Former dog sentry handler Richard Cunningham shared a history about well-trained dogs as a new kind of warfare. In the Vietnam War about 350 dogs were killed in action and 263 handlers were killed. When U.S. forces exited from Vietnam only 200 of the dogs made it back to the states.

“I would wager that 90 percent of American combat troops killed in action during the Vietnam War never saw their killers. Whether it was a sniper at 200 yards, a rocket fired into a base camp or an attack from a well-concealed bunker complex, the element of surprise was usually on the side of our enemies. But our forces did have one elite weapon that sometimes took the advantage away. At times, these weapons even turned such situations upside down and enabled us to surprise and take them out.

That elite weapon were our military working dogs in Vietnam War, and we had thousands of them.

Military Working Dogs Were the Elite Weapon in the Vietnam War

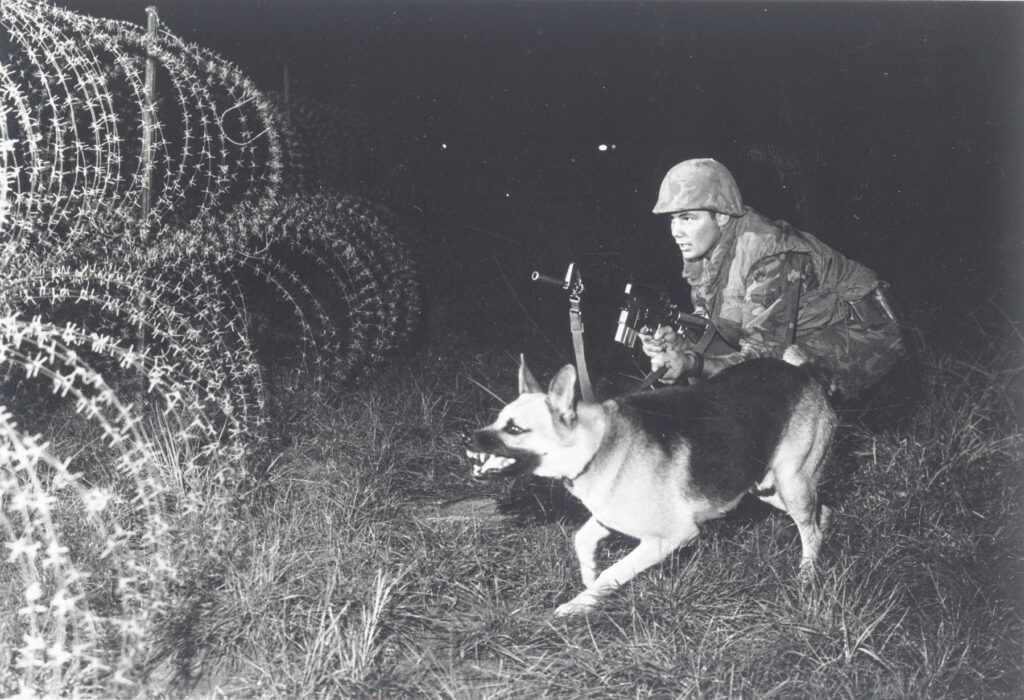

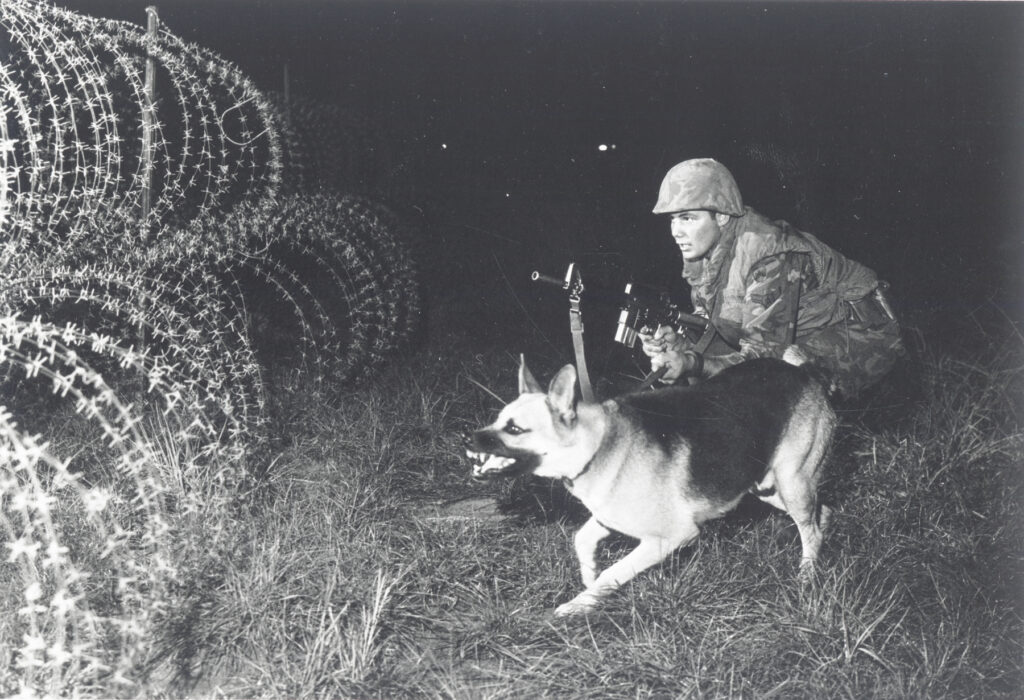

I was a sentry dog handler in Vietnam from 1967 to 1968, a member of the 212th Military Police Sentry Dog Company stationed in Tay Ninh. My companion was a German shepherd named Smokey. I was 20 years old and weighed 135 pounds; Smokey weighed 90 pounds. Our unit’s responsibility was to protect the Tay Ninh Base Camp, and especially the ammunition dump. Smokey and I typically worked at night, 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., but we would also conduct daylight area sweeps when temporarily attached to infantry units.

In Vietnam, American forces used dogs for everything from base security to detecting ambushes to hunting down fleeing enemy units. We used German shepherds like Smokey, mixes of shepherd types, and Labrador retrievers that were well trained in detecting, attacking, and tracking the enemy. They were certainly not all purebreds. Most were given to the military by families back home.

The dogs started out at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas with a thorough physical exam. Then they were observed and tested to determine which area of training they would be assigned. Aggressive dogs usually went to the sentry unit. Less aggressive but still highly intelligent shepherd dogs went to the scout school. The Labradors, with their amazing noses, went straight to tracker training. Every dog accepted was highly intelligent, and each became a canine soldier, with his or her own individual four-digit service number tattooed in the left ear.

Dogs and their handlers went through three phases of instruction: drill/obedience, aggression, and scouting. And although it appeared that the dogs were being instructed, it was the soldiers who were actually being taught. At Okinawa, where I met and trained with Smokey, most of the dogs were veterans being reassigned to new handlers. They knew the drills inside and out, and we did not. Our training instructors seemed to take a perverse pleasure in informing us how dumb we were compared with the dogs.

