PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

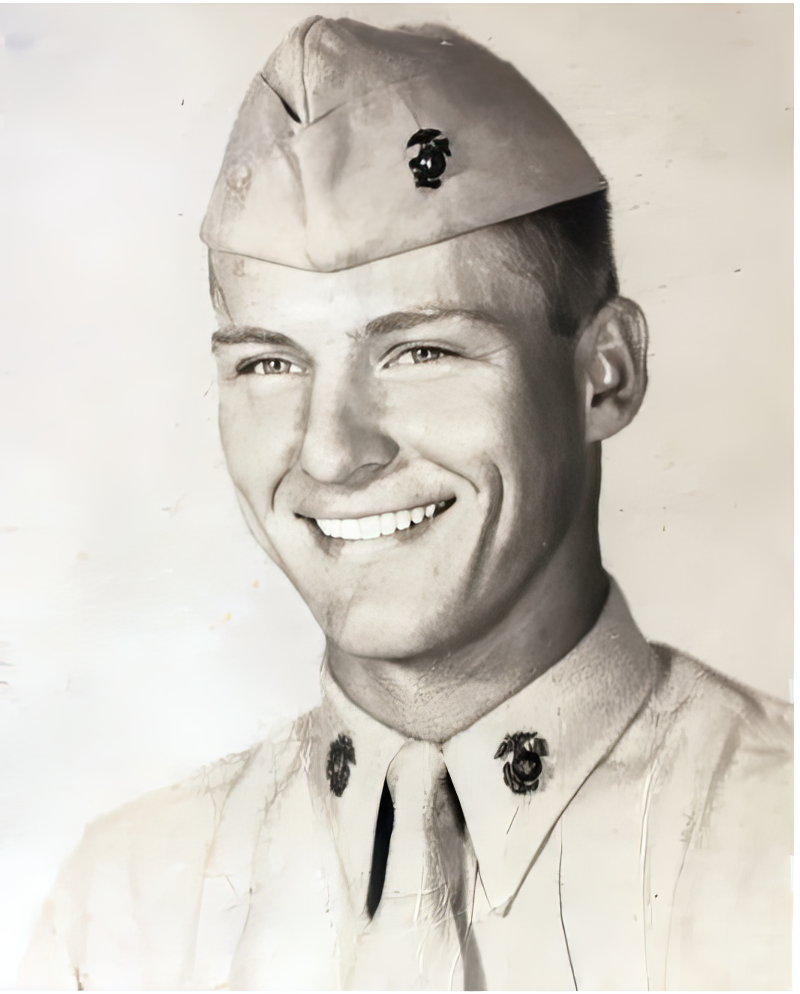

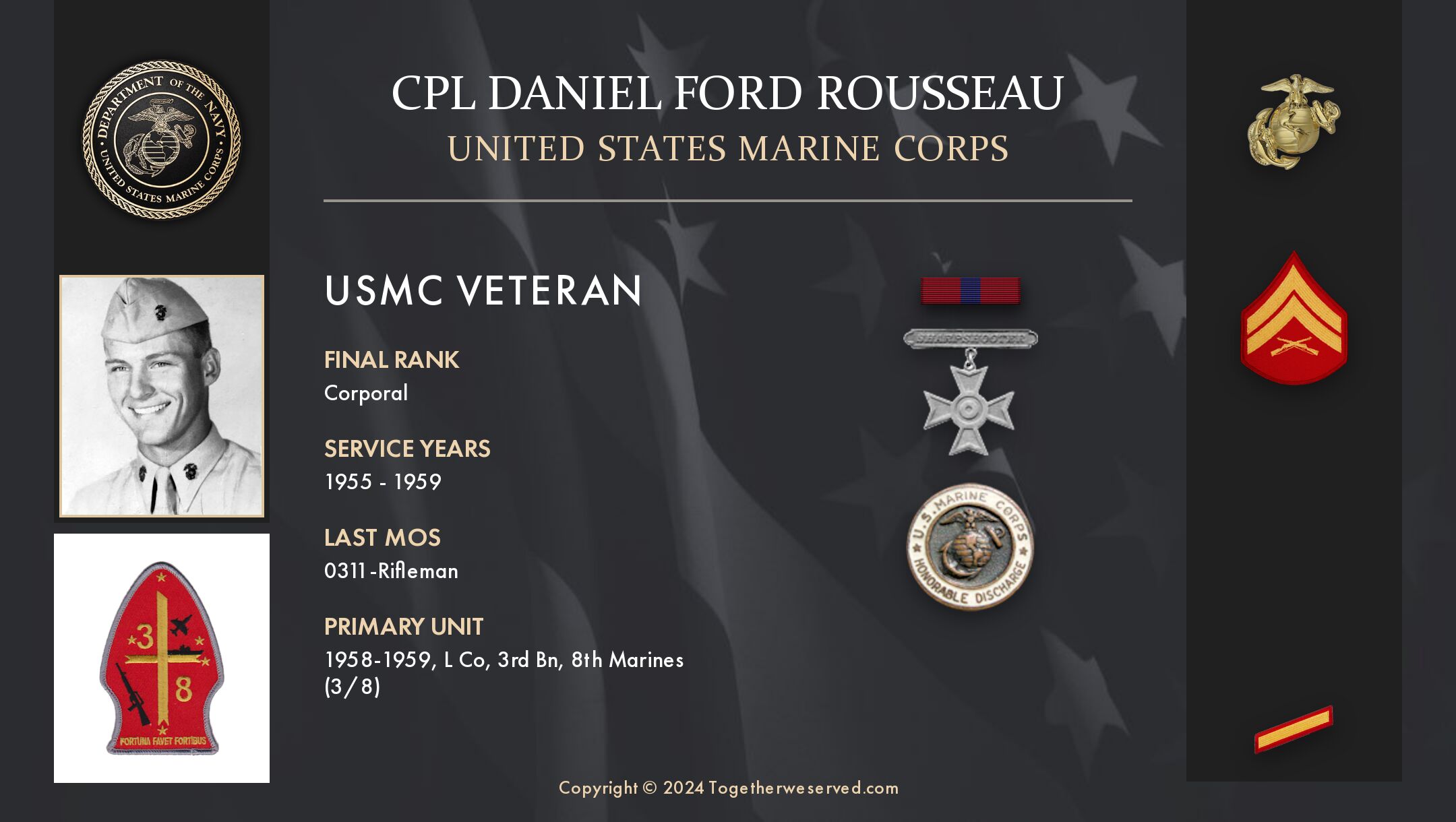

The following Reflections represents CPL Daniel Rousseau’s legacy of his military service from 1955 to 1959. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

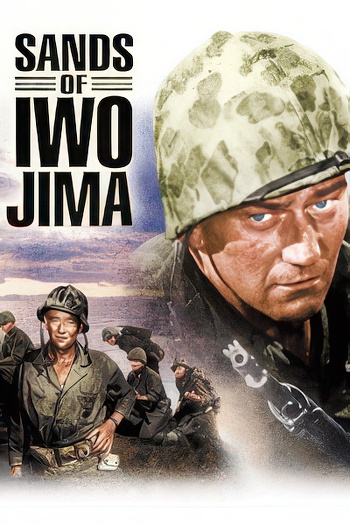

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Marine Corps.

The movie “Sands of Iwo Jima.” We were twelve-years-old when a friend and I came out of the movie theater and agreed that we would join the Corps together when we were old enough.

In 1955, my senior year in high school, I joined the 99th Special Infantry Company, our local Reserve unit. That is where I was recruited by then SSgt. H. Gene Duncan.

