The Sand Creek Massacre, occurring on November 29, 1864, was one of the most infamous incidents of the Indian Wars. Initially reported in the press as a victory against a bravely fought defense by the Cheyenne, later eyewitness testimony conflicted with these reports, resulting in a military and two Congressional investigations into the event. Two of those eyewitnesses were cavalry officers Capt. Silas Soule and Lt. Joseph Cramer who had the courage to order their men not to take part in the slaughter. It was these two that were also the driving force in getting the government to conduct more in-depth investigations on what really happened at Sand Creek.

Conflicts and Tensions Before the Sand Creek Massacre

The causes of the Sand Creek massacre and other atrocities inflicted on the Indians were rooted in the long conflict for control of the Great Plains of eastern Colorado and to the river to the Nebraska border to the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Around the same time, gold and silver were discovered in the Rocky Mountains, resulting in a gold rush by thousands of whites seeking their fortunes. In no time at all, tensions between the Indians and the gold miners came to a boiling point, resulting in deadly attacks on wagon trains, mining camps, and stagecoach lines. But not all the Indians were renegades.

There were some who believed both Native Americans and white Americans could live in peace. One was Chief Black Kettle. Early in 1861, Black Kettle, along with some Arapahoe leaders, accepted a new settlement with the Federal government. The Native Americans ceded most of their land but secured a 600-square mile reservation and annuity payments. In the decentralized political world of the tribes, chiefs Black Kettle and White Antelope and their fellow delegates represented only part of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. Many did not accept this new agreement, called the Treaty of Fort Wise, and continued to conduct deadly raids on settlers and miners.

As the conflict between the Indians and white settlers in Colorado continued, a large number of the Cheyenne and Arapaho were resigned to negotiating a peace, despite pressure from the less friendly bands of Indians, soldiers, and white settlers. In July 1864, Colorado’s territorial governor John Evans sent a circular to the Plains Indians, inviting those who were friendly to go to a place of safety at Ft. Lyon on the eastern plains, where their people would be given provisions and protection by the United States troops.

Black Kettle, chief of around 800 most Southern Cheyenne, led his band and some Arapahos under Chief Niwot, to Ft. Lyon in compliance with provisions of peace held in Denver in September 1864.

After a while, the Native Americans were requested to relocate to Bing Sandy Creek, less than 40 miles northwest of Ft. Lyon, with the guarantee of “perfect safety” remaining in effect. The Dog Soldiers of the Cheyenne and Arapaho bands who were responsible for many of the deadly attacks and raids on whites were not part of this encampment.

