“The Battle of Dien Bien Phu, fought from March 13 to May 7, 1954, was a decisive Vietnamese military victory that brought an end to French colonial rule in Vietnam.”

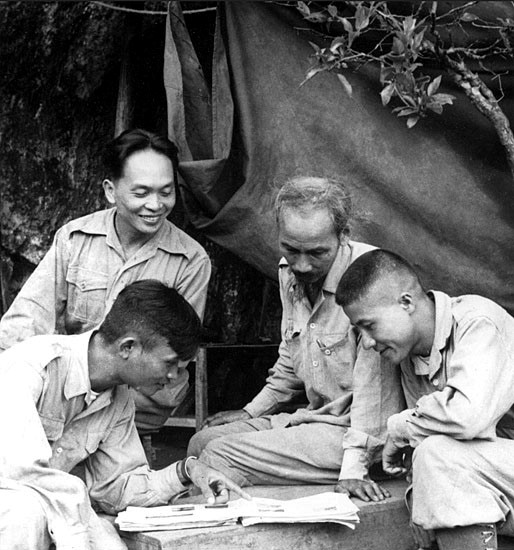

The causes of the Vietnam War trace their roots back to the end of World War II. A French colony, Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, & Cambodia) had been occupied by the Japanese during the war. In 1941, a Vietnamese nationalist movement, the Viet Minh, was formed by Ho Chi Minh to resist the occupiers. A communist, Ho Chi Minh, waged a guerilla war against the Japanese with the support of the United States. The Battle of Dien Bien Phu that settled the fate of French Indochina was initiated in November 1953.

Ho Chi Minh Proclaimed the Independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam

On September 2, 1945, hours after the Japanese signed their unconditional surrender in World War II, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam, hoping to prevent the French from reclaiming their former colonial possession. In 1946, he hesitantly accepted a French proposal that allowed Vietnam to exist as an autonomous state within the French Union, but fighting broke out when the French tried to reestablish colonial rule by shelling the city of Haiphong in December 1946 and forcibly reentered the capital, Hanoi. These actions began a conflict between the French and the Viet Minh, known as the First Indochina War (1946-1954) and referred to as the Anti-French War by the Vietnamese.

Beginning in 1949, the Viet Minh fought an increasingly effective guerrilla war against France with military and economic assistance from newly Communist China. Deeply concerned with the spread of Communism, the United States began supplying the French military in Vietnam with advisors and funding its efforts against the “red” Viet Minh.’

With the First Indochina War going poorly for the French, Premier Rene Mayer dispatched Gen. Henri Navarre to take command in May 1953.

Arriving in Hanoi, Navarre found that no long-term plan existed for defeating the Viet Minh and that French forces simply reacted to the enemy’s moves. Believing that he was also tasked with defending neighboring Laos, Navarre sought an effective method for interdicting Viet Minh supply lines through the region.

Working with Col. Louis Berteil, the “hedgehog” concept was developed which called for French troops to establish fortified camps near Viet Minh supply routes.

Supplied by air, the hedgehogs would allow French troops to block the Viet Minh’s supplies, compelling them to fall back. The concept was largely based on the French success at the Battle of Na San in late 1952. Holding the high ground around a fortified camp at Na San, French forces had repeatedly beaten back assaults by General Vo Nguyen Giap’s Viet Minh troops. Navarre believed that the approach used at Na San could be enlarged to force the Viet Minh to commit to a large, pitched battle where superior French firepower could destroy Giap’s army.

In June 1953, Maj. Gen. Rene Cogny first proposed the idea of creating a “mooring point” at Dien Bien Phu in northwest Vietnam. While Cogny had envisioned a lightly defended airbase, Navarre seized on the location for trying the hedgehog approach. Though his subordinates protested, pointing out that unlike Na San they would not hold the high ground around the camp, Navarre persisted and planning moved forward.

On November 20, 1953, Operation Castor commenced and 9,000 French troops were dropped into the Dien Bien Phu area over the next three days.

