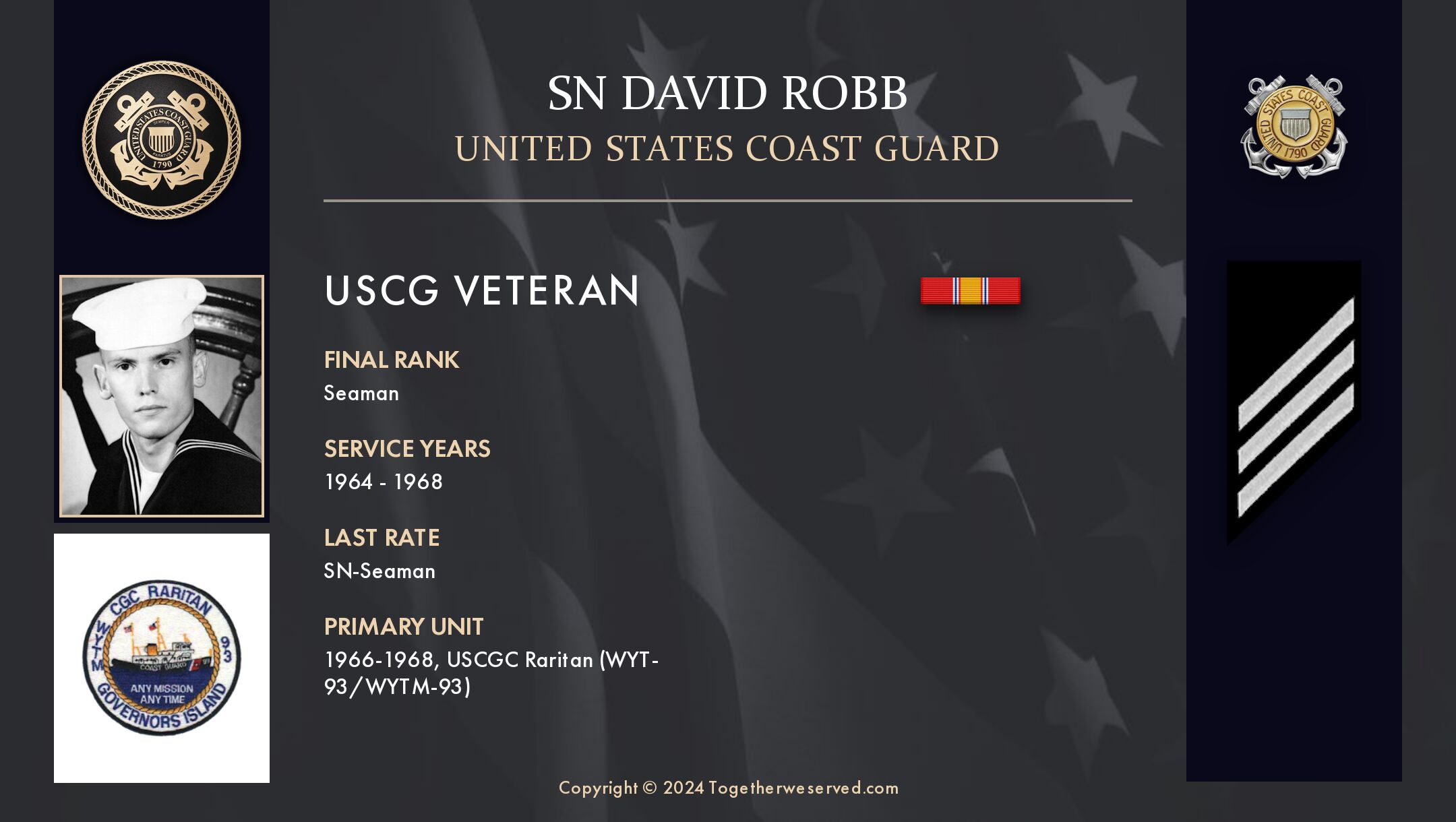

PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

The following Reflections represents SN David Robb’s legacy of his military service from 1964 to 1968. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Coast Guard.

My family wanted me to follow in professional tracks as an attorney, and I realized I was too physical for that kind of life. On advice from my college counselor, he suggested I take a couple of years off to “find myself.” I did. I went to the local recruiting office in Minneapolis, MN, and arrived a little after 1200 hours. All five branches were represented. Army and Marines were at lunch. I was looking for the Navy, and they were out, too.

At the end was the Coast Guard office. As I stood there wondering what to do next. When a tall B1 in perfectly tailored whites with bell bottoms came out and asked me who I was looking for. I said, “The Navy.” He asked, “Why the Navy?” I said, “I like the water.” He asked, “Let me ask you a question. Do you want to take lives or save them?” I was flummoxed but answered, “Save them.” He said, “Right this way.” A few weeks later, I had passed my tests and physical but was underweight. The Bosun sent me to the cigar stand, where I ate bananas and drank water until I gained the 1 1/2 pounds I was short of 118. I was sworn in on October 11th, and my life changed forever.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

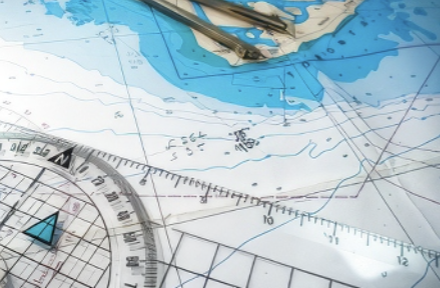

I decided early on that I wanted to be a Quartermaster because I found the charting and navigation aspects intriguing. I also wanted to be up where I could see where we were going.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

Ice Breaking and SAR.

I loved being at sea,and hated being tied to the dock. Regularly took others’ watches rather than go on liberty. The ice fascinated me, and I took pride in a technique that worked well when I was on the wheel. Even though our crew racks were in the bo, I slept like a baby. Kind of like sleeping on a big city snow plow and 25 mph. Lots of noise and shaking.

Liked the rough weather and adventure of Search and Rescue. Lots of bad weather because helo ops had not been perfected in lousy weather. We always went out – no matter what. I logged about 1400 hours in some nasty stuff all over Green Bay, Lake Michigan, Soo Saint Marie, Whitefish Bay – Lake Superior, and the northern half of Lake Huron. We did some 52-degree rolls and buried the bow in green water many times. Too young to be scared.

Learned to control panic when in desperate situations. That helped later in life when I got my Shipmasters’ ticket for all Great Lakes and Western Rivers, Towing and Sail.

My experience with towing the construction barge in the summer was enormous. Slinging a barge from a long tow onto the hip is child’s play now.

Did you encounter any situation during your military service when you believed there was a possibility you might not survive? If so, please describe what happened and what was the outcome.

65-68 was early Viet Nam as you know, and they had not sorted things out yet over there. We got guys back from Nam as sort of a halfway house – like when we got reservists in the summer.

I don’t know if you have ever seen Lake Superior, but it is not like any of the other Great Lakes. We used to break ice up in the Soo. The problem was usually that all the whitefish Bay ice would be jammed down the “funnel” that led to the locks by the prevailing Spring winds. Ore boats would get jammed into the locks as soon as the doors would open, so we would back down to their bows in the lock and power out the 13th step to give them an ice-free track. When we were done, we would go up into Whitefish Bay to about where the Fitz was lying and wait for the next call.

The so-called ocean Coasties would get their first look at this lake, and I always remember their comments: GOD! If you have never been on it or seen it, it is hard to describe it: menacing, cold, mean, angry, threatening, all of it. I spent my summers on it as a kid and felt the same way when I was very young. You can’t feel it until you are out on it. When a sailor first seas it, a chill goes down his spine, and a deep sense of dread stabs his heart. Ocean sailors never joke about us freshwater sailors after that. It got to the point where we would all be quiet as we came around the turn to reveal the big lake before us to hear the reaction of the new guy. Never failed.

Part of my technique in ice was to kick over the wheel for 1 1/2 turns, 2 seconds before we hit the hard ice. This threw a list into the ship before she could turn and commenced her list –

usually to starboard because I’m right-handed. She’d hit the ice at about 8-10 degrees, continue to list right and then react by rolling port. By then, I was spinning the wheel in a blur to get the rudder over by the time she maxed her roll that way to kick her back the other way. I usually got a full 4 1/2 rolls (starboard -port-starboard-port-1/2 starboard) out of her that way.

