On January 21, 1953, during Korea’s Winter War. Night fighter team “George” of composite squadron three (VC-3) was operating from USS Oriskany (CVA-34) in the Sea of Japan.

The Night Fighter Team Filed a Misleading Report

Excerpt from combat report:

Saw 75-100 trucks on G-3, seven trucks seen damaged. Meager to intense AA, much rifle fire was seen. The plane hit by 30 cal. Item – Lt. James L. Brown, USNR assigned F4U-5N #124713. One-night landing aboard without incident. 2.6 combat hours.

Combat strike report comments, like that above, were distilled from the intelligence officers debriefing of pilots from returning strikes and later filed with higher command. They, in turn, used these reports from the pilots who flew the combat missions, and reported what happened, to plan later strikes, select subsequent targets, and subject to political considerations, the overall conduct of the war. Seldom did they tell what happened.

It was just as well. Here is what really happened that night.

The Night Fighter Team Waited to Launch

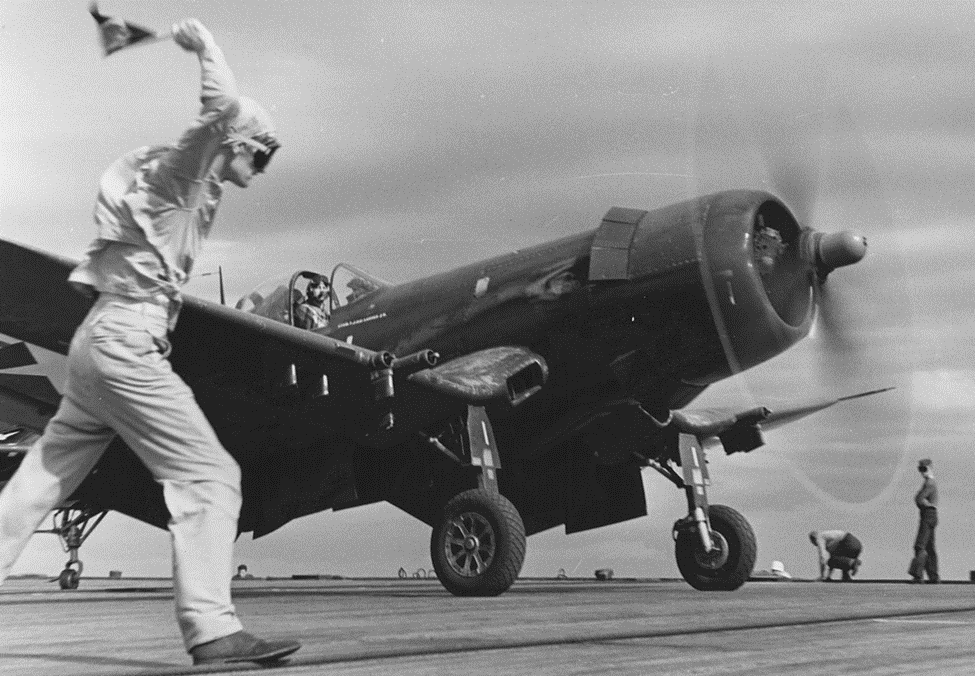

Two-night fighters of team “George” were on the catapult and already connected. Two others were waiting behind them. They would be launched as the fleet had completed turning into the wind and attained sufficient speed to launch planes. On one of the other carriers, its night fighters were going to be on a similar night mission and awaited their launch as well. The third aircraft carrier was at “flight quarters” and available to land planes should there be an emergency. Behind and to the right of each carrier was a “plane guard” destroyer and an airborne helicopter whose jobs were for rescue should a catapult fail, and one of the catapulted planes crash into the icy water.

The flight leader and his wingman were each given the signal for maximum power. They would be catapulted close together, one from each side of the flight deck, to immediately join in formation after becoming airborne and continue towards North Korea.

It would still be daylight when they reached Korea. The North Americans planned to stay out of anti-aircraft range until it was dark on the ground and would fly in a loose two-plane section at low altitude down the valleys between the surrounding peaks to look for any North Korean trucks, tanks, troops, or other enemy traffic that might be on the roads. Then, kill them.

The Night Fighter Team Lost a Plane

Suddenly, as both two remaining planes were at full power ready to be catapulted, smoke billowed from one of their engine cowlings and exhaust stacks. Thick black oil blown back from the propeller blast streamed down the side of the fuselage. The pilot immediately shut down his engine, unlocking his safety belt and shoulder harness as he hurriedly exited the cockpit.

