Throughout the Vietnam War, the United States estimated that more than 2,500 American service members were taken prisoner or went missing during the Vietnam War. North Vietnam acknowledged only 687 of those unaccounted for. Most of them were returned during Operation Homecoming in 1973 after the Paris Peace Accords ended U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Of those 687, only 36 U.S. troops managed to escape their captors in North Vietnam and Laos. Of course, there were other attempts, but only those 36 made it back to American lines. One of those successful attempts was made by James N. Rowe, a Special Forces officer who would later use what he learned to help future American escapees.

Biography of James Rowe

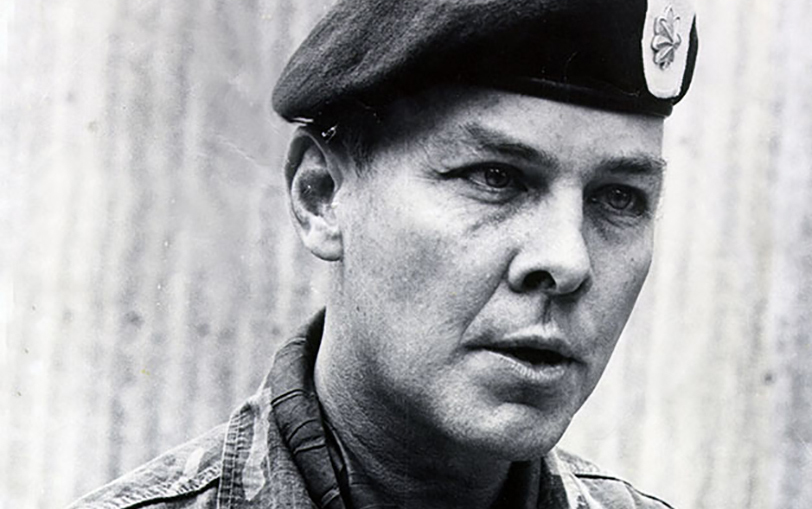

James N. Rowe was a Texas native who attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point after graduating from high school in 1956. He earned a commission in 1960 and by 1963 found himself in South Vietnam, acting as the executive officer of Detachment A-23, 5th Special Forces Group.

It was there that James Rowe commanded his A-Team in training Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) soldiers in the Mekong Delta. The goal was to train these South Vietnamese locals to bolster the South’s defenses and counter the growing influence of North Vietnam’s Viet Cong guerrillas.

While training the CIDG troops, Rowe and two of his fellow West Point classmates accompanied troops trying to clear the village of Le Coeur of VC activity. The CIDG troops moved into a VC stronghold in the U Minh Forest. As they moved to attack the command post, they found it empty and moved deeper into the dense jungle to pursue the enemy.

But it was an ambush. They underestimated the Viet Cong in this area and found it was a Main Force battalion. The CIDGs and Green Berets fought for eight hours but were overrun. Rowe was captured during the fighting after just three months in-country.

James Rowe Became a Prisoner of War in Viet Cong

Rowe would spend the next 62 months in captivity in the dark U Minh Forest, in a bamboo cell three feet wide, four feet long, and six feet high. He fought off dysentery, fungal diseases, and terrible psychological and physical torture for the duration of his stay in the prison.

The Viet Cong initially tried to interrogate him, but he claimed he was a drafted civil engineer, a ruse he was able to maintain until the VC discovered his true identity as an intelligence officer. By the time they discovered who he really was, the information he had would have proven useless. Angered at the missed opportunity, the VC sent him to be executed in the U Minh Forest.

Rowe had made a number of escape attempts before this final one. Each time, he was either recaptured or coerced into returning by threats of violence toward his fellow POWs. This time would be different. The communist guerrillas led Rowe into the dark jungle for his coming execution. As they walked, a flight of UH-1 Iroquois “Huey” helicopters flew overhead. As his captors watched them fly by, he used the moment as an opportunity to escape.

He overpowered one of the guards, shoving him down to the ground, and made his getaway. Rowe ran into a clearing of the trees, waving at the Hueys. Dressed in the black pajama uniform of a Viet Cong, the Americans almost opened fire on him, but one pilot noticed his thick beard, one a Vietnamese man could not grow. The pilot realized he was an American.

After realizing who he was looking at, the Huey pilot dropped down, scooped Rowe up, and flew him to safety. The year was 1968, and Rowe had been promoted to Major while he was held captive.

