Hall of Fame Major League Baseball Player, Social Reformer, famed baseball player and civil rights advocate, Jack “Jackie” Robinson became the first African-American to play in modern major league baseball.

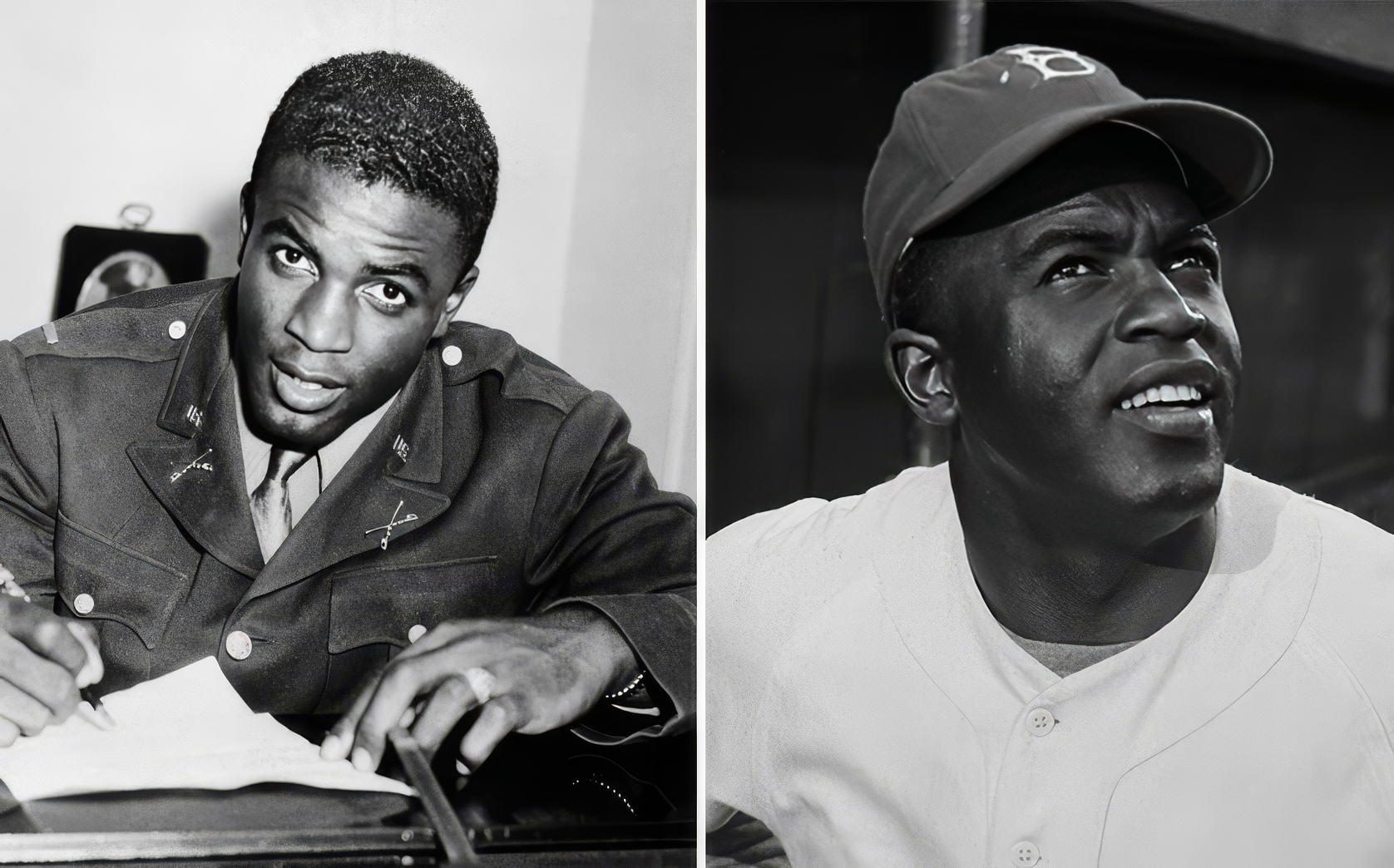

Jack “Jackie” Robinson Was Assigned to a Segregated Army Cavalry Unit at Fort Riley

