PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

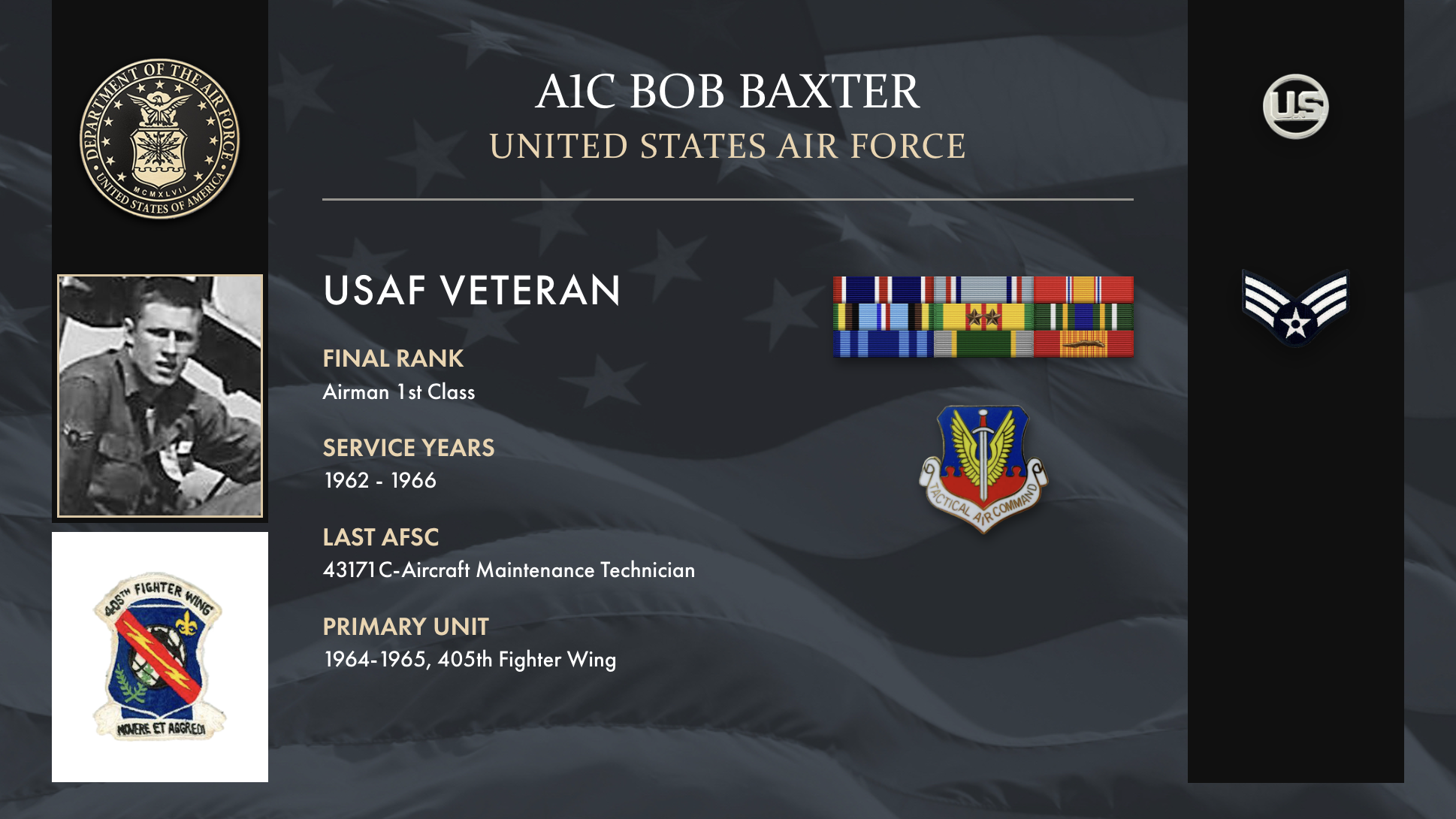

The following Reflections represents A1C Bob Baxter’s legacy of his military service from 1962 to 1966. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Air Force.

