PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

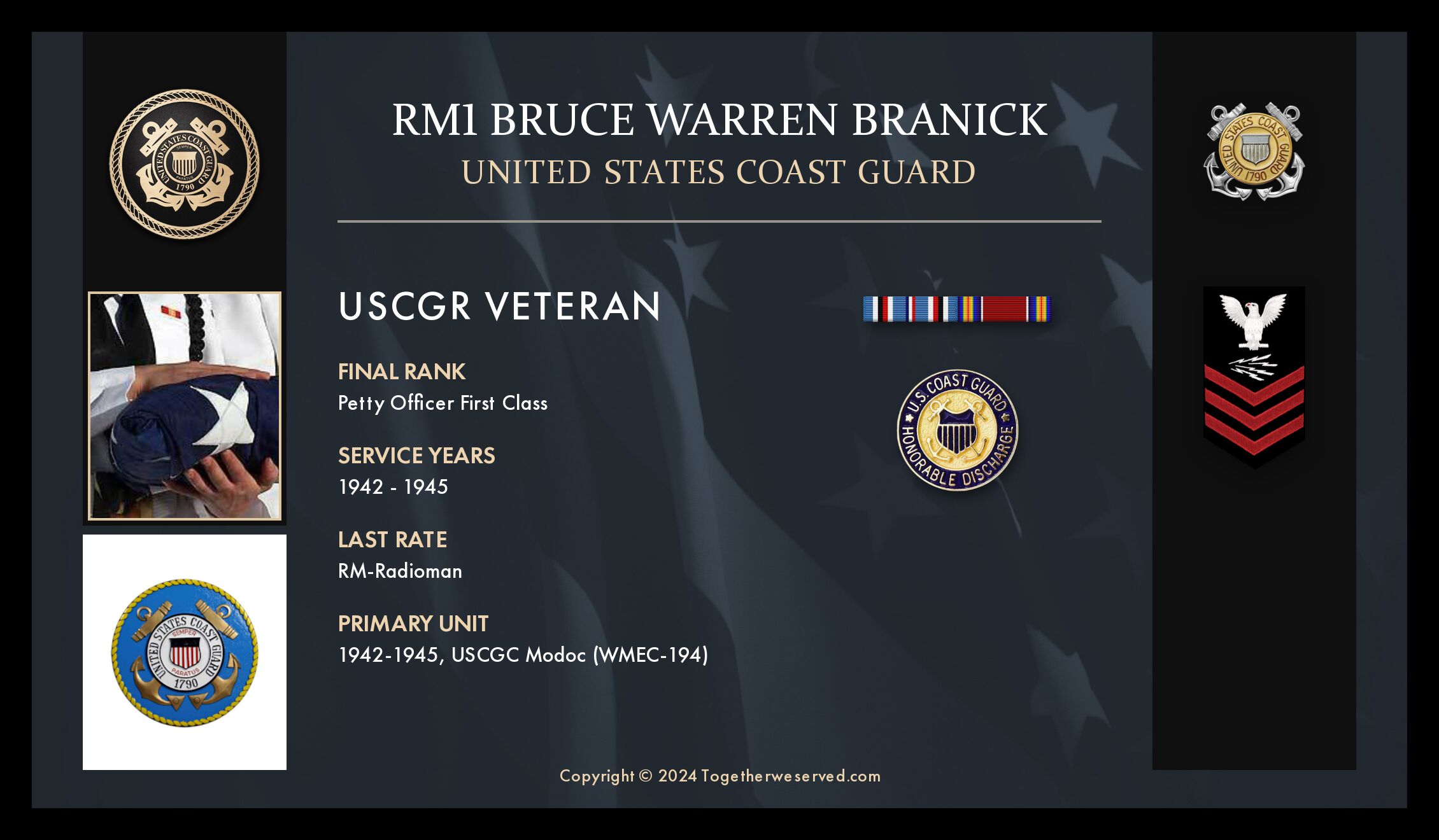

The following Reflections represents RM1 Bruce Warren Branick’s legacy of his military service from 1942 to 1945. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Coast Guard.