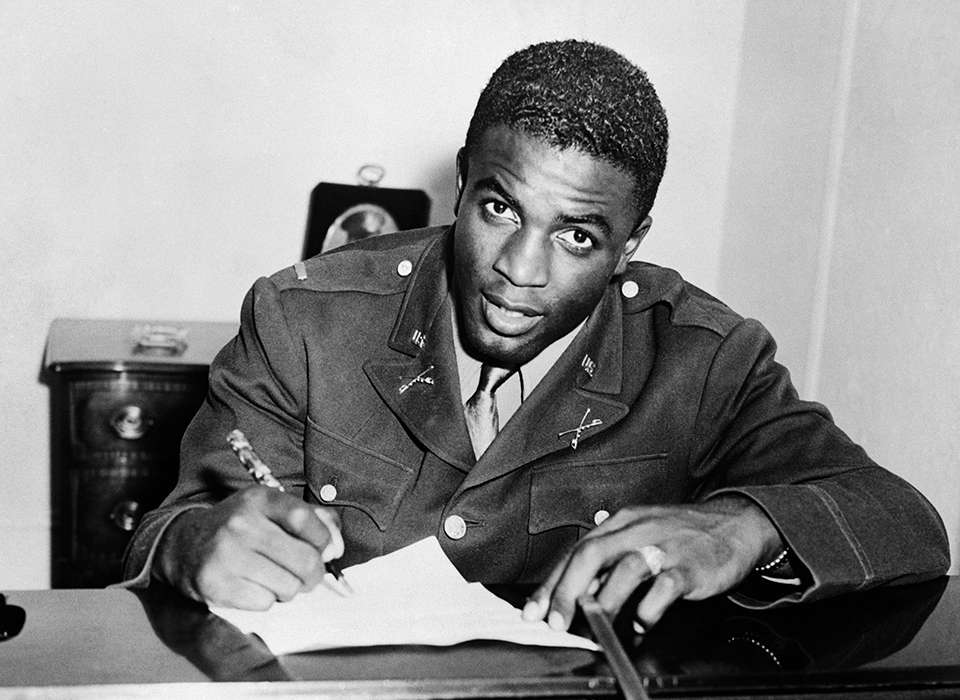

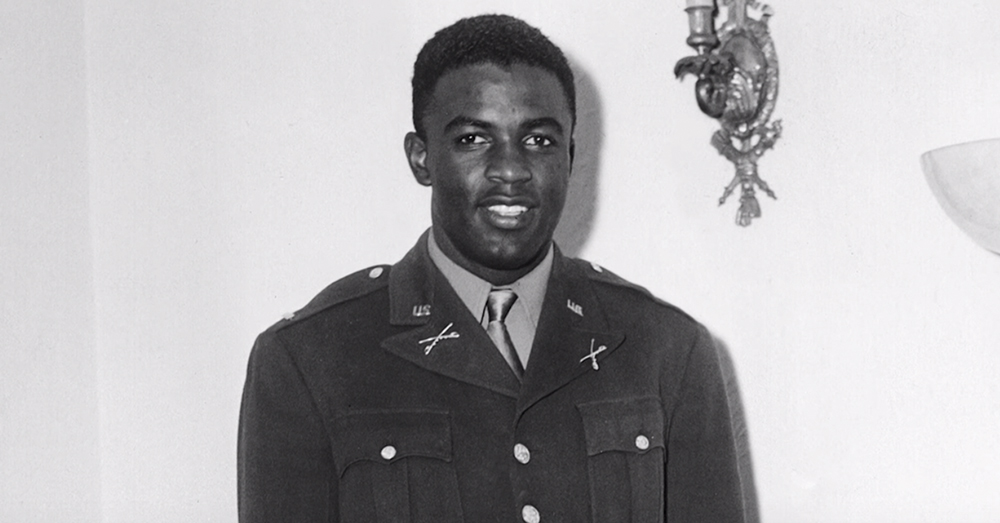

In 1942, Jack Robinson was drafted and assigned to a segregated Army cavalry unit in Fort Riley, Kansas. Having the requisite qualifications, Robinson and several other black soldiers applied for admission to an Officer Candidate School (OCS) located at Fort Riley. Although the Army’s initial July 1941 guidelines for OCS had been drafted as race-neutral, practically speaking, few black applicants were admitted into OCS until after subsequent directives by Army leadership. As a result, the applications of Robinson and his colleagues were delayed for several months.