My South East Asia Experience: Working on the Canberra B-57, November 10, 1963, to May 9, 1965: I joined the Air Force at the age of 19 in 1962 for no reason other than that I was unemployed, immature, and had no goals or direction for my future. My recruiter told me that aircraft mechanics were needed, and I fit their profile. So, off I went to Basic Training, followed by Technical Training at Amarillo AFB. I graduated as an aircraft mechanic helper. My OJT continued at Scott AFB, Illinois, until November 1963. This was the start of the aviation career that I have pursued for over 50 years. As I reflect on those years from 1962 to 1966, I can see why so many of us young men grew up quickly. We had some good times and some exceptionally bad times, but we bonded together. Many of us were lucky and came home. I was able to take full advantage of the extensive training and experience provided to me during my four years in the Air Force. I was convinced early that I would stay in the Air Force for thirty years. On November 1, 1964, the reality of war hit home.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. Where did you go to basic training, and what units, bases, or squadrons were you assigned to? What was your reason for leaving?

On November 10, 1963, I arrived at Yokota AFB, Japan, on my first overseas assignment. I immediately found the Beer Garden, and to my delight, a 12-ounce can of beer was ten cents, and a carton of cigarettes was $1.10. How lucky can a 20-year-old be with a two-year assignment in Japan? What a life, living in Paradise on a paycheck of $61.00 a month, all I can eat, and a place to live. I enjoyed every day at Yokota. The base was very large, and there were many activities. There were no restrictions on travel off base. The exchange rate was 360 Japanese Yen to $1.00. We could buy all the electronics, such as cameras, stereos, and tape recorders, at a good savings. Most of us took advantage of the cost of the Japanese Motorcycles. A new Honda CB250 cc was the hot bike at the time and only cost $375.00.

I was assigned to the 3rd Operational Maintenance Squadron, 3rd Bomb Wing, and 8th Bomb Squadron as an assistant Crew Chief on the Canberra B-57. The 3rd Bomb Wing was comprised of the 8th, the 13th, and the 90th Bomb Squadrons working on a total of 47 B-57’s The 8th Bomb Squadron’s markings consisted of a Yellow Nose and yellow diagonal stripe around the waist of the fuselage with a large Yellow Tail Letter on the vertical stabilizer that identified the aircraft The 13th Bomb Squadron used red (R), and the 90th used blue (B) as their markings We had five B-57C dual control model aircraft that were used for training with the color green (G) as their markings My primary aircraft was Yellow Papa (YP), 53-3882 and the primary crew was Captain Charles Lovelace and Navigator Captain Charles Lowe Once I became familiar with the B-57 I was promoted to Crew Chief and placed on the rotation list for Korea.

Our mission at Yokota was to support a Nuclear Alert Pad in Kunsan, Korea. Kunsan, K-8, or Pad C, as it was sometimes called, maintained a squadron-strength detachment of B-57s that were always on 15-minute quick-strike alert against targets on the mainland of China, North Korea, and the USSR. B-57s rotated weekly back and forth from Pad C, giving the flight crews two-week tours at the Pad. The ground crews rotated every 90 days.

Saturday Morning, November 23, 1963

Just 13 days after arriving in Japan, the alert horns all over the base started sounded The base was closed down and we were all told to report to the flight line for possible deployment The Crew Chiefs were said to get their aircraft ready for deploy ASAP Then for the next 8 hours we sat and waited It was war for sure, but no one knew with whom That night we finally got back to the barracks and had the evening to reflect on our futures A few days later, several of the B-57’s and crews returned from Pad C as part of their normal two week rotation As soon as the canopy opened, I was on the ladder asking the crew what happened on the Pad the morning President Kennedy was assassinated I was told Pad C went on alert at 4:00 am The crews rushed out in the cold winter morning and strapped in but were told not to start their engines They were to sit and wait for verbal notification from the Operations Officer to start their engines They sat strapped in the cold, soaked aircraft for 6 hours on hold with radio silence The ground crews huddled next to the APU trying to keep warm until the word came to stand down Twenty-four aircraft were sitting ready, each with a Nuclear Bomb and a designated target The end of civilization as we knew it seemed so very close We gave thanks to the Presidential Advisors in the situation room when President Johnson ordered a stand down.

