PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

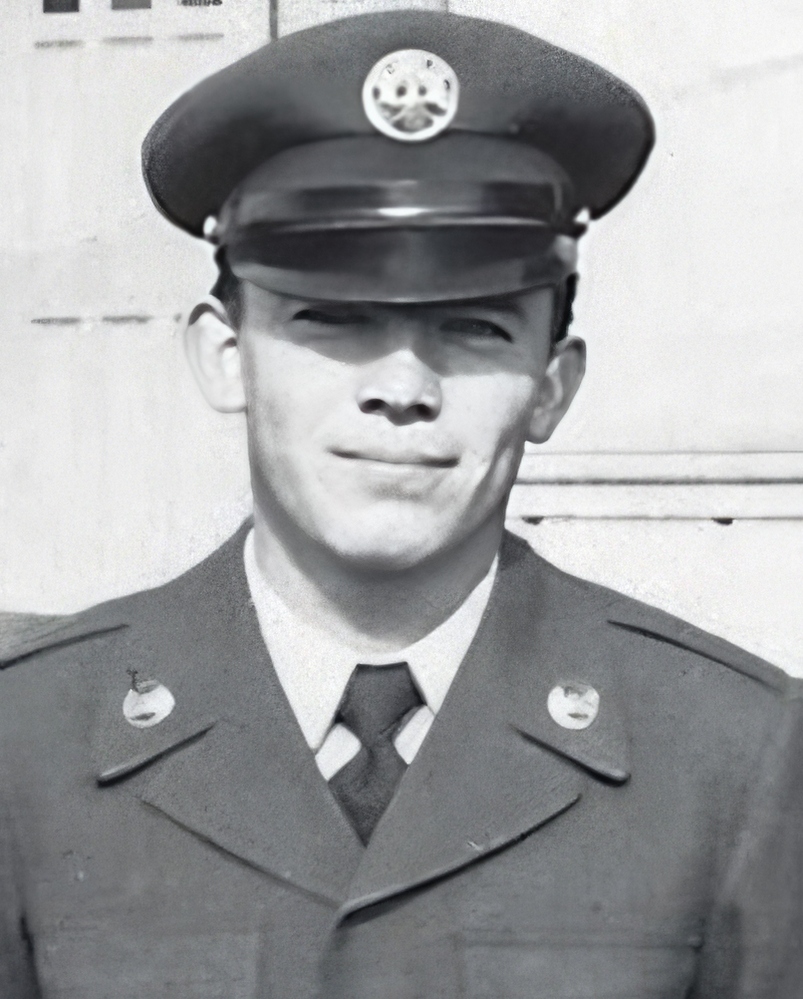

The following Reflections represents SSGT Kenneth Russell’s legacy of his military service from 1951 to 1954. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Air Force.

My draft number was coming up, and I preferred the Air Force over the Army.

The Korean War was on, and it looked like I would be drafted, so I enlisted in the Air Force in Salt Lake City, Utah, in January 1951. My basic training took place at Lackland AFB, Texas, but it was so crowded because of the Korean War build-up that we were living in tents and our civilian clothes due to a shortage of uniforms. So we were shipped out early after only four weeks and were supposed to finish our basic training at our next base. That amounted to a close-order drill twice a week for three weeks. I was assigned to B-29 Turret Mechanic school at Lowrey AFB in Denver, Colorado, for twelve weeks. Near the end of that school, they said there was a shortage of gunners and took the top ten percent of the class for gunnery training. Gunnery school was at Lowrey, also.

Then we returned to Texas to be put on a crew at Randolph AFB, Texas. Our Aircraft Commander was a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS) and had been recalled to duty from his service in World War II. Being a member of the LDS church, I joined his crew, which consisted of a majority of Mormons. We trained there as a crew and soon became one of the top ten crews and were sent to Forbes AFB and Smoky Hill AFB in Kansas for combat crew training. We trained in gunnery, bombing, navigation, and all areas of flying a combat mission.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

I was halfway through college Pre Dental, and I needed to get back to college.

