From July 1 to July 3, 1863, the invading forces of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army clashed with the Army of the Potomac under its newly appointed leader, General George G. Meade at Gettysburg, some 35 miles southwest of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Casualties were high on both sides: Out of roughly 170,000 Union and Confederate soldiers, there were 23,000 Union and 28,000 Confederate casualties; more than one-quarter of the Union army’s effective forces and more than a third of Lee’s army were killed, wounded or missing.

The Gettysburg Address Began as Lincoln’s Invitation

After three days of battle, Lee retreated towards Virginia on the night of July 4. It was not only a crushing defeat for the Confederacy, but the battle also proved to be the turning point of the war: Gen. Robert E. Lee’s defeat and retreat from Gettysburg marked the last Confederate invasion of Northern territory, and the beginning of the Southern army’s ultimate decline.

As had become customary following previous mass-casualty battles, thousands of Union soldiers killed at Gettysburg were quickly buried, many in poorly marked graves. In the months that followed, however, local attorney David Wills spearheaded efforts to create a national cemetery at Gettysburg. Wills and the Gettysburg Cemetery Commission originally set October 23, 1863, as the date for the cemetery’s dedication, but delayed it to mid-November after their choice for speaker, Edward Everett, said he needed more time to prepare. Everett, the former president of Harvard College, former U.S. senator and former secretary of state, was at the time one of the country’s leading orators.

Almost as an afterthought, Wills also sent a letter to President Abraham Lincoln – just two weeks before the ceremony – requesting “a few appropriate remarks” to consecrate the grounds at the official dedication ceremony for the National Cemetery of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania; remarks which became famously known world-wide as the Gettysburg Address.

The Gettysburg Address Redefined the Civil War

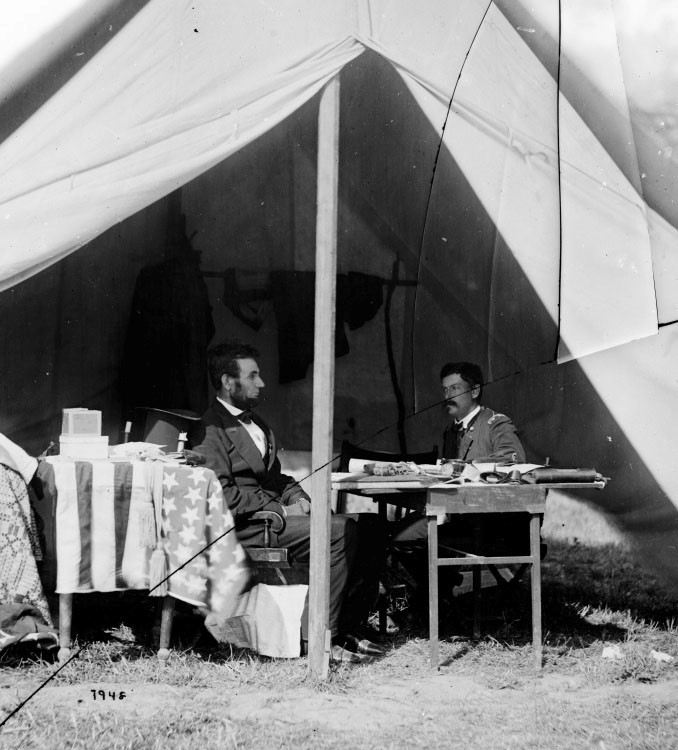

When he received the invitation to make the remarks at Gettysburg, Lincoln saw an opportunity to make a broad statement to the American people on the enormous significance of the war, and he prepared carefully. Though long-running popular legend holds that he wrote the speech on the train while traveling to Pennsylvania, he probably wrote about half of it before leaving the White House on November 18th and completed writing and revising it that night, after talking with Secretary of State William H. Seward, who accompanied him to Gettysburg.