Kunsan, Korea, Pad C or K-8

On January 1, 1964, I boarded a C-123 along with 53 other Crew Chiefs, Assistants, and Armament Specialists headed for our 90-day tour on the Pad. I was looking forward to the experience but had no idea what to expect. When we arrived, I met with M/Sgt. Banka, the Line Chief, M/Sgt. Ramsay “B” Flight Leader and my immediate supervisor, Sgt. Ramsay assigned me to an aircraft as Crew Chief, and an assistant H. pointed to the Quonset hut that would be my home for the next 90 days. The living area gave each man enough room for a locker and a GI bunk. Two Quonsets were bolted together, making them long enough to put the Crew Chiefs together. The same arrangement was made for the Assistant Crew Chiefs. There was also an area for the Armament Troops we called the “A” Men. The living space was tight, with only a bunk, an old wall locker for each man, and an oil-burning stove for heat.

Life on the Pad

Our entertainment was a ping-pong table in the hangar or playing pinochle and hearts each day. A B&W movie was scheduled in a Quonset hut converted into a theater at night. All the movies shown were black-and-white. They were very similar to the “movie night” episodes of the TV series M.A.S.H. when Radar would run the 16mm projector.

All of the enlisted men lived inside the double fenced compound very close to the aircraft Every day, once in the morning and once in the evening, the aircraft team consisting of the Pilot, Navigator, Crew Chief and Assistant walked out to his assigned aircraft for a visual inspection As we approached the aircraft, an armed guard would check out our Pad ID’s and only then could we walk toward the aircraft Each plane was parked inside a large circle which we were not allowed to cross I was always concerned about fuel and hydraulic leaks My walk around concentrated on these areas My assistant concentrated on wing surface and flight control ice We had wing and engine covers that were used to keep the snow and ice off the surfaces, but after a deep snow and freeze we had to remove the covers and dry them out in the hangar The aircraft team was on a duty schedule of six days on and one day off for the month A crew took the same day off “Roving” crews were used to fill in for the crews that had days off.

Pad Alerts

We had unscheduled practice alerts three to four times a week, sometimes during daylight hours. As one or two days passed without an alert, everybody started to get on edge. We knew the alert was imminent and had to be ready to go as soon as the siren went off, so we stayed fully dressed with our boots on.

When the alert siren sounded we all ran for the aircraft at top speed My assistant crew chief was usually ahead of me out the door of his Quonset hut and I would meet him at the aircraft The first one to the aircraft hooked up the battery and started pumping open the canopy and the bomb door At the same time the engine covers and tail stand were removed by the second one to arrive After the canopy and bomb door were open our Pilot arrived He quickly climbed onto the ladder and into the front seat The Navigator was last to arrive at the aircraft First he went into Operations to grab the maps and orders from the operations officer As soon as he checked the bomb and got a hand on the cockpit ladder, he would tell the Pilot “Start the Engines or Don’t Start” If the start was given the Pilot would start #2 after giving the Navigator time to get strapped in and the canopy closed before starting #1 As the captain started the engines, black smoke from the starter rose into the sky This all took place within five minutes of the initial siren A quick engine run was accomplished, and then the engines were shut down The crews then returned to their quarters We would close up the aircraft, replace the engine covers and install new black power starter cartridges “First Smoke” was an honor among the crew chiefs and we would put $5.00 into a pool with winner taking all It was always the luck of the draw for the winner because our flight crews rotated back to Yokota every two weeks We never knew who the crew replacement would be Seconds counted and it was always frustrating when you saw others smoke before yours.

Last Day on the Pad

On April 2, 1964, K-8 was deactivated with one last alert horn, signaling all of the aircraft to start their engines and return to Yokota. As the engines started, the sky filled with black smoke. When the B-57s began taking off, we were certain that spies were sitting in the sampans along the Yellow Sea, watching the activity on the Pad and wondering who the US was going to attack.

Reporting to Clark Air Base

On April 16, 1964, we moved all of our aircraft from Yokota, Japan to the Philippines for future deployment into Vietnam For the next 4 months, we were told we would be going to Vietnam but week after week nothing changed Our flight crews continued to fly practice bomb missions and we worked on the planes as was needed The freedom we now had by not being confined to the alert Pad at K-8 was overwhelming Clark was a large base with a lot to offer We had activities from bowling, golf and even a USO show with Bob Hope I would estimate that Red, Smokey, Tipton and I played pinnacle an average of 18 hours a day at the K-8 Pad Now with all this freedom, we never played a single game The Philippines had a local beer called San Miguel that was sold everywhere The base golf course had beer on every other hole and the barracks had a bar To our delight there was an American Legion on base where the three of us went to practically every night The Legion was where we first learned about The Beatles and their music All of the entertainers were Filipino so it wasn’t until I got back to the States that I heard the real thing.

