The 1st Marine Division, the oldest and largest active duty division of the United States Marines is perhaps best known by the nickname coined following World War II, “The Old Breed”. With a long and distinguished history, no subordinate unit better reflects the honor and best traditions of the Marine Corp than the 3rd Battalion, G Company during the Korean War. George Company served gallantly spanning Incheon, Seoul, Wonsan landings and Chosin Reservoir, pushing the limits of human endurance, but in the final days of the war would have to fight for their lives less than six miles from the site of the armistice, eerily reminiscent of World War I when soldiers were sent to their deaths up until the final moments of the war.

George Company’s Gallant Service

3rd Battalion, 1st Marines (3-1) was reactivated August 4, 1950 for a rapid September deployment to Korea. The Marines of George Company were an uncommonly diverse cross-section of American society, small towns and big cities, some rich and some poor, coal mines and farming communities, a Harvard graduate and one with a sixth-grade education, veterans of WWII, volunteers and draftees. The speed of deployment meant that basic training was foregone and replaced instead by summer camp, an effort focused on as much physical conditioning as possible prior to embarking for Korea. In many cases, the men learned to fire their weapons on-board the ship. However, for these men it has been speculated that immense patriotism developed during World War II coupled with hardships endured during the Great Depression created a generation that knew and accepted hard times, engraining a sense of hard work, self-reliance, and patriotism that would be tested on the battlefield.

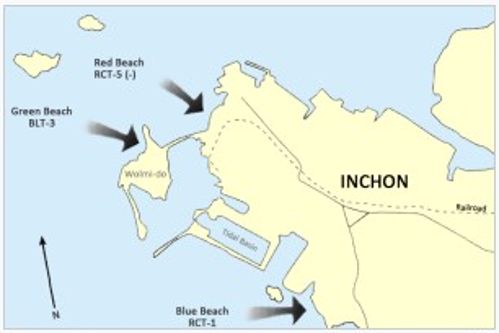

The men of George Company would be tested first in combat at Inchon, an amphibious October landing code-named Operation Chromite, with the objective of recapturing Seoul, the South Korean capital that had been lost to earlier enemy invasion. Landing through Blue Beach Two George Company attacked inland, enduring house-to-house fighting and some of the battle’s heaviest combat while suffering moderate casualties. Success at Seoul proved a major turning point in the war and caused widespread enemy retreat north, behind the 38th parallel.

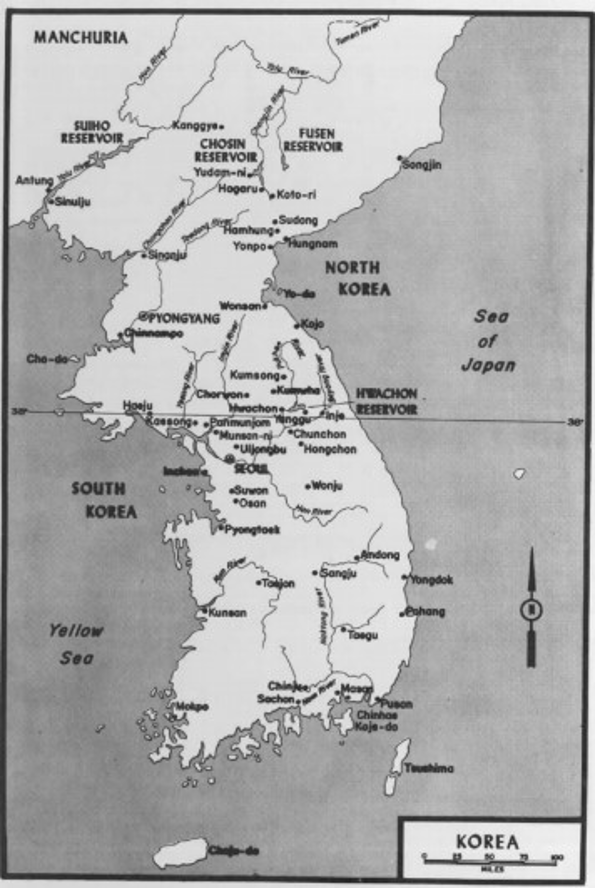

With UN forces now poised along the 38th parallel, the Chinese government warned that any breach of this border would result in the commitment of twelve divisions (120,000 troops) to reinforce North Korean communist forces. Despite this threat, UN forces including the 1st Marine Division embarked for transport and a second amphibious landing at Wonsan on the east coast of Korea, deep behind the 38th parallel. As the east prong of a pincer movement alongside US 10th Army and ordered north to the Yalu River (the Korean border with China), the Marines were to link-up with the US 8th Army advancing up the west coast. As a capstone by war planners the campaign was popularized as “Home for Christmas”- but could not be more wrong.

