The first major battle “The Battle of Manila Bay” of the Spanish-American War was also one of the U.S. Navy’s most resounding victories. Much has been written about how and why the Spanish-American War started, what the catalyst for the war was, and who’s to blame for it all. Once Spain declared war on the United States and the U.S. Congress responded in kind, the U.S. Navy was ready for action.

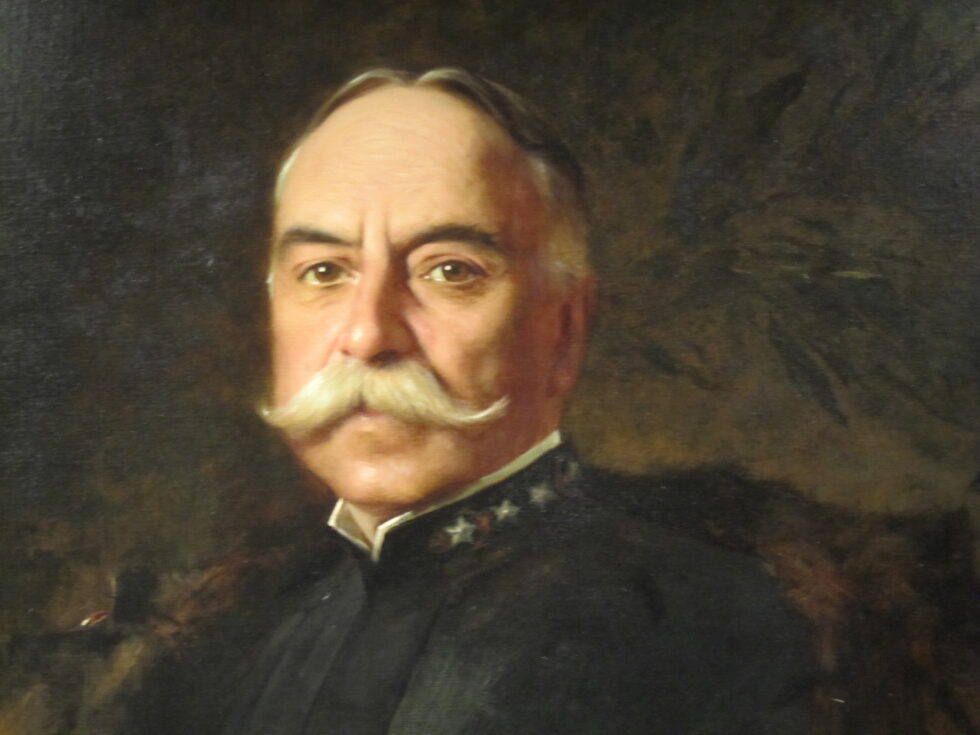

When the war broke out, the Spanish had a formidable squadron of ships stationed in the Philippines, and it was crucial for American war plans to knock it out. The man dispatched to do it was the commander of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron, Adm. George Dewey.

Composition of Forces in the Battle of Manila Bay

Dewey, until this point, was not a celebrated war hero or a known name, even in U.S. Navy circles. In 1898, he was a 60-year-old Civil War veteran who idolized Adm. David Farragut and served under him at the Battle of New Orleans. But then-Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt saw potential in the old sailor and arranged for him to be posted to the Asiatic Squadron in Hong Kong in January 1898. It was a good call.

The Naval War College‘s attack plans had drawn up in 1896 called for the Asiatic Squadron to simply deplete the Spanish fleet or divert its ships so they couldn’t be used elsewhere. But Roosevelt‘s orders to destroy the Spanish ships in the Philippines and Dewey set sail for the mission on April 27, 1898.

Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasaron was the commander of the Spanish Navy in the Philippines. He knew the Asiatic Squadron would be bearing down on his ships. He ordered the fortification of nearby Subic Bay to position his ships under a battery on Isla Grande and surprising Dewey from behind if he moved on Manila. But by the time the Spanish fleet arrived, the preparations were far from complete -, and Montojo knew the Americans were on the way.

Instead of lying in wait for the Americans, Montojo moved the ships to Manila and brought every gun he could to bear. Most of them were obsolete, and only a handful could fire far enough to hit incoming ships. The Spanish admiral was concerned about the town’s safety, so rather than wait for the Americans under the protection of coastal defenses, the Spanish fleet positioned itself under the guns of Cavite.