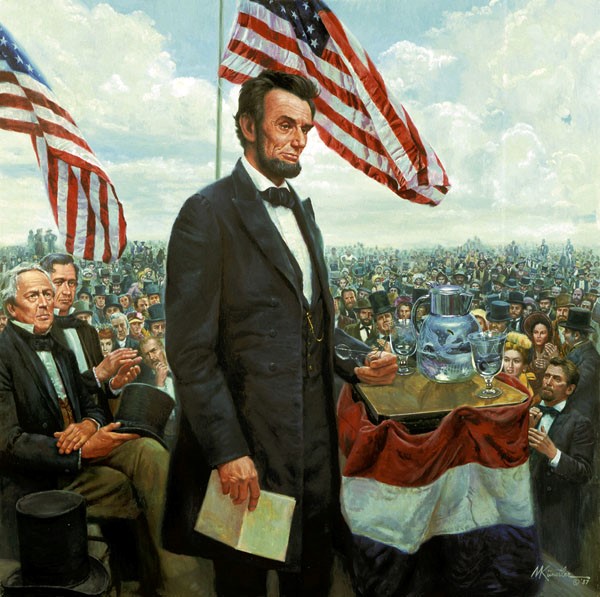

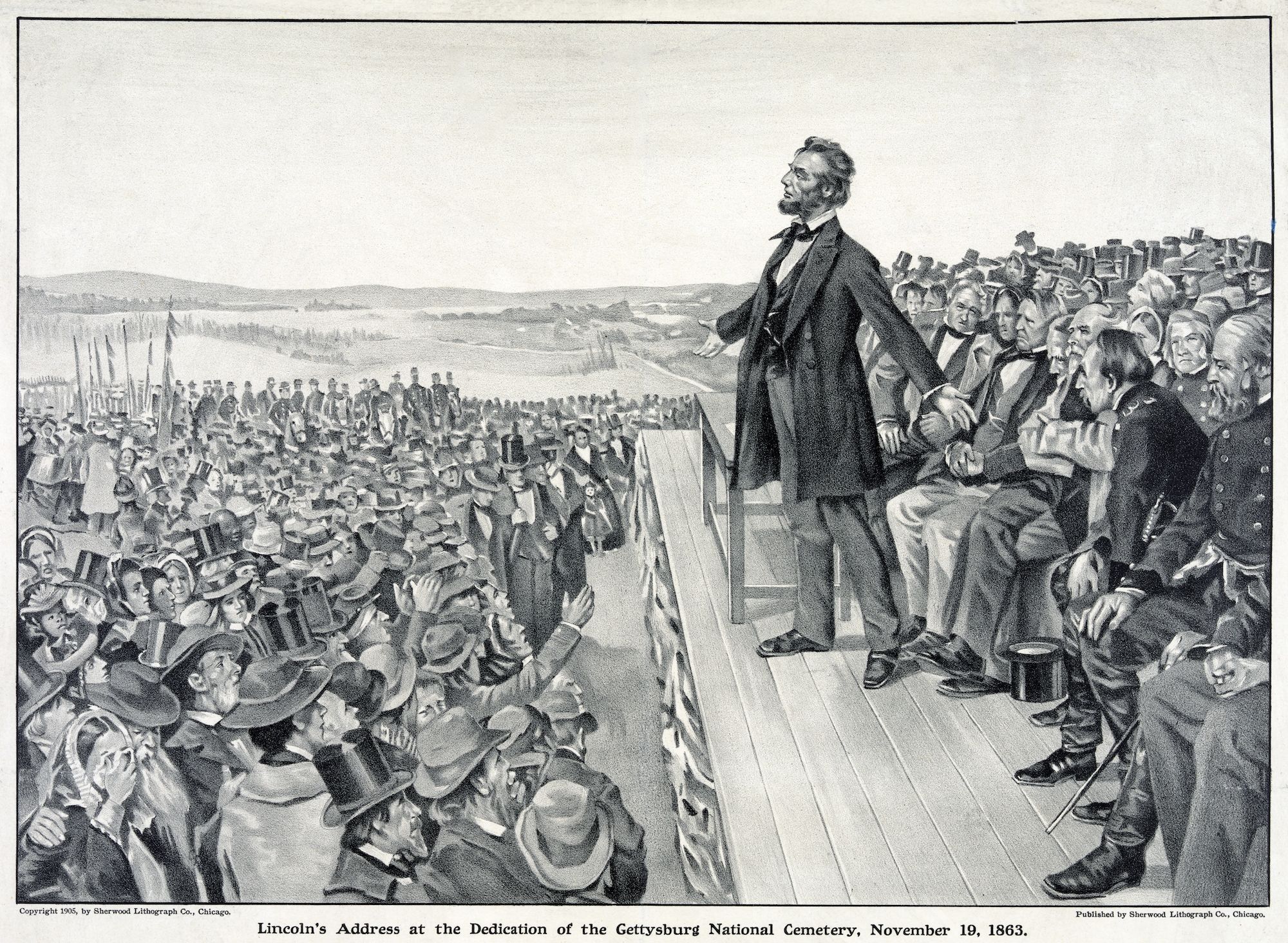

On the morning of November 19, Everett delivered his two-hour oration (from memory) on the Battle of Gettysburg and its significance, and the orchestra played a hymn composed for the occasion by B.B. French. Lincoln then rose to the podium and addressed the crowd of some 15,000 people. He spoke for less than two minutes, and the entire speech was only 273 words long. Beginning by invoking