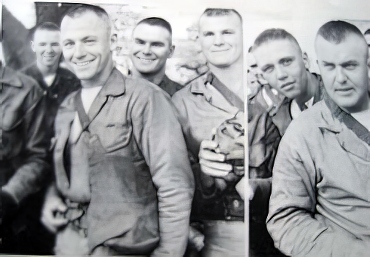

A year later, my boyhood friend and I enlisted. We went through Parris Island, ITR, and Sea School together, then aboard the carrier USS LAKE CHAMPLAIN CVS39. After sea duty, he was assigned to a battalion of 6th Marines, and I went to 3/8. I only saw him once after that. He made the landing in Lebanon in the summer of ’58.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

We know that of the millions and millions who have served as Marines, the vast majority serve one enlistment and then return to civilian life.

I fully intended to ship over when my enlistment was up because I wanted to go on Embassy Duty. In 1959, I was still single, making $160 a month as an E4. Life couldn’t get any better.

When I began exploring the re-enlistment options, I was at the main side hospital at LeJeune, recuperating from having broken my ankle on the last play of the final football game of the 1958 season. A young lieutenant, my platoon leader, was all Gung-Ho to get credit for signing me for another six years. One day he practically sprinted into the hospital ward, armed with pen and papers. “I got you what you wanted, Sgt. [at the time an E4 was still a Sgt.] You sign here, and you’re guaranteed Embassy Duty. You’ll go for State Department training and then to the embassy in Tokyo.”

I had specified I wanted to go to Tokyo. Now, here it was, a signature away from being real. I later discovered all that the Corps was guaranteeing was embassy duty—not the specific location.

“Great,” I replied. “Now when my two years at the embassy are finished, I want to go to . . . ” The Lieutenant never gave me a chance to complete my sentence. He said, “After the two years, you will be assigned COC.” I asked where COC was, and he explained it meant Convenience of the Corps. He said, “After Tokyo, you will go to the 3rd Marine Division on Okinawa because you’ll go to FMF, and Okinawa is the closest.”

I cannot explain to this day that I didn’t want to go to Okinawa. “How about I do an FMF tour at Pendleton or back here at LeJeune?” I asked. Nope. I would be going to the 3rd Division. It seemed final, the way he said it.

So, I didn’t sign the papers that day. Or the next. Of course, 99.999999 percent of the Marines on active duty in early 1959 had no clue that Vietnam would loom so large within five years. I certainly didn’t. It wasn’t the thought of fighting in Vietnam that made me change my mind. I didn’t want to spend time in Okinawa. I know that sounds crazy, but that was how my 22-year-old mind was thinking back then.

At the last minute, I applied for admission to the University of Florida and was accepted. The day I left LeJeune, I took a bus to Gainesville, Florida, and was still in my wintergreen uniform when I arrived there and registered for the second semester.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

No combat. But in October 1956, immediately upon boarding the carrier USS LAKE CHAMPLAIN, we sailed to the Med, along with the FORRESTAL, to reinforce the 6th Fleet. The reason? The Hungarians were staging a major uprising against the Russians in an attempt to gain their freedom. We sailed into the Med, within striking distance, while the United Nations pondered their response. When the United Nations voted not to interfere, Russian tanks rolled into Budapest and put down the revolt. We sailed to Norfolk, VA, returning in time for Thanksgiving.

In April 1957, trouble erupted in Lebanon. We were in Livorno, Italy, but immediately weighed anchor and sailed for the eastern Med. Marine Detachments aboard our ship, the FORRESTAL, the battleship IOWA, and heavy cruisers BOSTON and ALBANY, were activated and made ready to go ashore along with the battalion of Marines already assigned to the fleet. Negotiations temporarily cooled things off, and no landing was conducted.

1958 was an interesting time to be a young Marine. The Corps was working hard on their new concept known as “Vertical Envelopment.” The carrier I served aboard, the USS LAKE CHAMPLAIN, was designated to be loaded with helicopters [I don’t recall the type] and sail to Turkey’s coast. From there, the helicopters flew from our decks to the nearby ships carrying FMF Marines, and there they loaded the troops and carried them to the coast of Gallipolis, where NATO Turks were in defensive positions. Remember, this was before we had aircraft carriers designed as launch platforms for helicopters and Marines. It was a patch-work method of bringing Marines in by air. Marines today would look at what we did and scratch their heads in wonder. But you have to realize, every new tactic had its beginnings somewhere.