After protests by heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis (then stationed at Fort Riley) and Truman Gibson‘s help (then an assistant civilian aide to the Secretary of War), the men were accepted into OCS. This common military experience spawned a personal friendship between Robinson and Louis. Upon finishing OCS, Robinson was commissioned as a second lieutenant in January 1943. Shortly afterward, Robinson and Isum were formally engaged.

After receiving his commission, Jack “Jackie” Robinson was reassigned to Fort Hood, Texas, where he joined the 761st “Black Panthers” Tank Battalion. While at Fort Hood, 2LT Jack Robinson often used his weekend leave to visit the Rev. Karl Downs, President of Sam Huston College (now Huston-Tillotson University) in nearby Austin, Texas; Downs had been Robinson’s pastor at Scott United Methodist Church while Robinson attended PJC. An event on July 6, 1944, derailed Robinson’s military career. While awaiting hospital tests on the ankle he had injured in junior college, Robinson boarded an Army bus with a fellow officer’s wife;. However, the Army had commissioned its own unsegregated bus line, the bus driver ordered Robinson to move to the back of the bus. Robinson refused. After reaching the end of the line, the driver backed down, summoned the military police, who took Robinson into custody.

When Robinson later confronted the investigating duty officer about racist questioning by the officer and his assistant, the officer recommended Robinson be court-martialed. After Robinson’s commander in the 761st, Paul L. Bates, refused to authorize the legal action, Robinson was summarily transferred to the 758th Battalion, where the commander quickly consented to charge Robinson with multiple offenses, including, among other charges, public drunkenness, even though Robinson did not drink. By the time of the court-martial in August 1944, the charges against Robinson had been reduced to two counts of insubordination during questioning. Robinson was acquitted by an all-white panel of nine officers. During the court proceedings, the experiences Robinson was subjected to would be remembered when he later joined MLB and was subjected to racist attacks.

Although his former unit, the 761st Tank Battalion, became the first black tank unit to see combat in World War II, Robinson’s court-martial proceedings prohibited him from being deployed overseas; thus he never saw combat action. After his acquittal, he was transferred to Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky, where he served as a coach for army athletics until receiving an honorable discharge in November 1944.

While there, Jack “Jackie” Robinson met a former player for the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League, who encouraged Robinson to write the Monarchs and ask for a tryout. Jack Robinson took the former player’s advice and wrote Monarchs’ co-owner, Thomas Baird. After his discharge, Robinson briefly returned to his old football club, the Los Angeles Bulldogs. Robinson then accepted an offer from his old friend and pastor, Rev. Karl Downs, to be the athletic director at Sam Huston College in Austin, then of the Southwestern Athletic Conference. The job included coaching the school’s basketball team for the 1944-45 season. A fledgling program, few students tried out for the basketball team, and Robinson even resorted to inserting himself into the lineup for exhibition games. Although his teams were outmatched by opponents, Robinson was respected as a disciplinarian coach and drew the admiration of, among others, Langston University basketball player Marques Haynes, a future member of the Harlem Globetrotters.