My stepfather was a mining engineer and shift-foreman at Ray Mines, Arizona. They appeared to need a timber-helper underground. I got the job and worked in tunnels and adits some 400 feet beneath Ray for over a year. In 1941, as a tool dresser in the Candle House, I resigned to try for radio school at Port Arthur College in Port Arthur, Texas.

In 1937, there were still no jobs in America. Back home, in western North Dakota, my aunt, with some political clout (grown men were still out of work), got me a billet in the CCC, Civilian Conservation Corps, and I was packed up, like a turkey, and trucked to Ekalaka and Boyes, Montana, with two other turkeys.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

Hitchhiking and riding boxcars to Port Arthur, PA, the college president, Mr. Monroe, told me I would not be able to enter classes because the Army’s Signal Corps had taken over the school. My heart dropped into my shoes, and after more trains, planes, and buses, heading eastward, I teamed up with another kid my age in a small Louisiana village. We shared a couple of slices of bread he had purchased.

A troop train sitting sentient along a siding had just returned from hauling “doggies” (1942 soldiers) to the West Coast and was now returning to Camp Beauregard, near Alexandria, LA, for more warm bodies allocated to the Far East.

There was not a soul in sight, and my friend and I boarded the Pullman car with some apprehension. It was warm, and we each grabbed a flat, Naugahyde-topped bench and were asleep in minutes. An hour later, we were thundering eastward and still had not seen a soul.

Looking out dark windows, we crossed various bridges, newly protected by military guard posts and heated by open 55-gallon drums of wood and coal fires, surrounded by freezing soldiers warming their hands and munching food. My companion and I had not eaten for two days; I would later learn I had lost 25 pounds in three days of total fasting on the trip from Arizona. Stiff from jouncing aboard Southern Pacific’s Pullman, my friend and I debarked in New Orleans and went our separate ways.

I got a quick job in a Gulf Oil station at Canal and Claiborne. Temperatures had dropped, and a freeze was imminent. Dozens of cars were coming into the Gulf station for alcohol additions to radiator fluid, and it appeared, from all the activity, that New Orleans was on the cusp of awakening from the Great Depression’s torpor. With my first wages, I stopped at the Holsum Cafeteria and got two eggs, toast, bacon, coffee, and grits—35 cents. I thought the grits were cream of wheat. But no, grits were ground corn, and I have fallen in love with that great stuff that supports the culinary South.

The Army’s uniforms we wore in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) were of too recent memory for a sign-up in that military group. A Navy recruiter told me I needed my parents’ signature in order to join, but my parents were now at another mine, in Bolivia. Friends I was rooming with suggested I would like the Coast Guard.

On a Monday, I got a ride to Coast Guard headquarters, in New Orleans, was signed up, and sent to the Coast Guard Station on Lake Pontchartrain’s shoreline, where I waited interminably for the new radio class to start.

It was mostly small craft of various sizes, for example, the hundred-foot yacht belonging to an American millionaire, loaned to the Coast Guard for training and for the duration of the war. We also boarded merchant vessels docked in New Orleans to familiarize ourselves; one of them was a French dry cargo vessel impounded by the government for the duration. We also studied knots and close order drill and spent a day aboard a Higgins Boat, manufactured in New Orleans—one of those 50 mph rockets driven by huge gasoline-guzzling engines, and with .50 caliber guns accompanied by torpedoes that would soon be launched against Japanese warships.

