The Continental Army was camped for the 1777-78 winter at Valley Forge, twenty miles from Philadelphia, the British-occupied American capital. At least a third of the eleven thousand men were without shoes, coats, and blankets to protect them from the constant rain. They suffered from exposure, typhus, dysentery, and pneumonia. Food was running out. Men were starving, dying, the desertion rate was escalating, and the States could not meet their enlistment quotas. Able-bodied men were simply not willing to fight. Able-bodied white men, that is. As they waited out the winter, General Washington had no plan to replace his dwindling manpower.

Rhode Island general James Varnum, who commanded the 1st Rhode Island Regiment at the outset of the war, offered a solution that would not sit well with Washington. Combine Rhode Island’s two depleted regiments into a single formation and send the extra officers home to recruit a new unit consisting of both slaves and free men.

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment at the Beginning of the American Revolutionary War

In the early days of the American Revolutionary War, free black men were serving, and slaves served in place of the men who ‘owned’ them. In many cases, their enlistment bonuses or even their pay went straight to their ‘masters.’ Even so, it was known that they fought bravely at Lexington and Concord and at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Perhaps because he was a prominent Virginia plantation owner and slaveholder, this information did not sufficiently impress the General. Soon after he was appointed Commander-in-Chief, Gen. Washington signed an order forbidding all black men’s recruitment.

At the outset of the war, he spoke against using black freemen and slaves as soldiers, fearing armed slaves would lead to an armed slave rebellion. But by 1778, things had changed. After intense pressure from the Continental Congress and some of his own Officers, Washington grudgingly agreed to enlist black soldiers into the Continental Army to defend Rhode Island’s colony from the British occupying force. Col. Christopher Greene would remain as the commander of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment.

In February 1778, Rhode Island Gov. Nicholas Cooke and his legislature overrode slaveholders’ objections and passed The Slave Enlistment Act. The law allowed “every able-bodied negro, mulatto, or Indian man slave in this state to enlist as regular soldiers into either of the Continental Battalions being raised.” The law also included the promise that any man, even a slave, who chose to enlist, would be freed on their acceptance into the unit and completion of military service. Slave owners were promised ‘compensation for the market value of the individual slave recruits.’

The new law had little effect on public opinion or white male enlistment, for that matter. However, the British expeditionary forces and several Hessian regiments of foot soldiers had been an occupying force in Newport, Rhode Island, since December 1776. Over the next couple of years, their suppression of trade and forays against the rest of the colony, including their later occupation of Aquidneck Island, was the source of increasing anger, hardship, and frustration among the general public.

One of the recruiting officers, Capt. Elijah Lewis reported that local whites were warning slaves that those who enlisted would be given the most dangerous assignments and that if taken prisoner, they would be shipped off “to the West Indies and sold as slaves,” and sacrificed in battle by being used as breastworks. To be clear, using men as breastworks meant that these soldiers would face certain death serving as unarmed human shields for the white Continental Infantry soldiers.

The six members of the General Assembly who voted against the law issued a formal protest. They argued there was an insufficient number of black men in the state with an inclination to enlist, that the measure would be too expensive, that slaveholders would not be satisfied with the amount of compensation, and that raising a unit of slaves was inconsistent with the principles of liberty that the United States was fighting for.

The majority of support from the General Assembly was short-lived. In a statewide election held in April 1778, Rhode Island voters demonstrated their discontent by replacing over half of their legislators. One of the first acts of the new administration was to repeal the controversial law. A new edict issued in May declared that the freeing of slaves for military service had only been temporary and that after June 10, “no negro, mulatto and Indian slave, be permitted to enlist into said battalions.”

Yet during the months that the Slave Enlistment Act was in effect, Col. Greene and his fellow officers recruited over one hundred forty men who were slaves or freed black men. Many had no prior experience handling muskets or other weapons, but their commanding officers decided they were battle-ready after six weeks of training.

The Black Regiment Saw its First Combat at the Battle

On August 28, 1778, The Regiment saw its first combat at the Battle of Rhode Island. With a garrison of six thousand British and Hessian soldiers, the British army had secured a first-rate port and a strategic base to support its grand plan to split the northern colonies at the Hudson River and subdue an isolated New England.

The Continental Army was in retreat as the British tried to trap them in New England. General John Sullivan, whose command included the First Rhode Island, ordered the men to take up positions on the hillsides around Portsmouth, located on Aquidneck Island.

The British sent ships river to bombard the First. The assault from the river continued for hours as more British troops attacked the Continentals from the ground. Weather conditions stopped the expected support for the Continentals by newly arrived French naval forces. Finally, the British command sent in one of its most feared Hessian mercenary units, the Anspach Regiment.

The Hessians repeatedly attacked, but the First Rhode Island held their ground against a force of four thousand professional German soldiers. As night fell, the Hessians made a push that broke portions of the Continental line. The men of the 1st Rhode Island under Col. Greene held their line against three assaults by British and Hessian troops on the west flank. The courageous fighting by the First allowed the remainder of the Continental Army to escape the British and regroup. The British had failed to overwhelm the American force.