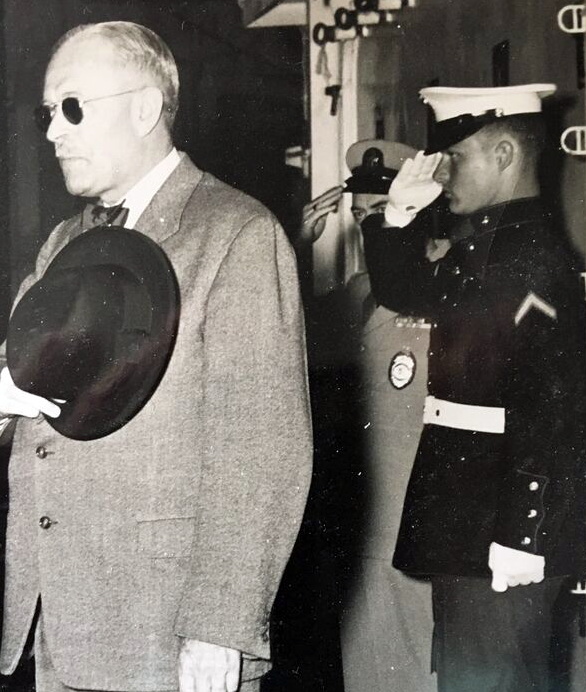

Later, in June of 1958, just as I was completing the NCO Leadership School at LeJeune, President Eisenhower sent a battalion of the 6th Marines ashore in Lebanon to confront an insurgency. All of Camp LeJeune went on alert. At almost the same time, Vice-President Nixon was in Venezuela, where an angry mob surrounded his motorcade. A unit from the 2nd Marines was air-lifted to the carrier VALLEY FORGE, waiting off Onslow Beach.

Did you encounter any situation during your military service when you believed there was a possibility you might not survive? If so, please describe what happened and what was the outcome.

July 1957, there was a fire aboard the USS LAKE CHAMPLAIN. We had entered the harbor at Marseilles, France, on Bastille Day and dropped anchor. I was the Captain’s orderly on duty, so once his official car and the shore patrol vehicles were loaded on a barge, I would go with them and be ready to drive the Captain when he arrived. At the last minute, the other orderly asked to exchange duty. I agreed.

That meant that when the fire broke out, he was the one aboard the barge taking the vehicles to fleet landing, not me. High-octane aviation fuel had somehow leaked out onto the water on the starboard side of our ship. The Bos’n announced the smoking lamp was out, and when he did, probably someone tossed their cigarette overboard, a natural thing to do, normally.

Almost immediately, the water on our starboard side roared with flames. The barge containing the vehicles was completely enveloped. My buddy who was was riding ashore had seated himself in the small “school bus” the shore patrol used. At first, he thought about staying in the bus, then decided it could explode at any minute, so he dived into the flames and began swimming through them the way we were taught in boot camp. He survived, but his face and hands were badly burned. He was rescued and taken to a hospital ashore, then flown to Memphis, TN. I never saw him again. Had he not asked to change duty assignments, I would have been on the barge and in the middle of the fire. I’m certain there are millions of near-miss stories like this that other Marines have experienced, whether in combat or peacetime.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

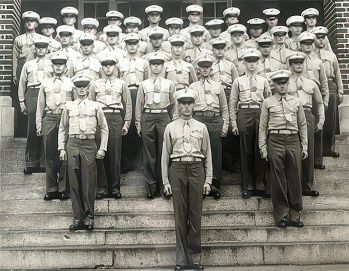

I loved my time at Marine Barracks, NNSY, Portsmouth, VA, for Sea School. All spit-and-polish. Colonel A.A. Vandegrift, Jr. was the commanding officer. When I was there in the fall of 1956, those Marine Barracks were the second oldest in the Corps, second only to Headquarters, Marine Corps. Sadly, the old building has been demolished.

