Japan’s ambition as a world power began in the late 1800s, but lacking in raw materials (oil, iron, and rubber) necessary to make it a reality, it seized material-rich colonies and islands. Ensuring they kept what they seized, Japan established naval and army bases throughout the Pacific. Following long-standing complaints from the United States about their laying claims on territories that did not belong to them, Japan’s military leaders unwisely decided to attack America, beginning with the infamous surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the naval officer, tasked with planning and carrying out the attack, said: “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.” His insightful prophecy became a horrible reality for Japan.

The Battle of Iwo Jima Was Part of a Bigger Strategy

As the Americans prepared to take the offensive in 1942, military planners realized it would be impossible to recapture every Japanese-held island in the Pacific, so a strategy of “island-hopping” was created. This allowed Allied forces to bypass heavily fortified, sizable Japanese garrisons and instead concentrate its limited resources on strategically important islands that were not well defended but capable of supporting the drive to the main island of Japan.

By early 1945, American forces had re-taken a sweeping number of islands held by the Japanese. For all its gains, however, two small Japanese homeland islands – Iwo Jima and Okinawa – remained critical to a successful invasion of Japan. Capturing these two heavily defended islands would give American forces vital staging areas and airfields within the bombing range of Japan.

Japanese Defenses Made the Battle of Iwo Jima Unpredictable

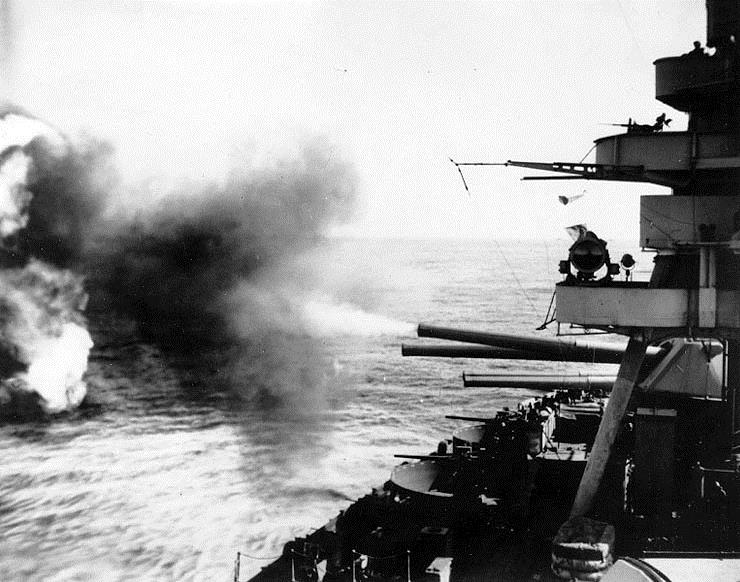

Iwo Jima was attacked first. After ten weeks of relentless bombing from carrier-based planes and medium bombers – the heaviest up to that point in the war – it was thought the island defenses would be in ruins. That was not to be. The island commander, Lt. General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, prepared his defenses it depth, having constructed a vast array of interlocking fortified positions connected by a large network of underground tunnel and caves providing cover from naval fire and aerial bombs.

At 2 a.m. on February 19, 1945, as the Marine landing force lay off shore, U.S. ships and aircraft delivered pre-landing fires. Still, like the earlier ship and aerial bombardments, it proved largely ineffective due to the nature of the Japanese defenses.

The next morning, at 8:59 a.m., the first landings began as the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Marine Divisions came ashore. Early resistance was minimal. This proved to be only a trick to draw the exposed Marines onto the beaches. It was then that determined Japanese defenders, led by Kuribayashi, opened up from their concealed mountain defenses.

The Battle of Iwo Jima Was Won Inch by Inch

Against these defenses, the Marine now had to advance. Subject to relentless gunfire and shelling from Japanese artillery, they moved by the inch, not the mile. It took four days to advance 1,000 yards, scale Mt. Suribachi, and plant the flag captured in Joe Rosenthal’s iconic photograph. But Marines still had to root out Japanese defenses stretched across the four-mile-long island. Even as American planes dropped bombs and napalm on Japanese concrete bunkers, they clung tenaciously to their positions forcing the Americans to roust them out bunker by bunker. Following a final Japanese assault during March 25-26, Iwo Jima was secured after 36 days of brutal combat.