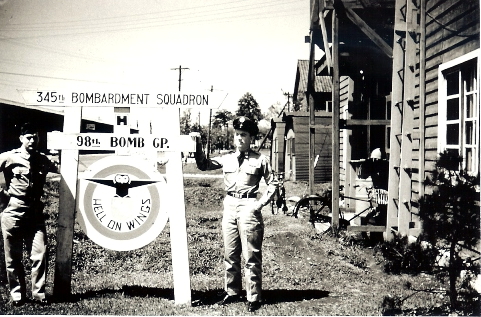

With all of that behind us, we picked up a new B-29 at Travis AFB, California, and flew it over to Japan by way of Hickham AFB, Hawaii, Kwajalein Island, Guam, then to Yokota AFB, Japan, which would be our home base for flying combat missions over North Korea. We were assigned to the 345th bomb Squadron, 98th Bomb Wing; the crew chief took care of all the aircraft maintenance and ensured all four engines were in top condition. Needless to say, this was a vital part of flying any mission. We soon found that Sergeant Snyder was one of the best crew chiefs and gave our crew a lot of confidence in the reliability of our aircraft when we were flying a mission. We flew some training missions to acquaint the team with the bombing method of “SHORAN.” This method of bombing a target involved following a radio arc to the target. It took excellent coordination between the pilot and the radar operator to get the bombs on the target. Visual bombing would only happen on daylight missions when the Bombardier would use the “Norden Bomb Sight” to drop the bombs. We only flew one daylight mission. All the other missions were flown at night to avoid the Russian-built MiG-15 fighter aircraft.

As a crew, we went out to the flight line and watched crews take off for their missions to North Korea. Before we flew a combat mission, we could tell that takeoff would be a frightening experience. As we watched other crews leave, we could see that they were using almost every foot of the 7000-foot runway. The concern about takeoff was that each B-29 had ten tons of bombs on board plus 4,500 gallons of high octane fuel and twelve fifty caliber machine guns with 500 rounds per gun. If you add all this up plus the airplane’s weight, you’re asking seventy tons. {10 tons over max wt] to start flying after a 7000-foot run. Standing on the sidelines watching this take place made us. We trained there as a crew and soon became one of the top ten crews, and we were sent to Forbes AFB and Smoky Hill AFB in Kansas for combat crew training.

We trained in gunnery, bombing, navigation, and all areas of flying a combat mission. After training in Kansas, we were sent to Camp Carson, Colorado, for survival training. We were required to live off the land for two weeks, avoid the aggressor forces behind enemy lines, and then cross a guarded border crossing. It would be an understatement to say survival training in the mountains in February was cold. With all of that behind us, we picked a new B-29 at Travis AFB, California, and flew it over to Japan by way of Hickham AFB, Hawaii, Kwajalein Island, Guam, then to Yokota AFB, Japan, which would be our home base for flying combat missions over North Korea. We were assigned to the 345th Bomb Squadron, 98th Bomb Wing.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

The fuel crew came by and loaded 80 gallons of oil for each engine and 4500 gallons of high-octane fuel in the wing and center tanks. Each crew member had specific things to check and prepare for the upcoming mission. The day of the mission was a little more relaxed. We tried to get a few hours of rest, knowing we would be flying most of the night.

We were usually so heavy with fuel, ammunition, and bombs that it took the entire length of the runway to get off. Even then, we only had a 500 ft altitude two miles out. We were using a Shoran-type night bombing that was very accurate. Gen. W. G. Ganey, FEAF Commander, stated that; “B-29’s using Shoran, could bomb within a 1000 ft circle around any given target”. Missions up to the Yalu River were 12 to 14 hours long, on which we took extra fuel in one of the bomb bays. These missions were close to China and its airfields, which meant there were always many MiGs looking for us. We would take off early in the evening, and during long missions, we would not return until it was just getting light at Yokota.