How We Got To Vietnam

President Kennedy decided to stand behind Ngo Dinh Diem, the first President of South Vietnam, in the wake of the French withdrawal from Indochina. As a result of the 1954 Geneva Accords, Diem led the effort to create the Republic of Vietnam. Kennedy was sending military advisers and Special Forces to Vietnam. By 1963, there were 16,700 advisers in South Vietnam. Although these advisers were not supposed to engage in combat, some, in fact, did. The US and the South Vietnamese army adopted the strategic hamlet program, an effort to beat the guerrillas by destroying villages that supposedly harbored them. In addition, President Diem attacked the Buddhists who opposed his anti-Buddhist repression. Some responded by killing themselves to draw the world’s attention. The USS began to think about withdrawing its support of Diem. There were indications that Diem might negotiate peace with North Vietnam. When South Vietnamese generals began discussing overthrowing him, the US did not protest. He was overthrown and murdered in November 1963. It wasn’t long before the new government was also overthrown.

Lyndon Johnson, who became President after Kennedy was murdered, increased support for South Vietnam. Johnson felt that honor was at stake. In early 1964, the Vietcong controlled almost half of the country. The US began a secret bombing campaign in Laos in an effort to destroy Vietcong supply routes. On August 2, 1964, the warship U.S.S. Maddox was attacked. Then, on August 4, the Maddox and another destroyer moved into North Vietnamese territorial waters in the Gulf of Tonkin. His was a violation of international law and an act of war. Johnson fired them; however, they hid the truth and reported to Congress that the incident constituted an attack on the United States. Congress, by a vote of 466-0 in the House and 88-2 in the Senate, passed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution on August 7. This gave the President of the United States the right to respond to attacks as he saw fit. This was the legal basis for the Vietnam War. When Congress repealed the resolution in 1970, the US continued to fight the war. In the end, President Johnson’s eagerness to involve the United States in another war cost 58,148 American lives in a War that should never have happened!

Deployment to Bien Hoa, Vietnam

With the Tonkin Gulf Resolution passed by Congress, it was now clear that we were going to Vietnam. The orders for the B-57 squadrons to deploy to Bien Hoa were sent down, only to be withdrawn at the last minute. The stress on all of us and those who had their families living with them at Clark was enormous. But these orders, and then orders rescinding them, continued, on again and off again. Finally, after both squadrons had been told to stand down for several nights, the 8th and 13th bomb squadrons were ordered to send 20 aircraft to Bien Hoa as soon as possible.

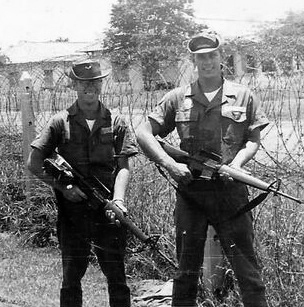

The initial deployment was well-planned and executed. It was the summer monsoon season. The jets began arriving at Bien Hoa in the darkness of night. The ceiling was down to 700 feet during a heavy rain squall. The first aircraft (RK) that landed stopped at the end of the runway, not knowing which way to taxi to the parking ramp. The following aircraft landing happened to have a loss of hydraulic brake pressure and was slowly braking. In the darkness collided it with the first. As a result, the first aircraft was a write-off. The following aircraft landing blew both tires on its landing rollout, attempting not to hit the first two planes sitting at the end of the runway. With the active runway shutting down, the remaining aircraft were diverted to busy Tan Son Nhut (Saigon), some 12 miles away. One of these aircraft crashed into the Song Dong Nai River 25 miles northeast of Bien Hoa. The reasons for the crash were never established. We were told that the plane was either hit by enemy fire or the Pilot crashed into the ground while on approach in bad weather. During the next few weeks, more B-57s were moved from Clark to Bien Hoa to reinforce the original deployment. The flight at Bien Hoa became very crowded at that time because Bien Hoa was the home of the US Navy’s A-1E & A-1H Skyhawks, Army helicopters, and the famous U-2 recon aircraft. My tent had 10 bunks, 3 Air Force Crew Chiefs, 5 Navy Plane Captains, and 2 Army Armament Specialists. Both Crew Chiefs, Ji Hendry and Hyden Weaver, were in my tent.