For Montojo, the added benefit was the shallow waters in this position. In case his sailors had to abandon ship, they would be able to escape. Montojo had every reason to be concerned about his men. While he had six steel ships, four with armored decks, many of his ships were also obsolete. His largest ship was made of wood. The American squadron bearing down on him was a far superior force without the shore batteries.

The Spanish believed Manila Bay was unnavigable at night without a Spanish pilot, so he expected Dewey to launch an attack on the morning of May 1st. But Dewey had waited to depart for the battle until he could get the latest intelligence from the U.S. Consul in Hong Kong. With the information provided, Dewey felt confident in moving at night on April 30th.

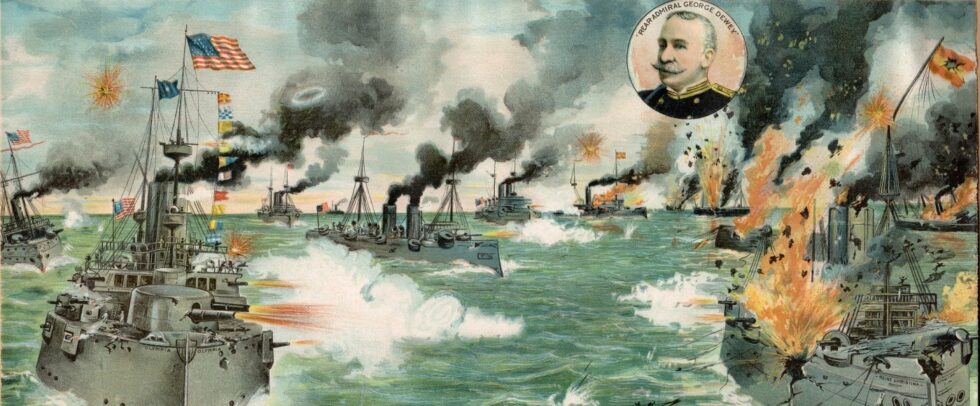

Dewey painted his white ships gray so they could move undetected under cover of darkness. They crept into Manila Bay through the Spanish channel single file. Dewey led the squadron aboard the flagship Olympia, which was followed by the USS Baltimore, Boston, Raleigh, Concord, and Petrel. The Revenue Cutter McCulloch and two cargo ships that sailed with the fleet held back as the Navy slipped into the bay.

At 5:15 in the morning on May 1st, the Spanish shore batteries and the fleet began firing at the Americans, but they were well out of range. Less than a half-hour later, in position to attack, Dewey gave the famous order, “You may fire when ready, Gridley.”

