.

My Commanding Officer was a Marine named Colonel William Gately, and he knew me well. He had been moved to Regimental H.Q. when I went before those boards. When he saw those reviews, he took all my poor reports from those boards, threw them away, and wrote a personal recommendation of his own for me. Colonel Gately was also a Mustang and had served from WWII throughout Vietnam. I was very honored to have had a personal recommendation from him.

I was accepted to OCS. and received my Mameluke sword from all the men in my Officer’s Candidate School at graduation. My first duty station as a Second Lieutenant was “B” Company 3rd Recon Battalion. They were on their way back from Vietnam to Okinawa, where I joined them. When the C.O. of the company shipped out, I was chosen to take his place. This was a great honor that I cherished for the next 18 months. I was the most junior Company Commander in the Corps.

There was a C.O.’s stick that had famous Marine Officers who had once commanded this company like “Ding Dong” Bell, P.X. Kelly, and others. I added my name on the bottom of this stick as “Wild Bill” D with an arrow through it. This little brand had been mine all my life. I even carved it on a statue of a sleeping Buddha one night in a temple deep in the Vietnam jungle with a dead V.C. lying in front of it.

As a First Lieutenant, I was stationed at Camp Lejeune, NC. I worked in the “New” Brig that became a “Correctional Facility” in the new politically correct Marine Corps. They made me the Admin Officer, but I soon found a new mission. The inmates had no type of physical fitness facility, so I was able to let them build an obstacle course right within the prison compound. It was every bit as good as the one located at the beach for the Second Recon Battalion and became very useful for those who wanted to return to duty.

A new job was then assigned to me that I had never expected. I was put in charge of the main mess hall at Camp Lejeune as well as the Guard Officer for the base. There were two very good Gunny Sergeants, one an excellent baker and the other an excellent cook. “What would you need to make this the best Mess Hall in the Corps?” I asked on my first day as their C.O.

“Sir, give us a free hand and just keep us out of jail.” I smiled and said, “You got it!” Within a few months, our mess hall was the Best in the Corps, and the Commandant even visited us and presented the award.

Later that same year, I was assigned as the C.O. of Sub Unit Two. This unit consisted of all the Marines who had received bad conduct discharges, undesirable discharges, were waiting for a court martial or were otherwise in a bad condition. When I took charge, I learned that even the M.P.’s were afraid to check around our barracks at night. The only Marines who were not in trouble were the Staff NCO’s and the First Sergeant, and me. Seeing the situation, the condition of the barracks, and the condition of the men, I decided to begin a training schedule that began with a force march at 04:30, marching to and from chow, cleaning details, more P.T., and so on until lights out. At first, there were those who thought they would get out of the force march by going AWOL and throwing away their boots before they returned. This didn’t last long when they found themselves on that force march in their shower shoes. Then they would go AWOL but, on their return, would have kept their boots. That unit turned around, and some of those foolish Marines had even changed their minds about the Corps. They did all they could to stay, and many did.

My Captain’s promotion was next and a new billet. I was assigned as the X.O. of H.Q. Co. at Camp Lejeune, where I remained until 1972. During this time, I started the boxing team that made it to the Olympics. One of the boxers in that team was Leonard (Leon) Spinks, who I had promoted to Corporal. I also wanted to box, but the Marine Corps would not let an officer box, so I missed my chance to knock out Duane Bobick, who was fighting for the Navy at that time. I was upset that the Corps wouldn’t let me try out, so I jumped in the ring with Staff Sergeant Percy Price. Staff Sergeant Percy Price was one of the biggest, strongest fighters I ever knew. He once knocked out Cassius Clay. After the first round with him, he knocked me out too.

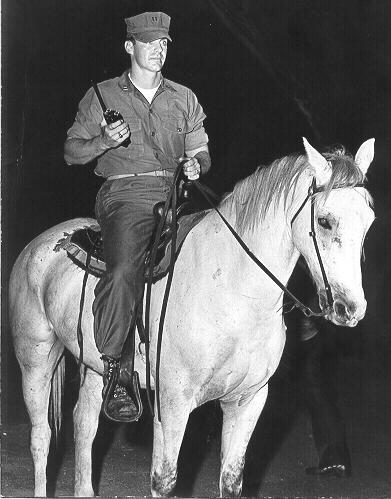

My last duty station consisted of three years at Subic Bay in the Philippines. These years brought adventure, excitement, and pure joy. I loved the Philippines. During this tour of duty, I was honored to have been chosen to be in charge of the detail that lowered the U.S. flag at the American Embassy, signifying the very last day of the 99-year lease the U.S. had on those islands and that they were now officially independent. I was also the Operations Officer / Security Officer for the refugee camp called “Camp Grandy” for the Vietnamese Refugees fleeing from a fallen Vietnam. I had 30 Marines and two horses to secure over 10,000 refugees. This was the most successful refugee camp of all the refugee camps established at that time.

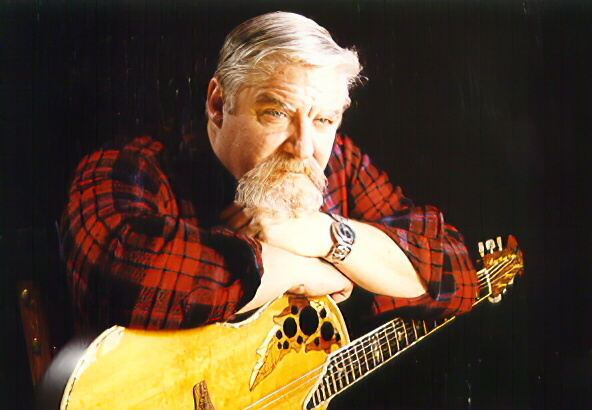

After being asked to write action scenes, dialog, and any other ideas I had about a movie that would be filmed in the Philippines, I ended up as the Military Technical Adviser/Stunt double and writer for the movie “High Velocity” starring Ben Gazzara, Paul Winfield, Britt Ekland, Victoria Racimo, Alejandro Rey, and Keenan Wynn. I was also on T.V. as one of the first Marlboro Men.

As a result of this movie, I was given the opportunity to be the Military Technical Advisor for the film “Apocalypse Now,” but I refused. After reading this script, I realized that it was far from any truth about the Vietnam War. I later discovered that the whole thing was based on a book about a crazy missionary in Africa. Francis Ford Coppola and I did not agree, and I told him so. There were scenes where American Naval personnel in the “Brown Water Navy” in Vietnam would clean a machine gun and then try it out, killing children who were playing along the shore. Other scenes showed Marines passing pot around while watching a USO show. I sent the script to the states, and as a result, there were no servicemen allowed to be used as extras in that movie. President Marcos allowed them to use the Philippine Air Force, but by that time, Francis Ford’s movie had cost him so much that he went bankrupt. I also had the opportunity to be in the movie “MacArthur,” but my schedule would not allow me to do it.