Robinson’s Life After the Military Career

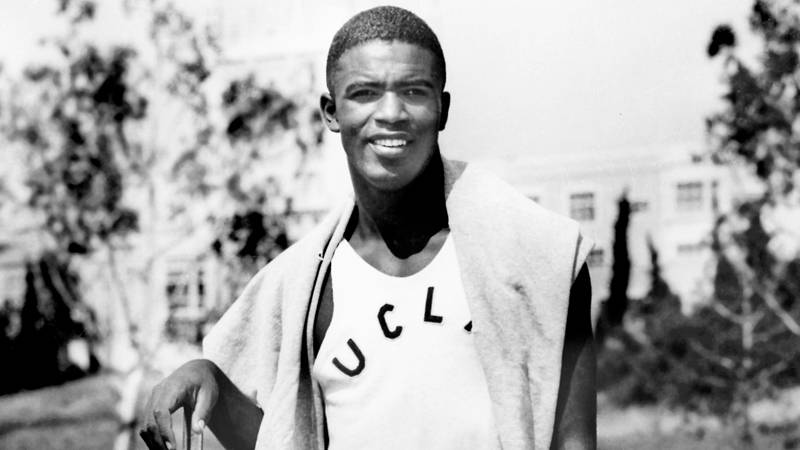

Hall of Fame Major League Baseball Player, Social Reformer. Famed baseball player and civil rights advocate became the first African-American to play in modern major league baseball. Jackie Robinson (born Jack Roosevelt Robinson) was born in Cairo, Georgia, in 1919. His single mother Mallie later moved the family to Pasadena, California, where he was raised.

As a UCLA student, Robinson earned letters in four sports (baseball, basketball, football, and track) – an unprecedented achievement. After serving in the army during World War II, he returned to civilian life to teach physical education at a college in Austin, Texas.

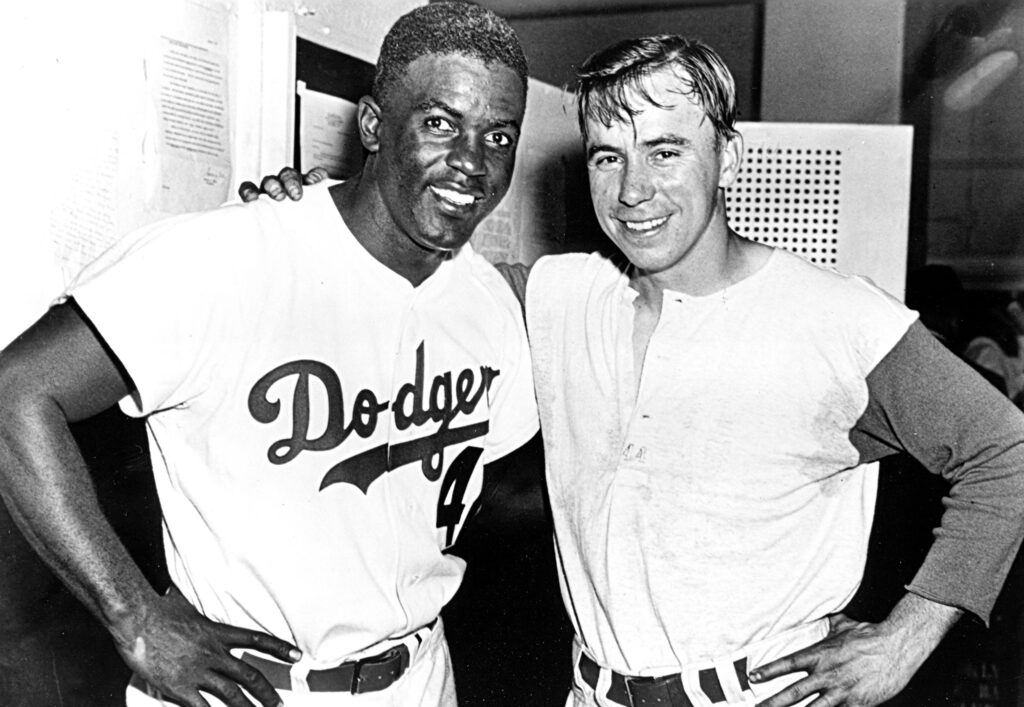

What followed marked the first steps of Robinson’s path into history. In 1945, he played in the Negro American League for the Kansas City Monarchs. On Oct. 23, 1945, Robinson and pitcher John Wright, also black, were signed by Branch Rickey (see also Rickey), President of the Brooklyn Club, to play on a Dodger farm team, the Montreal Royals of the International League.