Did you ever work with any other ships when you were working the soft ice? We worked with Sundew and Mesquite and used a “ski” method. You probably know about it.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

Plumb Island was probably the most enjoyable. It was a lifeboat and a lighthouse station. We did one day on the water, one day at the station, and one day at the light. It was peaceful, and there were long periods of solitude available on that isolated station that was 5/8 x 3/4 of a mile in size. Nine months there resolved a lot in my life.

The problem was that I didn’t fit in well and didn’t know much. I screwed up most of my assignments. (Think Chevy Chase movies)

After my first season there, Group Commander Hutchison advised that he was transferring me to YTM Raritan W-93 because he thought I needed some sea duty. He was absolutely right. Thank you, Commander.

Raritan was not so enjoyable because I didn’t fit well as a loner, but I got along. I can honestly say that I have used everything I learned on Raritan except big ship handling in my later career as a ship’s Captain. After about 1 1/2 years aboard, I had learned enough to become valuable as a Leading Seaman, but crew relationships were always challenging. I was a team player but never joined the team, just different backgrounds. No fights or real problems. Most guys were good, but I was naturally a loner.

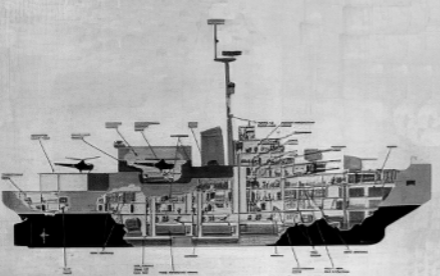

OPERATION OIL CAN

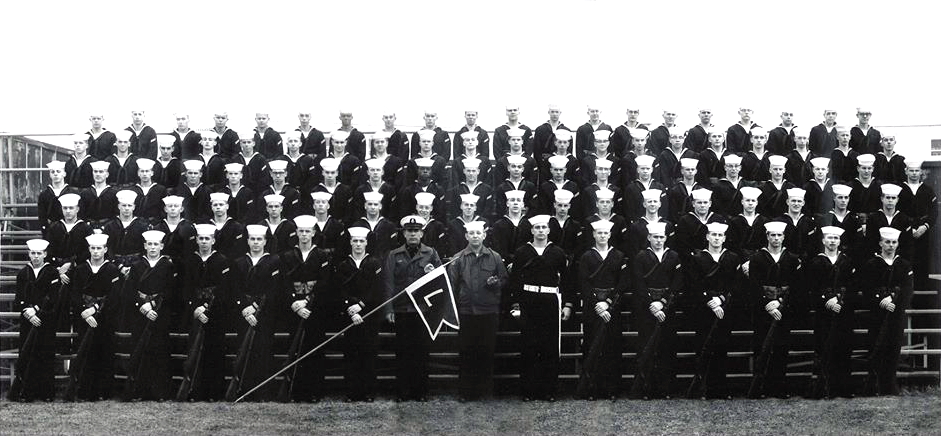

In the ’60s, pocket icebreakers classified as WYTM’s (Coast Guard W Yard Tug Medium Class) served faithfully in their missions on the Great Lakes to keep vital ports and shipping lanes open for commerce and safety, 12 months of the year. For this typical crew of all enlisted men, life was a contrast of beauty, harshness, pleasure, and misery wrapped in a graceful but powerful steel envelope known as the Cutter Raritan. Join the author, an “ex-Coastie,” in the winter of 1966 for a composite cruise of many such sorties that kept this ship and others like it busy for nearly 2,000 hours a year.

I chose the Holiday Inn overlooking Cleveland’s expansive lakefront on this business trip. It was a hot June day in 1980 when I clicked open the door to my room and looked forward to a cool shower and a relaxing walk along the shore to discover what kinds of ships were in port.

Throwing my suitcase on the king-size bed, I pulled open the curtains to reveal the harbor’s panorama before me. It was similar to my home port of Milwaukee, with the modern Coast Guard station on the left, a long break wall stretching from left to right, and hundreds of small boats nestled in a marina down front. The street next to my hotel extended itself onto a pier where an Army Corps of Engineers tugboat was moored in front of another larger tug — a tug with a black hull, white superstructure, and tan funnel.

It was very similar to my old ship; in fact, could it possibly be ??

I squinted to see what was written on her bridge dodger, but it was partially blocked by the tug in front of her. I made out the letters “? ITAN.” It couldn’t be. Is someone playing a joke on me? The Kaw, our old sister ship, was stationed in Cleveland, last I heard. The longer I stared, the more convinced I became.

Stripping off my jacket and tie, I skipped the shower and bolted out the door toward the pier. A man in dungarees sat on her rail amidship with his back to me. A ring of keys on his belt confirmed he was the OOD (officer of the day).

After introductions, he cordially invited me aboard. On the mess deck were some crew members watching T and. I was curious about what had changed. Indeed, nothing much. They had a newer TV with a remote, so they didn’t have to crank the channels by hand as we used to, and there was a new coffee maker; but otherwise, time stood still.

They agreed I didn’t need an escort, so off I went on my own. I climbed two ladders to the bridge and cleared the open hatch. Time had stopped here, too. The color, the smell, and the equipment were all the same. I stepped to the big destroyer wheel where I had spent hundreds of hours and slowly clasped it in my hands.

She lurched. It was as if she knew I was back and bridled. I thought we had been bumped, but no other ship was nearby. Standing there alone, I believe the old girl recognized me. Weird. I gazed around. The engine enunciators were to port and starboard as I recalled the distinct “ding-ding” that rang when the Captain moved them from one speed to another.

The chart table behind me looked the same. I remembered so many nights we held on for dear life as we slogged through horrible gales and seas. I began recalling detailed events and people’s names as if I had never left. I remembered the first day I reported aboard, and then a cavalcade of memories washed over me. They were augmented by distinct visions of the crew as if I had flashed back in time.

The Captain was Chief Warrant Officer James W. Pierce. Chief Boatswain’s Mate Sheldon was our executive officer; Chief Boatswain’s Mate Six was our deck division officer; Chief Engineman Bretthauer was in charge of all things engineering. Quartermaster 1st Class Jess was in charge of navigation, and complementing him in engineering was 1st Class Engineman Mohowski below decks. Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class (Robby) Robinson was in charge of the deck force; Electrician’s Mate 2nd Class Manicke was responsible for the electrical side of the ship. Engineman 3rd Class Korf rounded out the non-com engineering ranks, while 2nd Class Quartermaster Augustin was my senior on the bridge.

I recalled two other men who worked below decks, an E-2 by the name of Yaeger and another E-2 by the name of McMullen. A local boy by the name of Meineke had recently made boatswain’s mate third class when I came aboard and was just learning the job.

I remembered the time the Captain asked Meineke if he’d completed two jobs, to which Meineke replied that he hadn’t because both had to be done at the same time. The Captain asked sarcastically, “Can’t you do two things at once, sailor?”

Meineke replied confidently, “Of course, sir, but I can only do one of them right.”

The Captain chuckled and moved on with no reply.

We had a black cook who was very good but whose name escaped me. In addition to me, there were several other seamen named Gilbert and Vredevoogt, and Arvis. Who were those other guys? Were there any others, or were they just part of the endless change of personnel that reported aboard and then were eventually transferred? To think of all the years that had passed since I had stood at the helm.

I was an E-2 who joined the ship in January 1966 after a year of isolated duty at Plum Island Lifeboat Station and Lighthouse in northern Wisconsin. In ’67, I became the leading Seaman, sort of a Radar O’Reilly of the ship. Because I didn’t advance in rate (although I was striking Quartermaster), I became uniquely familiar with most operations except the engineering department. I scraped, painted, cleaned, performed marlin spike skills, wheeled the ship, shot bearings, worked the radios, and filled in for men on leave.

I thought about the summer of ’68 when we had our annual inspection by the 9th Coast Guard District admiral. He spent the day observing our proficiency through drills. Toward the end, he inquired why I seemed to be working in so many different departments. The Skipper humorously introduced me to the Admiral as “Robb, SN, YN, BM, QM, CS.” He meant that as a nondescript Seaman, I had accepted not only my Seamanship duties but also those of the ship’s office (yeoman), substitute for the third class boatswain’s mate when he was on leave (BM), the third class quartermaster when he was on leave (QM), and the cook when he went on leave for the holidays (CS). I have always appreciated the compliment.