The next favorite was serving aboard the carrier USS LAKE CHAMPLAIN as a Captain’s orderly. Luckily, I served under senior officers who were veterans of WWII. Great duty and a great experience. Thanks to my sea duty experience, I had the opportunity to climb to the top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa; drive to the top of the Rock of Gibraltar; gaze at the works of Michelangelo and DeVinci; attend the bullfights in Barcelona and Majorca; walk the steps of Athen’s Parthenon; follow a monk through the candle-lit catacombs beneath Rome; stand in St. Peter’s Square; walk through the Colosseum, and listen to the mournful calls to prayer in Istanbul as winter winds whistled down the Bosporus River.

I met some terrific guys in the Corps, one of whom married my middle sister. He’s deceased now, but there may still be some old Marines out there who served with him—Sgt. Major Charles W. Gill. Maybe if the Internet and websites like TogetherWeServed had existed after I left the Corps, I could have remained connected with many of my old friends.

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect back on to this day.

I was a disciplined kid who began at age six, working for my father, a man with a quick temper and a hard hand. He was too old for WWII but was the civilian equivalent of a DI. The lessons I learned from him reinforced my Marine Corps training, especially by my Drill Instructor Sgt. Ralph Bowling still serves me well.

A couple of years ago, I fired a handgun for the first time since I left active duty in 1959. I am left-handed but always fired a weapon right-handed. The handgun was a .38 revolver. When I tried to fire it, I discovered I couldn’t squeeze the trigger— arthritis in my trigger finger made it impossible. I had two choices: either go home or try using my left hand. I had never fired a handgun or shoulder weapon left-handed. But I did that day.

When we had finished firing at 15 and 25 yards and sending thirty rounds into each target, I found that each target had one round outside the bullseye. The range instructor asked where I learned to shoot. “The Marine Corps,” I told him. He said, “Well, that explains it, doesn’t it? It always comes down to sighting, breathing, and squeezing, just like they taught you. Take those targets and put one on your front door and one on the back door.”

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

I tied for first place in my Sea School class and finished as Honor Graduate in my NCO Leadership class in June 1958.

While aboard the LAKE CHAMPLAIN, I was supposed to have been awarded a meritorious promotion to E4 after I sighted a torpedo fired at us as we were sailing out of the carrier basin at Mayport, Florida. Of course, it was a dummy torpedo, the first one fired at us as part of “war games” with the USS SEAWOLF. Had it been real, it would have sunk us, thereby blocking the carrier SARATOGA coming out behind us.

When I saw the torpedo’s wake, I was on the bridge, standing next to the Executive Officer. “Sir,” I said, pointing to it. Commander Longino yelled an order to the helmsman, and the stern began a sharp slide to port, changing the angle of the bow and thereby causing the torpedo to miss us by a whisker.

Somehow, our Marine Detachment Executive Officer, a Lt. W**D, managed to find some way to squelch the paperwork, and I did not receive the promotion. Every so often, you find an officer who doesn’t understand the value of “taking care of the troops.” Our Marine Lieutenant was definitely what was known back then as a Cocker Spaniel Marine.

I was very proud of having spotted the torpedo’s wake before the lookouts did.

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

Without a war, medals were few and far between. The Good Conduct medal was all I rated. However, I was always rather proud of it because I knew Marines who never rated one.

When I graduated at the top of my class at NCO Leadership School, I was given a K-Bar. A ceramic bulldog was painted as if he was wearing dress blues and the designation: Honor Graduate, NCO Leadership School, Camp LeJeune, NC, 1958. I’ve always been very pleased and proud to have those mementos.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

SSgt. H. Gene Duncan, USMCR. He enlisted me into the Reserves during my senior year in high school in 1955. He also advised me a year later, when I was ready to go active—get a discharge from the Reserves and go Regular Marine Corps. So, that’s what I did. He loved Rudyard Kipling’s poems, and I still have the book “Barracks Room Ballads” Duncan gave me. “Gunga Din” was his favorite, and he recited it all the time.