We carried different bombs and different fuses depending on the target. The bomb would be 2,000 lbs with a thick steel nose and a second delay fuse for dams and cement hydroelectric plants. The bomb fuse would activate as it hit the roof, traveling at over 600 mph, and would explode inside the building. Most often, we would carry forty 500 lb general purpose bombs, less if we were carrying extra fuel in the bomb bay. If the target were a railroad bridge, there would be 2 hr, 4 hr, and 6 hr delay fuses on a few of the bombs that would bury in the mud or dirt, discouraging repairs on the bridge for a time. There would usually be 3 photo flash bombs that would go out last with spoilers on the fins to slow them down so they would air blast to illuminate the target for photographs. At times, one or more bombs would hang up in the bomb bay. One of us would have to go out in the bomb bay to trip the release and drop the bomb. We would fly in a stream of 12 to 15 bombers, 3 minutes apart and atthree3 different altitudes. Planes were 500 ft apart in altitude, so we were 12 min ahead or behind the next plane at our altitude. The altitudes we usually bombed from were from 24,000 to 29,000 ft.

Our crew flew 27 combat missions over North Korea. Because the B-29 was no match for the MiG 15 fighters, our missions were primarily flown at night. North Korea had no night fighters, but they had very accurate radar-controlled flak guns and radar searchlights. They would have MiGs up at night, but they couldn’t see us unless their searchlight locked on us, allowing them to trigger an attack. If the weather was overcast, the searchlights could not penetrate, and the fighter threat was minimal, but the radar flak could operate through the clouds and remain covered. The MiG fighters mostly came from the airfields up in China just across the Yalu River. We had bombed most of the fields in North Korea but were not allowed to attack any of the airfields in China. Because our gun flashes were also visible when we fired, our guns were fitted with flash suppressors, which cut the gun flash down to almost zero. We had an Electronic Counter Measure Operator on board for missions that would be heavily defended. If a radar searchlight locked on to us, he would jam their signal, and the light would swing away. If their flak were accurate, he would jam their signal, but there would still be 3 or 4 shells on the way up. They then would change the frequency and try to lock on our plane again. The most strategic targets were heavily defended, with flak, searchlights, and fighters flying around, trying to find us in the dark. These were the dams along the Yalu River, Pyongyang supply yards, railroad bridges, ammunition factories, and hydroelectric plants. After our bomb drop, we would fly to the nearest coast and out over the sea.

We went to chow in the early afternoon and had a good dinner. (The food was excellent while we were at Yokota A.F.B.) After dinner, the entire crew met at the Squadron Briefing Room with eight other crews to get the low-down as to what our target would be, what the weather would be like en route and over the target, and what we could expect as far as flak and enemy fighters, Our call signs were words like “Shelter 45” or “Tango 1”, “Lefty 48”, “Silver 125”, and so on. Our altitudes were staggered from 30,000 feet for the first airplane over the IP to 31,000 feet for the second airplane, then 32,000 feet for the third, and then the next down 1000 ft. This way, we could keep the enemy flak gunners guessing as to altitude, and we would be 15 minutes ahead or behind the next plane at our altitude for safety. After our briefing, we loaded in a six-by truck, and they hauled us out to our aircraft. Our first duty was to go through a crew lineup in front of the plane for crew inspection. We wore a parachute, life vest, a 45 cal pistol, a survival pack with K rations, water, a solar blanket, and North Korean money. And there were barter trinkets like watches and compasses. Also, we had a one-man raft hooked to our parachute that we sat on. It was hard and had a C02 cartridge on one side that caused a lump. After setting on that for a 10-hour mission, you had “Dingy But.”

Target: Oriental Light Metals Company

I was stationed in Japan as a gunner on a B-29 bomber crew assigned to fly long-range night missions over North Korea. We would fly in a bomber stream at night because the B-29 was no match for the MiGs in the daylight.