the image of the founding fathers and the new nation, Lincoln eloquently expressed his redefined belief that the Civil War was not just a fight to save the Union, but a struggle for freedom and equality for all, an idea Lincoln had not championed in the years leading up to the war.

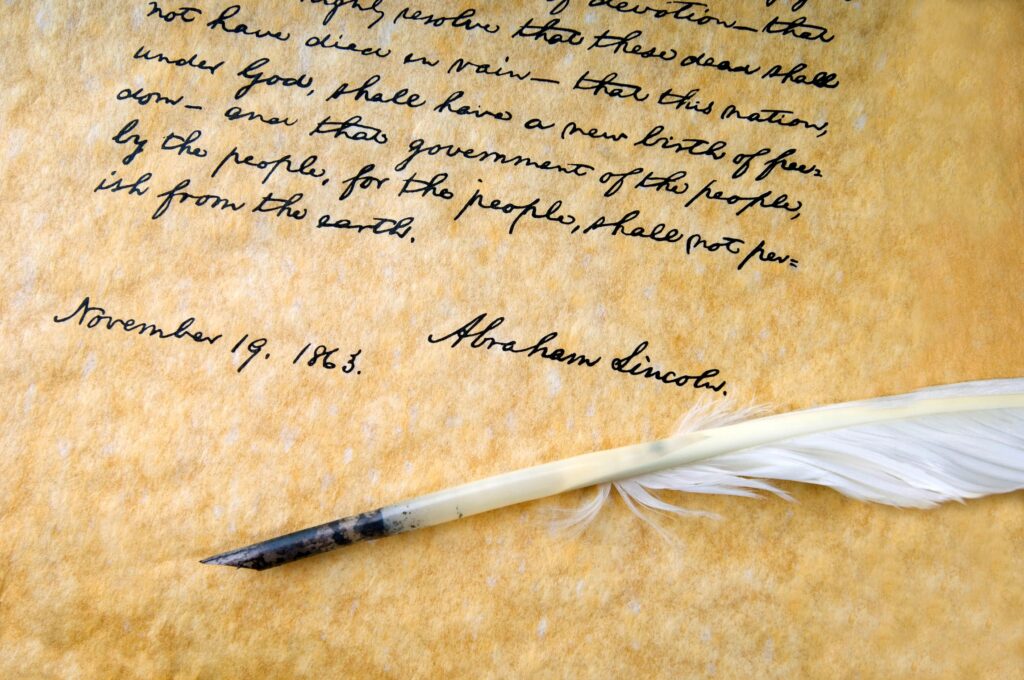

This was his stirring conclusion: “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The Gettysburg Address Elevated Equality and Democracy