The Cost of Victory in the Battle of Iwo Jima

But victory came at a heavy price. At the battle’s conclusion, 6,281 Americans and more than 20,000 Japanese were killed. Twenty-two Marines and five sailors received the Medal of Honor for their actions on Iwo Jima – the most bestowed for any campaign. Admiral Nimitz remarked, “Among the Americans who served on Iwo Island, uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

After the Battle of Iwo Jima: The Road to Okinawa

Next came Okinawa, where the Japanese had more than three times the force than what had been committed to Iwo Jima.

The Americans paid an even greater price for Okinawa: 12,000 Allied dead and another 38,000 wounded. But the Japanese lost more than 100,000 men and an island critical to the defense of Japan. The end of the battle left little doubt that the end of the war was near.

Although the battles for Iwo Jima and Okinawa were the most deadly and significant in the approach toward Japan, it was the battle of Iwo Jima that earned a place in American lore with the publication of Rosenthal’s iconic photograph showing the U.S. flag being raised on the fourth day of the battle. The photograph was extremely popular, being reprinted in thousands of publications. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Photography that same year and ultimately came to be regarded as one of the most significant and recognizable images of war.

But that flag-raising was not the first. A 40-man combat patrol climbed Mt. Suribachi to attack and capture the mountaintop and raise the American flag to signal that the volcanic mountain was captured. The photograph of that flag raising by five Marines was shot by Photographer Staff Sgt. Louis R. Lowery. But the flag was too small to be seen easily from the nearby landing beaches on Iwo Jima, so a second, larger replacement flag with a longer and heavier pipe was planted hours later by five Marines and a Navy medical corpsman, resulting in the famous photograph taken by Joe Rosenthal.

One Photograph Made History

According to Ruth Ben-Ghiat, a professor of history and a specialist in 20th-century European history, Rosenthal’s photo became the more popular of the two because of how he captured the moment but also transcended it with its diagonal back-leaning position contrasting with the forward motion of the soldiers: “They seem to rise out of the ash and other detritus of the battlefield, and there is already something sculptural in their massed bodies, in their muscular legs and arms that strain to hoist up the heavy pole. The leg of the lead bearer crosses the flagpole, adding a further sense of solidity,” she wrote about the photograph. She also wrote that there is something deeply reassuring about this photograph in its display of strength and teamwork and its communication of a push forward to victory. “The fact we cannot see their faces also works to lift the image out of its original context, lending it a universal quality,” she added.

On July 2, 1945, while marines, soldiers, and sailors rested, trained, and prepared for the expected invasion of mainland Japan, the first atomic bomb was tested in New Mexico. An alternative to the invasion was now a definite possibility. On the morning of August 6, 1945, an atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima. Three days later, Nagasaki suffered a similar fate.

No mainland invasion would take place; the fighting and the war was over.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the The Battle of Iwo Jima, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

In 1965 I was serving as the Commanding Officer of the US Coast Guard LORAN Station on Iwo Jima. I received a MSG from the U.S. Marine Command on Guam asking if I could assist them in conducting a 20th Anniversary Ceremony on Iwo Jima. They indicated that the USAF had advised them that there was insufficient time to obtain clearance for a Ceremony. I quickly responded “Yes” and approved their request for a 4 air craft landing from Guam for those persons they intended for the Ceremony; Marine Band, returning Marine Corps Veterans of Battle of Iwo Jima, etc; as “visiting” the Coast Guard Station. They then advised that Joe Rosenthal had requested to attend, but apparently the Marine Corps did not desire his attendance, so could I restrict attendance for their Ceremony to “No Civilians”, which I did. Then, they advised that one of the reported “original flag raisers” , Rene Gagnon, wanted to attend. His wife owned a Travel Agency and had.as a promotion, offered a prize of a “Trip to any place in the World to the winner”. The winner was “Rene Gagnon”, and he desired to visit Iwo Jima, on the day of the 20th Anniversary of the Flag Raising. Thus they would require an exception to the “No Civilians”, as he wanted to bring his wife, to which I agreed. The Ceremony went off as scheduled, and I welcomed the arrival, provided transportation, hosted a Steak Lunch at our Coast Guard Station for all attending, and joined in this Memorial Event, which was a highlight for my crew as well. I met with Rene Gagnon, and his wife and son, and went with him to Invasion Beach following the Ceremony. There he kneeled in the sand and removed a vial from his pocket containing “Black Sand” which he said contained sand he removed during the original battle. He scattered this sand onto the beach, then prior to leaving refilled the vial with new sand from the beach. Just after the Passing of Rene Gagnon it was revealed that further evidence had.found that he was not one of the Flag Raisers pictured in Joe Rosenthal’s famous photo, along with John Bradley.