The War of 1812 is a relatively little-known war in American history, but it is also one of its most important. It lasted from June 1812 to February 1815, and was fought between the United States of America and the United Kingdom, its North American colonies, and its Native American allies. It also defined the presidency of James Madison, known as the “Father of the Constitution.” Despite its complicated causes and inconclusive outcome, the conflict helped establish the credibility of the young United States internationally. It also fostered a strong sense of pride among the American people that is reflected and preserved in one of the fledgling nation’s most famous patriotic songs, the U.S. national anthem.

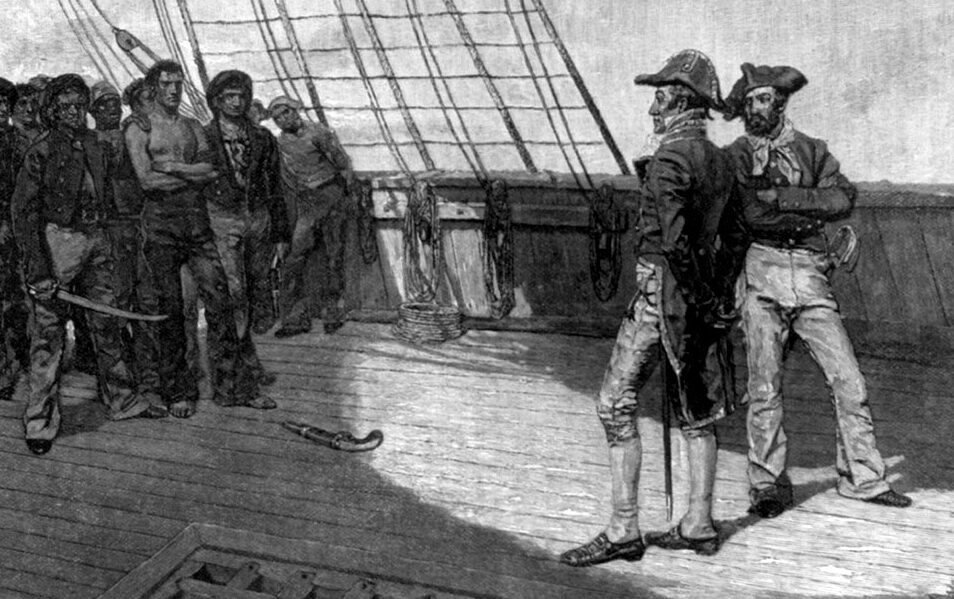

Causes of the war included British attempts to restrict U.S. trade, the Royal Navy’s forced impressment of as many as 10,000 American merchant sailors, and America’s desire to expand its territory. The United States suffered many costly defeats at the hands of British, Canadian and Native American troops over the course of the War of 1812, including the capture and burning of the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C., in August 1814.

Nonetheless, American troops were able to repulse British invasions in New York, Baltimore, and New Orleans, boosting national confidence and fostering a new spirit of patriotism. The ratification of the Treaty of Ghent on February 17, 1815, ended the war but left many of the most contentious questions unresolved. Nonetheless, many in the United States celebrated the War of 1812 as a “second war of independence,” beginning a new era of partisan agreement and national pride.

At the outset of the 19th century, Great Britain was locked in a long and bitter conflict with Napoleon Bonaparte’s France. In an attempt to cut off supplies from reaching the enemy, both sides attempted to block the United States from trading with the other. In 1807, Britain passed a series of decrees called the Orders in Council, which required neutral countries to obtain a license from British authorities before trading with France or its colonies, outraging many neutral trading partners. In 1809, the U.S. Congress repealed Thomas Jefferson’s unpopular Embargo Act, which, by restricting trade, had hurt Americans more than either Britain or France. Its replacement, the Non-Intercourse Act, specifically prohibited trade with Britain and France. It also proved ineffective, and in turn was replaced with a May 1810 bill stating that if either power dropped trade restrictions against the United States, Congress would in turn resume non-intercourse (blocking trade) with the opposing power. As a result, that November, after Napoleon hinted he would drop restrictions, President James Madison blocked all trade with Britain, contributing to already-tense relations between the two countries. This maintained a natural alliance between the U.S. and France against Great Britain that began during the Revolutionary War just a few decades prior.