The essential themes and even some of the language of the Gettysburg Address were not new; Lincoln himself, in his July 1861 message to Congress, had referred to the United States as “a democracy – a government of the people, by the same people.” The radical aspect of the speech, however, began with Lincoln’s assertion that the Declaration of Independence – and not the Constitution – was the true expression of the founding fathers’ intentions for their new nation. At that time, many white slave owners had declared themselves to be “true” Americans, pointing to the fact that the Constitution did not prohibit slavery; according to Lincoln, the nation formed in 1776 was “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” In an interpretation that was radical at the time – but is now taken for granted – Lincoln’s historic address redefined the Civil War as a struggle not just for the Union, but also for the principle of human equality.

On the day following the dedication ceremony, newspapers all over the country reprinted Lincoln’s speech along with Everett’s. Opinion was generally divided along political lines, with Republican journalists praising the speech as a heartfelt, classic piece of oratory and Democratic ones deriding it as inadequate and inappropriate for the momentous occasion. Nevertheless, the “little speech,” as he later called it, is thought by many today to be the most eloquent articulation of the democratic vision ever written.

The Gettysburg Address Shaped American Memory of the War

Some prescient observers sensed the power of Lincoln’s achievement immediately. Everett was among them. The next day, he wrote to Lincoln, requesting a copy of the speech and covering it with praise: “Permit me also to express my great admiration of the thoughts expressed by you, with such eloquent simplicity & appropriateness, at the consecration of the cemetery. I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.” Lincoln replied gracefully, “In our respective parts yesterday, you could not have been excused to make a short address, nor I a long one. I am pleased to know that, in your judgment, the little I did say was not entirely a failure.”

Lincoln’s short speech also became a touchstone in American history, marking not only a turning point in the Civil War but also a reframing of that war as a struggle for human rights. More than tariffs, taxes, states’ rights, or any of the numerous other political differences dividing North and South, the issue of slavery has come to dominate how history remembers the conflict – thanks in large part to Lincoln’s speech. He successfully redefined the war as a fight to uphold the principles upon which the nation was founded, at the same time delivering one of the most beloved and best-remembered speeches in history.

Misunderstanding The Gettysburg Address

After Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts wrote of the address, “That speech, uttered at the field of Gettysburg, and now sanctified by the martyrdom of its author, is a monumental act. In the modesty of his nature, he said ‘the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here; but it can never forget what they did here.’ He was mistaken. The world at once noted what he said, and will never cease to remember it.”

In spite of what is widely considered one of the greatest speeches in American history, there are still a few points about the speech that are misunderstood even today.

1. Lincoln wrote every word of the Gettysburg Address.

While subsequent presidents have all enjoyed significant assistance from speechwriters in crafting their messages, President Lincoln took a more hands-on approach and is one of the few presidents in U.S. history to have written the entirety of his speeches and remarks.

2. Lincoln was not the main attraction at Gettysburg that day.

President Lincoln was invited to make a few remarks at the ceremony consecrating a new cemetery for Union soldiers, but he was not the keynote speaker. That honor went to Edward Everett, a leading academic and popular orator at the time. Everett spoke before the president, delivering a 13,607-word, 2-hour-long speech.

3. Lincoln’s speech was just 10 sentences long.

In contrast to Everett’s hours-long address, Lincoln spoke for just a few minutes. A popular myth tells of President Lincoln hastily jotting down his 273-word speech on the back of an envelope during the train ride from Washington to Gettysburg. In truth, Lincoln put a great deal of planning into his remarks. He began writing the speech the night before he left and completed it after his arrival in Pennsylvania.

4. The exact wording of Lincoln’s remarks, as delivered, cannot be historically verified.

Modern speeches are often distributed electronically to news outlets as they are delivered – if not before. In 1863, journalists had to transcribe the text as it was spoken, leading to conflicting reports as to what President Lincoln said and how he said it. Adding to the confusion, Lincoln himself penned five different versions of the text for his personal secretaries and friends.

