The Battle of Wake Island was fought December 8-23, 1941, during the opening days of World War II. A tiny atoll in the central Pacific Ocean, Wake Island was annexed by the United States in 1899. Located between Midway and Guam, the island was not permanently settled until 1935 when Pan American Airways built a town and hotel to service their trans-Pacific China Clipper flights. Consisting of three small islets, Wake, Peale, and Wilkes, Wake Island was to the north of the Japanese-held Marshall Islands and east of Guam.

As tensions with Japan rose in the late 1930s, the U.S. Navy began efforts to fortify the island. Work on an airfield and defensive positions began in January 1941. The following month, as part of Executive Order 8682, the Wake Island Naval Defensive Sea Area was created which limited maritime traffic around the island to U.S. military vessels and those approved by the Secretary of the Navy. An accompanying Wake Island Naval Airspace Reservation was also established over the atoll. Additionally, six 5-guns, which had previously been mounted on USS Texas (BB-35), and twelve three anti-aircraft guns were shipped to Wake Island to bolster the atoll’s defenses.

Preparing the Marines for the Battle of Wake

While work progressed, the 400 men of the 1st Marine Defense Battalion arrived on August 19, led by Major James P.S. Devereux. On November 28, Commander Winfield S. Cunningham, a naval aviator, arrived to assume overall command of the island’s garrison. These forces joined the 1,221 workers from the Morrison-Knudsen Corporation which were completing the island’s facilities and the Pan American staff which included 45 Chamorros (Micronesians from Guam).

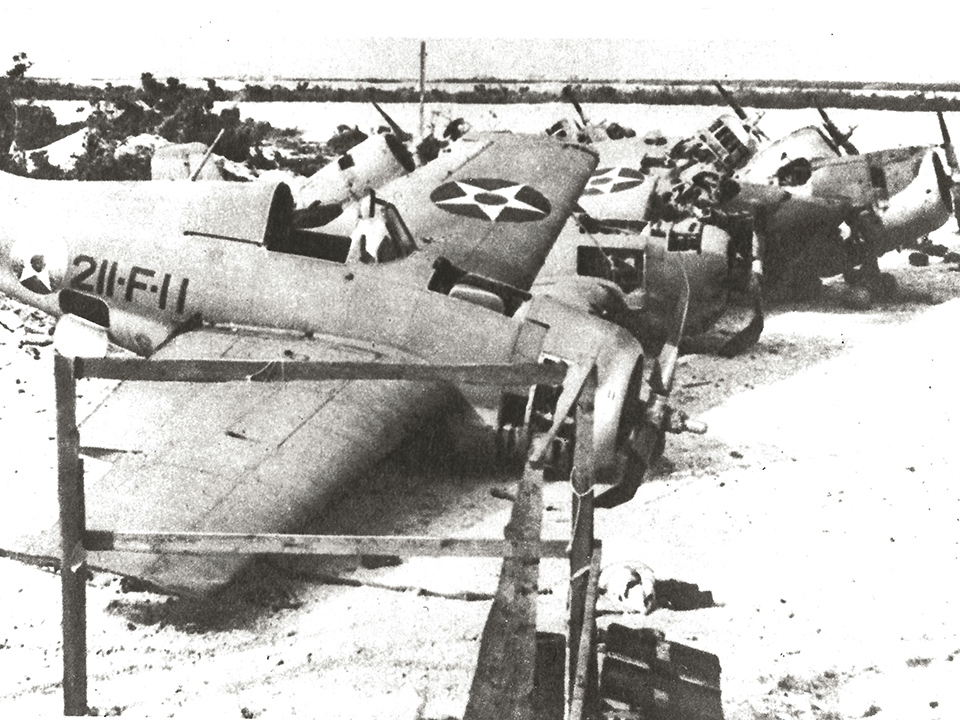

By early December the airfield was operational, though not complete. The island’s radar equipment remained at Pearl Harbor and protective revetments had not been built to protect aircraft from aerial attack. Though the guns had been emplaced, only one director was available for the anti-aircraft batteries. On December 4, twelve F4F Wildcats from VMF-211 arrived on the island after being carried west by USS Enterprise (CV-6). Commanded by Major Paul A. Putnam, the squadron was only on Wake Island for four days before the war began.

The Japanese Attack Begins

Due to the island’s strategic location, the Japanese made provisions to attack and seize Wake as part of their opening moves against the United States. On December 8th, as Japanese aircraft were attacking Pearl Harbor (Wake Island is on the other side of the International Date Line), 36 Mitsubishi G3M medium bombers departed the Marshall Islands for Wake Island. Alerted to the Pearl Harbor attack at 6:50 AM and lacking radar, Cunningham ordered four Wildcats to begin patrolling the skies around the island. Flying in poor visibility, the pilots failed to spot the inbound Japanese bombers.

Striking the island, the Japanese managed to destroy eight of VMF-211’s Wildcats on the ground as well as inflicted damage on the airfield and Pam Am facilities. Among the casualties were 23 killed and 11 wounded from VMF-211 including many of the squadron’s mechanics. After the raid, the non-Chamorro Pan American employees were evacuated from Wake Island aboard the Martin 130 Philippine Clipper which had survived the attack.

