In December 1941, as Japan ripped across the Pacific, most American outposts collapsed in days. Guam fell between Dec. 8 and Dec. 10 to a larger Japanese landing force after only brief resistance by a small, lightly armed garrison of sailors and Marines. Wake Island was supposed to be another speed bump. Instead, a few hundred Marines, sailors, and civilian contractors turned it into a two-week fight that delivered the first American tactical victory of the Pacific War and a badly needed morale boost at home.

The Defense of Wake Island Faces Long Odds From the Start

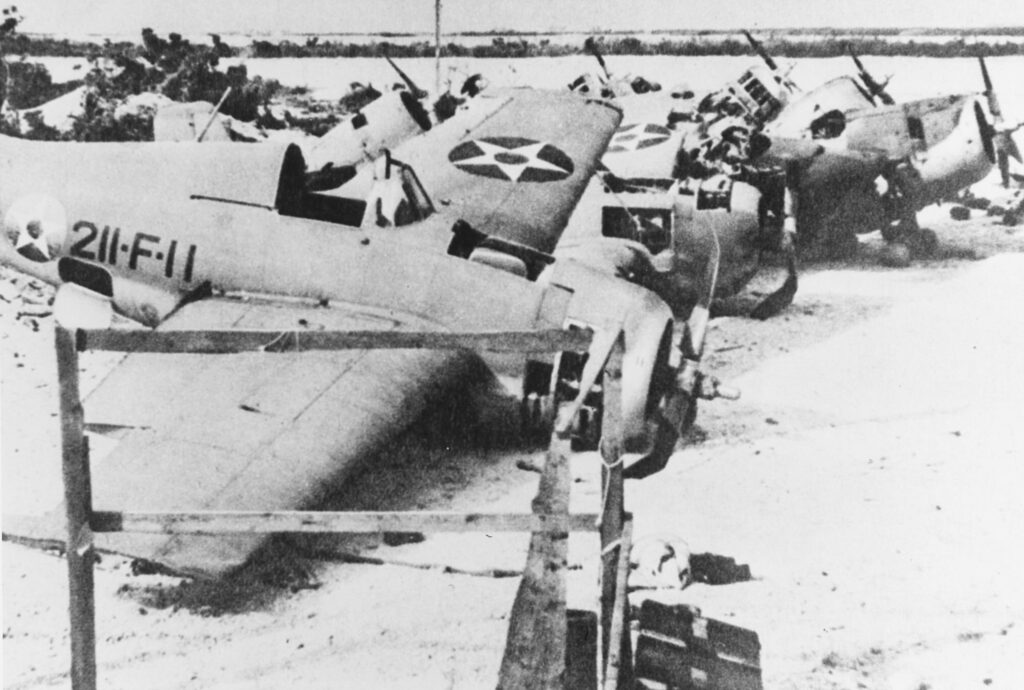

Wake was an odd prize: a wishbone-shaped coral atoll about 2,000 miles west of Oahu, made up of three low islets named Wake, Wilkes, and Peale. By early December 1941, the U.S. had turned it into an unfinished outpost with roads, a triangular airstrip, and basic naval air facilities built by more than 1,100 civilian contractors. The garrison itself was tiny but well armed. On Dec. 4, 1941, the island held 449 Marines, 69 sailors, and a six-man Army radio detachment— only 524 officers and men in all. Most belonged to the Wake Island detachment of the 1st Defense Battalion, backed by Marine Fighting Squadron 211 with 12 F4F-3 Wildcat fighters.

The Marines were so few in number that they could not fully man the island’s defenses, but what Wake lacked in manpower, it made up for in hardware. The Marines had 12 3-inch antiaircraft guns, 6 5-inch seacoast guns, six searchlights, 18 .50-caliber antiaircraft machine guns, and 30 .30-caliber guns, dug into coral gun pits they’d carved mostly with picks and shovels. That gave them a real ability to hurt ships and aircraft, which is something Guam never had. Official U.S. accounts of the Guam fight explicitly describe its 1941 defenders as a “small, lightly armed garrison” that was “quickly overrun” between Dec. 8 and 10.

The Defense of Wake Island Faces Early Japanese Air Attacks

Wake’s war started hours after Pearl Harbor. On the morning of Dec. 8 (Wake being west of the International Date Line), the island’s Army radio trailer received an emergency message from Hawaii: Oahu was under attack. Just before noon, 27 Japanese medium bombers from the Marshalls burst out of the clouds over Wake at about 2,000 feet. The garrison hesitated briefly, thinking they might be American B-17s, and paid dearly for it. The bombers destroyed seven of VMF-211’s Wildcats on the ground and killed or wounded about half the squadron’s personnel in minutes.

Rather than sit still and wait for the next raid, the Marines adjusted. Anti-aircraft crews moved their 3-inch guns to new positions, improved camouflage, and used wooden dummies at the old sites. Later raids would waste bombs on the decoys while the real guns fired from fresh locations. Civilian contractors volunteered by the hundreds to reinforce defenses, joining gun crews, belting ammunition, repairing aircraft, and hauling sandbags and hot food to the outer positions.