Rowe’s Life after the War

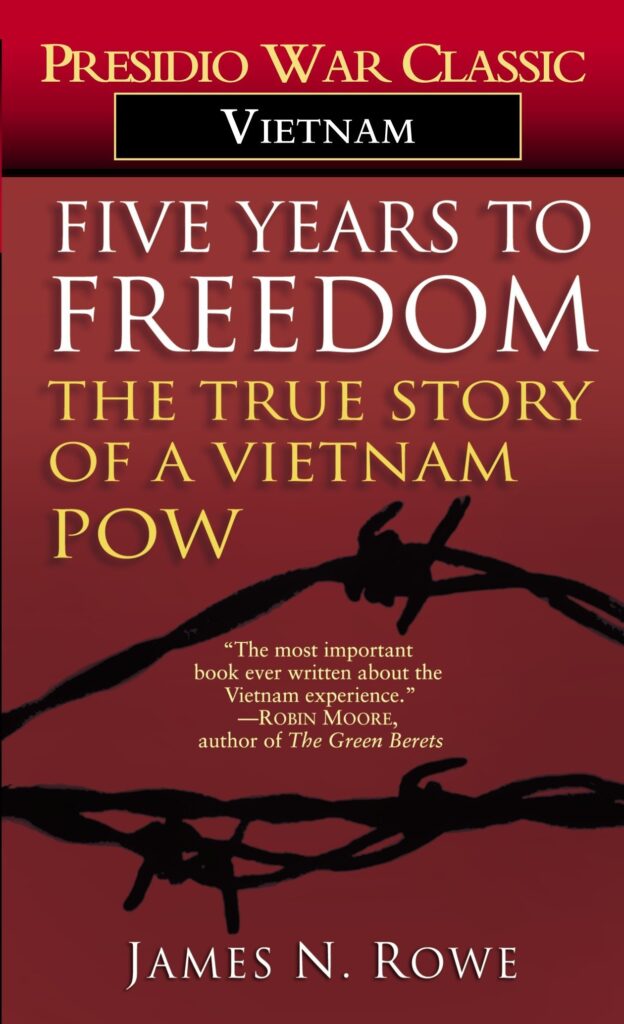

He later served as the Army’s Adjutant General for the POW/MIA program and published his book, “Five Years to Freedom,” a retelling of his time as a prisoner, based on a diary he kept while in captivity. He left active duty in 1974 but remained a reservist in the Army.

When the time came for the Army to develop a program of training for soldiers who were in danger of being taken captive, they looked to then-Lt. Col. James Rowe to design it. His training and time as a prisoner, along with his numerous escape attempts, gave him insight that few others could offer.

He developed SERE, Survival Evasion Resistance Escape training, used even today for special operations troops and aircrews from all service branches. It is still considered one of the most important training programs for military personnel.

In 1987, Rowe was reassigned to assist the CIA and the government of the Philippines with infiltrating the New People’s Army (NPA), a communist insurgency that threatened to topple the government in Manila and replace it with a communist regime. Sadly, he was assassinated by the NPA in 1989.

James Nicholas Rowe, a recipient of the Silver Star, Legion of Merit, Bronze Star, and Purple Heart, was buried in Arlington National Cemetery later that same year.

Had the opportunity to meet Nick while he was stationed at the Defense Language School at Monterey, CA. We had opened the Vietnam Veterans Outreach Center and he attended the grand opening. What a neat guy. Shortly after we met, he was assigned to the Philippines and was murdered by the Communists, I suspect the NVA issued a contract on Nick because he embarrassed them with his escape and the follow-up teaching the SERE program. God Bless Nick Rowe and his family.

He and I shared an office after he was released to active duty. Giant of a man, courageous to a fault. Devastated to learn af the circumstances of his death, especially after all he had endured. RIP, Nick!

As an MI Major, I commanded the MI Company, 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne) from 81-83. Early on in my time as Commander, LTC Nick Rowe was assigned to my Company and he was occupying one of my slots but he was working in the JFK Special Warfare Center & School, and had not seen him since the day he arrived to inprocess. So I started asking questions about who was LTC Nick Rowe and soon learned that he had been a POW for over 5 years and that he was assigned to the JFK Center to write the US Army’s Survival Evasion Resistance and Escape (SERE) Doctrine. I attended two of COL Nick Rowe’s POW presentations and was truly amazed at what this man endured as a POW and that he tried to escape 3 times and was recaptured every time. I soon learned what a tremendous asset Nick Rowe was to SERE Doctrine and Training. And I learned during the time he was assigned to my unit that I deeply admired and respected Nick Rowe and we became friends while he was assigned at Fort Bragg. I was surprised to hear about the Ambush that occurred in the Philippines. I know that while I continued to serve as an MI Officer in various Airborne and Special Operations units I learned what a major impact COL Nick Rowe had on the US Army and SERE Doctrine and Training. He is a true American Hero and an Army Officer that has helped so many military service members by using his SERE doctrine and training to escape and stay alive while in captivity. RIP – COL Nick Rowe.