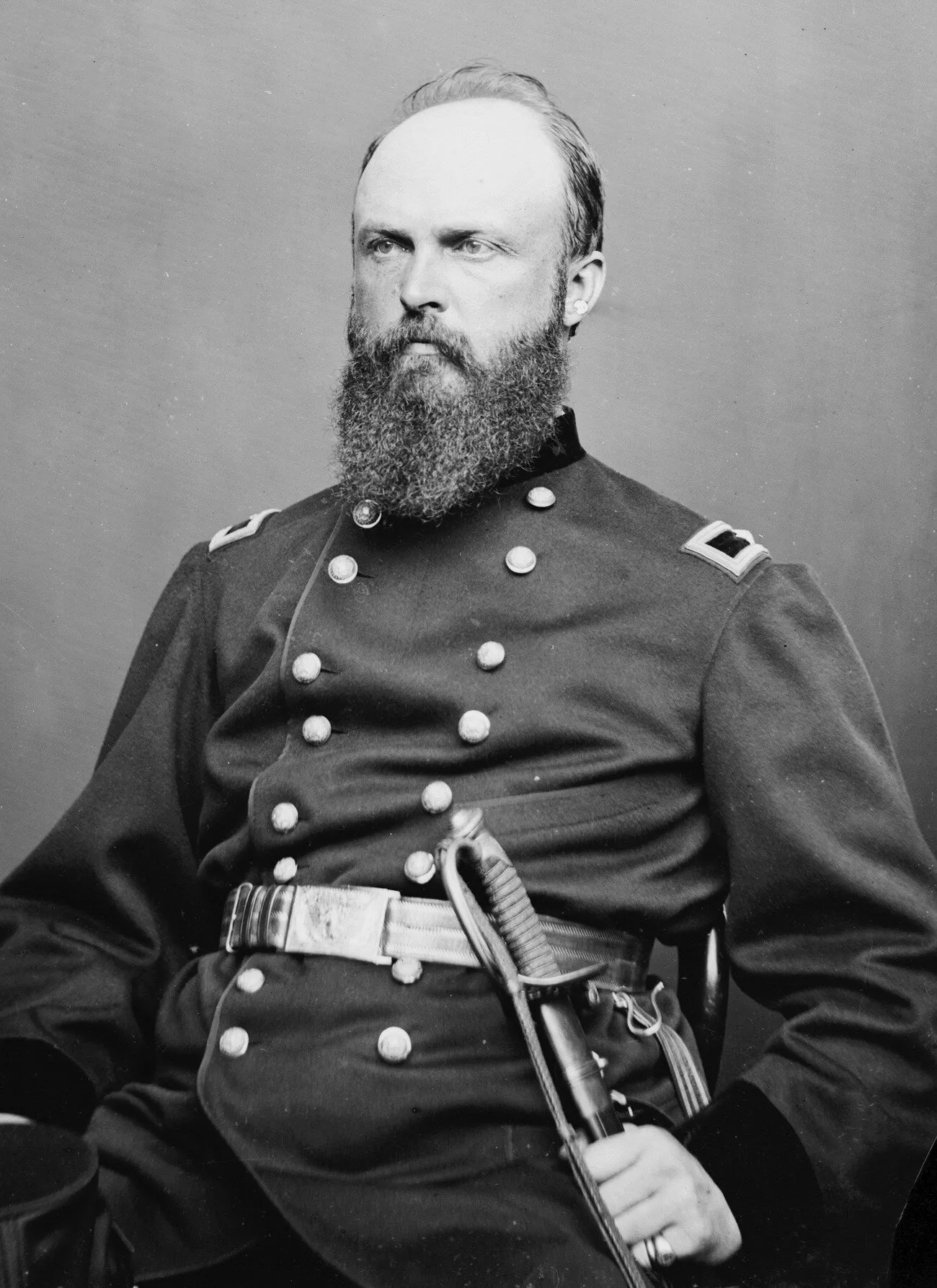

But violence between the Native Americans and the miners continued to increase, so territorial governor John Evans sent a Voluntary Militia commander by the name of Col. John Milton Chivington to quiet the Indians.

Though once a member of the clergy, Chivington’s compassion did not extend to the Indians and his desires to extinguish them all was well known as he often said, “Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians! I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians. Kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice.”

In the spring of 1864, while the Civil War raged in the east, Chivington launched a campaign of violence against the Cheyenne and their allies, his troops attacking any and all Indians and razing their villages. The Cheyenne, joined by neighboring Arapaho, Sioux, Comanche, and Kiowa in both Colorado and Kansas, went on the defensive warpath.

Without any declaration of war, in April 1864, Colorado soldiers began attacking and destroying a number of Cheyenne camps. On May 16, 1864, a detachment under Lt. George S. Eayre crossed into Kansas and encountered Cheyenne in their summer buffalo-hunting camp at Big Bushes, near the Smoky Hill River. Cheyenne chiefs Lean Bear and Star approached the soldiers to signal their peaceful intent, but they were shot down by Eayre’s troops. This incident touched off a war of retaliation by the Cheyenne.

In response, territorial governor Evans and Col. Chivington reinforces their militia, raising the Third Colorado Cavalry of short-term volunteers who referred to themselves as the “Hundred Dazers.”

After a summer of scattered small raids and clashes, the Cheyenne and Arapaho were ready for peace, and as a result, the Indian representatives met with Evans and Chivington at Camp Weld outside of Denver on September 28, 1864. Though no treaties were signed, the Indians believe that by reporting and camping near army posts, they would be declaring peace and accepting sanctuary.

However on the day of the “peace talks,” Chivington received a telegram from Gen. Samuel Curtis (his superior officer) informing him that “I want no peace till the Indians suffer more. No peace must be made without my directions.”