In 1975, I watched a movie called “Jeremiah Johnson,” and I knew what I wanted to do. The Vietnamese War was over. President Carter had just allowed all the war protesting draft dodgers who had fled to Canada and other parts of the world,

complete amnesty, and I was to be sent to Washington, DC as my next duty station. This was enough for me. All I wanted to do was head for Montana and get as far away from civilization as possible. I wanted to live like that Mountain Man simply I saw in that famous movie and raise horses. I resigned my commission three times before the Commandant of the Marine Corps paid a visit to the Philippines. After I explained my desires to him, he relented and told me that If I would add one sentence to my letter, it would be considered. The sentence was that I would remain a Reserve Officer in the Corps. After he left, I resubmitted my letter with that sentence, and it was approved. In 1976, I was discharged from the Regular Marine Corps and sent back to the states.

In 1987, I finally was discharged from the Marine Corps as a Captain that I will always be Once a Marine, always a Marine.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

“How do we fight these Marines? They never run, and they never smile.”

In 1965, I was a member of the S-2 Scouts or the Combat Intelligence unit of the Second Battalion Fourth Marines. Being part Black Foot Indian on my Father’s side, I was very proud to have been chosen to be a Scout / Pathfinder. After landing at Chu Lai, Vietnam, we established our command post on the west or jungle side of Route One. Our Battalion tactical area of responsibility, TAOR, encompassed the entire area where the airstrip was being constructed plus several clicks of jungle west of Route One. During the first few weeks, I went on several patrols.

On those patrols, we ran across several VCs, we were in a few firefights, and were shot at from time to time. We learned many lessons about scouting and patrolling. An example of lessons learned was that when we would come into our areas after a patrol, the first man would step out and count each member of the team crossing the wire. If there were more than expected, the last man or men would be shot. The VC sometimes would tag on to the rear of returning Marines and sneak their way through the wire. This happened to other Marine patrols from the different units but never to the Scouts.

Other lessons learned taught us to be extra cautious about setting off claymore mines we had set on the perimeter. Sometimes VC would turn them around, make noises on the wire, and the unsuspecting Marines would set the claymore off, only this time, the deadly part of the mine would be facing the Marine’s position.

I once watched a Chu Hoi, turncoat VC, put on a demonstration by crawling under tanglefoot and concertina wire which was considered impossible to do. Tanglefoot was a maze of barbed wire set only inches from the ground that covered several feet in all directions. You couldn’t get over it, and crawling under it was next to impossible. He did this in record time, wearing very little clothing. He then went through triple strand concertina wire as if it weren’t there. I knew we were in serious trouble.

The Vietnamese who were displaced from their villages in our TAOR, tactical area of responsibility, was moved to an area called Chu Lai New Life Hamlet. This compound was located directly in front of our CP to the west of Route One. One day I was sent with a corpsman to that village where a little girl had been shot through the hip by a VC sniper. I found the child next to the hamlet on a trail, picked her up, and took her into the village where the corpsman attended her. When I asked how she was, he simply said, “Well, she’ll never have any children.” The girl was approximately seven years old. I then went to where she had been shot to see if there was any indication of where her assailant might have been and maybe even get lucky and find him. What I found was an odd cut in the grass, kind of like crop circles but smaller. These markings were made up of large Vietnamese letters meaning WARNING!

Later that same month, our TAOR was expanded to include three hills we called Catfish One, Two, and Three. These hills were the foothills right next to the jungle that extended to the mountains. I was sent with my Scout team consisting of Cpl. Daniels, Cpl. Edwards, and Cpl. Kolb, who was soon due for transfer. Our hill was Catfish Two, and getting there was no easy walk. The Scouts had to carry a heavy piece of equipment called AN/TPS-21 ground surveillance radar unit plus our own equipment. We had mules to haul most of our equipment; however, one of the mules turned over on the steep hill, so we had to carry everything. Since I was the most junior man in the unit, I had to carry the heaviest piece of this equipment, plus I caught all the tough jobs like stringing concertina wire, digging holes, etc.

When we arrived at the top of this barren hunk of rock, the sun seemed to pick this very spot to shine its hottest. There was no shade, no cover, and very little water. Just as I laid down on the jungle side of the hill for a little rest, a shot was fired, and we all scrambled for our weapons. I then went to the other side of the hill, where I saw a young Marine holding his bleeding leg and claiming that he had had enough and wanted to go home. He had just shot himself in the foot with his M-14, and his GySgt wasn’t too happy about that. I thought that the Gunny was going to finish the job with his .45, and I believe that he truly considered that, but he put the gun away and simply told the radio man to call for a med-evac helicopter to be sent for this cry baby. I later learned that the cry baby Marine lost his foot due to his stupidity.

Later that evening, I saw what I thought was a cloud moving fast from the ocean side of the hill heading towards the mountains. As I watched, someone hollered, “Get Down!” just in time for a huge swarm of insects to fly directly at us. These insects were everywhere, but within a couple of minutes, they all headed for the jungle and parts unknown.

At the bottom of Catfish Two, next to the jungle, was a stone well that contained some of the coolest and best-tasting water. There were also ancient stone carvings that looked like a scene from a movie about an oriental jungle. My job was to fill as many canteens as possible and carry them back up the hill. I did this with the greatest pleasure because the water was like gold.

We established our position and dug in as much as we could on that very hard hilltop. Later we were supplied with sandbags and other equipment that allowed us to make better positions. The Scouts were put on the side of the hill closest to the jungle with our radar equipment fully functional.

One night when I was on the radar machine, I heard something moving closer to our position where we had concertina wire. I listened and couldn’t believe my ears. It sounded like a tank moving through the jungle right towards us. A Lieutenant also listened and confirmed my suspicion, so he decided to call in an 81 motor attack, which is what we did. There was a section of 81s with us on that hill also, along with a 106-millimeter recoilless rifle. Mortars began to fall, and with the explosions, we heard lots of commotion, thrashing around, and blood-curdling screams coming from that tank. The next morning I saw what was causing all the strange surges of sound in my headphones. We managed to kill one of the biggest water buffalo I had ever seen. The other Marines on that hill thought this very funny and made a water buffalo medal out of C ration wire and hung it on our Radar unit. It remained there until we finally packed it up. That Radar unit did not work very well in a jungle environment, especially when it rained so this was the first and last time I can remember using it.

Other things happened on Catfish Two such as the time I had to dig a four-holler on the scenic side of that rocky hill. It took me the better part of a day just digging that hole. I finally was able to build that wooden head made for that purpose and placed it over the hole. It was a real work of art, or so I thought. Behind it was a large bush, the only one on top of that hill, and in front of it was a beautiful view of the Chu Lai airstrip and the ocean. What I didn’t know was that just on the other side of that bush was that 106 mm recoil-less rifle.