The B-57s were parked beside the runway in two rows, wing to wing. The planes were so close together that I could walk on top of the wings across all ten end to end. To make matters worse, we used so many bombs that they couldn’t get enough of them (from the bomb dump) during the day to load up jets for afternoon missions after the morning missions had come back. So the 500 & 750-pound 750-pound were now being stored under the aircraft wings on the ramp. There were also canisters of napalm stored on the ramp, along with hundreds of drums of Agent Orange.

Don’t Worry, Be Happy

In 1961, President Kennedy authorized the herbicide Agent Orange to be used to defoliate the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the surrounding forested land. The Vietcong used the trail to transport arms, equipment, and food from North Vietnam to South Vietnam. Between 1962 and 1971, the United States military sprayed nearly 20,000,000 gallons of Agent Orange in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. Spraying was usually done by helicopters or low-flying C-123 aircraft fitted with sprayers and 1,000 lbs of chemical tanks. In 1952, the US government had been informed by Monsanto, the manufacturer, that the chemical used to produce Agent Orange was contaminated with an extremely toxic dioxin called Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin (TCDD). It wasn’t until 1969 that this was revealed to the public. Dioxin was causing many of the previously unexplained adverse health effects that were correlated with Agent Orange exposure. TC D has been described as “perhaps the most toxic molecule ever synthesized by man.” But until then, we were told not to worry about the chemical because it was harmless! Later studies have shown that veterans have increased rates of cancer and nerve, digestive, skin, and respiratory disorders. Higher rates of acute/chronic leukemia, lymphoma, throat cancer, prostate, lung, liver, and colon cancer were found in those exposed to Dioxin. With the exception of liver cancer, the US Veterans Administration has now determined that these conditions may be associated with exposure to Agent Orange/dioxin.

Our First Mortar Attack

By dusk on Halloween, we were all back from dinner and starting to get into the beer. Our aircraft were all airworthy and had been secured for the night on the ramp. As usual, the planes sat out in the open in rows, parked wing to wing. There were no revetments between the planes; they were full of fuel. Bombs are loaded for the next day’s assignment. With no warning, at about 1:30 am on November 1, 1964, we began to hear rockets going off somewhere off base and decided it was time, once again, best to go to the bunkers just outside our tent. This happened 3 or 4 times a week, so we were not too concerned.

Nights at Bien Hoa were usually like the 4th of July. In the distance, you could see tracer rounds, an occasional bomb going off, and flares being dropped. They lit up the night sky. While in the bunker, which was only about 100 yards from the aircraft, we could see the mortar rounds beginning to drop onto the B-57s. We could only hide deep inside the bunkers, hoping it would soon end. Later in the early morning, everyone set a record, making their way to the Flightline to see the real damage. All planes were on fire, and ammo was going off. Our job was to get the bombs away from the jets before they could cause more damage. For Americans had been killed and another 72 wounded in the attack. The site of the 20 B-57 aircraft had been destroyed. Two had been burned to the point that only their engines remained relatively intact. No one C Berra had escaped some degree of damage, for Navy A-1Hs were also destroyed in the shelling.

Back to the Philippines

I was one of the lucky ones. On November 4, my second 120-day tour ended, and I shipped back to Clark Air Base for some needed R&R. My Flight Chief gave me five days off with a pass to Manila, which three of us took advantage of immediately. After leaving Manila, we continued to party at our favorite bar, the American Legion.