On the night of July 30, 1952, we were on a mission to bomb a factory for the Oriental Light Metals Company not far from the Yalu River along the Chinese border. After our briefing, we took off at 1820 hours with 4500 gals of gals, 40 500-pound bombs, and ammo canisters full of 50 cal. ammunition. We were at 70 tons and 10 tons over the maximum payload.

We departed over the Sea of Japan towards North Korea. The target was heavily defended with radar-controlled flak guns and searchlights. As we neared the target, the large Chinese airbase lit up across the river, and the Migs were taking off. We were not allowed to cross over into China. Their flak guns were very accurate and could still operate even in cloudy conditions. They quickly knew our altitude, heading, and airspeed. If their searchlight locked onto our plane, our electronic countermeasures (ECM) operator could jam the signal, and their light would swing away. If the flak was close, the ECM operator could jam it, but with so many signals, he couldn’t jam them all.

At “bombs away,” we put 38 bombs through the factory roof, but two were still hung up in the rear bomb bay. Two flash bombs went out last above the target to provide enough light to acquire photos. Photos taken from the two planes ahead of us showed light damage. However, 90% of the building had been destroyed after our bombardment, and our plane was hit with flak just after our strike.

When we were back over the ocean, we dropped to 8000 feet to depressurize. I went into the open rear bomb bay and released the two bombs. Following our mission, our crew was nominated for the Distinguished Flying Cross for accuracy with a determination to do so with heavy opposition.

Did you encounter a situation during your military service when you believed there was a possibility you might not survive? Please describe what happened and what was the outcome.

Of our 27 missions over North Korea, we had flack and Mig threats on most nights.

We were third in line for takeoff over North Korea, and the control tower started each B-29 at three-minute intervals. All of us on the crew could hear the communication from the tower to the pilot. When we heard the control tower say, “Shelter 45, prepare for takeoff,” and the airplane turned off the taxiway to the very end of the runway and powered up all four engines to maximum power, we knew we were on our way to our first combat mission. The left gunner and I confirmed the flap position to the pilot by saying, “A/C left flap at 25 degrees, sir.” I would repeat the same for the right side. The control tower said, “Shelter 45, begin your roll.” We started out very slow, and as I observed the landing gear on my side of the airplane, I could see the tires come up from their compressed look as we gained speed down the runway. Taking off with a loaded aircraft was much different than a takeoff with an unloaded B-29. I anxiously watched the runway pass quickly by, and we were still solid on the ground. Finally, as we neared the end of the runway, we began to fly. The pilot had used nearly all of the 7000 feet of runway available.

We slowly gained altitude and flew south to the ocean, then west several miles before crossing Japan to the Sea of Japan and our destination, North Korea. Halfway between Japan and Korea, there was a location designated for the gunners to test fire their machine guns. The A/C gave us the okay to fire our guns, and all were in working order. We just fired a short burst from each turret.

We left Yakota A.F.B. at 7:00 pm, 1900 hours military time, and when we tested our machine guns, it was now 9:00 pm or 2100 hours. An hour later, we entered North Korea and listened to the pilot make radio contact with the ground controller for bombing troops, supplies, and truck convoys behind the front lines. The North Koreans would try to intercept the radio message from the ground to the airplane and would use perfect English to try and vector the bomb drop on our own troops; thus, the reason for the code word. The Ground Controller gave us a vector and asked us to drop 15 of our 500-pound bombs on the first drop. The Bombardier opened the bomb bay doors and prepared for the drop. The radar operator gave the pilot directions to the target, and just before the bomb was released, the pilot asked for the ground controller to give the code word to authenticate the drop. The ground controller said, “Mickey Mouse two,” so we knew it was not a North Korean giving us direction, and the Bombardier released fifteen 500-pound bombs. We could watch the bombs leave the aircraft, and not long after they left, we watched them explode along the enemy front line. The ground controller confirmed our strike, thanked us, then gave us a new vector with a different heading. This time he asked us to release ten bombs on this heading, and in the last vector, he asked us to release the remaining fifteen bombs. As the bombs left the airplane, the lighter loads made the B-29 rise up several hundred feet. We could see artillery fire and spotlights that were used by our troops to try and see enemy targets. The North Koreans fired 20mm at us, but it would only come up halfway to our altitude. Fortunately, they didn’t have their German 88s to fire at us on the front lines.