Every dog responded to both verbal and nonverbal hand commands. They loved to work purely for the approval and praise of their handler and partner. And throughout training that special bond was formed between trooper and dog. I know I felt it with Smokey.

Handlers and Their Scout Dogs in the Vietnam War

Once in Vietnam, these dogs were the gold standard. Search-and-destroy missions used a handler and his scout dog to walk point, out in the jungle, able to raise an alarm about an ambush long before most of the unit was in danger. The dog’s handler could determine the distance to the danger, usually by the degree of his dog’s state of “alert.” Then, instead of walking into the Vietcong trap, he could call in fire or air support to obliterate the enemy position. Not every unit on patrol got a dog; there weren’t enough to go around, and in those cases, a Soldier would have to walk point alone. But with a scout dog team leading the way, most patrols were successful or uneventful.

A human nose has about five million scent receptors; a shepherd has at least 225 million. The dogs can detect movement much faster and more accurately than we can, and their ears can hear, even at a very early age, sound from four times farther away than we can. What’s more, all our dogs had lived with our American “smells” for years. The scent of the Vietnamese was very different and much easier for them to pick up and alert on.

This scent or sound alert was also true of the sentry dog teams, like Smokey and me. When a dog team arrived at its post – usually just a path around a camp, ammo dump, or airfield – it performed a “changeover.” The handler changed the dog’s choke-chain collar to his leather “now it’s time to work” collar. The dog understood the difference immediately and went to work.

There were also mine and booby trap dogs. They protected our soldiers on patrol from the many and diverse devices set to kill and maim. Take the thin, monofilament lines that were practically invisible to the human eye, which the Vietcong attached to a grenade or other explosive device that detonated when “tripped.” A large proportion of American infantry casualties were caused by these devastating devices. But a trained dog could detect the trap, and it would be neutralized.

Combat tracker teams consisted of five soldiers and two Labrador retrievers. Each team included a visual tracker and a dog handler upfront, followed by their cover man, then the radioman and the team leader. Expertly trained by New Zealand’s elite Special Air Service in Malaysia, their dogs were initially provided by the British military. These teams didn’t wait to be ambushed. They chased down the Vietcong and the North Vietnamese Army forces after a firefight when they would attempt to disappear back into the jungle.

Throughout the course of the war, 4,000 dogs served in Vietnam and Thailand. It was well known that the enemy put a bounty on both the handlers and their dogs. Approximately 350 dogs were killed in action, many more were wounded, and 263 handlers were killed.