I was determined to be the first to use my creation, so right after I had finished constructing it, I simply took some toilet paper from my pocket, pull down my utilities, sat down to enjoy the evening view. Then I heard someone holler: Clear the back blast area! Clear the back blast area! Clear the back blast area! I looked around and wondered what was going on when KABOOM! I found myself flying through the air and landing in the middle of a triple-strand concertina wire with my pants tying my ankles together. The beautiful four-hole head had collapsed and my butt was on fire.

Marines who heard the commotion from my yelling came only to find me strung up in that wire. The sight was so funny that many of them simply fell to the ground laughing. At the time I didn’t think this was very funny, but fortunately, I wasn’t hurt badly. This was the funny thing that happened on that hill.

Because the ground was so hard they decided to fix the four-holer, leave it where I had put it, and move their 106 so that it wouldn’t happen again. We found another use for the four-holer later.

Being the most junior man in my unit also found me on listening posts at night, usually with another Marine from the platoon that was stationed on that hill. One night it started raining very hard. I took up my position down the side of the hill that was the steepest with another Marine who I hadn’t known. We were ordered not to put any rounds in our chambers by the Lieutenant who was afraid of accidental discharges. I had been there long enough to know that this was a stupid order so for the first time in my military career, I disobeyed an order, chambered a round, and put my M-14 on safe. That other Marine, who I believed to be the skinniest Marine I ever saw, did likewise. We weren’t afraid of the Lieutenant as much as we were being taken with an empty weapon by the VC. We knew that we wouldn’t see him until morning anyway because we were so far away from the lines by the wire and it was raining buckets. We kept covered as much as possible with our ponchos but it was impossible to keep dry. There were only two of us on that listening post on that side of the mountain and because of the rain we couldn’t even see the top of the hill or the other Marine positions. All night we kept a 50% watch with one of us trying to sleep while the other stood watch.

Around 0400 with the rain still falling, I sat up to take my turn on watch when shots rang out, grenades went off, whistles blew, and men started hollering everywhere. Both of us grabbed our weapons but couldn’t see anything. Then my buddy was hit in the arm. I shot back, not knowing what I was shooting at, and hit a VC three times in his face. That I did see from the flashes of my M-14. I do not believe that they knew we were there because the VC simply ran up the hill on both sides of us, hollering and throwing Chi Coms, communists’ hand grenades.

Later I found out that 81s were firing almost straight up with mortars falling almost straight down on all of us. They had been on the north side of that hill while I was on the southwest side. Directly behind me, just to my right were three Marines in a hole. The VC threw Chi Coms which blew two of the Marines out and killed the other Marine who remained in the hole. The VC ran around the top of that hill hollering, throwing grenades, and getting killed. There was communications wire and twine wrapped around the ankles of all of the dead VC who was on top of the hill. Other VCs who were at the lower part of the hill pulled their comrades down when they were hit.

One Marine Corporal, an 81-millimeter mortar team leader, ran to his position when one of his own men turned, drew his .45 pistol, and shot him dead center. It just so happened that as the Corporal ran, his flak jacket, which hadn’t been shut, came together just at the right time and stopped the bullet that lodged in the jacket virtually shutting it together. The Corporal wasn’t wounded but it did knock him unconscious for a time. The Marine who fired the shot re-holstered his weapon and continued to drop mortars down the tube.

After this attack, the VC ran down my side of the hill and retreated into the jungle. I hadn’t shot back up the hill because I couldn’t tell who was the VCs and who were the Marines but on their way back down the hill, a couple of the VCs ran into me and my buddy. One of them stabbed me in my right hand but he never made it passed my position. My buddy was in shock and kept saying, they shot me in my skinny right arm or words to that effect.

When the rain subsided we had several dead VCs on top of that hill and pieces of others strewn around the area. There were several unexploded grenades all around. I guess the rain kept them from going off. We very carefully collected all of the unexploded Chi Coms and put them in an area where they could be blown later. We carried the bodies of the dead VC and put them in that famous four holler I had dug just a couple of days before. They looked more like store manikins than human beings because they weren’t bleeding very much and had stiffened in odd positions. The smell was similar to the smell of steel. This is hard to describe. It’s the kind of smell that you can taste in the back of your throat. Flies were beginning to quickly gather around their open wounds but we were hardened to this. It’s amazing how fast one can adapt to death. None of us said very much just got down to business and did our duty.

My wound wasn’t very serious then and I did not want a Purple Heart for it. My father had had a history of heart trouble. I was afraid that a telegram informing him that I had been wounded might have caused him to have another attack. I even threatened the corpsman to keep quiet and not report anything about my wound so he simply dressed it and wrapped my hand with a bandage. He was very busy with the other, more seriously wounded Marines getting them ready for a Med Evac.

There were also some AK47s and a few brand new Thompson Sub Machine guns that we found here and there. Colonel Bull Fisher then arrived on top of that hill and I gave him one of the Thompsons. I also gave a Thompson to the Catholic Chaplain who I knew very well since his assistant was a good friend of mine. Although Chaplains were not supposed to carry firearms, this one did. He feared nothing. When I would come back from one of those long patrols sometimes I would visit my friend at the Chaplains tent. He used to call me Bill which was unusual for an officer and would give me some wine to drink that was a special treat.

That morning, just before we buried those dead VC, just as the sun rose I saw a very strange sight. Below the 81’s position was a valley and another hill with little vegetation on it. Lying on that hill was the biggest red-haired ape I saw. We all watched as he seemed to be sunning himself. He laid on his back, stretched out his long red-haired arms, and enjoyed the rising sun. This was very strange given what had just occurred on Catfish Two.

After Colonel Fisher left, I went with a reinforced platoon on a patrol towards the area where I had seen the VC vanish into the jungle. When we stopped at that stone well at the bottom of the hill, we found some dead VC were floating in it; So much for cold water.

For a couple of days, we followed a blood trail towards a village in the jungle and found bodies and pieces of bodies hastily hidden in hay stacks and bushes along the trail. All in all, we counted 24 dead VCs from their first attack on Catfish Two.

We heard later that a VC currier had been caught carrying a message to a North Vietnamese General that read: “How do we fight these Marines? They never run, and they never smile.”

On the third day, my hand was swollen and was hurting. I couldn’t move my fingers and knew that it had become infected. When we returned to the Battalion CP, I checked in with the corpsman. The head corpsman looked at my swollen hand and immediately sent me to B Med, located on the beach at Chu Lai next to the ocean. There I had my first operation where my wound was re-opened, and penicillin was shot directly in my hand. I was then transferred to the Army hospital in Nha Trang, Vietnam, where I received another operation to save my right hand. More penicillin and bandages and lots of sleep were prescribed. I did enjoy the first hot chow and cold drinks that I had since we landed.