Unaware of Curtis’s telegram, Black Kettle and some 550 Cheyenne and Arapaho, having made their peace, traveled south to set up camp on Sand Creek under the promised protection of Ft. Lyon. Those who remained opposed to the agreement headed north to join the Sioux.

The Violent Assault on Black Kettle’s Camp

Knowing that the Indians had surrendered, Chivington and 425 men of the 3rd Colorado Cavalry and 250 men of the First Colorado Cavalry set out for Black Kettle’s encampment along Sand Creek. James Beckwourth, noted frontiersman, acted as a guide for Chivington.

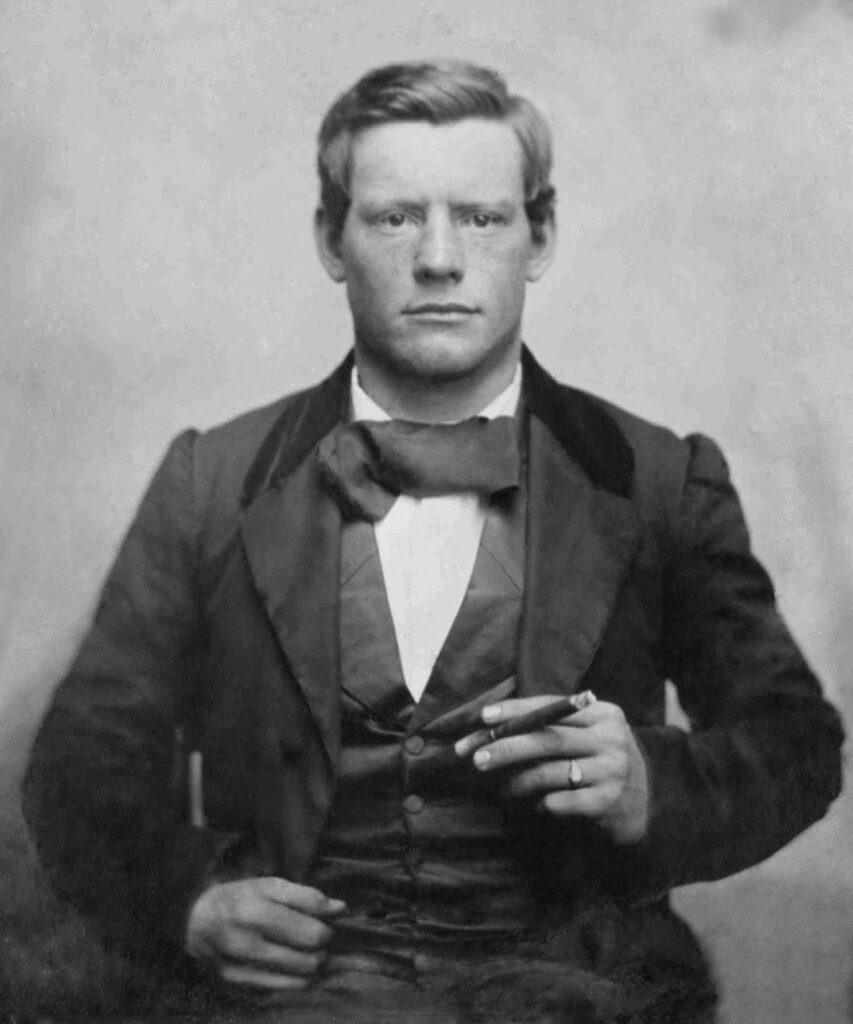

The night before the Sand Creek Massacre, Capt. Silas Soule, the Commander of Company D, 1st Colorado Cavalry, attempted with great emotion to convince Chivington to not attack Black Kettle’s peaceful Indian village at Sand Creek. Soule did so with such passion that Chivington threatened to have him put in chains. Only when Chivington assured him that camp would not be attacked, did Soule cease his objections.

The following morning, Chivington ignored his promise to Soule. Upon reaching the outskirts of the Sand Creek Indian Village, Chivington noted that the ever trusting Black Kettle had raised both an American and a white flag of peace and surrender over his tepee – as the Ft. Lyon commander had advised. This was to show he was friendly and to forestall any attack by the Colorado Soldiers.

