Robert Eugene Bush wasn’t old enough to join the Navy when the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. He was still in high school. His neighbor in his hometown of Raymond, Washington, was a Fireman aboard the USS Arizona.

“He’s still on board the Arizona,” Bush said in a Veterans History Project Interview.

Bush could barely stand the wait to join the war. He wouldn’t be old enough until his 17th birthday in the Fall of 1943. He and a friend from school dropped out and enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve.

“We just wanted to be part of it,” he said. “A little of it was adventurous, but the rest of it was to get even.”

He would only be in the military for one year, six months, and 22 days, the shortest tour of duty of any of the Medal of Honor recipients in World War II. But the battle he would fight to earn the medal would be one of the war’s biggest and deadliest: the Battle of Okinawa.

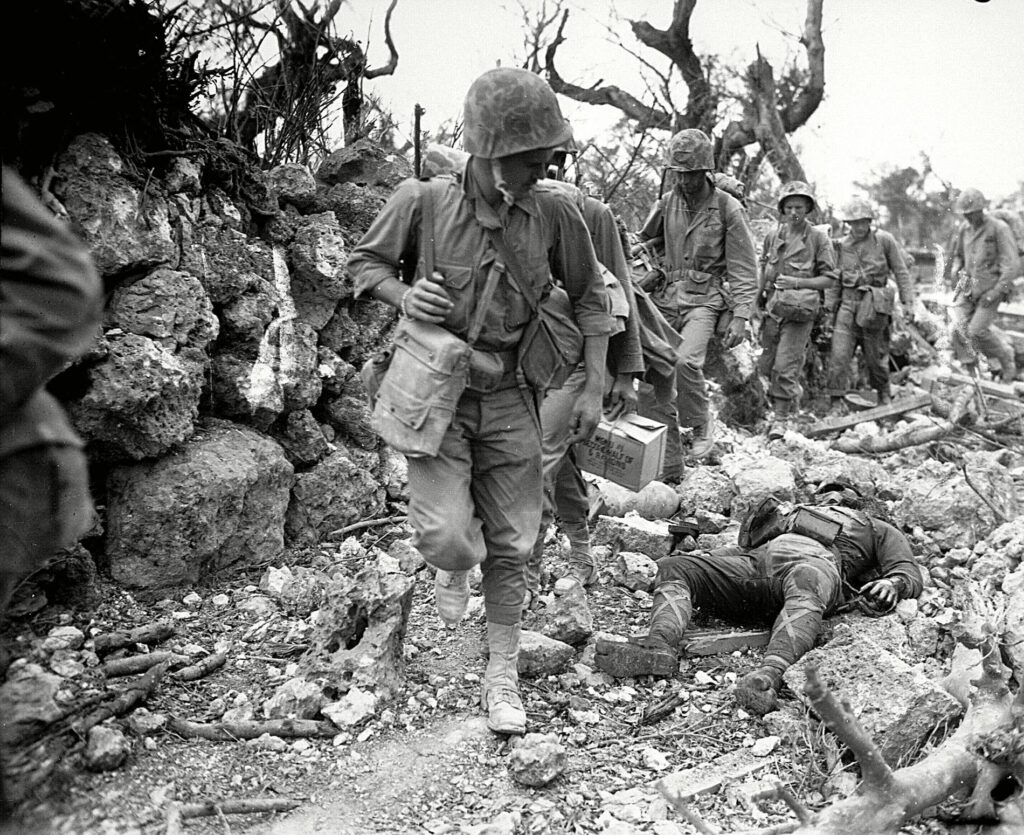

For 98 days, U.S. Army soldiers and United States Marines fought the Japanese defenders on Okinawa’s 463 square miles. It has come to be known as the “Typhoon of Steel,” given the fighting’s viciousness on the island.

The fight for Okinawa began with a massive naval bombardment that would become unnecessary, as the Japanese defenders allowed the U.S. to make its way to shore virtually unopposed. But the 130,000 fortified Japanese troops were lying in wait for them.

When the enemy did attack, the fighting was brutal.

Okinawa was going to be the primary Army, Navy, and Air Forces staging point for Operation Downfall, the Allied invasion of the Japanese home islands. Failure was not an option for the Americans.

Robert E. Bush was a young sailor who signed up to be a Navy Corpsman after basic training. He practically grew up in a hospital, as his mother was a single mom and nurse in his hometown. Bush thought he might be working in a hospital, a job he was comfortable doing, given his upbringing. He didn’t even know the Marine Corps had Navy Corpsmen.

Once he learned about the job, he signed up to be one. After four months of combat and field medicine training, he was shipping out to the Pacific. He was assigned to G Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, who were still recovering from the invasion of Peleliu.

He trained for an amphibious landing with the Marines. Over and over, they stormed the beaches of Guadalcanal, which the U.S. had taken in 1942, preparing for their next island invasion, which they all believed would be Formosa. They were wrong.

Bush soon found himself aboard an LST with 500 Marines in the waters near Iwo Jima, which had fallen to the Americans just days before. The next day, he was off the coast of Okinawa, one of 1700 ships there to make the landings on the island.

“It gave you a certain amount of confidence,” Bush said. “There was an innumerable amount of ships and landing craft, so we thought this would be a piece of cake.”

U.S. Navy leaders weren’t so sure of that, so it unleashed the largest naval gunfire barrage to support an amphibious landing of the entire Pacific War.