Mind you, I was not a one-man band holding the ship together. I simply had been aboard longer than anyone and became the go-to guy for many things. As anyone who served aboard the YTM’s knew, it was relatively informal as long as the job got done safely, efficiently, and professionally.

I recalled that the controlling authority for our missions was under the command at Group Two Rivers, Wis. Underway; situation reports were relay-radioed to them through other stations. In turn, the group command informed the district of our status, actions, and positions. At the time, Lt. Cmdr. Hutchinson was in charge of Group Two Rivers.

Now, the bridge was steady and silent, but that was not always the way I knew it. Events and conversations rolled in detail like a flickering movie reel before me.

A freshening Lake Michigan gale blasted over the frozen Milwaukee harbor and seared my cheeks to a cherry red. As I trudged determinedly past darkened warehouses in the numbing February cold, I turtled deeper beneath the upturned collar of my heavy wool pea coat.

The nine blocks I had to walk seemed impossible in the stilting cold, but I had no choice. Being on Bravo 2 Standby status, I had less than one hour to be at my assigned billet aboard the ship before we got underway. Too many times, after I had ordered a good meal or a new movie rolled, I would spot the usher or waitress searching me out — a clear indication that we were going again.

Would it be for a day, a week, or a month? I never knew, and there was never time to call and let people know of the interruption. I simply would not be able to be there. I felt that I was being rude, but such was the nature of my winter duty for three of my four years in the US Coast Guard.

About the time that I thought I would collapse from exposure, I rounded the last building. Bathed in the glow of her amber deck lights, my ship surged gently at her moorings while her stack rapped a staccato that echoed off the grain elevators across the river.

The 110-foot USCGC Raritan WYTM93 was moored at the unglamorous foot of Broadway Street in the Milwaukee River. Snuggled next to a grubby old brick warehouse and but one swing bridge from the open sea, she was at home in her noble but hard-working, blue-collar environment. Stout, vigorous and powerful, she was no different than any other commercial tugs of her class, except she was an icebreaker — and a good one at that.

Underwater, her 5/8-inch, armor-plated steel hull concealed a large notch in her forefoot with 9 tons of concrete that helped her punch through a solid foot of rock-hard ice. In her generous belly were two husky GM 8-567 diesel engines that generated megawatts of electricity to a massive 1,000-horsepower General Electric DC motor. This, in turn, cranked an unforgiving three-bladed steel prop 9 feet in diameter that would keep her thrashing Neptune’s margaritas at 5 knots all day long.

The brass handle clattered as I heaved open the heavy-weather door amidships. A steamy concoction of diesel fumes and freshly brewed coffee tingled the frost from my numb face. Stepping over the high sill, I locked out the stinging cold and greeted our claustrophobic galley with its glaring fluorescent lights, satin stainless steel cabinets, and inclined terrazzo deck in exhaled victory.

Through my thawing toes, I felt the vibration of the big engines rumbling their warm-up. The cramped mess deck to the right was deserted, but the voices of the returned crew could be heard in all parts as 12 highly trained and professional men prepared the ship for sea. Having ducked below to the crew’s quarters, I changed quickly into the uniform of the day as 2nd Class Boatswain’s Mate Robinson called out, “Hey, Robb?”

“Yeah, Boats!”

“You’ve got Mooring Station 3 for getting underway, and then you’ll have the midwatch with the Old Man.”

“Got it, Boats. What’s going on?”

“We gotta break a tanker into Muskegon, Michigan,” he shouted back and hurried on. I never liked the “mid,” and I liked the four to eights even less. My biological clock insisted that I sleep then –, but I knew better than to complain.

Grabbing my leather gloves and my olive-green, fleece-lined work jacket with the high collar, I headed for the starboard quarter to man my mooring station. My boondocker work boots held the heat from the ship, and the jacket kept out the buffeting gale, but cold stung my legs through the lightweight denim pants.

Up on the bridge, I knew the routine well. The special sea detail would be getting everything ready. The Papa flag was hoisted at the starboard spreader, indicating recall for all hands. The radar was whirring away, the radios crackled on several frequencies, and charts were taped to a green Formica navigation table with a bold pencil line stretching east for 80 miles across Lake Michigan. A large silver clip held the most recent MAFOR weather report above the chart on the padded light green bulkhead next to the old Hallicrafters radio direction finder. On my watch, I would be lee helmsman.

A screeching whistle from the direction of the bridge yielded the silhouette of Robby, giving us the signal to single up all lines. Easier said than done. The temperature had dropped to nearly zero after a recent wet snow, and now the heavy Manila lines were frozen stiff. A fellow crew member hopped ashore and lifted one of the two heavy warps over the massive black bollard on the wharf as I struggled to get it aboard before it flopped in the water. A couple of full turns and a loose half-hitch around the horn was all that held us close. Our lines were started aboard, so a man needn’t make a perilous leap to a slippery deck when we cast off.

Through the frosty glare of a deck light, I saw our 2nd Class EMT Manicke unscrew the telephone line from its boxed connector on the side of the superstructure and stow it carefully ashore. This confirmed that we were definitely going. A moment later, the tall, slender silhouette of Capt. Pierce stepped to the bridge wing in his khaki uniform, nylon arctic jacket, and tan officer’s cap that was no less than jaunty. He had two hats — one was crisp as new for going ashore, while the other was his more comfortable “steaming” hat that had tinges of green on the gold emblem from his years of ocean duty.

The noise of the ship precluded any spoken commands, so hand signals were required. He pointed to the appropriate mooring station, twirled his pointing finger around, and snapped his thumb up to indicate that we should cast off smartly. Starting with Station 4 at the stern, he then pointed to 2 near the bow, then 3 near the quarter, and finally, 1 at the bow that we swung on to get headed in the right direction.

Worked perfectly every time.

We had a clever cable setup with a quick-release Pelican hook that held us to the wharf as we pivoted the ship 180 degrees in the narrow river channel. A single blast of the ship’s whistle prompted the retaining ring to be hammered back, thus freeing Raritan of her shackle. Three more short blasts and the eerie circa-1920s bascule railroad bridge before us clanged with bells and red lights. This was attended by a mournful grinding and creaking as it began its ponderous 90-degree swing.

Like the groaning of an old man getting out of a chair, I could almost hear it grunt as it began its laborious rotation. Atop the girdered trestle sat a dingy clapboard-sided shack and a silhouetted figure of a man I never met who waved a concerned “farewell” as we accelerated past.

At the union of the Kinnikinnick and Milwaukee rivers, we again sounded a single short blast to announce our entrance into merging traffic and came left at 4 knots to stream the inner breakwater walls toward the deserted harbor. It was not by mistake that the Army Corps of Engineers laid this course to be exactly 090-270 degrees, as it provided a quick accuracy check of the backup magnetic compass. Breasting the harbor, the corroborating engine room bells clanged as I visualized the Skipper clasping the non-military Schlitz Beer tap handles of the enunciators firmly and moving them from Step 3 to Step 5. Crossing the darkened harbor, the ship increased her heave and scend that was the harbinger of the weather “outside.”

All eyes scanned to port. The wind tore away billows of steam in a long line from the tall gray smokestack of the city’s water filtration complex nestled on the north side of the harbor. As the wind increased, steam would back-wind down its side and indicate the force and component out on the lake. We learned quickly that an optical inch of back wind meant rough weather. Tonight, we were stunned as the steam crept down its leeward side a full 2 inches. It was going to be worse than bad. Like the little girl with the curl, when Lake Michigan was good, she was very, very good. But when she was bad, she was very, very bad. Tonight’s trip promised to be awful.

Leaving the smooth haven of the protected harbor, Raritan dove into a terrifying maelstrom of the open sea. Six- to 8-foot seas driven by 35-mph northeast winds bashed the 20-foot-thick concrete break wall with huge vertical geysers along its 2-mile length. Enormous waves and craters rebounded with the next phalanx of inbound curls, creating a chaotic mess of cresting waves and monstrous troughs. Those not on watches skedaddled to the refuge of the warm mess deck and grabbed anything secure.