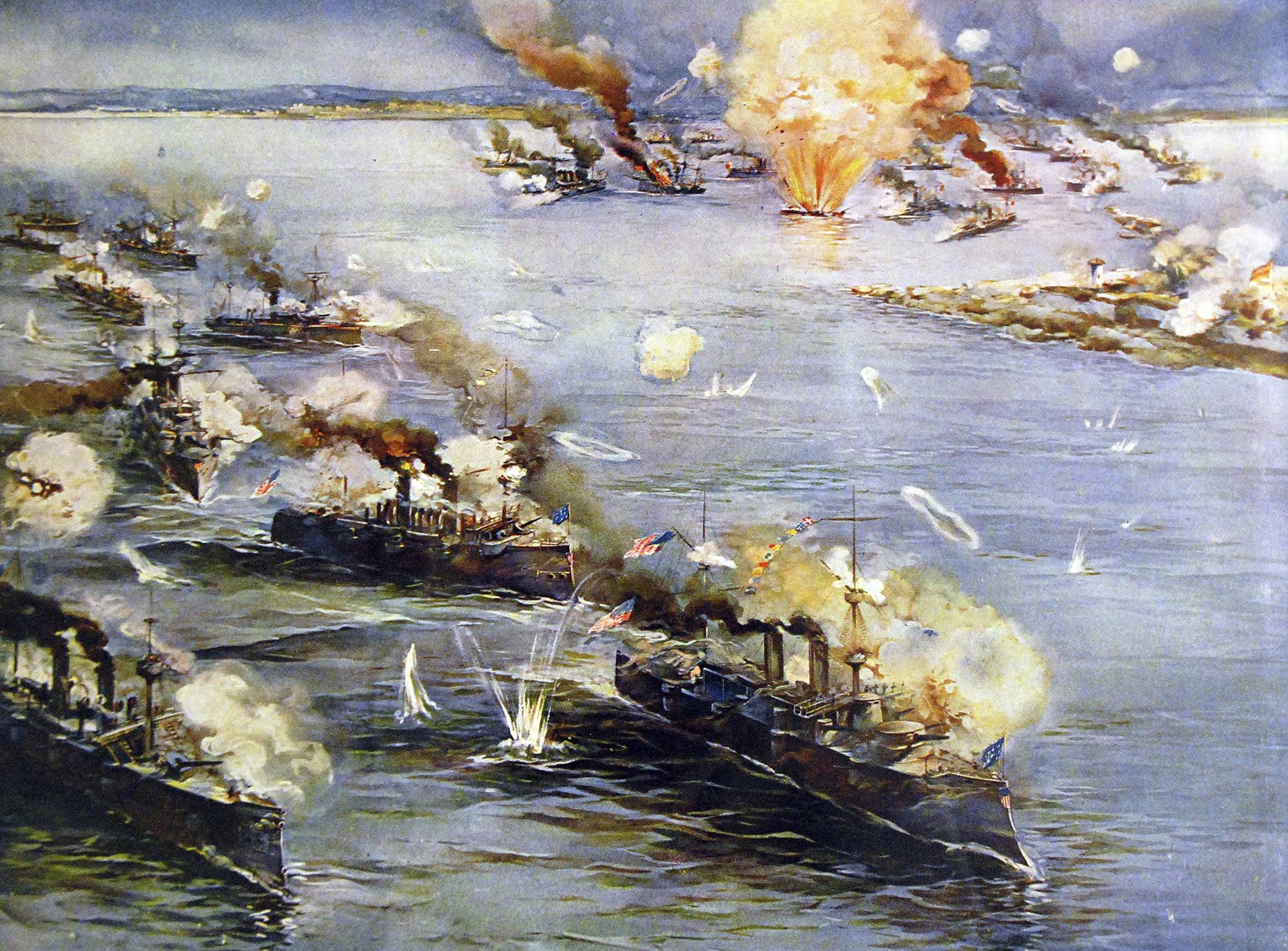

Dewey’s squadron was already in line and began an oval pattern, firing a broadside into the Spanish fleet. They then swung around and poured another broadside into the enemy. The Spanish returned fire, but it had little effect. They repeated the action four more times over two hours, devastating the Spanish and setting two of the ships on fire.

After the first round, Dewey withdrew to a safe distance and convened a meeting of his captains. With plenty of ammunition left and few injuries, the Americans stopped to have breakfast and then re-engaged the Spanish fleet. In the meantime, the Spanish pulled their ships into shallower to make themselves a smaller, more difficult target for the large U.S. ships. Dewey simply ordered his two gunboats into the bay to finish them off.

Montojo’s fleet was completely destroyed. Whatever wasn’t destroyed by the Americans was scuttled by the Spanish to keep them from being used by the enemy.

The U.S. ships then fired on the shore batteries and government offices, each of which quickly surrendered. The next day, Dewey landed a force of United States Marines at Cavite and finished off the shore positions.

The Outcome of the Battle

The Spanish suffered 77 killed and 271 wounded in the Battle of Manila Bay. Only nine Americans were wounded, and the Chief Engineer aboard the USGSC McCulloch died of a heart attack. A force of more than 10,000 soldiers under Army Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt would arrive to capture the Philippines by August 13, 1898.

Dewey’s victory was so complete that the aging, once-unknown sailor became a national celebrity back home. His face was plastered on everything from plates and bowls to ribbons and buttons. His men were awarded a special medal designed by Tiffany & Co. bearing Dewey’s likeness. Dewey was elevated to Admiral of the Navy in 1903, the only naval officer ever to hold the rank.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the battle of Manila Bay, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

0 Comments