In the ward where I was were several other wounded veterans. One of these poor guys cried and screamed all night long. We all complained about the noise until the nurse scolded us for being so heartless. She informed us that this Marine had been cleaning a rocket pod on a helicopter when another Marine accidentally touched off one of the rockets. The rocket blew off the young Marine’s family jewels and left a burnt hole in their place. We never complained about the noise again.

While at that hospital, I met Clayton Ramone. He was an Army Special Forces Sergeant and had taken a bullet to his arm. We had shared the same Escape and Evasion school in Hawaii at the same time, so we were old friends. Since we were both ambulatories we were allowed one day’s liberty. We went into Na Trang to see the sights and found ourselves on the beach. Na Trang is considered the Riviera of Vietnam. It was a beautiful place with little huts all along white sandy beaches, all selling cold beer and such. I felt guilty about being there while the rest of the battalion was in such misery at Chu Lai, so my liberty was short-lived.

While in NhaTrang, I overheard my doctors discussing my transportation back to the states. As soon as I heard that, I managed to get to their supply room. I checked out all the gear that had accompanied me, including my rifle. I then made it to the airstrip and hitched a ride on a helicopter to Da Nang. There wasn’t anything going to Chu Lai the rest of that day. From Da Nang, I managed to get another ride on another chopper to Chu Lai. After landing at Chu Lai, I found a jeep that was going to my battalion. On that jeep ride, the driver stopped when I spotted a .45 pistol sticking out of the sand. We carefully moved it from a distance in case it was booby-trapped and found that it was o.k. It was probably dropped by someone. That was a real find and a trophy that I wish I still had.

When I arrived at our area, the Sgt Major saw me and told me to report to the Colonel immediately! When I reported, I found out that my parents had written their congressman, and a search had been conducted for me. It seemed that no one knew where I had been. At the same time, there was an AWOL, absent without leave, alert sent out for me from that Army hospital in Na Trang.

My parents were worried about me because they hadn’t heard from me for some time. I explained to the Colonel that I couldn’t write with my hand bandaged as it had been. I also explained that the Army doctors were going to send me to the States, and all I wanted to do was return to 2/4 and stay with the battalion.

Colonel Fisher listened to my explanation and told me that he would write to my parents. He further ordered me to write to them twice a week or at least have someone write to them until my hand healed. Then he said that he would take care of the Army AWOL charge and not to worry about it.

I was given light duty for a few weeks until that bandage could come off, but I still went on patrol and kept watch with my fellow Marines. I did have someone write to my parents and inform them that a poisonous spider had bitten me on my right hand. That was the reason that I couldn’t write, but it was getting better, and I would write soon. I learned later that they had received a telegram anyway. This was just the first telegram that they would receive.

Once when my hand was still healing and wrapped, I was on a mountain looking over the north end of our CP across the rice paddies when a long flame shot across the field. I called it in and was told to report this if it happened again because no one was supposed to be in this area. A few minutes later, this flame shot across the field, covering a large area. I couldn’t see where it was coming from as the night was very dark, and there were no lights except for that monstrous flame. The only thing I could think of was a dragon spitting fire. Then I was informed that a “Flame Tank” had moved into that area and that they were burning off bushes in front of their position. That was my first experience seeing a flame tank in action.

On August 17th, 1965, Operation Starlite was launched. The S-2 Scout teams were attached to different companies as attached units. My four-man team was made up of L/Cpl. Reigner, L/Cpl. Estmahan, L/Cpl. Don Johnson and I, their team leader. We were attached to H Company and put on helicopters for the assault.

There has been a lot written about Operation Starlite, so I won’t go into detail about facts and figures. It is easily found on any Google search. I will say that during that whole operation, LCpl Reigner was shot in his shoulder, and the rest of my team was not hit, although we were all right in the middle of it.

The other Scout teams were with Echo Company and Gulf Company. Hotel Company was nicknamed Hospital Company after this operation. Several hundred NVA and VC were killed and wounded. A tank fired on a grass hut where a machine gun had been shooting at us. It blew off the grass to expose a several-foot thick concrete pill box. There were a few of them in this area, all placed so that the Marines were caught in a crossfire.

LCpl J.C. Paul was the first Marine to receive the Medal of Honor as a result of his heroic efforts in protecting those Marines who had been wounded, although he had been wounded several times himself.

Most of the helicopters that brought us in never made it out. Long poles were stuck in rice paddies outside of the village. As we started to land, I wondered what those poles were for, but I soon learned. When a chopper would land, the pole would tip over, setting off an explosion right under the chopper. These were helicopter booby traps. The pole we knocked down didn’t go off, and I made it to a ditch next to the rice paddy.

Later, we used tanks as Med Evac vehicles, and some of them were disabled from motor attacks. Once, we shot into a whole tree line, and all the trees and bushes died. They were NVA. On the following day, how I got to Route One is still a blank. I can’t remember a huge block of time, but I was covered in blood, and I was just walking down the road in a daze when Colonel Bull Fisher stopped his jeep and asked me if I wanted a ride. I must restrain myself otherwise, this will turn into a book.

In October 1965, Colonel Bull Fisher promoted me to Corporal. Around that same time, the Scouts, which had consisted of three four-man teams, was re-designated as the first Raider Platoon and then consisted of three 10-man squads, of which I was the first Squad leader. We called ourselves The Bull’s Raiders. Our mission was similar to the original Scouts; however we would go on extended patrols and live in the Villages, working with the ARVIN, Army of the Republic of Vietnam, and PFs or Popular Forces. We were also some of the first Marines to work with Kit Carson Scouts. These were former VCs who defected to our side. Our job was gathering intelligence, capturing live VCs or NVAs on what we called “snatch patrols”, and were designated as a quick reaction force that could travel light and fast to any situation. Most of the Raiders were all handpicked and very proficient in their skills, like the M-60 machine gun, Snipers, etc.

Bunkers were built all over Vietnam, and I became a construction wizard with sandbags. My bunkers were all arranged with everything very handy like aiming stakes, grenade shelves, sleeping quarters, great camouflage, and all. It never failed that after I would make one of these palaces of sand, we would have to move out, and some other Marine would enjoy our labor.

Once, after constructing one of these very fine bunkers, we had some extra time, so we decided to set up a couple of 55-gallon drums filled with what we called fu gas. Fu gas is a mixture of jet fuel or some other type of fuel, ivory soap flakes, and other ingredients. We then tied claymore mines or C-4 on these cans and ran the wire attached to the explosive device back to our bunkers. We had these cans strategically located on each side of a valley so that the fu gas would be blown all over should anyone try to come through the wire at the bottom of the valley.