We left the front line area and proceeded east out over the Sea of Japan and home. The engineer throttled back the engines for a slow cruise and efficient fuel conservation, and the pilot began a slow descent toward the coast of Japan. The tail gunner left his post and came up to our compartment to warm himself up. It was now 1:00 am or 100 hours, and it would be hard to find anyone awake on the airplane. We had been in the air for six hours, and everyone was dead tired. We had one more hour before returning to the landing pattern at Yakota.

Our approach and landing at Yakota from almost every mission seemed cloudy and foggy. GCA (Ground Control Approach) often picked us up as we entered the landing pattern. Those of us in the back of the airplane could hear the GCA operator talk the pilot down to the runway for his landing. He would tell the pilot that he didn’t need to acknowledge further transmissions and would say, “Bring your aircraft left. You’re now on the center line. Bring your aircraft. You’re now on the center line.” And he would continue this conversation with the pilot as he flew the airplane down the flight path. It was the left and right gunner’s job to confirm with the pilot that the left and right flaps were at 45 degrees for landing and that the gear was fully down. When our airplane passed over the fence, the GCA operator told the pilot to take over his aircraft and land. Hopefully, we were over the end of the runway, and the pilot had a good full view of the runway.

We would taxi back to our hard stand and shut all four engines down, then we loaded into a six-by truck and went back to operations for a de-briefing. Two officers met our crew in a private room and let each one of us tell what we saw and observed during the mission. They recorded everything we had to say and had liquor available for any of us who wanted to drink. I don’t think any of our crew tried the liquor. After our interrogation, we went to the mess hall for breakfast. The cooks let us have whatever we wanted: eggs, toast, bacon, fruit, juice, and whatever else we liked. Air crews were treated very well when it came to grub. After eating, we returned to our little Quonset hut and sacked out. It was now 4:00 am. All of us were dead tired, and sleep came quickly. Most of us slept until noon, then went to the mess hall for dinner. After dinner, we went back out to our airplane to do a Post Flight, where we cleaned and checked our guns and ensured everything was in good order for the next time we flew. The ground crew was going over all four engines to correct any mechanical problems.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

My favorite was 345th Bomb Sq. Long-range missions out of Japan over North Korea concluded our first combat mission flown on May 25, 1952.

Each day we would all check the blackboard in the Operations Room to see if our crew was on the board scheduled to fly the next mission. Our next mission came on May 31 (call sign “Apricot 69”), then Jon June 3, our third mission (call sign “Sonny boy 28”), bombing a bridge. Our fourth mission was June 9 (call sign “Good Book 45”). Our target was the Huichol Rail Bridge. The fifth mission was the Huichol Rail Bridge again on June 12 (call sign “Paper doll 32”). The sixth mission was June 15 (the call sign was “King Cole 49”), and we dropped 40 five-hundred-pounders on “Sing Hung Dong RR Bridge.” This was our first mission with spotlights and heavy flak. The seventh mission was on June 17, 1952, with our call sign, “War River 50.” The target was CChinnampo’smarshalling yard. June 19 was our eighth mission (call sign “Lefty 38P). The target was the Huichol RR Bridge again, flak but no spotlights.