The moment Raritan crossed the line from the harbor to sea, she pitched into a monstrous trough with a thunderous crash. Our stomachs floated to our chests as the deck dropped from beneath our feet. Then, it was rammed back into our gut as the ship hit the bottom of the trough. With our bow impaled in the black comber, the ship rolled 40 degrees to starboard as we felt the vibration of the ship’s propeller slapping the surface. Wallowing dangerously to port and back, she struggled to regain her buoyancy and then ponderously clawed her way up the next mountainous wave.

Raritan crested as a kid gasping for air in a cold pond and exploded over the top in a shower of icy spray. Unsupported for half her length, she tripped like a breaching whale with a thunderous splash that buried her bow to her gleaming white superstructure. With her foredeck submerged under solid green water, only the tiny jack staff at the bow showed above the churning sea. Again, she rolled to starboard and bobbed up as tons of Lake Michigan coursed down her decks and sluiced through her freeing ports.

Defiantly, she raised her head again and smashed into the next deep trough. We exhaled after a half-dozen frightening dives, satisfied that she was going to be all right, albeit rough. Robby hushed, “Jeezes, I hate it when she does that. She takes so damn long to come up.”

“Nobody told me I had been assigned to submarine duty,” someone wised.

The rest of the crew was seated at the mess deck table or standing with a firm grip on anything secure. With the weather doors dogged and a minimum of good ventilation, all waited for the first effects of the weather on their stomachs. Some of the off-watch crew hit their bunks while the others waited on the mess deck where they could be close to the head if and when the need arose to throw up.

Three hours later, McMullen approached my rack, jiggled my foot, and said it was time to take the watch. The deck and bulkhead were dangerously confused as I timed a perilous jump from my second-level bunk to the deck. A slight miscalculation would fling me into another set of steel racks with bone-snapping results. Hand over hand was the order as I probed my way through the red-lit darkness to the careening ladder up that alternated between horizontal and vertical.

My trusty Accutron said 11:50 p.m. With one hand to hold and one to make coffee, I barely got to the bridge in time to beat the eight striking bells of the bridge chronometer. Western Ocean Watches (arriving late) were never tolerated.

On the bridge, I timed the rolls to open the heavy lee door and slipped inside before its weight crushed my sleepy 120-pound body. Working around to the far side of the seesawing chart table, I checked the course and track line that was laid out by the previous watch. The phosphorous green radar screen was clear except for some sea clutter in the center that was normal in bad weather. The departing lee helmsman advised that the regularly scheduled car ferry would probably cross below our track in an hour.

Satisfied that I was brought up to date, I maneuvered quickly to the Captain and received permission to relieve the watch. It happened seconds before we both were thrown across the bridge. Moving next to the helmsman, he advised our course was 078 degrees true and “nothing to the right.”

I repeated, “Nothing right of 078 true. I relieve you,” and grabbed the wheel. Whenever I had the wheel, I never got seasick because I could anticipate the ride, like riding a galloping horse vs. getting flung around behind it in a carriage. I was part of the horse.

Already, my stomach was producing acid, as was everyone else’s. Wedged snugly between the starboard enunciator and the big curved windows, Capt. Pierce rode the bridge securely, yet I knew that his gut was hurting like mine.

“Helmsman: Come right and steady up on course 075 degrees true. Jess. Note the log: Raritan C/C (changed course) at 0007 hours to ease the ride and compensate for wind and sea set. Speed: 8 mph — mostly vertical, just kidding. Wind NNE at 35, seas 8 feet. En route to Amoco Sinclair to assist in icebreaking ops and escort to Muskegon, Michigan. ETA: 1025Z (4:25 a.m.).”

At the wheel, I replied, “Steady on course 075 degrees true, aye — sort of ?” as I fought to hold my footing and course at the same time. The bulkhead often became the deck and vice versa. 075 degrees was a target. I was lucky to hold her within 5 degrees either side of that, so I had to average it and make sure that the average fell more to the left than the right.

“Very well,” the Skipper replied as he struggled to study the chart, contain his stomach and hang on with all of his strength. The ship rocked 45 degrees each side of up and pitched violently with every wave. The combination resulted in a dizzying confusion that even caused the magnetic compass to spin out of control. Thank God for the Sperry Gyro-Compass that was more stable. The most difficult part was keeping our feet in touch with the deck.

“Aye-aye, Cap’n,” Jess was finally able to reply as he turned to 3rd Class Quartermaster Augustin, who heard the command and was already writing with one hand while desperately clutching the heaving chart table edge with the other.

Raritan continued her labored, sickening, oscillating hobby-horse easting across a tumultuous Lake Michigan. The Captain noted that she wallowed in the troughs. Moving the enunciator handle forward, another step returned the satisfying bite of Raritan’s big propeller as she punched through the boarding graybeards.

Outboard, the sea was a cacophony of menacing white swirls amongst the roiling troughs and breaking crests. The wind rose past 40 mph as Raritan regularly exposed a third of her keel atop each crest, then smashed into another trough as her prop thrashed air and water. This caused a violent shaking and chatter at intervals of 12 to 15 seconds. Raritan’s antics that night probably qualified us for a bronco riding championship.

Outside, it was black. We could see nothing ahead, but to port and starboard, our bow wave was illuminated by our running lights to a sickening reddish or greenish black. Reflections of the glistening gunnels told us we were making deadly ice.

Jess noted, “We can try heaving-to and knock a lot of it off with wood mallets.” Raritan surfed off another 15-foot crest and buried her bow from sight with a thunderous crash. The Captain mumbled a worried, “Yeah, and lose a couple of guys in the process,” as he strained to keep from being thrown forward.

Fortunately, I had heeded the Captain’s advice earlier. Stick to carbohydrates whenever bad weather up. That meant no drinking, either. But now it was the coffee working on us. We just had to have our cup of joe. My stomach was on fire, and my head pounded to the throbbing engines that vibrated and rattled everything that wasn’t bolted down. The air became foul and clammy from lack of circulation and heat. Augustin kept his face buried in the radar’s black rubber light shield for vessel traffic that the weather might obscure, though it was unlikely at this time of year. But he knew the Grand Trunk car ferry would be coming soon, and we didn’t want to meet it.

“Maybe we can call the ferry and see if the weather is any better on the east side of the lake,” Pierce suggested as Raritan bashed into another trough and rolled deeply on her side.

Jess was jammed between the port side enunciator and the windows, but he held tight. He gauged the threatening green seas that boarded and rolled aft down the main deck.

And so it continued. Raritan slogged and thrashed defiantly through the howling gale. It was punishing to hang on while keeping the logs up to date, rotating wheel watches, radioing position reports, and plotting our DR’s (dead reckon positions).

The slamming and jolting fatigued everyone quickly. After two hours, my stomach muscles felt as if they had been doing hours of push-ups. My knees ached and threatened to buckle. Forearms and shoulders knotted from strain, and everyone’s feet throbbed. Nausea and stomach acid combined with sweats that flashed from hot to cold. The radical rolling, pitching, and yawing made us as dizzy as the compass in search of north.

With the fatigue came weariness, and with weariness came the potential for errors in judgment — something that couldn’t be allowed in dangerous seas. Our fatigue grew worse with every passing hour, but we had to press on.

Unable to sleep, Cookie made it heroically to the bridge with a tray of black coffee in hopes of stimulating the crew. He didn’t stay, preferring his warm galley below, and soon escaped through the sheltered lee door. Two wave troughs later, the coffee had sloshed on the freshly painted bulkheads and streamed across the once spotless linoleum gray deck.

Three agonizing hours later, Chief Brett and his perennial Clark Gable grin struggled through the heavy door as though he were arriving at a party. This wasn’t it, but his grin was a pickup to an otherwise foreboding bridge.

“Hey, Chief! Welcome to the party. C’mon in and grab something!” Capt. Pierce artificially cheered.

“Hey, thanks! Where’s Tricksie?” he quipped, then carefully worked himself in behind the gyro repeater, facing the helmsman with his back to the breaking seas. Capt. Pierce razzed the chief. “What’s the matter? You don’t appreciate our lovely view?”

Brett gazed casually over his shoulder with a disgusted wince. “Christ! There’s nothing out there I want to see. I don’t know why you guys think it’s so great up here. It’s barely moving in the engine room. It’s like an upside-down pendulum up here. You guys are swinging worse than my old tomcat’s tail.”