That night we heard a noise behind us that sounded like clinking. I looked but could see nothing. Behind us was the entire CP, so I wasn’t worried about anything there. Later I heard another noise coming from the wire at the bottom of the valley. I alerted the other Marine in our bunker to stand by. I then decided to set off that fu gas and light them up. When I did, the whole valley was covered in flames when all of a sudden hot flames shot over our bunker that causing the sandbags to disintegrate. I was afraid that our grenades would cook off, so that another Marine and I scrambled out of that bunker and headed up the hill behind us.

I ran my helmet directly into the front of something that felt like a huge boulder. As I reached up to feel what it was, I couldn’t believe what had just happened. I was like a blind man feeling this huge bolder, or whatever, that had suddenly appeared. A flame tank had moved into position right behind our well-camouflaged bunker and didn’t know we were there either. They had opened up when I exploded the fu gas barrels and almost cooked us alive.

I stood up and walked around that tank and scared the Marine sitting on the tank. “Where in the hell did you come from?” he asked as I stood there with my helmet still smoldering.

“Right in front of you! You stupid x@#$%!” I answered. Then we all started laughing. It was all kind of funny in a crazy way.

We were returning from a long-range patrol and making our way around a village when a young girl met us on the trail. “VC, VC!” she said that sounded like; “bee she, bee she” in her broken English. Then she pointed towards the village and ran back, disappearing around a hut.

I placed my squad in positions behind a rice paddy dike and looked into the village to see any sign of the VC she was talking about. L/Cpl Don Johnson, lying next to me, and I spotted a VC sitting in a tree with his back to us and a long rifle across his lap. It looked as though he was watching for us to come from the other side of the village, but we fooled him.

Don then raised his rifle at the same time I raised mine. “Hold on now.” I whispered, I saw him first.”

“No, you didn’t,” said Don. “I saw him first, and he’s mine.”

As we whispered back and forth for a minute as to who would shoot this VC out of the tree, my radio man said, “Hey, you two, just shoot him.”

I told Don that I was senior and would take the first shot. If I missed, it would be his turn. I also decided to simply wound the VC and take him, prisoner. Don agreed and told me to go ahead and pull rank. This conversation was all in fun, but one would think that it was very dangerous to carry on.

I aimed in and shot twice with two successive shots. The first bullet hit the VC behind his leg, but he flipped over backward and the second round caught him high in his chest next to his neck, killing him instantly. He was dead when he hit the ground.

We waited to see if there had been any more VC in the area, but all we saw was several people gathering around that dead one lying under that tree. We moved cautiously towards the village where I was met by the Village chief. He presented me with a Vietnamese flag, which I still have, and told us that over 200 VC had occupied their village the day before. He further said that they had left and headed back into the jungle but had left that one back to warn them about any Marine patrols.

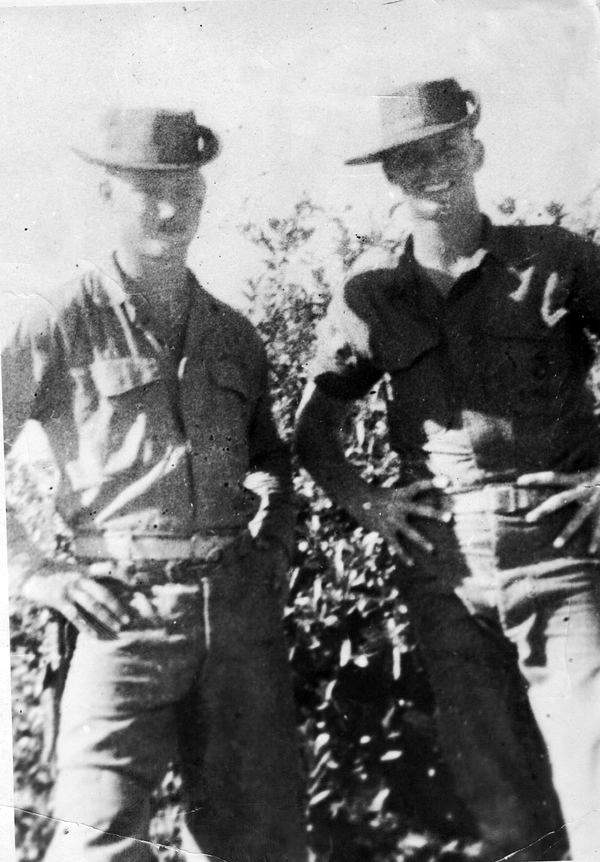

Corporal Daniels told me to pose with the dead VC and that he would take my picture. The picture I’m presenting with this question was the one taken at that time. I called this picture “The Last VC” because this one had been the last one left by his comrades in that village.

Somewhere in a box of pictures, I have a picture of that little girl we met on the trail at the exact time she was telling us about the “Bee She.” I wish I could remember where that box was.

Another picture taken of me was taken by some newspaper photographer who saw me crossing a small river while on patrol. I had a carbine in my hand, and the picture only showed my hand holding this carbine as I sank into the river. The only thing dry was this rifle.

I think that one appeared in Navy Times.

We lived in the village for a time working with the P.Fs. and the ARVINs in the area setting up ambushes, capturing VC, and trying to win the hearts and minds of the people. On one small operation with no name, I was working with an ARVIN unit when we stopped on a rice paddy dike just on the outside of a village. All of a sudden, two of the ARVIN troops must have seen something, got up from their position, ran around me in the rice paddy, and headed for the gate that was closed in front of us. I hollered for them to stop, but when one of them hit that gate to open it, it blew up. Both of those Vietnamese troops caught the brunt of the explosion and were killed instantly. Part of that gate, a small piece of bamboo, broke off and flew through the air, hitting me in the forehead. The force of the blow knocked me on my butt. I wasn’t hurt but only stunned a little.

When I got up, I moved to where the two dead Vietnamese were but saw nothing moving in the village. We then proceeded to go through that village with no more incidences. Coming out on the other side, I felt that I was sweating a lot, whipping my forehead and seeing the blood. The skin on my head was cut, but I hadn’t felt it. I took my t shirt and wrapped my head like a Revolutionary War soldier and went back to the other village we had been living in, where a corpsman attended to me. Again I told him not to report my cut, and he didn’t, but I could have received another Purple Heart. I do have a nice scar to prove it.

Once, while on patrol with my Raider Squad, we were told to “Get Down.” When your told to “Get Down.” In Vietnam, you do. So we did, and the next thing we experienced was several 2000 lb bombs dropped on a mountain range in our vicinity. It was our job to count hair, teeth, and eyeballs after that air strike. We weren’t told that that air strike would be that large or dropped from those Air Force Jets. Walking into those drop zones was like going from a lush jungle to the dark side of the Moon. There weren’t any bodies; there weren’t any signs of life or any foliage. It was all gone. Someone once took a picture of me sitting on an unexploded bomb, smiling and eating a can of C rations.

I remember when they first used Agent Orange in Vietnam around the jungle areas just northwest of Chu Lai. We were sent into those areas to inspect. Nothing was growing. It was like a large trail had been cut through the jungle where that stuff had been sprayed. I believe that this was somewhere around the Ho Chi Minh Trail. No place to hide.