This sign of peace was ignored by Chivington. All he could see was an easy victory at hand. He raised his arm, giving the signal to attack. Cannons and rifles began to pound upon the camp as the Indians scattered in panic. Watching the beginning of the senseless slaughter, Soule ordered his men to hold fire and stay put rather than ride down to the Village as the rest of Chivington’s forces attacked the camp.

Lt. Joseph Cramer also watched in horror as Army troops swarmed onto Sand Creek, murdering men, women, and children without hesitation. Not only did these men butcher peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho, they then mutilated the bodies, looted the village and killed prisoners. Like Soule, Cramer ordered his men to stay where they were and not get involved in the brutal attack.

The Cheyenne, lacking artillery, could not make much resistance. Some of the natives cut horses from the camp’s herd and fled up Sand Creek to a nearby Cheyenne camp on the headwaters of the Smoky Hill River.

They were pursued by the troops and fired on, but many survived. Cheyenne warrior Morning Star said that most of the Indian dead were killed by cannon fire, especially those firing from the south bank of the river at the people retreating up the creek.

The frenzied soldiers began to charge, hunting down men, women, and children, shooting them unmercifully. A few warriors managed to fight back allowing some members of the camp to escape across the stream.

They were pursued by the troops and fired on, but many survived. Cheyenne warrior Morning Star said that most of the Indian dead were killed by cannon fire, especially those firing from the south bank of the river at the people retreating up the creek.

The troops kept up their indiscriminate assault for most of the day, during which numerous atrocities were committed. One lieutenant was said to have killed and scalped three women and five children who had surrendered and were screaming for mercy. Finally breaking off their attack they returned to the camp killing all the wounded they could find before mutilating and scalping the dead, including pregnant women, children, and babies. They then plundered the teepees and divided up the Indians horse herd before leaving.

By the time the attack was over, as many as 150 Indians lay dead, most of which were old men, women, and children. Losses on the cavalry side were only 9 or ten men, with about three dozen wounded. Black Kettle and his wife followed the others up the stream bed, his wife being shot several times, but somehow managed to survive.

The survivors, over half of whom were wounded, sought refuge in the camp of the Cheyenne Dog Warriors (who had remained opposed to the peace treaty) at Smokey Hill River. Many of the Indians joined the Dog Soldiers, deciding there could be no successful negotiations with the white men and were waging war against them.

The Colorado volunteers returned to Denver, exhibiting their scalps, to receive a hero’s welcome. When news of the Battle of Sand Creek reached Eastern newspapers, it was reported as a major victory against a bravely-fought defense by the Cheyenne and Arapaho.

Soule and Cramer Expose the Sand Creek Massacre

As details of what really happened at the Battle of Sand Creek came out, however, the U.S. public was shocked by the brutality of the massacre. The congressional investigation subsequently determined the crime to be a “sedulously and carefully planned massacre.” When asked at the military inquiry why children had been killed, one of the soldiers quoted Chivington as saying, “nits make lice.” Though Chivington was denounced in the investigation and forced to resign, neither he nor anyone else was ever brought to justice for the massacre.

After the brutal slaughter of those who supported peace, many of the Cheyenne, including the great warrior Roman Nose and many Arapaho joined the Dog Soldiers. They sought revenge on settlers throughout the Platte valley, including an 1865 attack on what became Fort Caspar, Wyoming.

As word of the massacre spread among the Indians of the southern and northern plains, their resolve to resist white encroachment stiffened. An avenging wildfire swept the land and peace returned only after a quarter of a century.

Black Kettle, who had raised a U.S. flag in a futile gesture of fellowship, survived the massacre, carrying his badly wounded wife from the field and straggling east across the wintry plains. The next year, in his continuing effort to make peace, he signed a treaty and resettled his band on reservation land in Oklahoma. He was killed there in 1868, in yet another massacre, this one led by George Armstrong Custer.

Immediately After the Merciless Siege at Sand Creek, Soule and Cramer Told the Truth

While the Sand Creek massacre has been the subject of numerous books, much less attention has been given to the two heroes of this horrific event. Refusing to participate, Capt. Silas Soule and the men of Company D of the First Colorado, along with Lt. Joseph Cramer and the men of Company K, bore witness to the incomprehensible.