“I agree, Chief, but the folks back in Washington kind of frown on us officer types driving around when we can’t see where we’re going, don’t’ cha know,” the Skipper retorted in his Southern accent as he forced some bile back down his burning throat. Focusing on business, he continued, “By the way, how’s everything in the engine room?”

“Oh … we’re all right,” Brett replied wearily as he bobbled back and forth like a counterweighted doggie in a car’s rear window. “Yeager’s not looking too good, though. He and Mohowski went out last night and had a couple of beers across the street. They didn’t follow your 24-hour suggestion when the weather got bad. All this rocking and rolling has them looking pretty green,” he said with a broadening smile.

“Couldn’t happen to a nicer pair of guys!” Jess joked as the rest of the bridge joined in a chuckle that was quickly followed by a groan as Raritan buried her bow again. This time, she hung an extra moment, freezing the conversation. A stab of fear sliced through the bridge as she listed steeply to port, vibrated, and then heaved herself back over on her starboard side until most of the water shipped aft and raised her bow. Then she regained her rhythm and slammed steeply back to port. The angle indicator over the helmsman flopped between 45 degrees each side of straight up.

Groaning from the strain, Jess asked Brett warily, “Ughah! Isn’t this tub supposed to roll all the way over after 52 degrees?”

Brett gave a pained smile and said, “Actually, it’s a lot more than that because we replaced the old steel main mast a couple of years ago with a new aluminum one that reduced her vertical center of gravity. Don’t worry. She probably wouldn’t go over much before, ohhhhh … say, fifty-FOUR degrees now,” and gave him an eyebrows-up smile.

“Oh! That’s real reassuring,” Jess groused as the inclinometer hit 50 degrees on the next dive.

Shaking off his gloom, the Captain asked, “Hey, Brett. I hear you’re talking about retirement. That true? Where the hell would you go?”

“Well, humph,” Brett mulled as he considered the subject. “Some days, I wonder. Ya know, I’ve been doing this for nearly 25 years now, and about 20 of them have been on sea duty. Katie’s used to having the place to herself, so I’d probably just be underfoot most of the time,” he modestly exaggerated. Then again, there are trips like this, and I think, ‘What the hell is an old man like me doing out here, anyway?’ Jeezes, Skipper, I got more time drinking coffee than most of these guys have in the service,” gesturing around the bridge.

“Hell, I don’t know … right now? I think I’d go aft, steal one of those pretty ash oars out of the lifeboat, and put it over my shoulder.” His grin broadened as the punch line welled up in him. “Then, I’d start walking west until someone asked me what that thing over my shoulder was, and that’s when I’d know I’d arrived,” he ended with a broad “gotcha” smile. The audacity of the chief copping the oldest line in the service brought a good belly laugh.

Having surreptitiously gauged the danger level of the ship under the guise of a social call, Brett worked his way around the heaving bridge to the leeward door, saying, “Hey, you guys. This is for the birds. I’m going back where it’s saner.” Then, looking at the Captain seriously, he asked quietly, “Ah, you say this old tanker is broke down in the ice or just waiting?”

Matching his mood, Jack replied, “Just waiting. She’s pretty thin-skinned, so she didn’t want to chance it.”

“Smart. What’s the ice like there?”

“We don’t know yet. Those guys wouldn’t know how to give a proper ice report if we asked.”

“Yeah. Then I’d better get the guys ready to clean the sea chests. When we get in that stuff that is all broken up from the wind, it clogs the water intakes, and the engines overheat. They got’ta get in there with their bare hands and clear the slush out. God, you’d think there was a better way if you’re going to be an icebreaker,” Brett humorously griped.

Shaking his head in amazement, Capt. Pierce replied, “See ya, Chief,” as Brett negotiated his way into the maelstrom.

The bridge returned to its silent routine as the four of us endured the violently bucking tug silently across the vicious black sea, each lost in our own thoughts and anxieties, struggling to perform the duties of the watch and battling the relentless lurching and slamming that threatened to maim us.

Below decks, the abandoned galley was filled with the sounds of crashing dishes. The seal on a forward port leaked a trail of water down the bulkheads and across the deck. The nauseating smell of vomit from the nearby crews head permeated the damp, stagnant compartment. Several moaned in their sleep as they slumped on the deck, exhausted.

With the engine room placed below the waterline, the rolling was moderate, but the heaving made movement around the exposed engines dangerous. The off-watch snipes had managed to wedge themselves securely into pockets between machinery and frames and slept. The two watchstanders moved carefully, hand over hand, amongst the screaming diesels. It was suffocatingly hot and smelly, and the roar of the big engines was deafening. All communication was by sign language.

In the forward berthing compartment, most of the crew was wedged in their bunks spread-eagled with their elbows stabbed between the double side rails to keep from being thrown out. Sleeping was like riding a fast elevator that fell and rose 10 stories at a time over and over. Often, there was daylight between a man’s body and his bunk. It was punishing but the best of the alternatives.

On this trip, no one escaped seasickness. It was as bad as it ever got. Seaman Arvis lay in his top bunk writhing in dry heaves, promising anybody a month’s paycheck if they could get the “Old Man” to stop the ship for 15 minutes. Seaman Gilbert, youngest of the deck force, lay semiconscious in the crew’s head with his face next to the shower drain, having vomited for three hours. For the last hour, he moaned unmercifully with the dry heaves and dehydration.

Capt. Pierce, who appeared weakened from the ordeal, managed to hold the wheel periodically when everyone else was out the lee door depositing their stomach contents to the wind. He later admitted that not only was he tired, but he fought the fatigue that threatened his judgment. Only by concentrating on the working of the ship and mentally inventorying the status and condition of each department did he manage to stay alert.

After seven and a half hours of dizzy yawing and pounding, the crew was pretty well wiped out. We measured our misery against the slowly ticking hands of the numerous brass ship’s chronometers found throughout the ship. As we drew nearer the ice field, we relished the prospect of the restorative, calm, flat water that lay in its lee.

Finally, Augustin reported a radar target in a large ice field a point (11 degrees) off the port bow. Capt. Pierce raised his binoculars and picked out the twinkling deck lights of a small tanker surrounded by boulders of white ice. Her wheelhouse was mounted on the stern of her cigar-shaped hull, and she appeared to be riding comfortably.

The Skipper pulled back from his glasses for a moment, re-sighted, and asked, “How far away?”

“Slightly over five miles, Cap’n,” Augustin replied wearily without pulling his head out of the radar shield.

“Damn small ship,” muttered Pierce as he looked again at her profile. Raritan was sailing eastward, and the Amoco Sinclair’s bow was facing northeast, so he was eyeing her from her port quarter, which made her appear smaller. He mused that maybe it was part optical illusion, but she seemed to be sitting awfully low in the water. In fact, she was the last of a fleet of old whalebacks that were designed to ride 7/8 submerged. From a distance, only her superstructure was visible.

“Robb. Let’s work our way around the southeast side of that field and get us out of this mess. I’ve had enough,” the Skipper ordered.

“Aye-aye, sir,” I said as I tripped the wheel right to bear on the south end of the ice field that glowed in the otherwise pitch blackness.

The Skipper added, “Jess, make an entry in the log, ‘0447, note our position and add, sighted target Amoco Sinclair hove-to in ice field at five miles. Altering course to V/C/S (various courses and speeds) to position us in the lee of a large ice field. Hoving-to until daybreak per standard ice ops and performing morning cleanups. Then, contact Coast Guard Station Muskegon and ask them to relay comms for us to the group. Send our current SITREP and weather on scene.'”

“Aye, Captain. Do you really want the men to do morning cleanups after what they have been through?” Jess asked carefully.

“Those that can. Let the others get some recovery time. Once we are in the lee, some of them will come around. The place must be a glory hole down there. We can’t operate like that.”

As if we had sailed onto Walden Pond, the wild water ceased, and we cruised on a placid sea protected by the big ice field. The wind continued to howl, but we rode on a sea of glass.

The next watch reported to the bridge, looking like they had gone five rounds with Sonny Liston. Chief Six, Boatswain’s Mate Robinson, and two others staggered through the change of watch routine. All I could think of was getting into my rack. As we headed out, the Skipper stopped us. “Robb? Augustin? You guys look pretty good. How about getting things a little squared away before chow? Wake Cookie and get him going at 0500. Thanks.”