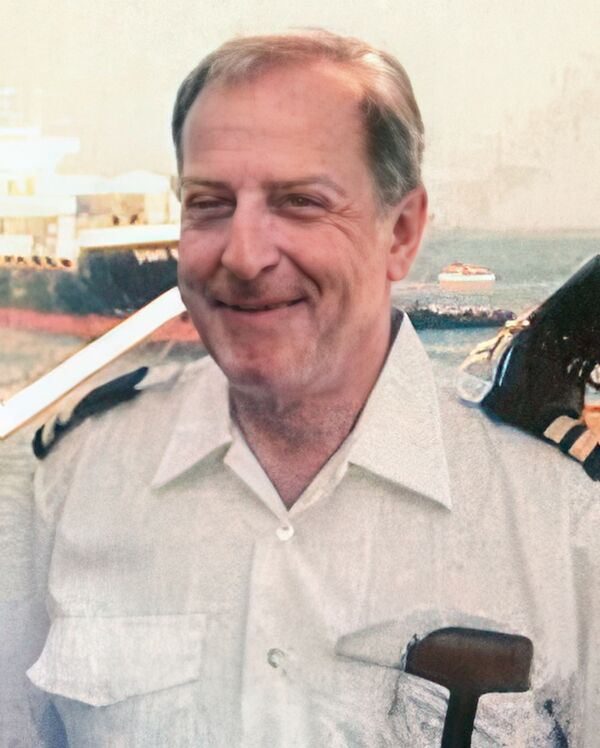

I stayed in the Merchant Marine for almost 50 years before retiring in 1991. During that period, the ships I sailed—tankers, dry cargo, and passenger vessels—traveled all over the world, including four years aboard a Navy tanker, USNS MAUMEE, making December voyages to our Navy base at McMurdo, Antarctica.

During that time, I was married, with a wife and five children, and during those years, I paid a lot of income and associated taxes to city, state, and federal governments. I stand indebted to our European forefathers whose genius and their U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights laid the foundations that made America the greatest country the world has ever known.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

The only assignment I had was on the MODOC. Since it was a vessel, I enjoyed always being on the go. We had to be hitting top speed, 16 knots via straining diesel, before dropping a can, because at a slower speed the stern might be blown off. The cans did make a satisfying roar when they exploded at their settings two to three hundred feet or more below, a large swimming pool’s volume of water and dead fish spewing skyward, like Old Faithful in Yellowstone. We dropped many cans and spent hundreds of nerve-wracking hours at general quarters during my three-year-lifetime aboard the Moe, in the North Atlantic.

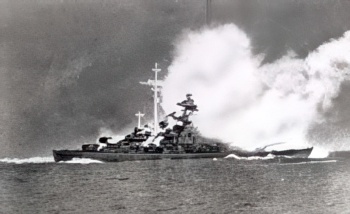

Named after that Indian tribe, the MODOC had a unique operation in 1941 and was involved in the sinking of the German battleship BISMARCK, south of Iceland. The Brits thought MODOC might have been a German helpmate and were considering sinking her, but a British aircraft flew over the MOE and warned her that they were about to be shelled. MODOC departed the scene at flank speed.

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect on to this day.

At the end of our stay near Ivigtut’s fjord, Greenland, we observed 150 American planes en route to Shannon, Ireland, or Britain, piloted by American men and women who helped win the Battle of Britain. They landed on the two-mile-long tongue of a flattened glacier. That night, they were lined up in rows; when we awakened the following morning, they were all gone.

After two more schools, U.S. Navy ASW (anti-submarine warfare school) on Peak’s Island, Portland, ME, I went to another radio school at Atlantic City, NJ, was put in charge of 10 sailors and two Spars, and sent to U.S. Naval Air Station, Richmond, FL, a blimp base southwest of Miami. It later became a CIA base during Kennedy’s aborted war with Cuba.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

Last year, I attended a Coast Guard Change of Watch, where two Captains were elevated, at Beaumont, Texas, and I had a nice conversation with C.G. Admiral Cooke. When you arrive at 95 years, you just naturally accrue a certain relevance, though I have not discovered what that signal quality might be, other than the fact that one made it to old age, on the highway to senility, without losing one’s marbles, and even that is debatable.

Radio classmates who already knew Morse code were so proud; we were snatched out of class about a month into our schooling, leaving the dolts in Baltimore, and sent to the buoy tender ILEX, where we held for ten days before being sent aboard the MODOC, a 240-footer with one 5-inch gun and one 3-inch gun, and lots of cans sitting in K and Y guns on the fantail.

Being good as a Morse Code Operator was my greatest achievement during my service.

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

The World War II Victory Medal, since we were so glad to end such a horrible conflict that millions of lives were already lost over evil dictators.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

Many recruits lived in New Orleans and in the vicinity, and a buddy invited me home for Christmas dinner, for which I was most grateful. Somewhat later, we attended the Comus Ball, saw a couple of movie stars from one of Mickey Rooney’s and Andy Hardy’s pictures. The main part of 1942’s Mardi Gras Carnival was scrubbed because of the Pearl Harbor attack. America was at war, and I waited impatiently for radio school.