With Col. Christian de Castries in command, they quickly overcame local Viet Minh opposition and began building a series of eight fortified strong points transforming their anchoring point into a fortress by setting up seven satellite positions. Each was allegedly named after a former mistress of de Castries, although the allegation is probably unfounded, as the eight names begin with letters from the first nine of the alphabet (all but F). The fortified headquarters was centrally located, with positions “Huguette” to the west, “Claudine” to the south, and “Dominique” to the northeast. Other positions were “Anne-Marie” to the northwest, “Beatrice” to the northeast, “Gabrielle” to the north and “Isabelle” 3.7 miles to the south, covering the reserve airstrip. Over the coming weeks, de Castries’ garrison increased to 10,800 men supported by artillery and ten M24 Chaffee light tanks.

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu Settled the Fate of French Lndochina

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu that settled the fate of French Indochina was initiated in November 1953, when Viet Minh forces at Chinese insistence moved to attack Lai Chau, the capital of the T’ai Federation (in Upper Tonkin), which was loyal to the French. As Peking had hoped, the French Commander in Chief in Indochina, Gen. Henri Navarre, came out to defend his allies because he believed the T’ai “maquis” formed a significant threat in the Viet Minh “rear” (the T’ai supplied the French with opium that was sold to finance French special operations) and wanted to prevent a Viet Minh sweep into Laos. Because he considered Lai Chau impossible to defend, on November 20, Navarre launched Operation Castor with a paratroop drop on the broad valley of Dien Bien Phu, which was rapidly transformed into a defensive perimeter of eight strong points organized around an airstrip. When, in December 1953, the T’ais attempted to march out of Lai Chau for Dien Bien Phu, they were badly mauled by Viet Minh forces, forcing the garrison to flee towards Dien Bien Phu. En route, the Viet Minh effectively destroyed the 2,100-man column and only 185 reached the new base on December 22, 1953.

Viet Minh commander Vo Nguyen Giap, with considerable Chinese aide, massed approximately 50,000 troops and placed heavy artillery in caves in the mountains overlooking the French camp. On March 13, 1954, Giap launched a massive assault on strong point Beatrice, which fell in a matter of hours. Strong points Gabrielle and Anne-Marie were overrun during the next two days, which denied the French use of the airfield, the key to the French defense. Reduced to airdrops for supplies and reinforcement, unable to evacuate their wounded, under constant artillery bombardment, and at the extreme limit of air range, the French camp’s morale began to fray. As the monsoons transformed the camp from a dust bowl into a morass of mud, an increasing number of soldiers – almost four thousand by the end of the siege in May – deserted to caves along the Nam Yum River, which traversed the camp; they emerged only to seize supplies dropped for the defenders.

Despite these early successes, Giap’s offensives sputtered out before the tenacious resistance of French paratroops and legionnaires. On April 6, horrific losses and low morale among the attackers caused Giap to suspend his offensives. Some of his commanders, fearing U.S. air intervention, began to speak of withdrawal. Again, the Chinese, in search of a spectacular victory to carry to the Geneva talks scheduled for the summer, intervened to stiffen Viet Minh resolve: reinforcements were brought in, as were Katyusha multitube rocket launchers, while Chinese military engineers retrained the Viet Minh in siege tactics. When Giap resumed his attacks, human wave assaults were abandoned in favor of siege techniques that pushed forward webs of trenches to isolate French strong points. The French perimeter was gradually reduced until, on May 7, resistance ceased. The “Rats of Nam Yum” also became POWs when the garrison surrendered.

The shock and agony of the dramatic loss of a garrison of around fourteen thousand men allowed French Prime Minister Pierre Mendes to muster enough parliamentary support to sign the Geneva Accords of July 1954, which essentially ended the French presence in Indochina and the end of the First Indochina War (1946-1954), the precursor to the Vietnam War.

The Defeat at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu Marked the End of the First Indochina War

A disaster for the French, losses at Dien Bien Phu numbered 2,293 killed, 5,195 wounded, and 10,998 captured. Viet Minh casualties are estimated at around 23,000. The defeat at Dien Bien Phu marked the end of the First Indochina War and spurred peace negotiations which were ongoing in Geneva. The resulting 1954 Geneva Accords partitioned the country at the 17th Parallel and created a communist state in the north and a democratic state in the south. The resulting conflict between these two regimes ultimately led to the first phase of the Second Indochina War, better known as the Vietnam War, or the American War in Vietnam. It began in 1959 with North Vietnam’s first guerilla attacks against the South and ends with the fall of Saigon in 1973. American ground forces were directly involved in the war between 1965 and 1973.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about The Battle of Dien Bien Phu, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

0 Comments