Another combat experience happened when I had just crossed a hill and set in for the night. I observed movement on an adjacent hill and notified my CP using resection to plot my position. I was asked if I could direct fire, and I told them that I would adjust. I gave the co ordinance, and after the first round was fired, a white puff of smoke coming from the target. It was a direct hit, so I simply said, “Fire for effect, fire for effect.” The next thing I heard was the sound of a Volkswagen flying over our heads, and it landed on top of that mountain. Then several other Volkswagens joined the first one, and all we could do was get down. The earth shook like I had never felt it before. My radio man was bounced from where he was with his helmet, landing in the spot where he sat while he landed several feet away. We were all shaken when I grabbed the radio and said, “Cease Fire! Cease Fire!”

When I was asked for a target description, I answered with these words, “The target is gone.” The whole top of that mountain had been flattened. I thought I had been talking to an artillery unit stationed at Chu Lai. What I had been talking to was the Battle Ship New Jersey that had just come on station. Now that was an experience!

Once while we were resting from patrolling on hill Catfish One, we had joined some other Marines stationed there. A Marine sniper who had been positioned on the mountain armed with a 50 caliber sniper rifle wanted to take a break from his position to get a cup of coffee. He asked me if I would take his place, and I was happy to oblige. The position where he was sitting was between some boulders and not easy to get into. Once I was seated, I looked through the scope towards a village that was estimated to be over 1200 yards away. There was a Lieutenant standing behind me with some binoculars looking in the same direction when we both saw what looked like a VC walking back and forth carrying a radio with a whip antenna. “Do you see that?” he inquired.

As I looked through the scope mounted on the 50 cal. I said: “Yes, Sir, I sure do.” Watching for a moment I decided to let the sniper back behind his gun when he, now standing there with his canteen cup full of hot coffee, told me to take the shot. The Lieutenant said, “Go ahead and shoot.” So I sighed in with that rifle and shot once. Looking through the scope, it looked as though the VC I shot hit the deck and didn’t move. Immediately a patrol was sent to investigate and about an hour later reported that an old man, carrying a pile of sticks on his back, had had his head blown off. One of the sticks he was carrying was long and thin, stuck in the pile of wood on his back, resembling a whip antenna coming out of a radio. That was one of the longest shots recorded at that time in Vietnam, well over 1200 yards. What that old man was doing walking back and forth on that trail outside that VC village, I’ll never know.

We would go on several patrols around this mountain. A new man reported to me to join my Raider Squad. He was brand new to Vietnam, too, so I told him to carry the M-79 and to watch the man in front of him and do what he did. This was his very first patrol. When we started to walk on a rice paddy dike at the bottom of the hill, I heard the unmistakable thud of an M-79 being fired behind me. There were three Marines between that new man and I strung out on this dike. Then I saw an M-79 round bouncing along the dike right next to me. It followed the trail like someone had skipped a rock across a pond. We all dove for cover because this round hadn’t gone off yet. An M-79 round is a small grenade shot from a large tube shotgun-type weapon that, when shot, will travel approximately four feet before it is activated. When it hits something, it explodes with shrapnel spreading out in every direction, killing, maiming, and wounding everyone within a six-foot+ radius. That round simply hit the dirt next to that new Marine’s foot and bounced along the trail next to the patrol. Fortunately, it never went off.

On an M-79, one can move the trigger guard out of the way, exposing the trigger for quicker access. This was an unnecessary thing to do at that time, but it is exactly what this Marine did. We nicknamed him “Dinger” after that. Needless to say, I wasn’t very happy with Dinger.

On another occasion, we were manning bunkers along our front line. There were two of us in each position. Dinger was in the bunker to my right, and the rest of the team was spread out accordingly. The night became very dark as usual when we heard some movement on the wire in front of us. All of a sudden, Dinger hit a pop-up flair but forgot which way to aim it and that flair shushed right into my bunker, lighting us up like never before. Needless to say, I wasn’t very happy with Dinger. Just last year, I found out that Dinger had become a Lt/Col and retired from the Corps???

On Christmas 1965, the bridge at Ahn Ton was hit by several groups of VC. They attacked by the river in boats and attempted to kill all the Marines located in bunkers on both sides of the bridge. I and my team were the first to get to the bridge the following morning. When I arrived, I pulled several dead VCs off of a Marine I knew well. He was Sergeant Casteel, my former Senior Drill Instructor. He survived, and I learned that he retired as a Captain in the Corps.

On another patrol with a Company of Marines, we were walking across a rice paddy dike when something caught my eye. It was a simple piece of grass that was tied to a piece of bamboo. It looked out of place, so after I investigated further, I found that on the other end of that piece of grass; under the water, were a bunch of steel punji stakes. These were unusual for our area. I had never seen steel ones before, so I turned them into our intelligence folks. Because of those unusual punji stakes, they were able to identify the North Vietnamese Army unit that had moved in to this area. This was more evidence to begin Operation Harvest Moon. I still have one of those punji stakes.

Later that same month, I was on a deep patrol carrying a ground-to-air radio. We had just come around a mountain when two F-4 fighters passed overhead. We popped smoke to signify our location when one of the fighter pilots informed us that there were several of the enemy climbing all over that mountain. We left that area, but while we were still on that mountain, I observed Marines walking towards a village across a rice paddy. I also saw several Viet Cong in the village. I called the F-4 for close air support on that village, and he dropped what ordinance he had taken out several VCs. The Marines proceeded towards the village, and we moved fast to leave that mountain.

We then walked back to Route One to rejoin our unit. The 2/4 had been located at the beach in our first hard-back tents at Chu Lai, and we had several cans of beer waiting for us on our return. We were issued two per day, and we had been gone for several days. This was American Beer and cold too.

In 1969, when I was in the Basic School as a Second Lieutenant, Major Rivers, who had also been on Harvest Moon, showed a film of this action to our Basic School Class. The film had been taken from other Marines who were behind an M-60 on the other side of the village facing the mountain where I was. It showed the air strike and the Marines attacking the village. Then Major Rivers asked me to stand and introduced me to the other Lieutenants as the Marine who had called in that air strike. Later that year, Major Rivers, who was the XO of Third Recon Bn., was responsible for my appointment to his unit. “B Co. Third Recon Bn.” was my first duty station as a Marine Officer.

Once, we were put in bunkers just outside of the Chu Lai airstrip. This was considered our backyard and somewhat of rest from patrolling. I was in a bunker with another Marine from a different outfit. Our bunkers were spread out about 30 or 40 feet apart. After dark, around midnight, a VC sniper began to shoot in our direction. His rounds were hitting between our bunkers as though he really did not know what to shoot at. For some unknown reason, I decided to do something very stupid. I told the other Marine in my bunker to watch for the flash of the sniper’s gun and aim for that. Then I climbed on top of our bunker and lit a cigar. After a couple of puffs that lit up the sky, a round loudly cracked right next to my head. I dove back into the bunker, landing on top of the other Marine who was about ready to shoot. He never shot, and I just sat there wondering why I had done such a foolish thing. I figured that I had been in Vietnam too long.