Abandoning his plane, he ran behind it across the flight deck to the safety of the catwalk at its edge to the steel walkway a few feet below. The propeller had hardly stopped turning before plane handlers hurriedly disconnected the plane from the catapult and pushed it to the flight deck elevator. It would be repaired later on the hangar deck.

In the meantime, Grumman F9F-5 Panther jet fighters were returning early from late afternoon missions. They had made repeated attacks on a difficult and heavily defended target. Low on fuel, they needed to land immediately. Because the two other scheduled night pilots had already been catapulted and departed on their mission, it was quickly decided to send the remaining pilot from the fighter squadron on a single plane mission into North Korea.

Had he not been immediately catapulted, Oriskany’s plane handlers would have been required to detach his plane from it. Then, rapidly clear the deck to take jets aboard by taking his plane down to the hanger deck, land the jets, rearrange or re-spot other planes on the deck and later send the originally scheduled two planes out late on their mission. That is, if the damaged plane could be repaired on time and became flyable.

KA-WHOOM! He was immediately catapulted alone into the late afternoon sky.

The Night Fighter Team Flew Into Daylight

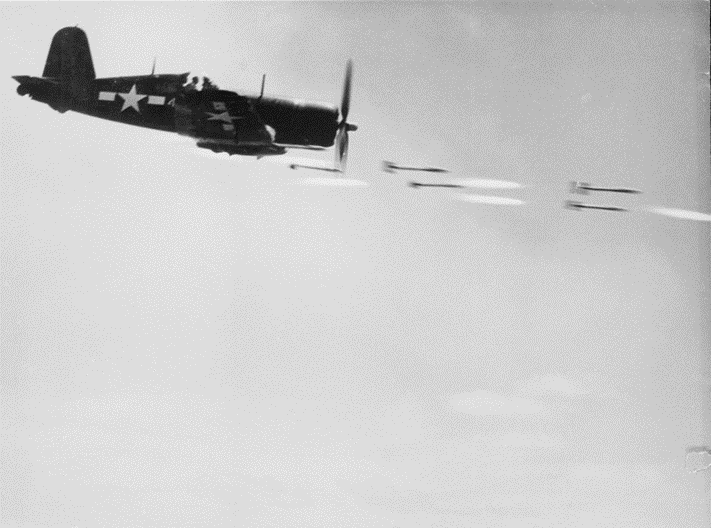

Because the jets returned before their scheduled recovery time, that forced the night fighter’s early launch. It meant they would arrive on target earlier than planned. Night fighters were forbidden to arrive over the target area during daylight hours because enemy gunners on the ground readily recognized the special random configuration built into the right-wing of the F4U-5N Corsair.

After Lt. Brown had been hit by anti-aircraft fire on a volunteer, day spotting mission for the USS Los Angeles, night fighters flew only at night. With their hatred of the night pilots who strafed, burned, and bombed after dark, every enemy gun available was trained on them anytime one of those planes were recognized.

Because of this, should a night fighter arrive early or during daylight hours, the pilot was ordered to remain at sea and out of anti-aircraft range until it became dark on the ground. Only then was he to continue and conduct his assigned mission.

That misguided operational instruction caused fatalities that Brown did not accept. He knew from experience that he would be seen by an enemy radar system and plotted on their communication grid. This would have alerted them to his exact track and arrival time. Every anti-aircraft gun in the area would have been ready and pointing right at him as soon as he crossed the coast. Like many pilots, he ignored this direct order, drastically changed course, and entered North Korean airspace far from his briefed target.

The late afternoon sun was brilliant, and the sky without any clouds when he reached Korea. Although freezing that time of year, with the normal bad weather regularly experienced at sea, this was a welcome change. The temptation was just too much for him. Korea was going to be seen personally, low, and up close. During daylight.

The Night Fighter Team Pilot Met a Brave Soldier

Out of radar operator range from both the American Navy, the Korean enemy, and while still out at sea, he dropped down low over the waves to cross the coast a few feet over the sand. He was in North Korean airspace. No anti-aircraft fire found him, nor attacks from airborne radar-equipped foes. “Hot damn!”

North Korea in the backcountry looks much like Scotland because of its low mountains, deep valleys, and sparse trees. Patches of snow remained in the low spots and gullies. It looked like the scene on a picture postcard with no haze or the smoke and fire of war. Low, blue-tinted mountains in the distance, slightly rolling hills where he flew, and sunlight reflecting off the remaining snow with the promise of peace and better days, war seemed far away.