So much for my rack time. The new crew on the bridge would only stand a two-hour watch because the four-to-eights were always “dogged” to allow for duty rotation. It didn’t seem fair, but it had to be done. We started by mopping the mess deck with a bucket of steaming soogee water and rinsed it with a straight stream of hot water from a garden hose. It all ran down the corner scuppers. After dry-mopping the leftover puddles, we did the same to the galley and then woke the cook while Augustin made a fresh pot of coffee. The invigorating aroma renewed my energy, but then I did have three hours of sleep before going on watch — and that is what the Captain was probably thinking. It was interesting how I could feel on the verge of death and then just fine as soon as the ship got into calm water. Imagine going from the 24-hour flu to perfect health in less than a few minutes, and you get the idea. I was even hungry.

Cookie went to work rustling up oatmeal, pancakes, scrambled eggs, bacon (crisp), and some fresh fruit. At 0600, the crew staggered on deck and eventually had a full breakfast. even Arvis. Gilbert still had a sensitive stomach and stuck to a few swallows of oatmeal with brown sugar for energy. By 0800, we had finished colors, and the forenoon watch was in control of all departments. Augustin and I were given permission to sleep until lunch, which failed due to the noise.

What noise?

Did I neglect to mention that we were an icebreaker and the berthing compartment was in the bow? Once we cleared our breaking plan with the Amoco Sinclair at daylight, we proceeded to bash ourselves relentlessly into a foot of solid ice for the next three hours. To appreciate the effect on my sleep, strap yourself on top of your local snowplow next winter and try taking a nap. It is exactly the same. Back and forth, back and forth, foot by foot, hour after hour. My rack was bolted to one of the ship’s main web frames that was nearly a foot wide. It would flex as much as 2 inches every time we hit the ice. I struggled not to bounce out, but I must have dozed off for a minute because I remember being awakened again for my watch.

Cookie had prepared spaghetti and meatballs, but only half the crew showed up. I wolfed down a few bites, poured more coffee, and headed to the bridge to stand the same watch I did 12 hours before.

We ceased breaking for a minute to rotate the crews and went at it again. A glance out the rear ports revealed that we had made only 100 yards all morning. At this rate, it would take days to get us in. In the meantime, the residents of Muskegon would be getting pretty chilly without a resupply of heating oil.

In the mid-1960s, an oil pipeline had not yet been laid along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. All heating oil was brought in by ship. It was efficient and inexpensive but a problem in the winter months. That’s where we came in. If a tanker could not make it into the shallow harbors along that shore, it would require a YTM with only 13 feet of draft and a lot of punch. That’s where the name “Operation Oil Can” came from. Over on Lake Huron, it was called “Coal Shovel,” where our sister ships did the same thing.

The direct method of bashing the ice was not getting us very far. We routinely tossed a red coffee can over the rail at the bow to mark our progress. Arriving on the bridge, we could see the can clearly astern of us. A few tries by the Captain yielded little more progress. Not a man to waste time with vanity, he turned to Jess and asked, “You and Robb think you can get us there any sooner?”

Jess looked at me as I smelled glory. As a team, we had done this successfully before and developed a secret technique. He replied, “Yes, sir. No problem.”

“Jess. You have the conn,” as they traded places at the enunciators.

“OK, Robb. Let’s take her back a little extra. Keep your rudder straight as we back down. I don’t want that old tanker towing us home,” Jess admonished.

We slid back about 100 yards and came to a full stop. With a confirming nod, Jess dropped the enunciators one bell at a time until we were at Step 9 and at full speed of 13 mph. A mustache bow wave spread broad on either side of us as the hard edge of the field approached rapidly.

“Stand by for impact,” Jess alerted.

I got ready. The timing was everything. We heard a few bumps and scrapes as we pushed through some debris ice, and then came the hard edge. Just before we hit, Jess dropped the handle from 9th step to the all-powerful 11th. When we hit, there was an explosion of crystal ice shards that fanned 40 feet over the bow and created a rainbow from the breaking sun behind us.

On cue, I spun the big destroyer wheel as hard as I could to port. Raritan yawed left and rolled her 360 tons on her side as a huge crack zigzagged away off our port bow. As soon as I felt her list approaching 15 degrees, I reversed the wheel by grabbing a spoke low on the wheel and pulled with all my might. The wheel spun to a blur as I heard the power steering unit groan mightily. Raritan obliged the sudden shift of thrust and lay over on her opposite side. Another crack grew as the ship shuddered under the strain. The theory was to spread the weight of the ship’s hull over a greater area of the ice than would normally be if we just hit it head-on.

Feeling our progress diminish, I centered the rudder as Jess retracted the enunciators and prepared to repeat the process. We had made nearly 50 yards, and now the cracks relieved the pressure on the hull. A sense of victory overwhelmed me as I studied the retreating ice pack. Dressed in my dungarees, a chambray shirt, a wool sweater, and a CPO jacket, I was pretty well insulated from the cold that swept through the open bridge door we kept for ventilation.

We halted our retreat, and then, as if to whip a horse to a gallop, the stern dropped as the whole ship lurched forward under the massive thrust of the big prop as Jess carefully dropped the enunciators again to Step 9. As we charged the ice again, we heard the random collisions of vagrant ice floes in our path. That was followed by the “shushhhh” of the hull surfing into our recently created slush that preceded the pack. A moment later, the enunciator bells rang as Jess dropped the throttles to the 11th step.

Just before the stem cracked the ice shelf and rose high over the edge, I laid her over again. From the bridge, I could see spider-web cracks appear in the ice and, then, 30-foot plates slowly upended themselves to disappear beneath the surface as we plunged forward.

Again, I spun the wheel to our maximum rudder angle and then back as Raritan waddled and crushed the ice under her. When our progress ceased, as it eventually did, I centered the rudder, and Jess repeated the whole process. Fifteen minutes later, with several more successful hits behind us, I was down to a T-shirt, bare arms, and sweating with the bridge doors open and the outside temperature around 16 above zero.

By mid-afternoon, the Amoco Sinclair fell astern of us in our slush-filled track as we eventually bucked our way past the harbor entrance lights. Once inside, we continued our track another three-quarters of a mile up the inner channel to Lake Muskegon. In the spirit of a victory lap, we cut several figure-eights in the thinner ice to make the going easier for the old whaleback. Soon, the tanker was nestled in her berth at the Standard Oil docks and discharging her cargo of vital heating oil into the near-empty storage tanks ashore.

It had taken our entire watch to get us in, and I was tired, really tired. The Captain conned us to the Huron Cement Co.’s unused dock, where we secured for the night as the local Coast Guard station took our radio watch. Cookie served pork chops, mashed potatoes, and green beans.

Before the Captain had finished his meal, Robby rapped on the bulkhead above the wardroom. “Enter!” came the sharp reply.

Robby stepped carefully down the ladder to join Chief Six, Bretthauer, and Sheldon all reclining around a table that held the remnants of another good meal. “Yes, Robby. What is it?” the Skipper queried wearily.

“The crew was wondering if you were going to grant liberty to the off-watches,” he asked politely.

“Liberty! Why, I thought you guys would want to stay aboard and get some rack time tonight,” as he scanned the table with mirth.

“Well, you know the motto of the Coast Guard, sir,” Robby chided.

“Yes. Semper Paratus, Always Ready?” he nodded knowingly.

“Well, sir. We are definitely that, but I was referring to, ‘We have to go out, but we don’t have to come back,'” he wised with a toothy grin.

“My, my. I have never had such a heroic and dedicated crew. (Chuckles all around). Make sure everything is squared away before you leave. Liberty expires at 0600 tomorrow,” he advised.

“Thank you, sir,” Robby acknowledged and retraced his steps topside. A moment later, there was a spontaneous cheer and the sound of heavy boots scurrying to get ready. Liberty was granted at 1800 hours. Never much of a party animal, I opted to take another man’s eight to twelve “trick” so he could go. The next morning, it was reported that those who went ashore couldn’t pay for a drink at any bar. The local press had made a big deal about the oil shortage, and we were seen as heroes coming to their rescue. The people were appreciative, as they always were in the many towns along that side of the lake, which I am told continues to this day. We had fulfilled our destiny once again in the great rescue traditions of the Coast Guard, and it felt, indeed, satisfying.