Gene finished his degree and got a commission, and served in Vietnam, where he was badly wounded and retired as a Major. In Korea, he had been in a mortar platoon.

When Operation Desert Storm broke out, he petitioned to return to active duty. He was turned down. When the Commandant concurred, rejecting him because of hearing loss, he replied, “With all due respect, Sir, I don’t want to listen to the f***ing Iraqis. I want to shoot them.” Duncan did not sway the Commandant.

What he loved best as an “Old Gyrene” was visiting Parris Island during Thanksgiving and Christmas to talk with the platoons. In my day, that would have been almost like having Chesty Puller come talk to us.

Duncan also wrote several books, like “Brownside, Greenside.” If anyone asked him what the uniform of the day was, he would respond: “Dress blues, tennis shoes, and a light coat of oil.”

Almost every Marine will say he had the “badest Drill Instructor that ever wore the uniform.” Sgt. Ralph Bowling scared the crap out of us, and you knew he meant business, but everything he did was aimed at turning us into effective Marines. I suppose that was true of our other DI’s as well, but Sgt. Bowling had a way of doing it that made me want to do better and not because of fear. He retired a Captain, and I’m sure he was an outstanding officer, but to those of us who were the maggots when he was an E4 on PI, he will always be Sgt. Bowling, a title rendered with the utmost respect.

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

My former Drill Instructor, Sgt (now retired Captain) Ralph Bowling, Parris Island, and Sgt. Bob Doyle and a few other guys from my boot camp platoon are the ones I’m in contact with. Also, there is SgtMajor Philip C. Smith, a junior high and high school friend. We hunted and played football, and we were in the Reserves together. Smitty left for Parris Island a week after we graduated in ’55 and retired in 1980.

I’m also in touch was a Navy Corpsman who was involved in the recovery of bodies from the fire aboard the LAKE CHAMPLAIN in 1957.

Truthfully, I’m not sure how many others I served with are still alive. I search for them on TogetherWeServed, but time has taken its toll.

Can you recount a particular incident from your service, which may or may not have been funny at the time, but still makes you laugh?

SSgt. Humeston was marching our platoon across the grinder, and the band was practicing near the Iwo statue. I was squad leader, third squad, and I knew that he was at the rear of the platoon, and he couldn’t see me glance toward the music. I still had my eyeballs focused in that direction when I heard Hummeston running toward the front of the platoon. I still remember thinking . . . oh boy, somebody is about to catch it.

All of a sudden, he was marching along at my left shoulder, his right hand clamped down hard on the back of my neck and his left hand strangling my throat. HOLY CRAP. I couldn’t breathe, and I sure couldn’t answer his questions about what the hell I’d been staring at, and was I queer, and was that why I was watching my queer friends tooting their horns and playing their drums, and did I want to sleep with them, is that it? Do you have a boyfriend in the band?

It seemed as if his stranglehold lasted an hour. When we got back to the squad bay, the guys in the squads marching along behind mine were laughing their butts off. They had seen my head slowing turning toward the music (though I hadn’t realized it), and they knew Hummeston was going after me. Of course, by then, with all the teasing and joking I was getting there in the squad bay, I could see how funny it was. That was the only time a DI laid a hand on me during my time on the Island.

What profession did you follow after your military service, and what are you doing now? If you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

How many field days does a Marine participate in? Dozens? Hundreds? It seems as if we spend half our enlistment cleaning the squad bay or compartment.

So, what career did I end up in? I started working for a janitorial company that was owned by a former Marine. Then I worked at the University of Florida, in charge of the cleaning crews for the dormitories. From there, I transferred to the Teaching Hospital, a 500-bed facility. Over a long career, I have worked in large medical facilities and Omni Hotels, always responsible for the cleanliness. I sort of made a career out of taking over at a facility that was dirty and unsanitary, then turning it into a place people were proud of. I often applied the concept of “small unit integrity.”