I had saved up lots of money from my pay that had ridden on the books for several months, So I decided to buy myself a Christmas gift at the Chu Lai PX. It was a real Rolex watch that I proudly wore for the next week or so.

While scrambling up a very muddy hill, being shot at by another sniper, my watch band broke, and my brand new Rolex went under my left boot, buried in the mud. I didn’t have time to look for it either. Just then, a black Marine who was directly in front of me was hit in his left leg. He didn’t seem to notice it until we got to the top of that hill when I said, “Your hit!”

“Where?” he asked. I told him in his leg. He looked down at his bloody leg, let out a holler, and fell to the bottom of that muddy hill. I had to go back down the hill and carry him back to the top. He was a very heavy Marine. I should have kept my big mouth shut. Fortunately, whoever had shot at us moved on and didn’t stay around to take another shot.

In January 1966, Operation Double Eagle began. This was the first amphibious operation that I had been on since we landed in Vietnam. Operation Double Eagle is also easily accessible on the internet, so I will spare these details also.

When 2/4 landed, we were transported by Am-tracks up the beach to an area outside of a VC village. There we took up our positions when several Marines in my unit started getting sick. We all had malaria; however, we all were taking our malaria pills for some time. That is the only way I knew that it was Sunday. That was the day we took our pills. Anyway, I lost two of my squad to malaria on the first day. There was incoming fire from the village all night. The next day I walked through elephant grass with bullets flying overhead. We couldn’t see anything for the grass until we finally made it to a clearing where a trail led into the village.

The day before, other Marines had passed by that same way and had received heavy resistance. As we went down the trail, we found a hole directly in the center that was about two feet deep and two feet round. In the bottom of that hole was a Marine helmet sitting upright. I took a long pole and turned that helmet over very carefully in case it was booby-trapped. Inside of that helmet was the top of a skull that had very red hair. A corpsman that I had noticed a couple of days before on board ship had that color hair. I thought at the time that he had the reddest hair I had ever seen, and now I was looking at it once again. We took the helmet and sent it back to the rear.

Later that day, we went through the village and saw a dead VC in front of a hut with some family members crying over the remains. My team was acting as the point of the battalion that day.

Coming to another part of the village, one of my team stopped us and pointed to what looked like a mound of dirt that looked like the opening to a tunnel. We were not about to go passed it without checking it out. I motioned for us to take up positions around the area, and I approached the opening. I could hear noises coming from this tunnel, so I hollered for them to come out.

After the third time of giving whoever was in the hole orders to come out, I threw a Willy Peter Grenade in it and watched in the distance for any sign of the white smoke coming from anywhere else where there could have been another escape opening. The only smoke that came out was located where I had thrown the grenade. This signified that this was more like a bunker than a tunnel.

After the smoke cleared, I sent a tunnel rat, the smallest Marine who could fit in the tunnels, into that hole. After a minute or two, he threw out a small dead girl about two or three years old, still burning in places from the white phosphorous. After the child was a woman, I believed to be her mother. After her came three dead VC with weapons and all.

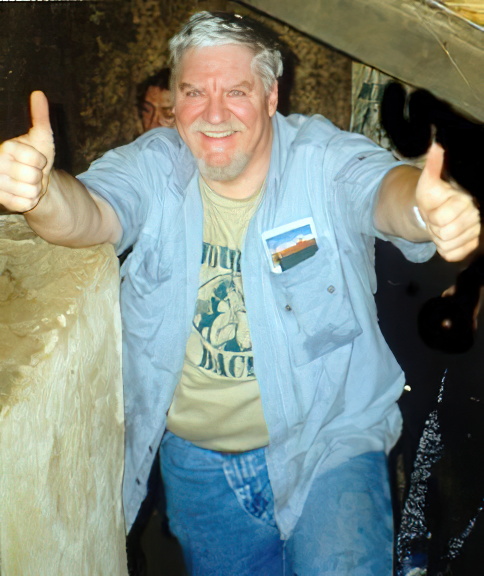

This dead child has haunted me for years until I was finally able to forgive myself for her death. In 1999 I returned to Vietnam with Evangelist Dave Roever. There I experienced going into the Cu Chi Tunnels, a place that I never thought I would ever go!!!!!

One of the groups of people who went on that trip with us insisted that I go down that dark hole. Her name is Patty Smith, Corky Smith’s wife. Corky was also a Veteran of Vietnam. Corky was a Ranger on the ground and, as an Army Aviator, was shot down over Vietnam and managed to escape and evade the enemy. He is also a great aviator and worked for the Government inspecting air disasters.

As a result of Patty’s prodding and praying, I was finally able to bury that child and the demons of war that tormented me for years. If not, I would never have been able to write these accounts.

Operation Double Eagle lasted for several days. As a matter of fact, I had been 15 days overdue to rotate back to the States on the last day of Double Eagle. This operation was a combined Army / Marine Corps operation. We walked, and they flew.

On one occasion, we had taken position along a trail just at dusk. I took up a position in a ditch facing a very dark jungle. Late that night, I heard someone holler, HALT! Then all hell broke loose. Green tracers whizzed over my head only a few inches away, and an explosion went off then more tracers and more fire. I couldn’t see a thing, so I and the rest of my team just kept down. We were in a terrible position, especially at night, because our visibility was zero. The next morning I walked up to the trail and found one dead PFC and a badly wounded Gunny Sgt who had lost a leg. There were two or three dead VCs along the trail, one of which was torn up badly with one foot resting next to his head and several other disgusting wounds throughout his body. His eyes were open, and his mouth was slightly opened.

That young PFC, who was fresh from the states, had alerted the VC walking down that trail by hollering, “Halt!” It really wasn’t his fault because this is what he had been trained to do in the States. He just forgot that this was Vietnam.

We received word that we were to eat cold C rations and then move out, so I sat down next to that dead VC and began to open my box of C rations. Directly across the trail from me sat another Marine who had just taken the place of one of those I had lost from malaria. He was new to Vietnam also and had never seen anyone killed before. He didn’t seem very hungry. I looked at him, smiled, and then began to open my can of rations. At the same time, I began to talk to the dead VC. I wanted to get that young Marine’s attention and let him know that this was normal. He had to snap out of it. As I talked to the VC, I continued to eat. After chow, I lit a cigarette. Since I didn’t smoke, this was unusual, but I knew what I was doing. Then I placed the cigarette between the teeth of the dead VC. It fit perfectly as though he was really smoking it.