The bow doors opened, the armored amphibious tractor came out, and the Marines went ashore just north of Bolo Point on Okinawa. They were expecting to have to climb a sea wall, but the USS New Jersey had already leveled the wall.

They also expected untold beach hazards, traps, and thousands of Japanese soldiers, but he says there wasn’t a soul there when they landed. They quickly made their way to the airfield to find the Japanese planes still on the ground. The Marines made their way to Shuri Castle before the enemy started to show itself.

Robert Eugene Bush was on Okinawa for 32 days, and by the time they’d reached Shuri Castle, the platoon had lost half of its 58-man strength.

“It’s hard to understand the number of deaths there was on Okinawa,” Bush said. “310,000 people died in 82 days, but of the wounded, we were able to save 94% of them. We lost 13,000 Marines there, but it was only 6% of the wounded.”

Bush’s company of Marines were next assigned to take Kunishi Ridge, a fortification the Army had attempted to take for three weeks to no avail. His platoon leader, Jim Roach, broke from the lines to reconnoiter a hill that they were supposed to take that morning.

Navy Corpsman Robert Eugene Bush In Battle of Okinawa

When Roach got to the hill, the Japanese poured out of the hill and peppered him with small arms fire. The Marines told Bush where their leader was, far from friendly lines.

“The rules of the road is, if it impairs my ability to do my job as the Corpsman, I can’t go,” Bush said. “But if I think I can get out there, get him back, can save him, then I go.”

The Platoon Sergeant told Cpl. Bush, he didn’t have to go this time. But Bush asked for two Marines to accompany him, one to run in front and the other behind. The Marine in front was killed right away. The Marine behind Bush was gone by the time he reached the wounded man.

Bush began treating Roach with whole blood but soon saw Japanese soldiers pop their heads up out of the ridgeline. The Corpsman grabbed his officer’s carbine and fired off a shot, still holding the blood bottle. Eventually, the officer began to recover, and Bush kept shooting.

“I didn’t look at it as anything more than I’d been doing the 31 days before,” Bush said.

Robert Eugene Bush ordered one of the Marines who had left with Roach to take him back to the main force while Bush covered their exit. Suddenly, a Japanese hand grenade landed next to Bush. The explosion took out his right eye. Two more landed next to him, and he took the brunt of all three.

The leather shoulder holster for his .45-caliber Colt M1911 likely saved his life. He had no scarring where the holster protected his underarms.

“By that time, I’m really mad,” he said with a laugh. “I knew if I turned around, I was dead, so I took his carbine and an M1 from a fallen Marine and went right around the hill and up after them.”

By the time he climbed the hill, he could barely see from his left eye, but he was looking at the backs of the Japanese soldiers who had just thrown three hand grenades at him if you asked Cpl. Bush how many he killed, he’d say he killed every one of them he could find.

He made his way back to the lines, bleeding from multiple wounds and missing an eye. He finally collapsed, trying to walk back to an aid station.

It would take a battalion of 800 men to take the hill. Bush was presented the Medal of Honor by President Harry S. Truman at the White House on Oct. 5, 1945, for his actions on Okinawa. At age 18, he was the award’s youngest-ever recipient.

After the Battle of Okinawa, Robert Eugene Bush recalled talking to the now-famous conscientious objector and Army medic Desmond Doss, a fellow Medal of Honor recipient who saved lives on Okinawa while completely unarmed. He credited God with seeing him through the battle.

“Desmond,” he told Doss, “With the help of God and a few Marines, I got through.”

Robert E. Bush died on Nov. 8, 2005, at age 79.

Robert E. Bush’s Official Medal of Honor Citation

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as Medical Corpsman with a rifle company, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Okinawa Jima, Ryukyu Islands, 2 May 1945. Fearlessly braving the fury of artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire from strongly entrenched hostile positions, Bush constantly and unhesitatingly moved from one casualty to another to attend the wounded falling under the enemy’s murderous barrages.

As the attack passed over a ridge top, Robert Eugene Bush was advancing to administer blood plasma to a Marine officer lying wounded on the skyline when the Japanese launched a savage counterattack. In this perilously exposed position, he resolutely maintained the flow of life-giving plasma. With the bottle held high in one hand, Bush drew his pistol with the other and fired into the enemy’s ranks until his ammunition was expended.

Quickly seizing a discarded carbine, he trained his fire on the Japanese charging point blank over the hill, accounting for six of the enemy despite his own serious wounds and the loss of one eye suffered during his desperate battle in defense of the helpless man. With the hostile force finally routed, he calmly disregarded his own critical condition to complete his mission, valiantly refusing medical treatment for himself until his officer patient had been evacuated and collapsing only after attempting to walk to the battle aid station.

His daring initiative, great personal valor, and heroic spirit of self-sacrifice in the service of others reflect great credit upon Bush and enhance the finest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.

I had the pleasure of knowing HM Bush. He was a humble man and a true inspiration to all who knew him.

The principal photo shown for this article is NOT Robert Eugene Bush. Bob Bush, for one, lost his left eye on Okinawa, and two I grew up in South Bend, WA and knew the Bush family personally as well as his wife, Wanda’s family also. My mother worked as Bob’s bookkeeper at Bayview Lumber for 30 years. My sister baby sat for the Bush family often. That photograph is NOT Bob Bush. change it!