Sort of like having a fire-team leader in charge of others. One person was selected for their ability to handle responsibility, and I would work with them and train them to lead others. Most of the time, it worked. When it didn’t, I would reassign the person to some assignment where they could regain their self-respect and maybe again become a team-leader. One thing that never changed: You look after your troops, and they will look after you.

It was amazing how many times I met other managers of housekeeping departments who had been in the Corps or the Navy.

What military associations are you a member of, if any? What specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

The seven-day-a-week nature of my work never allowed time for participation in organizations. Often I had a day shift, evening shift, and graveyard shift to worry about.

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

So many times in my civilian life, I would be confronted with a situation and would find myself silently asking, “Now, how would [fill in the name] handle this?” There was seldom a problem that I didn’t try to solve without relating it to my experience and training in the Corps.

What have I missed about the Marine Corps? Well, you have to remember it has been sixty-one years since I left Camp LeJeune, but . . .

Major Duncan would say, “What I miss most is the smell of 782 gear, and rifle oil, and Kiwi shoe polish, and cordite, and the fragrant urinal cakes that rise up when you walk into the head at the slop chute, and the clip-clop of shower shoes when some guy goes for a shower after lights out. The metallic taste of warm water from a canteen and the “John Wayne” soda crackers from the C-Rations, and an extra scoop of S-O-S on the tray at Sunday chow. The rattle of automatic weapons, the thump of mortars, the pounding of seventy-five boondockers striking the deck as one when the person counting cadence is as precise as the field music’s bugle at morning colors. I miss the sea-lawyers, the chow-hounds, and Gunny seated at the end of the pay-table collecting for whatever charity needs contributions if you’re expecting to be issued a liberty card.”

Those are the things Major H. Gene Duncan would tell you, but Taps have already sounded for him, and he’s leaning near to recite that poem he loved so well: “Now in India’s sunny clime where I used to spend my time, “serving of Her Majesty the Queen . . . ” Then, when he finished the last verse, he might ask, “Did I ever tell you about the time I was leaving Korea, hanging from the bomb bay door at 20,000 feet, and the general demanded to see my ID card and leave papers?”

The older I have become, the more I realize the truth—once a Marine, always a Marine. Colonel Jim Bathurst wrote a book titled, “We Will All Die As Marines,” words that carry the same true message and a book every Marine should read.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Marine Corps?

Pay attention to your training. Push yourself to the head of the pack. Study hard. Learn from the veterans. Here’s an example:

In 1957, I was still an E3 the first time it seemed we might be heading into a shooting conflict, and I had a million questions. After the crisis faded, I sat down and wrote a letter to the Sgt.Major of the Marine Corps. I told him of my recent situation and how it created in me a desire to know much more than I knew about being a leader. I gave him several hypothetical combat situations and asked his opinion about what I should do if I were ever confronted by similar dilemmas. A couple of weeks went by, and one day a reply came—on letterhead stationery from the Sgt. Major, United States Marine Corps, Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, DC.

WOW!. I couldn’t wait to read his wisdom. I tore open the envelope and there it was THE LESSON. Here is what the Sgt. Major of the Marine Corps wrote to me:

Dear Corporal Rousseau, [in ’57 an E3 was a Corporal]

In reply to your question, every situation depends on the situation and the terrain.

Sincerely,

(his name), Sgt.Major, United States Marine Corps.

WHAT? WAS HE KIDDING ME?

I couldn’t believe it. Fourteen words? I wrote to my friend SSgt. H. Gene Duncan and told him. Duncan wrote back and said the Sgt. Major had honored me with the greatest advice a Marine could ever be offered. And he was right. All my life, I have met life’s problems by first ascertaining the situation and the terrain and then applying the most effective remedy and resources at my disposal.

If you can learn to do this early in your Marine Corps training, you will position yourself ahead of others’ great majority.

PS: I don’t recall the name of the Sgt. Major of the Marine Corps wrote to me, but he was the first to serve in that newly created position in the Corps.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with.

Life has shown us the truth that Once A Marine, Always A Marine is true. TogetherWeServed serves as a reminder of the truth in the statement.

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

0 Comments