Meanwhile, new members of Congress elected that year – led by two popular statesmen, the famous orator and future Speaker of the House and Secretary of State Henry Clay, and political theorist and future Vice President John C. Calhoun – had begun to agitate for war, based on their indignation over British violations of maritime rights as well as Britain’s encouragement of Native American hostility against American expansion in the West, allying the British with a confederation of native American forces led by Shawnee chief Tecumseh.

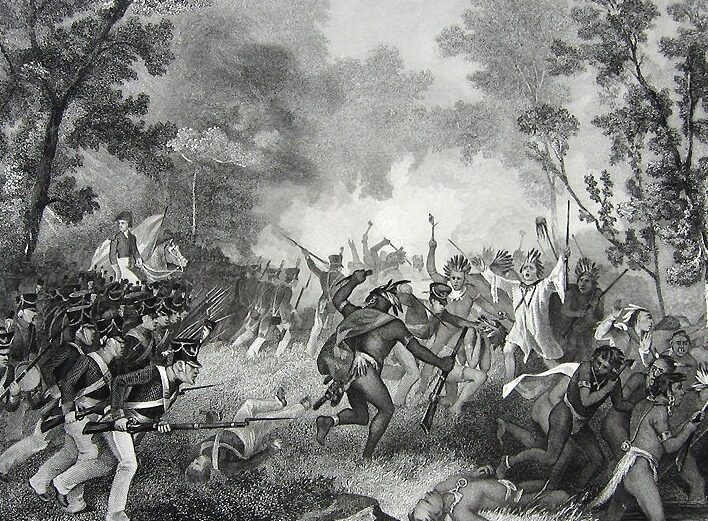

Lacking artillery and strength of numbers, these Indian allies of the British avoided pitched battles and head-to-head conflicts that could potentially result in heavy losses. They sought only to fight under favorable conditions, relying on mostly irregular warfare, including raids and ambushes. Their weapons were mostly primitive, including a mixture of tomahawks, clubs, knives, and arrows. But British-supplied swords, rifles and muskets gave them the ability to effectively conduct asymmetric warfare. Indian warriors were brave, but being outnumbered led to tactics that favored a more defensive approach to fighting, risking little and only striking when they had the advantage.

The Beginning of the War of 1812

In the fall of 1811, Indiana’s territorial governor William Henry Harrison led U.S. troops to victory over the native confederacy in the Battle of Tippecanoe, earning him a reputation that eventually carried him to the White House. The defeat convinced many Indians in the Northwest Territory that they needed, even more, British support to prevent American settlers from pushing them further out of their lands. Americans on the western frontier demanded an end to this British intervention and support of the native confederacy, adding to the tensions.

By late 1811 the so-called “War Hawks” in Congress were putting more and more pressure on Madison, and on June 18, 1812, the president finally signed a declaration of war against Britain. Though Congress ultimately voted for war, both the House and the Senate were bitterly divided on the issue. Most Western and Southern congressmen supported the war, while Federalists (especially New Englanders who relied heavily on trade with Britain) accused war advocates of using the maritime rights issue to promote their expansionist agenda.

In order to strike at Great Britain, U.S. forces almost immediately attacked Canada, then a British colony. The British government believed it to have been an opportunistic ploy by President James Madison to annex Canada while Britain was fighting a ruinous war with France. The view was shared in much of New England and for that reason, the war was widely referred to there as Mr. Madison’s War. As a result, the primary British war goal was to defend their North American colonies. However, some historians believe that the U.S. only intended to capture Canada in order to cut off food supplies for Britain’s West Indian colonies and prevent the British from continuing to arm the Indians, as well as creating a bargaining chip to force Britain to back down on the maritime issues.

American officials were overly optimistic about the invasion’s success, especially given how underprepared U.S. troops were at the time. On the other side, they faced a well-managed defense coordinated by Sir Isaac Brock, the British soldier and administrator in charge in Upper Canada (modern Ontario). On August 16, 1812, the United States suffered a humiliating defeat after Brock and Tecumseh’s forces chased the forces of Michigan’s William Hull across the Canadian border, scaring Hull into surrendering Fort Detroit without firing a shot.