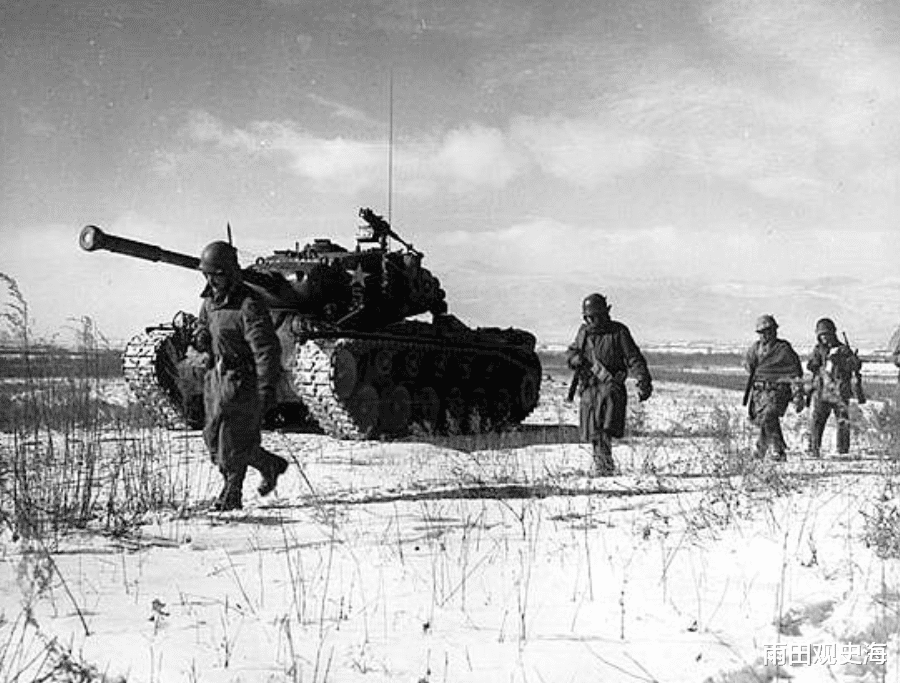

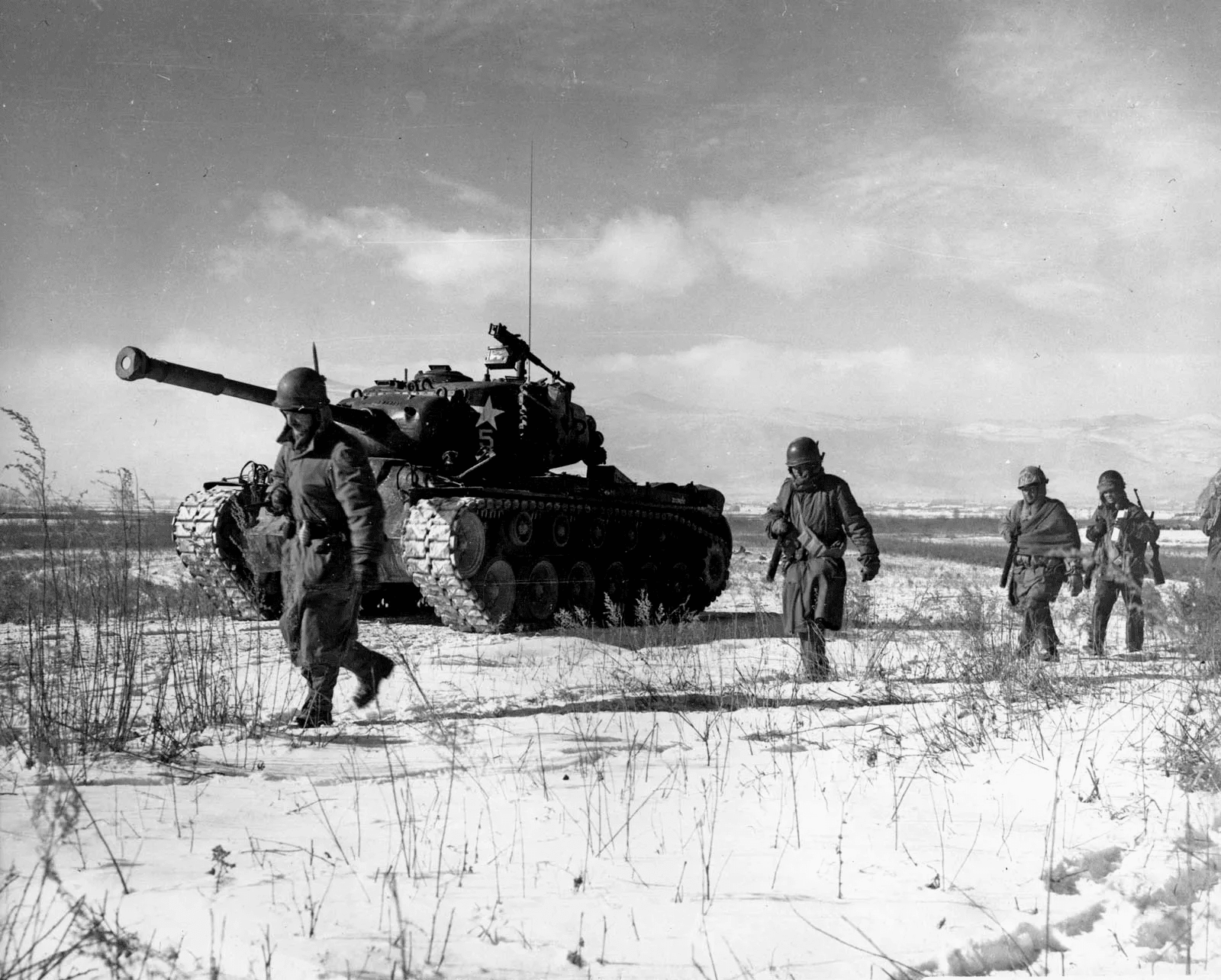

Now the end of November, Marines fought their way north along the Main Supply Route (MSR), a 15-foot-wide roadway extending 78 miles from the coastal town of Hungnam to the Chosin Reservoir through mountainous and otherwise impassable terrain. The US 1st Marine Division occupied Koto-ri and established headquarters further on at Hagaru-ri to support elements of the 5th and 7th Marines advancing on Yudam-ni. What they could not know is that two reinforced Chinese communist armies had infiltrated into North Korea weeks earlier as promised, moving at night and remaining hidden during the day. As the US 8th Army began its advance to the Yalu River the Chinese swarmed UN forces, destroying four South Korean regiments and battering the 8th Army. Ordered to retreat, 8th Army would undertake a six-week long withdrawal resulting in 10,000 casualties, and in doing so abandon forward US Marine positions to overwhelming communist forces. Following enemy engagements with elements of 5th and 7th Marines the scale of the opposition became apparent, outnumbering US forces more than ten to one. Meanwhile, as Marines and soldiers of 10th Army dug-in temperatures plummeted as far as minus 540 F, conditions not seen for over one hundred years.