June 24 was our ninth mission, and we called this a “milk run” because it was a “Primer Mission” where we dropped on the front lines. Our call sign was “Hopscotch 53.” We took off at 1830 hours from Yakota (6:30 p.m.) with forty 500-pound bombs. We arrived over the front lines along the 38th parallel of Korea at 2230 hours. The pilot got directions from the ground controller for our first drop. He requested five bombs on our first drop. After dropping five bombs, the ground controller called for ten bombs on the next target. When the pilot asked for the code word just before the drop, he couldn’t give it to us, so we aborted the drop. The controller then gave us another vector to a new target. This time we dropped 15 bombs. We now had 20 still on board. The controller gave us another vector, and when we were about ready to drop, the controller couldn’t give us the proper code word, so we didn’t drop again. We had been over the front lines for over an hour and needed to head back home for lack of fuel. The controller told us to go north of the front lines and drop our remaining bomb load on a target of opportunity. The Bombardier zeroed in on a light and salvoed the remaining bomb load.

We then headed for home across the Sea of Japan. When we approached Yakota A.F.B., we were told that weather conditions made it impossible for us to land because of dense fog and heavy rain. We were directed to go to Haneda airport in Tokyo to land. When we got there, they informed us that we couldn’t land because of dense fog and to fly south, looking for an open airfield to land. The pilot found a fighter base in Southern Japan that was open. They had light rain but plenty of visibility for landing. We are going to land at the base of Ashita, a fighter base with a 66000-foot runway. We had been flying for more than ten hours and were just about out of fuel. The flight engineer informed Captain Funk that we would have to land on our first try because there was not enough fuel to go around and make another attempt.

As we approached the field to land, the wing flaps were set at 25 degrees rather than the usual 45 degrees. Those of us in the gunner’s compartment saw a lot of runway pass before the main gear touched the runway, then we saw steel matting.

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect back on to this day.

The day crash landed our B-29 with only one injury was our eighth mission (call sign “Lefty 38P). The target was the Huichol RR Bridge again, flak but no spotlights.

June 24 was our ninth mission, and we called this a “milk run” because it was a “Primer Mission” where we dropped on the front lines. Our call sign was “Hopscotch 53.” We took off at 1830 hours from Yakota (6:30 p.m.) with forty 500-pound bombs. We arrived over the front lines along the 38th parallel of Korea at 2230 hours. The pilot got directions from the ground controller for our first drop. He requested five bombs on our first drop. After dropping five bombs, the ground controller called for ten bombs on the next target. When the pilot asked for the code word just before the drop, he couldn’t give it to us, so we aborted the drop. The controller then gave us another vector to a new target. This time we dropped 15 bombs. We now had 20 still on board. The controller gave us another vector, and when we were about ready to drop, the controller couldn’t give us the proper code word, so we didn’t drop again. We had been over the front lines for over an hour, and we needed to head back home for lack of fuel. The controller told us to go north of the front lines and drop our remaining bomb load on a target of opportunity. The Bombardier zeroed in on a light and salvoed the remaining bomb load.

We then headed for home across the Sea of Japan. When we approached Yakota A.F.B., we were told that weather conditions made it impossible for us to land because of dense fog and heavy rain. We were directed to go to Haneda airport in Tokyo to land. When we got there, they informed us that we couldn’t land because of dense fog and to fly south, looking for an open-air field to land at. The pilot found a fighter base in Southern Japan that was open. They had light rain but plenty of visibility for landing. The base we were going to land at was Ashiya, a fighter base with a 6000-foot runway. We had been flying for more than ten hours and were just about out of fuel. The flight engineer informed Captain Funk that we would have to land on our first try because there was insufficient fuel to go around and make another attempt.

As we approached the field to land, the wing flaps were set at 25 degrees rather than the usual 45 degrees. Those of us in the gunner’s compartment saw a lot of runway pass before the main gear touched the runway, then we saw steel matting Lieutenant Crandall and Sergeant Justice to the hospital. They checked the rest of us for injury, then found us quarters to clean up and rest. Captain Funk came to us gunners and asked us to return to the airplane and take the flash suppressers off all machine guns. They were top-secret pieces of equipment and screwed onto the end of each barrel to prevent gunfire flash. While we were taking the flash suppressers off, Joe checked the fuel tanks the on the airplane and found them all empty and dry. We would run out of gas, trying to go around the pattern for a better landing attempt.