Things looked better for the United States in the Northwest Territory, as Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry‘s brilliant success against the Royal Navy in the Battle of Lake Erie in September 1813 placed the territory firmly under American control. Harrison was subsequently able to retake Detroit in October 1813, with a victory in the Battle of Thames, in which Tecumseh was killed. Tecumseh’s passing weakened the native resistance to American expansionism and forced them to retreat westward. But Tecumseh subsequently became an iconic folk hero in American, Aboriginal, and Canadian history, being the subject of books, movies, documentaries, and a yearly outdoor theater drama in Chillicothe, OH that recreates his powerful speech to the leaders and warriors of his tribal confederacy from atop a large rock, prior to the raid that helped the British capture Fort Detroit.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy had been able to score several victories over the British Royal Navy in the early months of the war. With the defeat of Napoleon’s armies in April 1814, however, Britain was able to turn its full attention to the war effort in North America and began mobilizing its forces against the United States. As large numbers of troops arrived, British forces raided the Chesapeake Bay and moved in on the U.S. capital, capturing Washington, D.C. on August 24, 1814, and burning government buildings, including the Capitol and the White House.

On September 13, 1814, Baltimore’s Fort McHenry withstood 25 hours of bombardment by the British Navy. The following morning, the fort’s soldiers hoisted an enormous American flag, a sight that inspired Francis Scott Key, imprisoned on a Royal Navy ship and witness to the battle, to write a poem he titled “Defence of Fort McHenry.” Later set to the tune of an old English drinking song, the poem became the lyrics for “The Star-Spangled Banner” which was adopted as the U.S. national anthem. The Battle of Baltimore resulted in American forces repulsing sea and land invasions of the busy port city of Baltimore, Maryland, and the death of the commander of the invading British forces. British forces subsequently left the Chesapeake Bay area and began gathering their efforts for a campaign against New Orleans.

Peace Treaty and the End of the War of 1812

By that time, peace talks had already begun at Ghent (modern Belgium), and Britain moved for an armistice after the failure of the assault on Baltimore. In the negotiations that followed, the United States gave up its demands to end impressment, while Britain promised to leave Canada’s borders unchanged and abandon efforts to create an Indian state in the Northwest. On December 24, 1814, commissioners signed the Treaty of Ghent, which would be ratified the following February. On January 8, 1815, unaware that peace had been concluded, British forces mounted a major attack on New Orleans, only to meet with defeat at the hands of future U.S. president Andrew Jackson’s army. News of the battle boosted sagging U.S. morale and left Americans with the taste of victory, despite the fact that the country had achieved none of its pre-war objectives.

Though the War of 1812 is remembered as a relatively minor conflict in the United States and Britain, it looms large for Canadians, who see it as vindication for maintaining their national boundaries, and for Native Americans, who see it as a decisive turning point in their losing struggle to govern themselves. In fact, the war had a far-reaching impact in the United States, as the Treaty of Ghent ended decades of bitter partisan infighting in the U.S. government and ushered in the so-called “Era of Good Feelings.” The war also marked the demise of the Federalist Party, which had been accused of being unpatriotic for its antiwar stance, and reinforced a tradition of Anglophobia that had begun during the Revolutionary War. It birthed a new generation of great American generals and helped propel 4 men to the presidency: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, James Monroe and William Henry Harrison. Perhaps most importantly, the war’s outcome boosted national self-confidence and encouraged the growing spirit of American expansionism that would shape the better part of the 19th century.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the War of 1812, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

Interesting read

A significant omission in this otherwise good narrative is that Stephen Girard of Philadelphia, a French-born mariner, merchant and banker, who was at the time the wealthiest man in the US, pledged his entire fortune in support of the American effort. The US Treasury was essentially broke at the time, and Girard’s singular contribution made it possible for the country to endure and prevail. Girard has never been recognized with so much as a postage stamp, but without his patriotism, we would be flying the Union Jack today.