The next morning, we performed cleanups, chow, and colors did some routine administrative maintenance, and got back underway for home at about 1000 hours.

The weather moderated with the sun and a backing wind that knocked down the rough seas of the day before. The gentle swell was enough to make working out of the question. Those not sleeping played hearts on the mess deck table, watched TV, wrote letters, or read.

One of the nicest places on the ship for me was aft. In the summer, we rigged a big awning to shield us from the sun’s blaze. In the winter, the overhanging shelter of the superstructure between the freezer and P50 portable fire pump was out of the wind and quite pleasant in weather above 25 degrees and sunny. Plunking myself down in a big coiled hawser, I gazed at our foamy wake and the swooping gulls dancing above our stern. For peace, comfort, and simple pleasure, there wasn’t a cruise ship in the world that was more luxurious for me.

Eventually, a couple of guys joined me with mugs of hot coffee, and the gabfest was on. This time, we made our maximum speed of 13 mph, so our 80-mile return was eaten up in just over six hours. just in time for our precious liberty.

I decided to try catching the newest James Bond movie again. Having checked out with the OOD, I went over the side with the promise of a relaxing evening. An hour later, in the dark, with my buttered popcorn and soda tucked between my knees, the silhouette of a creeping spy fired three shots from the big screen as a bright flashlight crossed the side of my eye.

“NO! Not again! We just got back!” as I heaved myself out of the red velvet seat. The usher apologized as he led me into the deserted lobby. “Sorry. Your ship just called. It seems that a small airplane went down over Lake Michigan off Waukegan, and they said to tell you that they are getting underway.”

As I turned for the door, he added, “Oh, one other thing: The manager remembered you from the other day when you had to leave early. He said to give you these,” and held out two complimentary tickets. “They’re good for any time.” I thanked him for his kindness and hurried out the door.

An hour later, the silhouette of a man high atop the old trestle bridge who I never met waved his concerned “farewell” as we glided through the frosty darkness again toward the big lake.

We never found the plane. We spent five days sailing ladder and expanding square patterns to ensure we searched every square inch of the probable crash area, but there was no trace.

The sun was getting low when I realized that I had been standing at the big wheel for over an hour, lost in my reverie.

“You OK, Mr. Robb?” asked the OOD, who obviously had been standing behind me for a while.

Startled, I struggled to regain my composure. “Oh! Yeah, Boats. I’m… I’m fine. It’s? been a long trip,” I excused.

“You know,” he went on, “every once in a while, guys like you show up out of nowhere, and later we find them on the bridge here or down in the engine room or aft on the fantail, just staring.”

“Yeah? well?” I mumbled as I looked around for the last time, not finding the words I wanted. “I put a lot of water under her keel. She was a good ship? always brought us home.”

The big boatswain’s mate nodded silently in respect. As we laid to the main deck and then onto the asphalt-coated pier, I gave her one last look. He added as we shook hands, “Don’t worry, Mr. Robb. We take really good care of her. We like coming home, too.”

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect on to this day.

Pistol Range – I barely qualified on an M1 rifle because I was only 120 pounds. The rifle drove me back into the sand just from the recoil in the prone position. Somehow, I made it, or they were just kind. Hit the bull’s eye 6 out of 7 times with the .45 Colt. Fun.

During my third group inspection on Raritan, I was paid the highest compliment of my life in the spring of ’68, about 6 months before I got out. We were billeted for 16 men, but 4 were always on leave, so 12 of us had to fill in as we could. I was a ‘deckie. Because of this arrangement, I was always filling in for a guy on leave. I never had time to complete my course for QM, but I did the job of a QM3 and others. That spring, I was down in the crew berthing,g squaring away the hoses from a fire drill, when the Old Man and the Admiral from Cleveland D9 came down. They chatted as I worked. Then I heard the Admiral ask, “Hey, Jim (Pierce). Who is this guy? Every year I come down here, I see him all over the place?” Captain Pierce W2 invoked his great sense of humor and replied, “Oh, that’s Robb, SN, YN, BM, QM, CS.” They had a good laugh. I was never so proud. I had come a long way from Plumb Island. Because I did not advance, I stayed aboard Raritan for two years and 8 months. I can still walk her decks and remember every hatch, fitting, and rig on her from keel to truck.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

As a leading Seaman, I had a deck crew of 6 guys, all a foot taller than me. I learned a lot about leadership and discretion. We got the jobs done right, and I didn’t have to be a hard ass.

One night after more than several beers, I hit on a girl who apparently belonged to a big Navy Machinist Mate at the local beer bar across the street. The Navy had a reserve DE about a mile from us, so there were both services in there at the same time. I was about to get my head knocked off when my crew came up and suggested the other guy go find someone his own size unless he wanted to take on all 6 of them. It was tense for a moment, and I left with some more wisdom.

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

National Defense. I was proud to serve. I should have had the Good Conduct also but because of a 1st Class Engineman who has since long passed, forgot to tell me that I should wake him at 0530 one morning when I had the 4-6 dog watch. He claims I forgot. I didn’t and wouldn’t. After 2 years of watch standing every third day and more, you don’t forget that kind of stuff. I thought he was a jerk, but my childhood military school training taught me to “never complain and never to explain.” Stand like a man and do your duty. When called before the old man, he asked if I had anything to say. I decided I would not get into an argument in front of the Captain. I was a Seaman, and he was a 1st class. I wasn’t going to win, no matter what. I took a week’s restriction. Our QM1 then told me I would lose my GCM. Had I known, I would have squared off in front of the old man.

So be it. I only had 6 months to go. Later, I heard that he finally made Warrant Officer, but because he was such a jackass with a cruel streak, the Group had to send a few guys to attend his ceremony when he got his bars. Everyone else refused to participate. Much later, I heard he crossed the bar, and only 2 people were there to attend his funeral, and they were just his neighbors. I realize I have been blessed in hindsight, but I still feel sorry for him. If you were in Group Two Rivers around that time, you know who I am talking about.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

When I was at Plumb Island, Wisconsin, in ’65, Our BM2 was a fella name, Theile. Yup. That’s the one. Allen Theile. He later became Master Chief and Chief of the Coast Guard. It didn’t surprise me when I first heard about it. He was very proud of where he came from. I loved how he always said when asked, “Ahm from Algoma, Wisconsin, Slick!” He was a natural-born sailor coming from a family of commercial fishermen from Algoma, north of Sheboygan. He loved his job no matter how bad it got. He felt that every day of his life in the Guard was a gift from God and treated it so. He was good and did everything with a bit of swagger.

One day, when I bragged about a job I completed, his advice was, “Hey, remember, Slick. When you’re good enough to be arrogant, you don’t have to be.” These are words I live by and preach to this day. Even then, he was the essence of what the Coast Guard was. Everyone liked and admired him. He was slow to criticize and quick to teach. When called for my first SAR at 0400, I absently groused about the time of day. Of course, he overheard me as I was tying on my boon dockers.

“Hey, Slick! You know, you have to go out. You don’t have to come back. You volunteered for this. Get your butt moving.” I can’t argue with a man when he’s right. So much of life is voluntary. It was probably that definitive moment when I crossed my charted datum from a boy to a man. I headed to the boat with pride in myself and my service. It was a hell of a trip in the only 41-foot motor lifeboat in the service. Pitch black, mountainous seas, 40 mph winds, and navigation by RPMs by magnetic compass on a course that was strewn with shoals and rocks. He got us there and back. Thanks, ‘Boats.

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

Wow. It was between 54 and 58 years ago that I was in. I’m 79 at this writing in 2022 and in good health. I just renewed my Coast Guard Master’s license for another 5 years with no medical restrictions. Most of those guys are long gone. I have been in contact occasionally and exchanged a Christmas card with Leonard Farr. He was a Fireman (E3) on Plumb Island. He was on that lousy trip I mentioned above with me. We were both sicker than dogs and heaved our guts side by side. We lost track of each other until he contacted me about the old 41-foot Motor Life Boat we were on that night. He found it on the beach, I think, mostly intact. He got it moved near his home for restoration in Massachusetts, where he lives with his wife. I like Leonard. Good man. Everyone else I can think of is gone, I believe. I run into guys that were once on Raritan in my Ship Master’s life, but it is usually long after I was there, so there is a connection but not a tie.