In the distance, a road beckoned to be explored just for the fun of it. He flew lower, below treetop level, and maneuvered the heavy bomb-laden fighter plane over the roadway. Experiencing the sheer pleasure of flight without trying to kill someone or fly into an anti-aircraft nest or mountain in the dark, he began to relax for the first time in months.

If this was against orders to not “hedge hop,” who was to know? No one knew where he was anyway. For that matter, neither did he. As his plane continued a few feet above the roadway, over the crest of a low hill, then down and up the other side, he was startled to see a company of troops walking in the middle of the road.

The Night Fighter Team Pilot Faced One Man’s Defiance

As he roared past a few feet over their heads, some who had heard him coming dived into the ditches. Then, rolling on their backs, they began firing their weapons at him as he passed. Later, he would remember clearly seeing their muzzle flashes. All the enemy soldiers dived for the ditches except one. He simply stood where he was in the middle of the road, put his rifle to his shoulder, and commenced firing. He continued to stand alone in the road, repeatedly firing at the oncoming enemy aircraft flying towards him at eye level. Brown could clearly see the muzzle flashes.

As the aircraft passed a few feet over the soldier’s head, he could not believe what he had just seen. He commenced a gentle left turn back to the road, reduced power, and lowered his flaps to fly as slowly as his ordnance load would allow looking at this man again. Then, following the same flight path, he made a second approach on the lone soldier standing in the middle of the road. He found himself fascinated, counting the enemy soldier’s muzzle flashes.

They were eye level as the airplane again flew up the slight hill at 180 knots towards the soldier who stood erect in the road and continued measured fire, one shot at a time.

Just like the story of a snake hypnotizing a bird, Jim could not take his eyes off the soldier. Firing at him! Unbelievable! Flash! Thunk. Flash! Flash! Thunk. Ping. Flash!

With all the firepower available at his command, it was sufficient to destroy a good-sized town, much less one man. This was truly incredible. Amazed by what had just happened, “Goliath” continued to his night bombing mission without firing a single shot at that lone “David.”

Brown’s plane carried a full belly tank with 200 gallons of high-octane aviation gasoline that had he dropped, it would have engulfed the entire company of soldiers in flames. His straight wing cannons housed 800 rounds of high explosive incendiary 20-mm shells that upon impact explode with a green flash and are as destructive as hand grenades. Also, he carried six 260-pound fragmentation bombs with devices on the fuses that make them explode three feet above the ground and a 500-pound general-purpose bomb that was sufficient to take out a sizeable bridge or blow over a locomotive. One burst from his cannon could have killed the entire company.

The man must have been insane or infuriated. He simply stood erect in the middle of the road and continuously fired his rifle at the plane.

The Night Fighter Team Plane Came Back Shot

The remaining mission was as recorded in the combat report given to United States Navy debriefing officers. Jim did later damage or destroy seven trucks with bombs and cannon fire, probably killed upwards of 100 or more troops in them (if trucks did not explode, they were likely carrying troops as well as supplies because they were never empty). He dodged in and out of the anti-aircraft fire as reported and still wondered about that North Korean soldier who was the bravest man he ever saw. Maybe that lone North Korean soldier was just fed up with war, or just like Jim, fed up with war too.

The following morning, after landing back aboard Oriskany late that night, he personally inspected his airplane for combat damage as he did after every mission. However, this time he found “George” team mechanics looking at bullet holes and commencing to remove the engine cowling. The left-wing flap had already been removed for repair.

There were holes in the engine cowling that appeared not from anti-air or air to air confrontations but from a 30-caliber rifle bullet. These were straight from and level with the aircraft’s nose, which indicated he was hit when he was flying below the level of the soldier on the road. Some bullets had gone between the blades of the four-bladed propeller, entered the cowling just below eye level, bent a cylinder fin, and then bounced off the carburetor. An inch, either way, would have brought the plane down.

As he had passed overhead, the soldier, or another in the ditches, put a bullet through the left flap. Had it been twelve inches to the right, that would have put it in his body.

The Corsair was designed for air to air combat with other planes. It carried no armor plate under the pilot. The armor plate was only at the pilot’s back.

Jim, no doubt, had a guardian angel.

Maybe the Korean soldier did too.

Read About Other Battlefield Chronicles

If you enjoyed learning the story about the The Battle of Khafji, we invite you to read about other battlefield chronicles on our blog. You will also find military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

0 Comments