I had my Argus C-3 camera with me, so I took four pictures of the crash. An air police officer approached me and said, “Give me your camera; you cannot take photographs here.” I turned to him and said, “I was on that airplane, and I want these pictures to show what this crew went through.” He turned around and said no more to me. The Red Cross gave us a toothbrush and a razor for our evening toiletries; then, we went to chow. Captain Funk informed us that Yakota was sending a C-47 down to pick us up and return to our home base the following day. We stayed overnight at Ashiya A.F.B. and left the next morning on a C-47 for Yakota A.F.B. Lieutenant Crandall was kept in the hospital and was going to be rotated back to the US as soon as he could travel.

When we returned to Yakota, it was June 26, and our crew needed a bombardier and a flight engineer. Lieutenant Crandall had broken ankles, and Justice had a hurt back and figured he had flown enough missions to be still alive. Captain Funk was grounded due to an investigation of the accident. It was determined that the flaps should have been at 45 degrees rather than 25 degrees for the landing. So now we needed a new aircraft commander. The wing commander, Colonel Palister, assigned Lieutenant Kinnard as our new aircraft commander, Lieutenant Zitano as our Bombardier, and Sergeant Eversall as the new flight engineer.

It was July 13, 1952, before we flew another combat mission. Needless to say, we needed an airplane, and they flew a new one in from the States. We got together as a crew and decided to name our airplane “Police Action” because they called this war with Korea a United Nations Police Action. We hired a Japanese painter to paint a pretty young lady on the front of our airplane. She wore a bolero and had a six-gun on her hip. This airplane was great and had the best-looking picture and name in the 98th Bomb Wing. Our entire crew was unanimous about that! We flew a local test flight with our new B-29 and then got ready to get back in the rotation of flying combat. We were all very impressed with Lieutenant Kinnard and his ability to fly the B-29. He was one excellent pilot, for sure. Lieutenant Zitano and Sergeant Eversall fit right into our crew.

On July 13, 1952, we flew our tenth combat mission. Our call sign was “Silver 42,” and our target was the “Kowan Marshalling Yards.” We had flak and searchlights on this mission, and there were no hits on our aircraft, thank you.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

I gained maturity and life experiences, And I received GI Bill help with my Dental School.

We all thought we should get credit for two missions because we went over the target twice and had no suck luck. Our call sign for this mission was “Phantom 125.” Our 18th mission was on August 21 against the “Hamhung Supply Area,” and our call sign was “Smokey Stover 15.”

On this mission, after dropping our bombs, I always turned the light on in the rear bomb bay to see that all the bombs had left the airplane. To our surprise, two bombs hadn’t dropped. When we got out over the Sea of Japan and radar couldn’t see anything below us, I had the Bombardier open the rear bomb bay doors, then I went out on the narrow catwalk to release the bombs from their shackles. It took a screwdriver to trip the bomb release. This was a very dangerous operation with bomb bay doors open and 200mph wind blowing in.

Our 19th mission was on August 25 against the “Anju Supply Center” (call sign “Shelter 9”). Our 20th mission was August 29 (call sign “Tango 1”) against the “Chosen Hydroelectric Plant.” Colonel Palister flew with us on this mission and was wing commander for the 98th Bomb Wing. We had heavy flak and spotlights and Migs on us over the target. Sergeant Jensen was an ECM operator with us this night, and he was able to jam the 88s and spotlights’ radar so they couldn’t zero in on us. When we approached the target, and the flak was coming up thick enough to walk on, Colonel Palister turned to Lieutenant Kinnard and said, “Do we have to fly through that?” Reply, “Yes, we do!”