Can you recount a particular incident from your service which may or may not have been funny at the time but still makes you laugh?

Yes. Strange, I should remember this and not others. It exemplifies our Captain’s great sense of humor, Chief Warrant 2 James Pierce.

I am pretty sure it was the Spring of 1967 when we were in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, rafted outboard the 180 ft Buoy Tender Mesquite, who later met her untimely end on the rocky Keewanaw Shoals on a December night in Lake Superior. Often, a 110 YTM and a 180 were assigned ops together for Operation Oil Can in Lake Michigan. We used a “skiing” technique together to open tracks in soft, slush ice.

Because Mesquite’s home port was Sturgeon Bay, she headed back there on completion of ops as we followed for some necessary Charlie status at the shipyard there. Often, our liberty time was pleasantly spent in their company.

With a fresh coat of bottom paint, we headed back to Milwaukee, where Tug Arundel out of Chicago had been covering our ops area for us while we were gone. Mesquite was dispatched several hours after us to relieve the Arundel so she could do her Charlie status. Inevitably, Mesquite caught up to us about 50 miles south of Two Rivers, Wisconsin. Relations between our two ships were very good, but we never passed up a chance for a little friendly but intense competition such as snowshoe (broom) hockey on the ice at 5 above zero in Tee shirts after chow.

Captain Pierce had a witty sense of humor that was aggravated by his strong North Carolina accent. As we were sagging south on a rare calm night and a full moon when spotted Mesquite climbing up our wake on the radar. It became apparent that she was going to pass us close to the port. I don’t know what your definition of “close aboard” is, but mine is NOT less than 10 yards at 15 knots. It was obviously an outlandish display of fine Seamanship and good-natured intimidation; Captain Pierce ordered, “Helmsman, steady as you go,” which I did with white knuckles as he casually radioed the Mesquite himself and drawled: “Ahhhh, Coast Guard Cutter Mesquite. This is the Coast Guard Cutter Raritan on Channel 22. Over.” Mind you; it was a Lieutenant Commander on the other end of that mike that was sliding up our port quarter.

“Coast Guard Cutter Raritan. This is the Mighty Coast Guard Cutter Mesquite. Over.” Rolling eyes and stifled chuckles crossed our bridge. Captain Pierce thought for a moment and keyed the mike, “Most Honorable Coast Guard Cutter Mesquite. This is the Most Humble Coast Guard Cutter Raritan. Would you mind watching your wake as you pass? We just got everything all “set up,” here, don’t ‘cha know.” I held my breath for the long delay that followed, but when Mesquite finally keyed her reply, we could hear her entire bridge crew breaking up in busted laughter. The talker took several tries to acknowledge our polite request through his own uncontrollable laughter and eventually managed a “Rog-ha! Roger!” With renewed pride in our Skipper, we watched Mesquite’s white stern light disappear ahead of us in less than a half hour as we settled back into the cozy darkness of the red light mid-watch and the vibrating thrum of our big 9-foot propeller.

What profession did you follow after your military service, and what are you doing now? If you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

I mustered out in October of ’68 and went to work as a yacht designer for several years in the Great Lakes area working for such notable firms as Palmer Johnson Yachts on the ’72 America’s Cup boat owned by Ted Turner. Then I went to the noted Burger Boat Yard, where I did shop drafting on Ray Croch’s (founder of McDonald’s) 72-foot aluminum power boat. Ray was a prince of a man with no airs. We shared several lunch bags in the carpenter’s shop with stacks of beautiful walnut. I was supposed to take over as manager of the large Milwaukee Marina later in ’73 and moved my board and wife to an apartment overlooking Lake Michigan and the yacht club.

When I showed up for work that fall, Bill Krueger, owner/entrepreneur, said the recession meant I had no job. He offered me a position as a customer service representative in his web printing business for less money but more hours. I stayed for 5 years and was known as the CSR who was working there until he got a real job in the boating business. Yacht design and boating is a feast and famine-business. It’s a long trip between cups of coffee. It was a good laugh to those of us in the know. Thirty-three years later, as Regional VP of Sales for the world’s largest web printer, I had three ulcers, pneumonia, impossible sales goals in a dying industry, and working for, I think, my 7th printing company. I’d had enough. I tried a few short careers in different areas, and then a retired Coast Guard Chief Engineer friend invited me aboard a Navy Sea Cadets training boat in the Chicago Harbor for a ride. They gave me the helm and, after being re-invited several times, suggested I get my CG Ship Master’s ticket. The short splice is I got my ticket and worked out of Chicago for 5 years and then took a delightful job managing and wheeling two 100-foot dinner boats lying at the head of navigation on the Mississippi in Minneapolis.

I became the operations manager while the boss’s sister-in-law ran sales and reservations. I worked there for 10 years. Meanwhile, after an amicable divorce, I met a southern belle from Louisiana. We were married on board the Paradise Lady dinner yacht. The following year, I made a final entry in the log, “All stop. Finished with engines. Anchor down.” We retired near the Tennessee River at Mile Marker 66. My house is on top of a hill, and there is no water in sight, but I can smell it. Close enough. 14,000 hours underway, both fair weather and foul, and now I’m home.

What military associations are you a member of, if any? What specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

The International Association. I represent Lodge 12, Twin Ports, and Duluth Superior.

Let me tell you about one particular annual meeting. I presumed it was a cowboy theme because they always theme every year before. So I dress to the nines for the upcoming meeting; well, this year, they decided there would be no theme. And lo and behold, the other members failed to tell me this. I believe it was on purpose.

So I walked through the doors as the picture shows, only to find everyone in suits. I remained that way the rest of the evening with my dignity preserved, although I wore a sign that said “tourist.”

Just think Hawaiin Insurance Agent. One of the moments that will never be forgotten. It did run through my mind, “I’m gonna hurt these guys.”

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

I feel that I could have had a promising career in the Coast Guard. Looking back, 20 years is not so long. I loved the mission of the service more than the Navy. I got the real hands-on experience that I use to this day. At my age, I looked back for the fork in the road that got me here. What I have seen are many forks and many opportunities. ‘Would’a’ and ‘could’a’ don’t really work for me, nor do I believe in fate. I have a belief that we are here on earth to make the best of what we have with the personality, brain, and muscles we were born with. Experience is the great teacher of wisdom. My life is my life, but there were many places where I could have changed it, but I didn’t. I did what I did because I thought it was the best option for me at the time. I have often felt compelled to do certain things at certain times. Many call it “your gut talking.” Although my Baptist wife will tell you I am not compelled to attend church every week, I feel that the Lord has guided me every step of the way. So many times, things could have turned out worse than they did. I witness that in hindsight. I am grateful for that and the wisdom to listen when spoken to.

Do I miss the Coast Guard? Hard to say. For me, it’s about the water, first and foremost. Always has. Since the age of seven, I have been in boats. I have no preference for power or sail. There is something tranquil in a light canoe on a still lake that compares to nothing else. Close-hulled on a 135-foot-4 masted schooner in a force 5 is one of the most exhilarating things I can imagine. The thrum of a big diesel engine under me the moment before we hit twelve inches of ice is unforgettable. In that order, I’ve owned 5 yachts from 51 feet to 18 feet. The best one was the last, was an 18ft English yawl rigged, open hull Lugger. I sailed her single-handed across Lake Michigan and then lengthwise 300 miles. That was followed by a treacherous crossing of Lake Superior. She served me faithfully. I was able to teach my three boys all they needed to know to start them sailing their own boats on that Lugger. I have no regrets.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Coast Guard?

DO IT – but do it because you love the water. The Coast Guard has changed since I was in. We were Treasury agents with the primary mission of saving lives. Nothing nobler than that. Be clear about your goals and study the Guard’s history. I wish I had known more when I enlisted. It would have helped me focus better.

And remember, whatever you do, don’t laugh the first night you get to Boot Camp unless you really DO like that Bosun who is screaming in your face.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with?

Nothing with TWS but a few weeks ago, I ran into a Coastie at Lowe’s in Paris, TN. A half-hour later, five of us were standing around together telling sea stories. Probably the largest gathering of retired or veteran Coasties in the US at that moment. Great time. About one in three in Tennessee are military vets, and we are known as the Volunteer State.

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

0 Comments