A Small American Garrison Shocks Japan With a Naval Victory

The first decisive test came on Dec. 11. Confident that earlier bombing had neutralized Wake, Rear Adm. Sadamichi Kajioka approached at dawn with a “Wake Invasion Force” built around three light cruisers, six destroyers, two patrol boats, two transports, and submarines carrying about 450 Special Naval Landing Force troops.

Wake’s defenders didn’t panic and open fire the moment the ships appeared, but they did fume as the Japanese ships approached. Orders from Maj. James Devereux, commanding the 1st Defense Battalion detachment, told them to hold their fire until the cruisers drew close. Devereux knew the ship out ranged his six 5-inchers. His only hope was to hold fire and draw the Japanese into point-blank range. As Kajioka’s flagship, the light cruiser Yubari, ran into about 8,000 yards and began its firing run, the rest of the flotilla followed, pounding the island and setting fuel tanks ablaze. The Marines, under strict orders, kept their guns silent.

Only when Yubari turned into a third firing run at roughly 4,500 yards did Devereux finally give the order to open fire. The 5-inch battery on Wilkes Island, “playing possum” until then, found the range on the destroyer Hayate, scored direct hits, and blew the ship apart in view of the defenders. Other batteries hit additional ships, and Kajioka turned away, believing he was escaping the trap. Instead, he ran headlong into the air side of Wake’s defense.

VMF-211 had only four serviceable Wildcats left, but they flew ten attack sorties against the retreating force, strafing decks and dropping 100-pound bombs. A lucky hit on the stern of the destroyer Kisaragi detonated her depth charges and sent her to the bottom as well. Later that day, a Wildcat on patrol sank a Japanese submarine that surfaced too close to the atoll.

At the cost of two fighters damaged and five Marines lightly wounded, Wake’s garrison had repulsed the landing, sunk two destroyers, and damaged other ships. Historians of the battle and Marine Corps official narratives consistently describe the Dec. 11 fight as America’s first tactical victory of the Pacific War and the first unsuccessful amphibious assault mounted by either side in that theater.

The contrast with Guam could not have been sharper. Where Guam’s lightly armed garrison was brushed aside in three days, Wake’s coastal artillery and handful of fighters inflicted disproportionate losses and forced a Japanese admiral to retreat.

The victory reverberated far beyond the atoll. Reports of the “little island that fought back” reached the United States just as Americans were processing Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, and the loss of Guam and Hong Kong. President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself held up Wake as evidence that U.S. forces could and would hit back, and the battle quickly became a potent rallying point for a shaken public.

The Defense of Wake Island Ends in Defeat but Not in Failure

Japan was determined not to be embarrassed a second time. In the days after Dec. 11, the Imperial Navy reinforced Kajioka with four heavy cruisers, additional destroyers, a seaplane tender, and two carriers from the Pearl Harbor strike force, Soryu and Hiryu, along with roughly 1,600 more Special Naval Landing Force troops. Carrier aircraft smashed Wake on Dec. 21 and 22, shooting down the last two Wildcats and further degrading the gun defenses.

On Dec. 23, the Japanese returned, this time avoiding a daylight gunnery duel. Around pre-dawn, they beached two high-speed transports and ran in additional landing craft under cover of darkness, putting roughly 900 SNLF troops ashore in the first wave.

At that point, the battle shifted from artillery and air power to close-quarters infantry combat. The Marine Corps had always taught that every Marine is a rifleman first. On Dec. 23, that doctrine became brutally literal. With many of the big guns damaged or without fire-control equipment, Devereux’s Marines left their pits and fought as infantry, joined by grounded VMF-211 pilots, sailors, and several dozen armed contractors.

For more than 11 hours, small groups of Americans counterattacked, moved reserves by truck, and tried to seal off beachheads before the Japanese could consolidate. At one landing point, they virtually wiped out a beachhead of nearly 100 SNLF troops; near the airfield, they drove enemy forces back roughly 900 yards in a local counterattack. The fight on Wake’s south shore was not a quick collapse, but a grinding, island-wide firefight.

Wake finally fell for reasons that had little to do with the defenders’ tactics. Carrier aviation had destroyed its remaining fighters and severely damaged its guns. A relief expedition sent from Pearl Harbor was recalled before it could arrive. Severed communications and fragmentary reports led CDR Winfield Cunningham to believe most of his strong points had been overrun. Facing that picture, and with no hope of reinforcement, he ordered surrender to prevent what he thought would be a massacre.

By then, the price Japan paid was steep. Estimates say the Imperial Japanese Navy lost two destroyers, one submarine, 21 aircraft, and around 900 to 1,000 men to take an atoll defended by fewer than 600 American military personnel. Fewer than 100 Americans died during the 16-day siege.

Strategically, Wake Island’s loss did not halt Japan’s early-war momentum. But the way its defenders fought mattered. They used coastal guns with disciplined fire control, coordinated their tiny air wing with artillery to ambush a superior fleet, and, when the guns were silenced, fought as agile infantry, counterattacking instead of waiting passively to be overrun. In a month mostly filled with disasters, Wake showed that determined defenders with decent tools and smart tactics could still bloody the Japanese Empire’s nose.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning about the The Defense of Wake Island, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

This is a brief news column I wrote quite a while ago, but I thought it might provide a Post Script to the Alamo of

of the Pacific story.