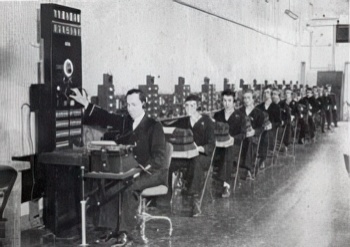

The Coast Guard’s radio school was at the “Yard”, in a suburb of Baltimore, a half-hour bus ride from the city’s center. At the yard, Chief Radioman Dillon greeted us each morning in the brick building devoted to radio scholars: “Rise and shine, sailors! Let go of your —‘s and grab your socks! Let’s go!” We still hated to get up, but the radio classroom awaited us—a huge room with dozens of radio operators at desks, listening to International Morse Code.

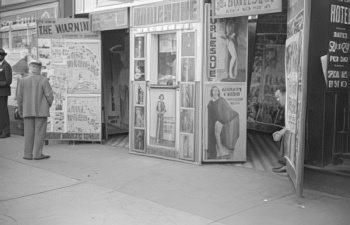

We were off watch on weekends, roamed Baltimore’s streets, watched coochie shows, and looked for young ladies. This was real work, not like today. Women were protective of their innocence, and most of them would rather fight to the death before they relinquished their incredible essence.

One cooch show, as the story goes, finds the manager of a burlesque theater on South Baltimore Street catching a young boy stumbling out of the show. “Heyyyy kid, what the hell are you doing in my show? How did you get in?” “My mother told me if I watched anything bad, I would turn to stone… and it’s already started.”

Having a buddy in the military makes you aware of how good it is to have someone watching your back in life.

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

Gene Gorczyca was a good friend of mine on the MODOC. He always had something funny to share with us. Once I left the service I lost contact with him.

Can you recount a particular incident from your service, which may or may not have been funny at the time, but still makes you laugh?

An amusing occurrence during a blizzard in 1944 involved Gene Gorczyca, 2nd Class RM, and me, a 3rd Class RM, copying FOX (NSS’s 7/24/365 Navy transmissions). Gene was attempting to get a message off to Navy, Norfolk, without success, due to snow static, a complete cessation of signals. He had tried all frequencies from 16 kcs to 22 mcs, without success. “NSS, NSS, NSS;” no reply… “GLD, GLD, GLD” (Land’s End Radio, Britain); no reply.

Gene suddenly burst out laughing, listening to DAN, German Nazi Radio, calling Modoc’s encrypted call sign that changed every 24 hours, perhaps NZRK.

DAN: “Say, Old Man, I’ll be happy to QSP (free relay) your message to Virginia.” Gene thanked him kindly, and then GLD (involved in this signals put-down by the German, for not answering up, to MODOC) tardily broke in and accepted our message; we enjoyed a hearty laugh at the Kraut’s sense of humor.

What profession did you follow after your military service, and what are you doing now? If you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

I stayed in the Merchant Marine for almost 50 years, before retiring in 1991. During that period, the ships I sailed—tankers, dry cargo, and passenger vessels—traveled all over the world, including four years aboard a Navy tanker, USNS MAUMEE, with December voyages to our Navy base at McMurdo, Antarctica.

During that time, I was married, with a wife and five children, and during those years, I paid a lot of income and associated taxes to city, state, and federal governments. I stand indebted to our European forefathers whose genius and their U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights laid the foundations that made America the greatest country the world has ever known.

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

Serving in the Coast Guard helped me be very successful in my later career in the Merchant Marines. The military gives you a sense of direction in life.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Coast Guard?

Be proud of your country and serving. I don’t see young people today wanting to serve this great country as we had done.

Be proud of what you do and do it well.

Learn your job and remember you are protecting those who cannot defend themselves.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with?

I have written a book named MEMOIRS OF A LOOSE CANNON, which reveals more of Modoc’s ventures in WWII, and most e-books sell for a discount at Amazon-Kindle e-books. Most of my buddies or anyone I may have known have passed away. At 95, all I wish for is my legacy to be left behind here on TWS and in my book.

KC 9.30.24

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

0 Comments