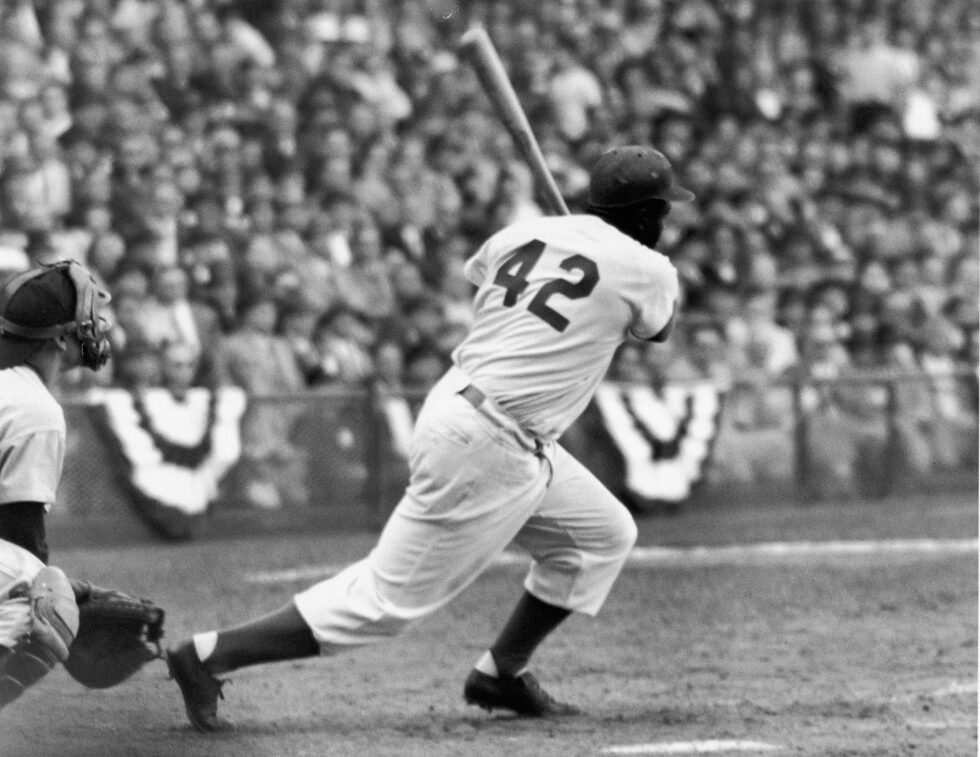

Robinson led that league in batting average in 1946 and was brought up to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 and played all ten years of his major league career with the Dodgers. He started as a first baseman but gained his greatest fame playing second base.

Robinson was an immediate success, leading the National League in stolen bases; he was chosen rookie of the year. In 1949 he won the batting championship with a .342 and was voted MVP. In 1956, Robinson received the Spingarn Medal.

After retiring from baseball in 1957, Robinson engaged in business and as a spokesman for civil rights. His career average was .311. Robinson became the first African-American inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962.

Robinson’s Final Years

Jack “Jackie” Robinson published his autobiography, “I Never Had It Made” in 1972.

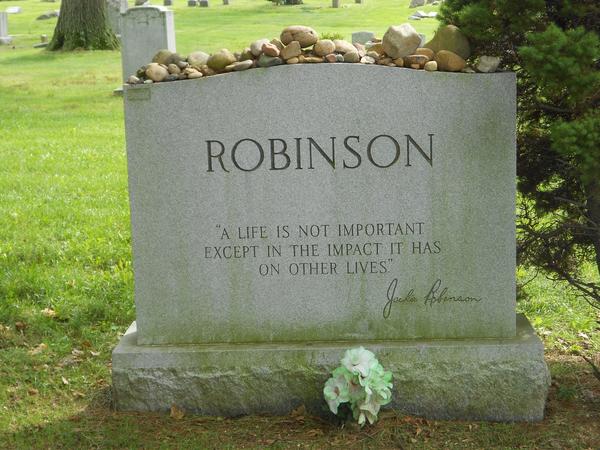

Jackie Robinson died in Stamford, Connecticut, in Oct. of 1972 at the age of 53. In 1997, Major League Baseball retired his number, 42, in tribute to a great man who was willing to suffer insult and injury for the sake of his people and his country.

Excellent article. Thank you for posting.