The War of 1812 held a lot of meaning for the young United States. It was an assertion of its independence from Great Britain, a demand to be recognized and respected as a nation of the world, and it was a chance to show that the U.S. would assert itself militarily if the need arose.

What most people, even Americans, remember about the War of 1812 (aside from the burning of the White House) is that the conflict was fought to a draw. Very little tangibly changed following nearly three years of war – not a bad outcome for a young country fighting what was arguably the world’s greatest power at the time.

Background of The Battle of New Orleans

The real, lasting outcome of the war actually came after the war’s end: the Battle of New Orleans. Neither side knew that a peace treaty had been signed, but the battle was still important, as American determination and skill in combat forced the British to abide by the terms of the treaty.

It also ensured that New Orleans, Louisiana, and the rest of the Louisiana Territory remained in American hands.

Much of the American strategy during the war focused on Canada and capturing any parts of the British colony for the United States. To relieve the pressure on Canada, the British sent Maj. Gen. Sir Edward Pakenham and Adm. Sir Alexander Cochrane south to New Orleans.

Only the United States recognized the transfer of land from France to the U.S. under Napoleon. With Napoleon exiled to the island of Elba and the royalists in control of France, any territory the British captured in American Louisiana might not have been returned, even under the terms of the treaty that ended the War of 1812.

This would end U.S. governance of the territory and end its westward expansion.

Gen. Jackson Led His Ragtag Corps of Soldiers Against 8,000 Disciplined British Regulars

By Dec. 14, 1814, a fleet of 60 British warships carrying almost 8,000 men was anchored in the waters off the coast of Louisiana. They landed a vanguard of 1,800 men on the East Bank of the Mississippi River and attacked a plantation nine miles south of the city. While it might have seemed like a good idea at the time, it proved to be a harbinger of bad luck to come for the British.

Rather than advance on the city, the invading troops decided to stay at the plantation and await reinforcements. Its owner, an American officer named Maj. Gabriel Villere managed to escape before being captured and rode to Gen. Andrew Jackson. He warned of the British position and gave the Americans intelligence on the house.

In response, Jackson led a three-pronged assault on the unsuspecting British troops who had made camp for the night as they waited for more reinforcements. The American attack didn’t dislodge the British, but the number of casualties inflicted on the invaders informed the British that the Battle of New Orleans would be much more difficult than they expected.

Back in the city, Jackson had been preparing the defenses for weeks, bolstering American manpower with Tennessee militiamen, a force of regular army troops, a smattering of local civilian volunteers, and – famously – a force of pirates under Frenchman Jean LaFitte. They were given amnesty for their past crimes in exchange for their aid in the defense of the city.

By the time the British made their first reconnaissance in force, the American numbers had swelled to some 5,700. It might have looked grim to outsiders, but to Gen. Jackson, it was enough to write back home to his beloved Rachel that “all’s well.” It turns out that the first reconnaissance in force was the closest the British would get to taking the city, and they didn’t even know it.