When our politicians decided to exit Vietnam – in a hurry – the military classified our dogs as “equipment.” As such, they were left behind. Some, but not many, were transferred to the South Vietnamese military and police. Of the 4,000 dogs that served in-country, fewer than 200 made it back to the States. Not a pleasant thought to consider given their incredible service, endurance, and devotion to duty.

I’ve heard it said that without our military dogs, there would be 10,000 additional names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall. I, for one, think that’s an understatement.”

Richard Cunningham served as a sentry dog handler in Vietnam and later worked with the New York Police Department and as a fraud investigator.

My father Dr Robert S Leverton, served in Vietnam and his dog was Tanda. Understandably, He doesn’t like to talk about it very much, but he loved Tanda. Thank you for writing this article!

My tour in 69/70 encountered a few dogs. They were truly responsive to their handlers commands. They saved lots of lives.

My unit in Pleiku (1969) inherited a large Shepherd because we had a fenced-in compound. I don’t know what happened to his former handler–I only know when I volunteered to give him some exercise, he took ME for a walk, through the brush, menacing every mamasan on the base. I hope he lived to come home.

I was an Army Sentry Dog handler 1968-69. my dog’s name was Watch-boy. He was a great dog. We spent most of our time at Long Binh, and a few months at Vung Tau. Watch boy was extremely aggressive so we were selected for the Demo team at Long Binh. The Sentry Dog Demo team at Long Binh was used for dog and pony shows for VIPs/visitors who were in-country to see how the war was going I suppose. Overall I had a pretty good tour. Nothing major occurred. Occasional rocket and mortar attacks nothing near me, but at19-20 years old those were kind of big adventures. also, at that age you think you are going to live forever.

It should be noted that even though we were told at the Military Police school (Fort Gordon) becoming a dog handler was voluntary in my case it definitely was not voluntary. I was assigned, I did not volunteer. The reason I did not volunteer was they told us that as dog handlers our first duty station would be Vietnam. This was in July 1968 right after TET. From all I had seen about TET and Vietnam on the news that was the last place I wanted to go. In those days I was still dumb enough to believe I might be stationed in Hawaii after all that was one of the places I chose on my (dream) list of places I would like to be assigned when I joined the Army. Nowhere on my dream list did I have Vietnam. I am glad I did it, made some great friends, had some interesting experiences.

I would do it all over again in a minute. I didn’t understand the politics of the war. I didn’t give a damn about the war protestors or draft dodging freaks in the street wanting to bring me home. I wanted to do my time, serve my country and get home in one piece. That is the way I was raised if called, you served in the military(honorably).

While I am on a bit of a rant. I keep hearing stories from Vietnam veterans telling how they were physically and verbally abused by people who recognized that they were soldiers returning from Vietnam. Some even said they went home in civilian clothes. When I came home from Vietnam, I came through California. I flew out of San Francisco to Dallas Texas, then to Memphis Tennessee, and home to Muscle Shoals, Alabama. I wore my uniform all the way and I was proud of it. I didn’t have any problems at all, and for damn sure nobody spit on me or my uniform or I would probably still be in prison. I was treated with respect and dignity and a few compliments on my way home. There was nothing negative said or done to me.

For the guys who are telling those kinds of stories; shame on you for putting up with it. If it happened and you didn’t do something about it you should be ashamed to tell it.

If I sound like a “lifer” I am not. I did 3 years and got out. I graduated from college had a great career and a great life. Vietnam does not define me. It was something that I did, and something I am proud of. I don’t wear the Vietnam paraphernalia hats/vests or any of that. I don’t have a problem with those who do. it’s just not my thing.

I will add this: next to my family the Army is the best thing that ever happened to me. Those 3 years opened so many doors for me and provided so many opportunities that I could never have imagined. I will always be grateful that I served. It should be noted that I didn’t go into the Army willingly. I was drafted. When I arrived at the induction center, I found that I could have a modicum of influence on my (short) military career by signing up for an extra year which I did.

Is there a way to determine what happened a dog donated to Air Force in 1969/70?

We know he went to Lachlund AFB and was “loved and tested well”

I served in Nam for 2.5 years. Volunteered for sentry dog duty knowing I was going to Nam. I just wanted to be with a dog. His name was Prince, he was 11 months old so we were both learning how to perform our duty together on Okinawa. The reason one of the reasons I stayed in Nam so long was because of Prince. We were in Tuy HOA, ankhe and Pleiku. Had a great bond with him. Hardest thing I had have ever done was my last day In Nam was feeding him and petting him and walking away. Makes me cry every time I think about it.

Is there a way to determine what happened to a dog donated to Air Force in 1969/70?

We know he went to Lachlund AFB and was “loved and tested well”

I owe everything to a shepherd named Gary. Because of him my Dad and many other men came home from Vietnam.

I owe everything to a shepherd named Gary. Because of him my Dad and many other men came home from Vietnam.