Hero in the Dress Shop

It wasn’t a task I was looking forward to doing. The “guy-who-owns-the-dress-shop” (as my salesperson put it) was angry at the newspaper I managed, so it was my job to go see if I could sooth the feelings of a regular advertiser. I tried not to judge in advance, but one thought wouldn’t go away: What sort of MAN owns a dress shop? Was I going to be facing an angry, effeminate character or just an irate, prissy sort of guy who might want to cry on my shoulder?

Actually, the gentleman in question was angry at our local “gossip” columnist. She had purchased a dress, wore it to a party and then wanted to return it for cash. He was wise to that trick, so he had a strict “Exchange Only” return policy. The columnist, a large, rather over-bearing woman who obviously enjoyed her position of power, had threatened to criticize him in the newspaper, and, according to the advertising rep, Gene at the dress shop “was going ballistic.”

So, in I walked to meet and sooth Gene, but instead of the whining character I expected, I ended up talking at length with one of the bravest men I ever expect to meet.

Gene was an older man with a round belly and a nearly bald head, and his wife had originally owned and managed the dress shop, but when she died, Gene kept it going, probably just to stay busy. We sat down in the back room, surrounded by women’s clothing on shelves and racks, so he could explain to me why he wouldn’t stand for the threats of the columnist, because “he’d been threatened by the best.” That’s when I discovered who the dress shop owner really was, because “The Best” to Gene meant the prison guards of the Japanese Imperial Army of World War II.

Back at the beginning of World War II, just after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Navy decided they could quickly capture lonely Wake Island, a small piece of land far out in the Pacific Ocean with nothing but an air strip to make it militarily important. It was held by a detachment of U.S. Marines, a few Navy sailors and a group of civilian contractors from Guam who ran the air station. The Japanese thought they could capture the island in a day, but the American military men and the civilians dug in, repulsed the first invasion attempt with significant losses to the Japanese attackers, then held out for almost 2 weeks, earning it the nickname “The Alamo of the Pacific.” When the Japanese forces finally overwhelmed little Wake Island, the surviving Marines and sailors were shipped off to prison camps where they were starved, brutalized, and many were worked literally to death. The Guamanians had to remained on Wake, where they forced to repair the damaged airfield before they suffered a mass execution.

Gene, the future dress store owner in California, managed to survive being one of the longest-held American prisoners of the Japanese Army, although he changed from being a strong, tough Marine into an 80-pound skeleton by the end of the war. It took months and months to rebuild his body after he arrived back stateside, but Gene gradually recovered as young men do. Eventually he met a nice girl and built a good life, and now he was living quietly in our ski resort town, taking care of his deceased wife’s business. Gene was not about to be threatened by a customer — no way, no how. And I agreed. Gene would face no further threats from a bullying news columnist.

I had to ask Gene if he still hated the Japanese, and he surprised me by saying he didn’t. In fact, he said he knew several Japanese Californians, and he thought they were wonderful people. He mentioned that the common Japanese soldiers suffered brutality from their officers, so why shouldn’t they treat their prisoners roughly since they didn’t respect them? To surrender was a disgrace in the Japanese military. He also noted that the rations for the prisoners weren’t terribly different than the guards, but the American and British prisoners were so much larger than the Japanese guards that they were slowly starved into walking skeletons.

Gene said that his opinion of wars had changed after the brutality he had suffered. “Wars are just terrible things,” Gene said. “Nothing good can be said of them.”

It was difficult to picture this elderly man as a survivor of such lengthy suffering. Later I would meet more. Now it was as difficult to imagine Gene as a strong and fit young man as it was to picture him emaciated and sickly. He was neither young nor fit, but he had a certain look about the eyes, a deep sorrow from a life with more pain and loneliness than normal. Given what Gene had gone through, a life spent with dresses and fashions made sense. He had certainly spent a lot of time away from such things, and they hadn’t been happy times.

I’m sure that Gene has probably passed away by now, like most WWII veterans. But if there is a place of refuge in the next life, I hope there will be many old buddies to greet Gene on his arrival. And I hope there will be plenty to eat and lots of soft things around. The guy from the dress shop, like so many millions who have suffered in hard places, deserves that.

This is such a great and incredible story. I loved it mostly because of the part about Wake island. I remember watching a movie, when I was a kid, about the battle of Wake island. I remember feeling so great about the defenders driving back the Japanese that it send a chill up my back. It was probably the first of many stories that kept building the patriotism in my soul. Then later in life I learned about the battle of Fort McHenry, during the War of 1812, when its defenders, Americans, refused to surrender to a massive British force and drove them back. These stories and many more was my driver to join the military and go to Vietnam and served 3 tours. When I left. I couldn’t help but to feel like I still haven’t done enough, but I’m sure like so many others, we did our very best. So thanks for sharing. God Bless America!