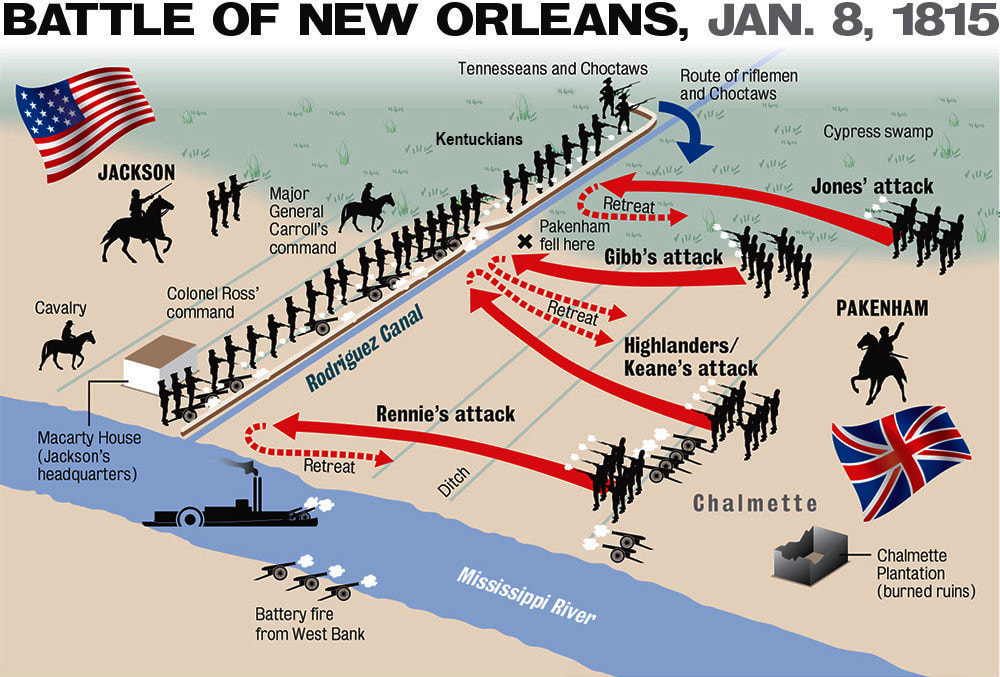

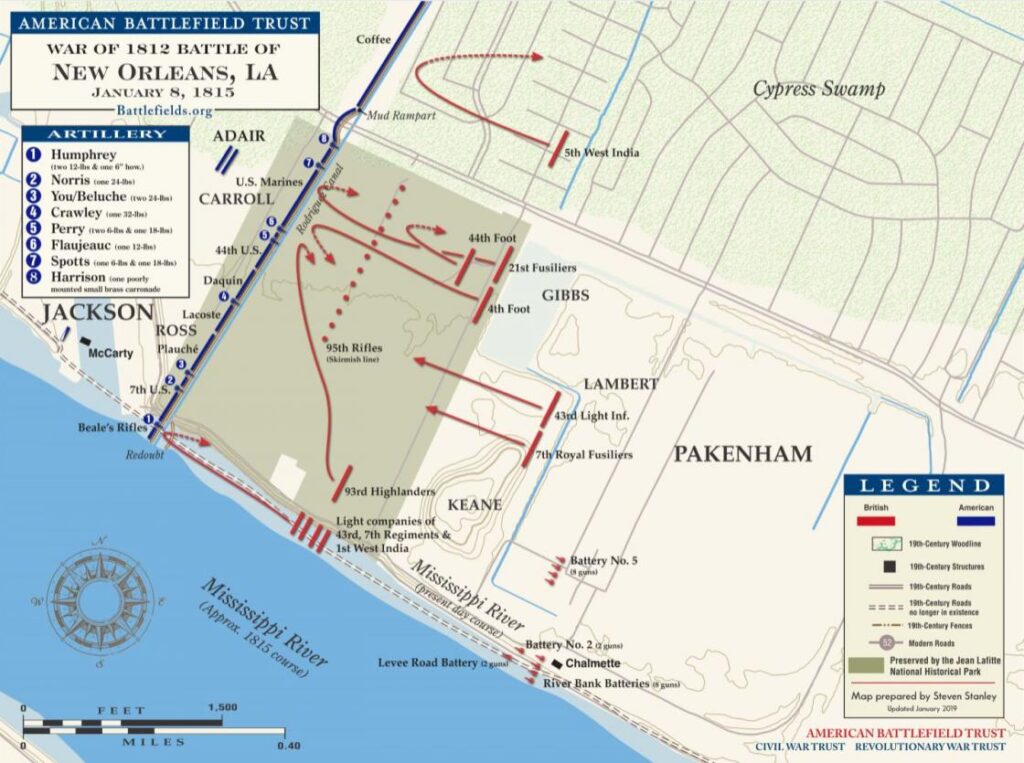

Jackson and the Americans had constructed a massive earthwork along a drainage canal that connected to the Mississippi River. What British Gen. Sir Edward Pakenham did next shows how much disdain they had for the American way of war. Despite having several possible avenues of attack that were less heavily defended, the British decided to have a go at the earthworks.

British Losses at the Battle of New Orleans

While attempting to probe these defenses, the right side of the American line nearly crumbled under the force of the British reconnaissance. As the Americans struggled to hold on to the right, the left side of the American defenses took all the notice. Cannons moved from U.S. Navy ships after being displaced by British warships, gunned down the redcoats attacking the left side in an enfilade.

The enfilading fire wreaked havoc on the British, and Packenham ordered a full retreat to determine their next course of action. During a war council, the British decided to assault the earthworks head-on once more rather than change their attack. At the same time, Jackson and the Americans added more guns to the line, ready for whatever came next.

When the British finally did attack in full force, it came on Jan. 8, 1815, more than two weeks after the War of 1812 ended and lasted about 30 minutes. It began with an exchange of cannon fire that saw the outgunned, but superior accuracy of the American guns knock out of five of seven British batteries.

The main assault saw a massed force of British troops out in the open attacking a reinforced and well-defended fortified position, still with guns positioned in enfilading fire. The worst part about the execution of the attack was that British field commanders forgot to bring the ladders and fascines needed to climb the walls, cross the canals, and make an effective attack.

British regular forces were sitting ducks, just taking fire from all sides and powerless to move forward. Maj. Gen. Packenham would be among the 291 British troops killed in the fighting, and a full one-fourth of the attacking British would become casualties. The Americans lost only 70 defenders, a miracle considering the force of veteran troops they were fighting against. The British were forced to move on and to abide by the terms of the Treaty of Ghent that ended the war. Most importantly, Louisiana remained firmly in American hands.

Excellent article. Thank you for writing.