While the battle was considered a defeat for Continental forces under General John Sullivan, the Black Regiment’s performance prevented a complete rout. In his 1859 History of the State of Rhode Island, historian Samuel Greene Arnold reported that the regiment: “distinguished itself in deeds of desperate valor. Posted behind a thicket in the valley, three times, they drove back the Hessians, who repeatedly charged down the hill to dislodge them.”

Aquidneck Island remained in British hands for the time being. Still, thanks especially to Col. Christopher Greene’s troops’ heroic efforts, Gen. Sullivan was able to complete an orderly withdrawal of his 5,000-man force to Bristol, RI, and Tiverton RI.

On September 15, 1778, the New Hampshire Gazette reported the retreat was made “in perfect order and safety, not leaving behind the smallest article of provision, camp equipage or military stores.”

In 1781, Colonel Greene and many of his black soldiers were killed in a skirmish with American loyalists; Greene’s body was reported mutilated. Many believed this was punishment for having led black soldiers.

As troop strength in General Washington’s Continental Army diminished, the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island Regiments were joined to form The Rhode Island Regiment participated at the Battle of Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781. It was the engagement that led to the British surrender and the end of the American Revolution. At Cornwallis’s capitulation, the freemen and soon-to-be-freed slaves stood at attention alongside all the other Continental regiments – from Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia – and took the salute of the enemy, which until recently had almost destroyed them.

The colonies had won their independence. White soldiers were granted land and a pension. Black soldiers who had been slaves were granted their freedom. According to one historian, the discharged troops were “dumped back into civilian society,” with only the white soldiers being guaranteed the one hundred acres of bounty land from the Federal Government, as well as a pension.

Gen. Varnum and another white officer from the regiment, Col. Olney, campaigned unsuccessfully on their behalf. In 1794, thirteen of the veterans hired Samuel Emory to present their claims to the War Department in Washington. In 1818, the Black Regiment veterans were finally granted Federal pensions, as were all veterans who could prove their service.

Several black veterans of the Rhode Island Regiment are known to history. Ichabod Northup was born a slave around 1745. He enlisted in the 1st Rhode Island in 1778 and served as a fifer. Northrup was among those serving at Croton, New York, when Col. Christopher Greene was killed. Northrup was captured, threatened with hanging for not divulging troop movements to the enemy, and spent the remainder of the war as a prisoner.

He returned after the war to East Greenwich, purchasing a house that still stands on Division Street. In 1820 he testified that he relied on charity, was unable to work – his toes having frozen in the war, was “impoverished, could not support himself,” and his house was “much out of repair.”

Based on some five years of service, he was granted a pension under an Act of Congress. He would have been seventy-three years old.

In 1792, Congress passed legislation that limited military service only to “free, able-bodied, white male citizens.”

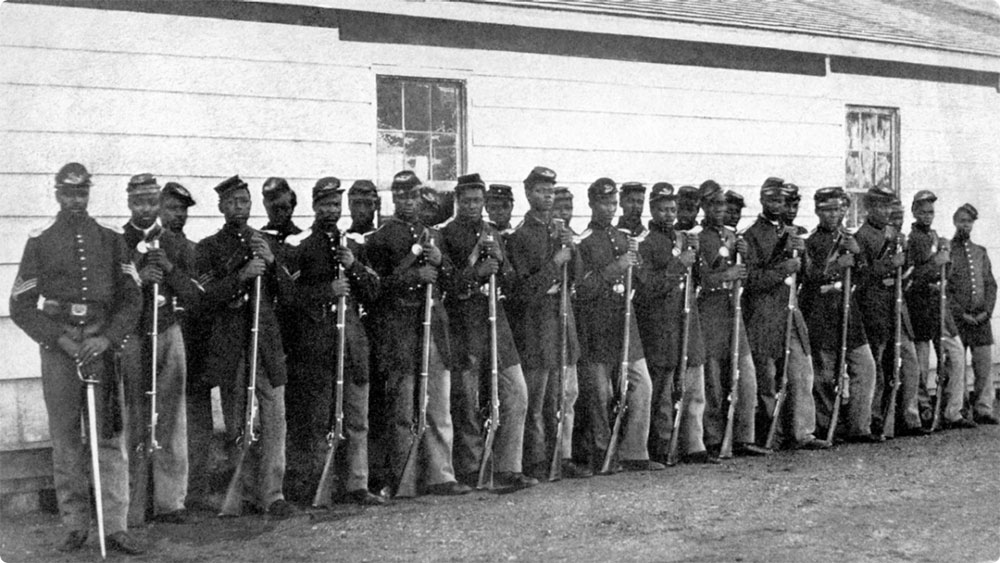

The photo presented at the beginning is from the Civil War, not the revolutionary one.

One of my Great #5Grandfathers fought with the First in Rhode Island. Jabez (Jabin) Remington. TY🖤❤️