My Last Rotation to Bien Hoa

In February 1965, it was my turn to return to Bien Hoa. This would be my last tour. In a way, I was looking forward to seeing what improvements had been made to the base. Their Force had arranged to replace most of our destroyed B-57s with Air National Guard B-57s and crews from the States. To my dismay, nothing had changed. The light was exactly the same as before. Plans were parked wing to wing on the ramp with napalm canisters, 500 & 750-pound bombs, and 20 & 50-caliber machine gun rounds stored under the wings. They used 50,000-gallon fuel storage bladders that were initially hit with mortar and had been replaced in the very same spot. No investments had been built to separate aircraft from one another, and little or nothing had been done to make the ramp safer. The exception was the construction of new personnel bunkers near the flightline. We all knew that if there was another attack (like the one last year), it might be our last.

I was once again assigned to the night shift to clean up any unfinished maintenance from the day’s flights. The new Chiefs reported to their aircraft an hour before the scheduled takeoff, normally 6:00 am. At the end of the day, they were free to return to their tents once their plane was airworthy. Some days, they only work 8 hours, but most of the time, they never leave the flight line until after 6 or 7 pm. Sergeant Shelly Brown was a great mechanic I worked with back in Japan and Korea, and I would normally report to the flight line around 4:00 pm. We would discuss the open maintenance items with the Crew Chiefs and plan our night. Both of us were very experienced and could complete most of the work in a few hours. We cured the line and got out as fast as we could. We decided the 3 to 4 hours we worked at night compensated for how spooky it really was with no lights on the ramp except for our flashlights.

It pays to have friends.

My immediate supervisor and friend, TSGT Dewey’s two-year tour was coming to an end. H received his orders to return to the States on June 7, 1965. Sergeant Dewey had a wife and three children living at the NCO Base Housing at Clark. He was authorized to have a chaperone to assist his family in flying back to San Francisco. They asked if I was interested in being that chaperone, and I quickly jumped at the opportunity. It turned out to be the best decision I ever made. On April 8, my orders came, reassigning me from Bien Hoa to Clark to begin processing my return to the States and Eglin AFB in Florida. It was Party Time” at the American Legion.

“Things will go wrong in any given situation if you give them a chance or, more commonly, ‘whatever can go wrong, will go wrong.”

On May 16, 1965, a little over a month after leaving Bien Hoa, “Murphy’s Law” hit at Bien Hoa. At 815 m, a flight of B-57s was waiting to taxi and take off on a mission. The lead aircraft exploded, sending debris over the ramp and setting off an instantaneous chain reaction. Each of the B-57s on this mission, and others on the ramp, was loaded with four 750-lb bombs under their wings and nine 500-lb bombs in the bays. All but one had gone up. Others stacked on the runway also cooked off, as did belts of ammunition, both 50-cal and 20 mm rounds. A complete Wright J-65 turbojet engine from one of the aircraft was found half a mile away. Large chunks of metal were hurled almost a mile into the base housing area.

Captain Don Nation, one of our senior pilots from the 8th Bomb Squad, was a member of the accident board that investigated the disaster. He said, “We failed to reach an agreement on what the hell made the first plane blow up.” A time delay fuse on a 500-pound bomb was a possibility. Five 50,0000 gallon bladders of JP-4 jet fuel had gone up in smoke. When the explosions finally ceased, ten B-57s, one Navy F-8 Crusader, and fifteen A-1Es were destroyed, as were several ground support units. Twenty-seven men were killed, and over 100 were wounded. The most severely wounded were evacuated to Clark AB. One of the two line chiefs, Master Sergeant Leon Adamson, was possibly the most critically wounded, but he survived. Our other line chief, Master Sergeant Hicks, was never found, and my good friend and roommate, Hyden Weaver, was killed.

After the explosions, many generals and their staff went to Bien Hoa to see what had happened. Personally, General Westmoreland denied any responsibility for not answering numerous requests for revetments to be built to keep the aircraft separate. Little or nothing has been done to make the ramp a safer place for men and airplanes.

If we only had revetments

Our Base Commander requested revetments after the November 1, 1964, attack. His request was denied. Once again, we were told, “Don’t worry; be happy!” I was happy to sit in coach class on a Continental Air Service 707 with Sergeant Dewey and his family two days later, heading to San Francisco.