Three Days Fierce Fighting of George Company

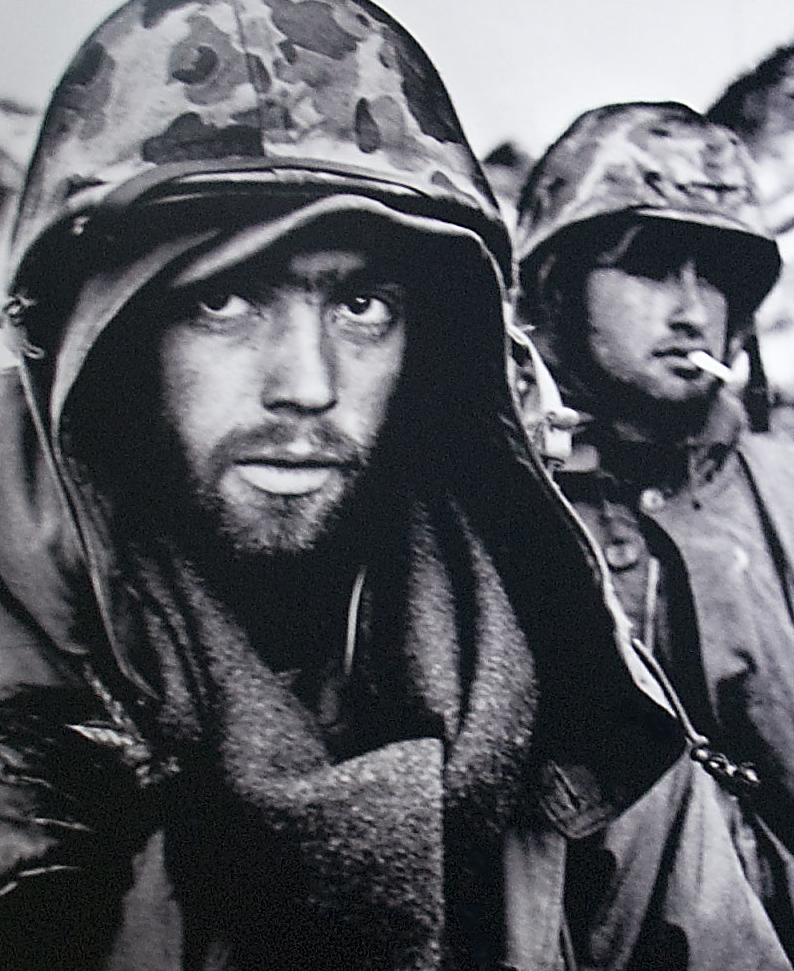

In just three days of combat the Chosin Reservoir had become a virtual massacre with communist forces well-entrenched in the high ground that encircled the reservoir and lined the MSR. The best hope for UN forces was a coordinated withdrawal extending from Yudam-ni to Hagaru-ri, Koto-ri and final extraction at Hungnam. Then located at Koto-ri, George Company was assigned to support a 250-man element of the British 41st Royal Marine Commandos in relieving Hagaru-ri, then oversee the evacuation of remaining troops. Identified as Task Force Drysdale, a convoy of 14 tanks and 150 trucks fought their way out of Koto-ri and toward certain death twelve miles away. Under continuous bombardment the task force crept forward, arriving twelve hours later at Hagaru-ri with George Company suffering 110 of the earlier 270 men killed-in-action. It is then that a LIFE magazine photographer inquired of one soldier “What do you want for Christmas?”, triggering the iconic response “Give me tomorrow”.

To ensure the MSR remained open to remaining elements of 5th and 7th Marines withdrawing from Yudam-ni, control of East Hill was vital. Once under control of US forces, communist units over ran the position and was now the scene of fierce fighting. At dawn, George Company was ordered to take the Hill and together with remnants of the original force assaulted the position, the last line of defense for Hagaru-ri. Inexplicably, the Company retained control and held for four more days against vastly overwhelming forces, enabling the evacuation of remaining marines and soldiers. Passing by East Hill George Company Marines viewed a thousand Chinese bodies littering the rocky slopes. For actions during this campaign two Marines of George Company were awarded the Medal of Honor, Captain Carl Sitter and Sergeant Harold Wilson.

Thirteen days after it began the “Home for Christmas” offensive ended with the last US troops entering Hungnam. But for George Company, the mens’ time in hell was not yet over.

Twenty miles inland from the west coast of the Korean peninsula in the demilitarized zone separating North Korea and South Korea rests a hill with large granite boulders near its crest. Spanning July 24 to 27, 1953 this hill, then known as Boulder City, was the site of the final and perhaps fiercest battle of the Korean War. Located approximately six miles from Panmunjom and the signing of an Armistice on July 27th, this position had been under attack by communist forces for several months. However, as negotiators neared an agreement the Chinese escalated fighting in an attempt to capture as much territory as possible, the potential impact of which has been argued since war’s end. In point of fact, it has been suggested that had Boulder City fallen, communists would have terminated negotiations and prolonged the war. Nonetheless, before dawn on July 24th George Company-3-1 relieved elements of 7th Marines and found itself again confronted by a reinforced Chinese regiment. Sargent James Everson remembers “the regimental chaplain was there to give us absolution- now we had good reason to be nervous”.

Within the first few hours of the battle, George Company was down to 25% of its effective strength of 209, with 24 Marines missing in action. The Chinese artillery raining down on Boulder City was relentless, causing a large number of the company’s casualties. One marine, John Comp recalls “Boulder City was just like the end of the world”. At battle’s end these three nights of combat alone earned the Marines of George Company one Navy Cross, eleven Silver Stars, a wealth of Bronze Stars and other awards for valor.