A Stiff Defense Against of the Japanese Aircraft

Retiring with no losses, the Japanese aircraft returned the next day. This raid targeted Wake Island’s infrastructure and resulted in the destruction of the hospital and Pan American’s aviation facilities. Attacking the bombers, VMF-211’s four remaining fighters succeeded in downing two Japanese planes. As the air battle raged, Rear Admiral Sadamichi Kajioka departed Roi in the Marshall Islands with a small invasion fleet on December 9. On the 10th, Japanese planes attacked targets in Wilkes and detonated a supply of dynamite which destroyed the ammunition for the island’s guns.

Arriving off Wake Island on December 11th, Kajioka ordered his ships forward to land 450 Special Naval Landing Force troops. Under the guidance of Devereux, Marine gunners held their fire until the Japanese were within range of Wake’s 5″ coastal defense guns. Opening fire, his gunners succeeded in sinking the destroyer Hayate and badly damaging Kajioka’s flagship, the light cruiser Yubari. Under heavy fire, Kajioka elected to withdraw out of range. Counterattacking, VMF-211’s four remaining aircraft succeeded in sinking the destroyer Kisaragi when a bomb landed in the ship’s depth charge racks.

Captain Henry T. Elrod posthumously received the Medal of Honor for his part in the vessel’s destruction.

While the Japanese regrouped, Cunningham and Devereux called for aid from Hawaii. Stymied in his attempts to take the island, Kajioka remained nearby and directed additional air raids against the defenses. In addition, he was reinforced by additional ships, including the carriers Soryu and Hiryu which were diverted south from the retiring Pearl Harbor attack force. While Kajioka planned his next move, Vice Admiral William S. Pye, the Acting Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, directed Rear Admirals, Frank J. Fletcher and Wilson Brown, to take a relief force to Wake.

Centered on the carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) Fletcher’s force carried additional troops and aircraft for the beleaguered garrison. Moving slowly, the relief force was recalled by Pye on December 22 after he learned that two Japanese carriers were operating in the area. That same day, VMF-211 lost two aircraft. On December 23, with the carrier providing air cover, Kajioka again moved forward. Following a preliminary bombardment, the Japanese landed on the island. Though Patrol Boat No. 32 and Patrol Boat No. 33 were lost in the fighting, by dawn over 1,000 men had come ashore.

The Final Step of the Battle of Wake

Pushed out of the southern arm of the island, American forces mounted a tenacious defense despite being outnumbered two-to-one. Fighting through the morning, Cunningham and Devereux were forced to surrender the island that afternoon. During their fifteen-day defense, the garrison at Wake Island sank four Japanese warships and severely damaged a fifth. In addition, as many as 21 Japanese aircraft were downed along with a total of around 820 killed and approximately 300 wounded. American losses numbered 12 aircraft, 119 killed, and 50 wounded.

Aftermath The Battle of Wake

Of those who surrendered at the the Battle of Wake, 368 were Marines, 60 US Navy, 5 US Army, and 1,104 civilian contractors. As the Japanese occupied Wake, the majority of prisoners were transported from the island, though 98 were kept as forced laborers.

While American forces never attempted to re-capture the island during the war, a submarine blockade was imposed which starved the defenders. On October 5, 1943, aircraft from USS Yorktown (CV-10) struck the island. Fearing an imminent invasion, the garrison commander, Rear Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara, ordered the execution of the remaining prisoners.

This was carried out on the northern end of the island on October 7th, though one prisoner escaped and carved 98 US PW 5-10-43 on a large rock near the killed POWs’ mass grave. This prisoner was subsequently re-captured and personally executed by Sakaibara. The island was re-occupied by American forces on September 4, 1945, shortly after the war’s end. Sakaibara was later convicted of war crimes for his actions on Wake Island and hung on June 18, 1947.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the Battle Of Wake Island, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

Nice article but unfortunately, it begins with a historically incorrect photo at the top, of a Naval aircraft (likely an Avenger), from much later in WWII.

Recommend that photo be replaced with one of a USMC F4F Wildcat with the correct national insignia from December 1941, which still had a red circle depicted in the center of the star.

I served in the Navy from 1965 to 1967 on the USS Philip DD498 out of Pearl Harbor. WestPac in 1966. After the Navy I worked for Morrison Knudsen Corp of Boise, ID where I learned of MK’s involvement in the Pacific construction projects. One of a consortium of a company called Six Companies. While on business travel I met one of the MK survivors of Wake and he invited me to a Wake Island survivors reunion being held in Boise. For 3 days (and nights) I attended the reunion and met many of the MK and Marine vets attending. Many stories were told of which I treasure. This is the first article that accurately represents the MK civilian workforce some of whom fought alongside the Marines. And of those left guys left behind to complete the project and who were executed after it’s completion. The Japanese decided it would be less expensive to execute than transport to one of their prisoner of war camps. Thank you for printing this article.