The other Marines in my team talked to the dead VC also, and soon that new guy, as we used to call Marines, who had just arrived in Vietnam for the first time, started to come around. We received the order to Saddle up and move out. I left that cigarette smoldering in that dead VCs mouth and moved out with my team.

Several years later, I learned that the whole battalion, including Colonel P.X. Kelly, passed by that dead VC with the cigarette stuck in his mouth and only laughed. All laughed except a Lieutenant who became very upset. He was new also and vowed to find out who had done such a terrible thing. Someone told him that they thought that one of the Scouts had done that and that if he hurried, he could catch him way up front. He never tried and probably found out that even the Colonel thought it was funny.

We finally made it to our LZ, landing zone. The whole battalion was air-lifted out of there. My team and a few others were last to leave. When I boarded my chopper, I saw what I thought were sparks coming from the side of the helicopter. Then I realized that these were rounds bouncing off the side and some going through. When we took off, a round struck the gunner sitting by the open window next to his machine gun. It hit him in the right shoulder and went through his body, killing him instantly. We left that LZ with one dead Marine and one wounded CoPilot.

When we landed at the next LZ, I rolled off that chopper into a rice paddy. Then I ran toward a small trail next to a small hill. When I got there, I saw what I thought were two or three boy scouts wearing the same kind of bandannas running up the hill away from me. They weren’t carrying any type of weapon, so I didn’t shoot them. I turned and realized that I and my team had been running in the wrong direction so I ran back across the rice paddy, directing the other Marines to follow me which they did.

We joined the other Marines at that time and moved out to our next location. I’ve often wondered if those boys I saw running away from me that day were really VC but I guess I’ll never know.

On another occasion, we had stopped next to a blown-out cement bridge. I was summoned by the Colonel, who wanted me to swim with a Major to check out the bottom of the river. The Major was from Amtraks and wanted to see if he thought Amtraks could cross safely. Someone told the Colonel that I was the best swimmer in the battalion.

One of my Marine Snipers then crawled out on what was left of that blown-up bridge as far as he could, and the Major and I went in the water. The whole battalion was lined up along the river watching. This river was very wide, and the current was strong, still, we swam out to the center of it, and the Major began to dive to the bottom. All of a sudden, rounds started to hit the water around us. We dove for cover, but one can only hold his breath for so long.

There was one hut located on the other side of the river. The rifle fire was coming from there. I remember only one small window in that hut and watched flashes light it up as someone shot out of it.

From the battalion side of the river came one shot of a 3.5-inch rocket launcher. A 3.5-inch rocket launcher used to be called a bazooka. As I floated in that river, dodging bullets, I watched as the rocket flew through the air. It hit directly in the center of that small window of the small grass hut and blew it to smithereens. The whole battalion cheered at this awesome feat, and the Major and I swam back with his report. Amtrack couldn’t get across that muddy riverbed.

We walked for seven miles through elephant traps, banana groves, and other sights I hadn’t seen before. At one point, we were so hungry that we ate the coffee that came in our C rations, paper and all. We finally came to another village that contained barrels of peanuts. After filling our pockets with those green peanuts, we went on.

This time it was up a very steep hill. On our way up L/Cpl, Don Johnson developed blood coming from his mouth. He was later taken out of the field, and I didn’t see him for several years. That was the most miserable climb I ever experienced.

L/Cpl Don Johnson had already received a Purple Heart earlier that year. Before operation Double Eagle L/Cpl Don Johnson was a member of my squad and my best friend, earlier that year, we were on patrol on the outside of a village and stopped in a Vietnamese cemetery. I decided to set up an ambush site at this location and leave L/Cpl Johnson with four other Marines to take up positions on the other side of the village that night.

Shortly after he left, we set in our position. Then just as the sun started to set, we heard shots come from the village. There were two bursts of rifle fire, one from an AK47 and the other from an M-14. It sounded like a whole magazine of rounds had been fired.

I called the radio man from Don’s team and was informed that they had one Ford and one Cadillac. The Ford was the code name for a dead VC, and the Cadillac was the code name for a wounded Marine. I then found out that it was L/Cpl Don Johnson who was the one wounded with a bullet to his head.

All that night, I didn’t sleep or even close my eyes. I thought of how I would go back to that village, get the village chief, and cut his heart out. He had informed us the day before that there was no VC in the village. He lied. My radio man had to practically sit on me until the first light when we could finally move out. That was a very long night.

As soon as the sun rose, I went through the village and saw Don Johnson sitting in the middle of the village drinking Vietnamese Whiskey. He was shot by a lone VC hiding in a bush directly in front of him as he walked down the trail. When the VC jumped up, he started shooting, and so did Don. Don got a small nick next to his right eye while the VC was literally cut in half, one half falling to the left and the other half falling to the right. This was the second time Don had been wounded in the same place, a nick next to his right eye.

Now back to the top of that terrible hill, we had to climb where we lost Don Johnson. As I said, Don was my best friend.

When we were on top of this hill, the Army made its way to our position riding in their helicopters with their heavy artillery and all. They even had ice chests full of beer and other cold drinks that they would not share. We, on the other hand, had nothing. We even had to get water from the creek and put halazone tablets in it so we could drink it. The only thing good about this was that we finally could get a good night’s sleep because we were in a secure position, or so we thought.

We pitched our ponchos like tents and turned in. The next morning I decided to take my team’s canteens to a small running creek just down this hill and fill them before we moved out. This was the first time in Vietnam that I didn’t carry my M-14 because I felt secure with all the Army artillery and helicopters in the area. When I started to fill the canteens, a bullet hit a rock very close to me. For the next few moments, I was dodging left and right with canteens flying in every direction. Bullets hit the ground all around me, but I wasn’t hit. Then a short lull and the sound of an M-14 went off, causing me to hit the deck again.

This time it was one of ours, and I soon was able to stand. When I approached the top of the hill, I saw two Marines just standing there. Right in front of them were two dead VCs lying just behind some boulders, dead. One of them was armed with a carbine. Then one of the Marines threw an empty magazine to me and said, “This one’s yours.” I learned that the VC had emptied this magazine at me and was in the process of reloading when the two other Marines walked up on them and put an end to their plans.

We walked along that mountain range until we came to an area where we could actually see the ocean again. While we rested, we saw a Vietnamese with his elephant walking through the rice paddy way off in the distance. On further inspection, we could see that this particular elephant was carrying an anti-aircraft gun, and this meant that he was the enemy.

The 81 mortar platoon was soon enacted and started dropping those mortar shells in their direction. They bracketed that elephant and his handler so that the elephant started to become very agitated. We all watched as that poor VC tried to take care of that very scared elephant, but those rounds just kept getting closer. They would move one way, then the other but it was no use. We all started laughing at this spectacle until that elephant was hit with one of those rounds. Then it wasn’t funny anymore.