Eglin Air Force Base, Florida

On June 16, 1965, after a 30-day leave at home, I reported for my final assignment I was older and very much aware of the direction in which my career was headed Their Force provided me with great training and experience in the field of aircraft maintenance I was going to take advantage of what I had learned I enjoyed working on planes and wanted to learn more, but I knew it would not be in the Air Force I had seven months left in my four year commitment My First Sergeant called Smokey, Red, and me into his office every week for his weekly reenlistment speech He said our tour in Vietnam was completed and we would not go back We knew better Their Force had just purchased the new McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom Fighter Jets, and the plan was to send them to Vietnam The flight crews and ground maintenance personnel were being trained on the new F-4 at Eglin It was a “No Brainer” that everybody being trained on the F-4 would be headed to Vietnam Finally, the sergeant got our message, “NO WAY” He assigned us to Base Maintenance, which was like a four-month vacation I was discharged on February 25, 1966 I enrolled at the Pittsburgh Institute of Aeronautics to obtain my Federal Aviation A&P certificates and to continue working in the commercial aviation industry Red moved back to Texas Smokey got a job as a bartender in Niceville, FL just outside Eglin’s main gate It’s sad that we have never communicated with each other over all these years We each went our separate way with fond memories of our four year friendship We felt fortunate that each of us lived to remember our experiences.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

November 1, 1964: Four Americans were killed and another 72 wounded in the attack on our air base at Bien Hoa. Six of the 20 B-57 aircraft had been destroyed. Two had been burned to the point that only their engines remained relatively intact. Not one Canberra had escaped some degree of damage. Four Navy A-1Hs were also destroyed in the shelling. No one would listen to the fact that we needed revetments between the aircraft and to stop storing the bombs under the wings of the aircraft.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

Kunsan, Korea, K-8 alert pad was the best assignment, although it was cold!

The worst was Vietnam.

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect back on to this day.

Bien Hoa, working at night on the aircraft under a blanket to hide the light from our flashlights. The trust and friendship of the guys that I worked with have always stayed with me. We knew that we had to fix the aircraft and not take shortcuts. The pilots trusted us to provide an airworthy plane regardless of the surrounding conditions. I have carried that forward as a mechanic and in management at Eastern Airlines and Avsource Aviation.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

My best achievement was returning home safely and with a fantastic maintenance background, which allowed me to continue in the commercial aviation field for another 50 years.

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations, and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

I was just like thousands of other guys. We just did our job and went on with our lives. The only thing I took away from Vietnam, like so many other guys, was being contaminated with Agent Orange.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

My immediate supervisor and friend is TSGT Dewey. He always taught us the aircraft systems. He believed that we had to fully know how a system worked, not only mechanically but also from the eyes of the Pilot, to be able to troubleshoot maintenance discrepancies. Even in Korea, on the alert Pad, TSGT Dewey would hold classes in the hangar, teaching “System Description and Operation”. We covered every system on the B-57 with much discussion on “If this part failed, what would be the outcome?”.

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

Jim “Red” Hendry, Jan “Smokey” Brukowski, and I were like a family. We had been together for the entire 4 years of our enlistment. It’s weird; I joined the USAF with my schoolmate Tim Swagger. We had grown up together in Canton, Ohio, and enlisted under the “buddy program.” Once we signed up, I never saw Tim again. Red moved back to Texas. Smokey got a job as a bartender in Niceville, FL, just outside Eglin’s main gate. Sadly, we have never communicated with each other over all these years. We each went our separate ways with fond memories of our four-year friendship. We felt fortunate that each of us lived to remember our experiences.

What profession did you follow after your military service, and what are you doing now? If you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

After joining the Air Force, I attended the Pittsburgh Institute of Aeronautics to obtain my FAA A&P certificates. After graduating from PIA, I worked in Cleveland, Ohio, for the corporate aircraft division of Republic Steel. I worked as a mechanic and also part-time as a flight engineer.

After Republic, I moved to Miami, FL, and worked as a mechanic for 22 years at Eastern Air Lines. I was later promoted to the maintenance training department as an Instructor and then as the department Director.

What military associations are you a member of, if any? What specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

I currently belong to the Stuart, Florida Vietnam Veterans Association.

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

I grew up and matured in the service.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Air Force?

Get everything they offer in education. During my last 15 years in aviation, I was responsible for hiring maintenance personnel to work on commercial aircraft. Candidates with a military background were always at the top of my list.

In what ways has TogetherWeServed.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with?

I enjoy this site. I only wish more veterans were members.

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

0 Comments