5. The Gettysburg Address does not explicitly discuss details of the war.

One reason for the enduring power of the Gettysburg Address is its timeless appeal. Rather than linking the speech to details of the war, Lincoln instead invoked universal ideals like devotion, democracy, human equality, and the importance of honoring the sacrifice of those who died for their country. He did not once explicitly mention the Union, the Confederacy, slavery, the Emancipation Proclamation, or even Gettysburg itself. He merely acknowledged the state of civil war and the battlefield losses and commemoration, before entering into the main theme of the speech, which was the need to continue the fight for freedom, which was the cause so gravely elevated by the battle’s casualties.

6. The speech was not the first appearance of the phrase “of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

While Lincoln is often credited with creating the phrase “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” it is actually centuries older than America. The earliest usage can be found in the introduction to an English translation of the Bible by John Wycliffe in 1384 (“This Bible is for the Government of the People, by the People, and for the People.”) The phrase also turns up in the 1850s in a book of sermons by abolitionist preacher Theodore Parker, a book which Lincoln received as a gift in the first months of the Civil War, and which was likely his source of inspiration for the wording of the now-legendary phrase.

7. The Gettysburg Address argues that the Declaration of Independence is more important than the Constitution.

Thomas Jefferson himself attempted to condemn slavery in the first draft of the Declaration of Independence but was thwarted by the opposition of southern slave states. However, he was still able to include in it the declaration of the equality of all men. But when the Constitution itself was written, southern states prevented the inclusion of the issue of equality.

And so, in the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln focused on that revolutionary ideal set forth “four score and seven years ago” in the Declaration of Independence by the anti-slavery efforts of founders Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton, among others, that so eloquently stated in our founding document that “all men are created equal.” Whereas slaveholders at the time argued that they had a constitutional right to own slaves, Lincoln called on America to welcome a “new birth of freedom,” implying that the U.S. Constitution must change to embrace equal rights for all.

8. The response from those in attendance was overwhelmingly positive.

According to reports, the audience interrupted Lincoln five times to applaud his speech (though they offered only mildly polite applause at the conclusion of his remarks). Even with those five interruptions, Lincoln still managed to deliver his entire address in approximately 2-3 minutes.

9. The press response to Lincoln’s speech was divided along partisan lines.

While the speech is hailed today as one of the greatest in history, contemporary responses were split with pro- and anti-Lincoln publications divided along party lines. The Democratic-leaning Chicago Tribune, for instance, called the speech “dish watery.”

10. There is only one known photograph of President Lincoln at the ceremony.

Lincoln was captured in a photo of the crowd at the ceremony, with his head visible in the mass of people. Historians speculate that the brevity of Lincoln’s remarks prevented photographers from setting up their complicated equipment in time to catch the president while still on stage. The photograph was taken by 18-year-old David Bachrach, who would later become notable as the uncle of writer Gertrude Stein.

The Gettysburg Address

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that this nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

*********************************

The rest, as they say, is history. With time, and frequent reprinting’s, it became obvious that Lincoln had created a lapidary masterpiece, whose brevity was not the least of its merits. He succeeded in giving meaning to the terrible sacrifice, and in repurposing the United States. He elevated democracy and equality as fundamental goals of the government. And he changed the way we talk. His 273 words were short – mostly one- and two-syllable words, derived from Anglo-Saxon and Norman roots, the way that Americans actually spoke. Notably absent were flowery Greek and Latin phrases.

Read About Other Military Myths and Legends

If you enjoyed learning about Gettysburg Address, we invite you to read about other military myths and legends on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

I am humbled every time I reread this Address. I agree it is the best use of the English Language as spoken by Americans, that has ever been written.

Hello. And Bye.

When in grade school we memorized and delivered the speech in class. It was a very moving and meaningful experience. A visit to Gettysburg as an adult brought the event full circle.