The Chosin Reservoir campaign is one of the greatest periods in Marine Corps history, heralded as upholding the highest standards of discipline and military conduct. Equally, just how the Marines of George Company retained control of Boulder City in the final days of the war is beyond our understanding. Arguably, a number of questions exist underlying decisions made and actions that were taken; why were forces at the Chosin Reservoir not withdrawn until weeks after the Communist infiltration was known, why did ROK negotiators boycott peace talks for the last two months of the war, why wasn’t a cease fire negotiated in the closing days of the war with a single article yet to be agreed… and others. Over seventy years later we will never know these answers, but what we do know is that when their country called, scores of men stood-up across the nation from diverse walks of life to be counted. Much like our heroes today, they didn’t run from the fight but instead ran shoulder-to-shoulder into danger and certain death.

Please fix link to Sgt Harold Wilson’s record. The link above directed me to Harold Wilson, PM of England. This is a comment, not a criticism.

My dad was Wallace m Hamlin

If any one out there knows information on him please let me know he past in 2001 he was part of

X Corps,George Company at the Chosin Reservoir

Does anyone remember Andrew Dirga? I’m his son. Would like to know how he won the Silver Star. He never talked about the war.

i worked with your Dad at Lawrence Livermore Lab 1976-1978. Type Andrew Dirga USMC or Andrew Dirga Recipient in your computer and you can read the citation on what he did to be awarded the Silver Star. Also he was captured and was a POW for about 5-10 minutes but ran off and escaped while the enemy was in a state of confusion. This is a story he related to me. If you order the book -This

Is War- by David Duncan. You will see your Dad leading a Squad.

George Papciak my father was at Chosin anybody remember him.

Attended a funeral today for a 92-yo vet of George company, 3rd battalion, 1st marines. Abnor Richard (aka Dick) Williams. Fought at Cosin and beyond.

I agree with John Gregg’s comments. Sgt. Wilson received his medal of honor for action on Hill 902 during the Chinese Spring Offensive in April 1951.

The second Medal of Honor during the Chosin Campaign was awarded to Pfc. William Baugh on Taskforce Drysdale. 29 November 1950.

i was in g 3 1 on the imjin34th draft

Hello everyone! My Dad’s uncle served in the Korean War. His name was Private First Class Rivera-Diaz Victor Manuel (native from Puerto Rico), he was assigned to Company G, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, 1st Marine Division. He was KIA on Nov. 24th 1952. That’s all the information we have about him. I would love to learn more about him.

I can help you with the information on Victor M. Rivera-Diaz.

Hello Ms Hensley, Jose Grau. When I posted about my uncle, I never thought I would actually hear from anybody. What sort of information you have?

Thank you,

Jose

My Dad served with Victor and has been wanting to visit with his family for 70 years!

my dad was Roberto M. Soto. He serviced in George Company. did anyone serve with him or did they know him?

My father was Dan Hautzinger : He was in the bloody george but never spoke of

it. He was one of only 6 men in his platoon to survive. Heres part of his

obituary. On January 16, 1951 he enlisted in the United States Marine Corps,

was a member of the 1st Marines of the 1st Marine Division. He fought many

close battles often leading his squad as point man. He was proud to serve his

country .. Serving in Korea, he was awarded the Purple Heart and the Purple

Heart with Gold Star, the National Defense Service Medal, Korean Service Medal

with three Bronze Stars, the United Nations Service medal and the Presidential

Unit Citation-Republic of Korea medal. He was honorably discharged on January

14, 1954.

My father served in George Co. with Dan Hautzinger.

My name is Donald Wiebort my Father Donald Wiebort survived that battle

My Father in Law was Called Menehune served in Korea 1950 to 54 and then Vietnam. He served for 30 years. If any Korean War vets remember him he would love to see or meet with you all. He lives in Las Vegas. He just within the last 10 yrs started talking about his Time in Korea. His real name is James K Tom

My father Rodger Reynolds was there but never spoke about it he passed. In 1982. I have been trying to find any information I can I have been told the records were destroyed at an archive facility fire or flood. I am also a former Marine. Thank you for any information

My father was Robert “Bob” Parenti. Company 3-1 Korea. Does anybody remember him? Many thanks.