After our 20th mission, all of the gunners were recommended for promotion, and Joe and “J” were awarded another stripe making both of them Sergeants. Dean and I were interviewed by a board of officers to see if we were worthy of another stripe to become Staff Sergeants. We all passed and looked forward to an increase in pay.

Our 21st mission was September 3 (the call sign was “Orangeade 10”), and our target was the “Suiho Hydroelectric Plant.” We had eight 2000-pound cement-penetrating bombs with a 1/10th second delay fuse in each bomb, and Lieutenant Robb dropped them dead center on the target and obliterated this plant. We had no opposition on this bomb run. There was almost no Hydroelectric power in North Korea, and we had turned out their lights.

Our 22nd mission was on September 6 (the call sign was “Flower 19”) against the “Pyongyang Supply Area.” Our 23rd mission was on September 9 (the call sign was “Patrick 17”). The target was “Sopo Supply Area.” Our 24th mission was September 19 (call sign “Penetrate 10”). Our target was “Chigyong Supply Center.” The 25th mission, supposedly our last mission, was a night mission at 16,000 feet (call sign “Sickbay 53.”) We flew this mission on September 24.

I matured, and then I had MiGs when they were flying daylight missions, thus the change to night combat. Colonel flew with us and wanted to get a combat mission on his record.

The B-29 was old and tired but served us well and brought us back to Japan each time, even though we had flak damage and a crash landing. We arrived in Japan in April 1952 and left in October 1952, after we finished our combat tour. Each mission was a story in itself, and we were glad to get it behind us and return to the States.

We later learned that our replacement crew flying “Police Action” had been shot down over North Korea.

I am the only member of the crew still alive now. It’s been 70 years since we shared combat and went in harm’s way on those dark nights over North Korea.

After I got out, I returned to Pre Dental and then Dental School, which had been interrupted by the war.

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

Air Medal with 2 clusters.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

Our Aircraft Commander had high morals and was very religious. He was an influence on the whole crew and our military service.

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

I am the last one now. Every third year we would gather for a crew reunion in different towns or Military Museums.

Crew Roster:

Cpt Donald O. Funk, Aircraft Commander From Utah

Later replaced by 1/Lt Max E. Kinnard, Aircraft Commander From California

1/Lt Robert N. Sorensen, Pilot From Utah

1/Lt Garland L. Reasor Navigator From Tennessee

1/Lt Horace B. Crandall Bombardier From Idaho

Later replaced by 1/Lt Frank P. Zitano Bombardier From California

1/Lt Donald S. Robb, Navigator From Colorado

M/Sgt Alex R. Justiss, Engineer From Texas

Later replaced by M/Sgt Cecil P. Eversoll Engineer

S/Sgt Jerry J. Cox Radio Opp. California

S/Sgt Joseph R. English CFC Gunner Louisiana

S/Sgt Dean S. Allan Left Gunner Utah

S/Sgt Kenneth L. Russell Right Gunner Utah

S/Sgt Jay L. Lundell Tail Gunner Utah

Can you recount a particular incident from your service, which may or may not have been funny at the time, but still makes you laugh?

That time we totaled that B-29. We were so low on fuel that two engines quit. On our final approach, we crashed that plane, and all walked away from it except the Bombardier with a broken ankle.

What profession did you follow after your military service, and what are you doing now? If you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

I went back to college, finished Dental School, and practiced in Salt Lake City. I am retired now.

What military associations are you a member of, if any? What specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

I thank the VA for help with my college tuition. [GI Bill}.

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

You grow up in a hurry and learn discipline and pride. It is built in and after the military. I was 20 years old, flying in combat.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with?

Doing some research through photos and pages brings back many memories.

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

Thanks for this. Lee Reasor was my father. I’m currently editing his military history for some of my grandchildren. The details you provide are very informative. I grew up with the photographs of the hard landing. I wish I could see your original photographs. The history I’m working from is a second-generation 1980s photocopy.