Immediately after the merciless siege at Sand Creek, Soule and Cramer reported Chivington’s attack quickly descended into a frenzy of killing and mutilation, with soldiers taking scalps and other grisly trophies from the bodies of the dead. Soule, a devoted abolitionist, was dedicated to the rights of all people. He stayed true to his convictions in the face of insults and even a threat of hanging from Chivington the night before at Ft. Lyon.

In the weeks following the massacre, Soule and Crammer wrote letters to Maj. Edward “Ned” Wynkoop, the previous commander at Ft. Lyon who had dealt fairly with the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Both harshly condemned that massacre and the soldiers that carried it out. Soule’s letter details a meeting among officers on the eve of the attack in which he fervently condemned Chivington’s plan asserting “that any man who would take part in murders, knowing the circumstances as we did, was a low lived cowardly son of a bitch.”

Despite threats against his life, Soule was the first to testify against Chivington during the Army’s investigation in January 1865. Cramer followed, describing the horror he and his men witnessed at the Sand Creek Massacre. Their testimony, along with others present at the massacre, incriminated Chivington and forced him to resign his role as commander of the Second Cavalry Regiment. He never spent a day in jail, however. Nor did any others willingly taking part in the bloodbath.

On April 1, 1865, Soule married Thersa A. “Hersa” Coberly. Twenty-two days later, on April 23, 1865, after testifying against Chivington, Soule was on duty as Provost Marshal in Denver when he went to investigate guns fired at 10:30 pm. With his pistol out, he went around the corner and faced Charles Squier, a former Sergeant in the Second Cavalry. Soule fired the first shot and wounded Squier’s left arm, but Squier fired a bullet into Soule’s right cheekbone. Soule was dead before help could arrive. Squire dropped his pistol and ran before he could be arrested by the authorities and fled to South America. He was never brought to justice. It was suspected at the time the Col. Chivington directed the assassination.

After testifying against Chivington in the spring of 1865, Cramer mustered out of the regiment and moved back east where married Hattie Phelps. The newly married man sought a career as an Indian agent, but eventually moved to Solomon, Kansas and found a position as a clerk. There, Hattie died three years into their marriage.

Following his wedding to Augusta Hunt in 1869, a bed-ridden Cramer passed away from a back injury he had suffered while in the cavalry. He was thirty-three. He died shortly after selection to the Sheriff’s office of Dickinson County, Kansas.

Beyond a doubt, Silas Soule and Joseph Cramer were men of strong character and moral courage. Each was a man of conviction, knowing the right thing to do and had the will to do it, no matter what the personal consequences.

Both rejected the violence and genocide inherent in the “conquest of the West.” They did so by personally refusing to take part in the murder of peaceful people while ordering the men under their command to stand down. Their example breaks the conventional frontier narrative that has come to define the clash between Colonial settlers and Native peoples as one of civilization versus savagery.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the Sand Creek Massacre, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

Sad, but amazing. The media of the day were liars just as they are today. As the saying goes: ‘Believe nothing that you hear and only half of what you see’.

Good reporting,good distillation of reports, and good publishing. I am a Vietnam vet, and thanks be, we only engaged in combat with Vietnamese in the field, never in a village. That would have been tough, but we’ve have done it. War hardens you. You get used to seeing dead people. That’s one reason why war is terrible, and the effects last a lifetime, or at least it has with me and my platoon friends when we talk.

As a retired military man (USAF), and veteran of two tours in Vietnam I have witnessed my share of the “atrocities” of war.

I’ve studied and read about the Indian wars for over fifty years and one aspect always stands out, in the end: its “politics”.

A perfect example is George A. Custer. He was being prepped to become president when he was killed. Many military men have gone on to become great politicians, notably John F. Kennedy and Dwight Eisenhower.

In all my studies the Indians have won a few battles but ultimately lost. They are now pretty much regulated to several reservations and are still regarded by many as “second grade citizens”, or ‘low class”. In my younger years I was what was consider “poor white trash”, the same status as the Indians.

The Sand Creek Massacre was a great tragedy and forever a black mark on the Army. Let’s not forget it and hope that the world situation today doesn’t become another even bigger black mark.