PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

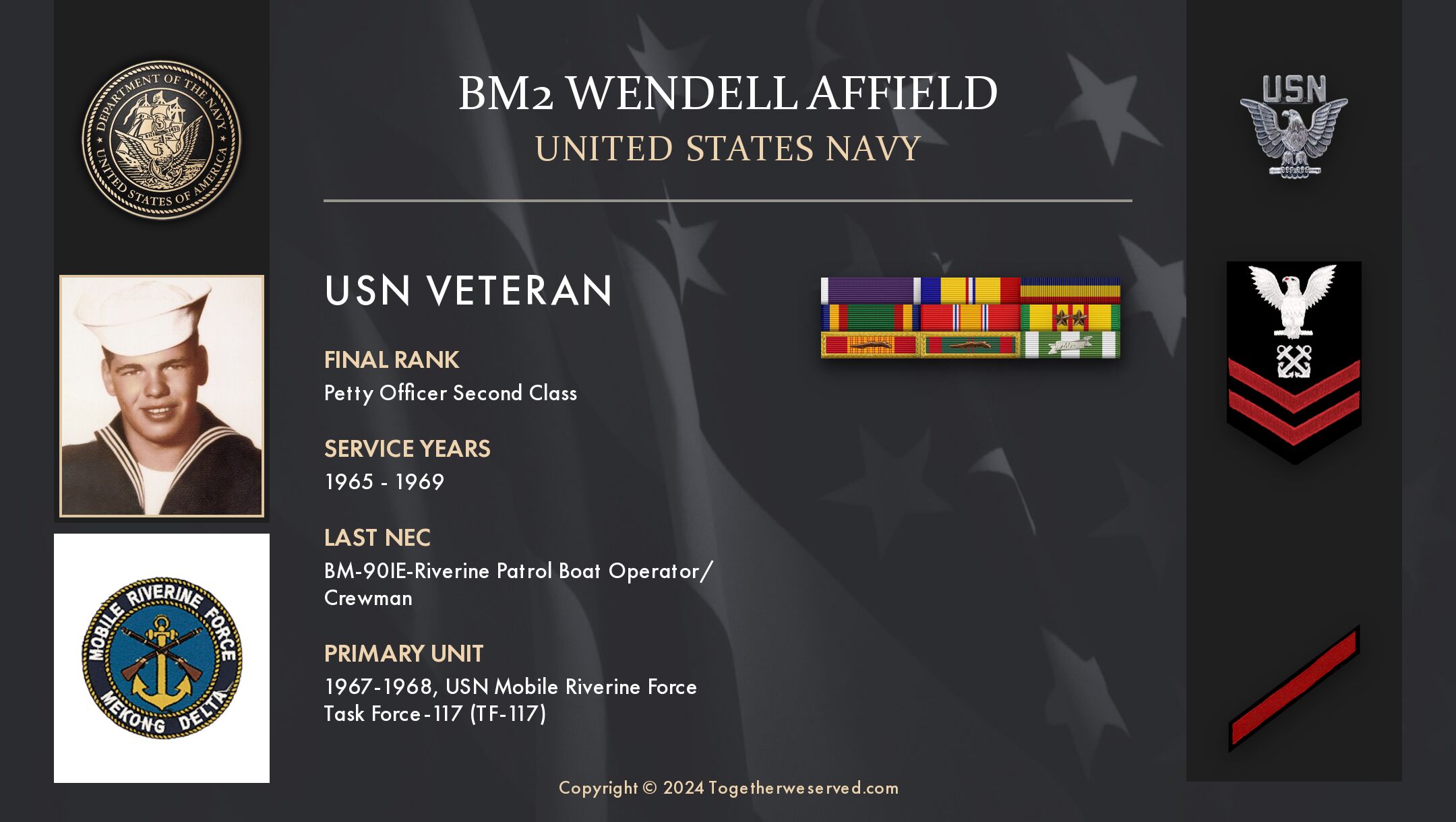

The following Reflections represents BM2 Wendell Affield’s legacy of his military service from 1965 to 1969. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Navy.

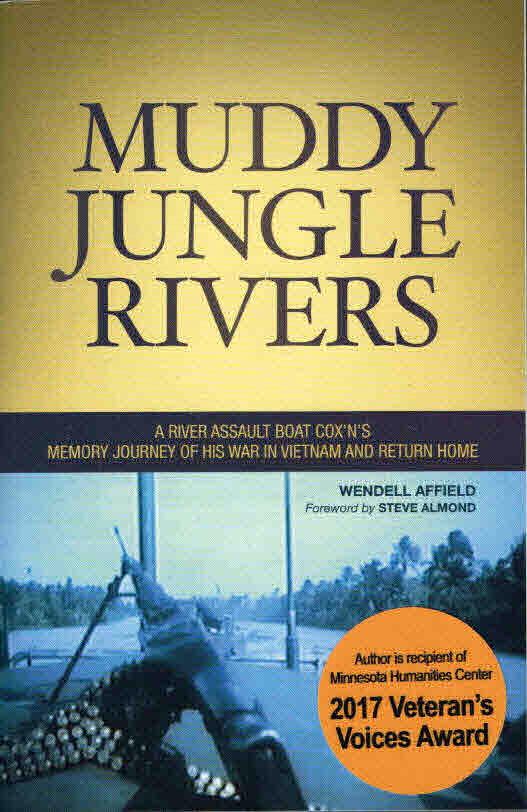

I enlisted soon after I turned 17. When I was 12, my mother was committed to a mental hospital. By sixteen, I had been through five foster homes. Spring 1964, I left, rode the rails, and lived in hobo camps in the northwest. An excerpt from my Vietnam War memoir “MUDDY JUNGLE RIVERS.”

That autumn, I returned to high school and stared out the windows? Had I lost all interest? Chinese dynasties, algebra equations, disassembled big blocks, and dissected frogs had no chance against the open spaces and freedom I’d discovered the past summer.

November of 1964, trapping season was in full swing, and I was disgusted with my predicament at home. On the first anniversary of President Kennedy’s death at school, there was a moment of silence followed by our history teacher reading Kennedy’s inaugural address. The challenge of his words resonated in my mind. “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.”

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution had been passed that August, authorizing President Johnson to send troops to Vietnam. The teacher spoke of communists overrunning Southeast Asia and moving down the archipelago to Australia just as the Japanese had tried twenty-five years earlier.

As I listened, I realized what I could do for my country. I could join the military and help stop the spread of communism. I turned seventeen that autumn, anxious to escape the farm, anxious to go to war before it was over? I walked nine blocks to the recruiter’s office, where I knocked on the Marine Corps recruiter’s door. Naturally, I would be a Marine. They built men and were the most heroic. Did I knock a second time? No answer.

I stepped down the hall and knocked on the Navy recruiter’s door.

“Enter,” barked a voice. I walked in, and the first-class radioman in dress blues greeted me.

“Do you know where the Marine recruiter is?”

“No. Are you thinking of enlisting?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Just between you and me, the Marine Corps sucks.”

And he had me. Because I was only seventeen, my mother signed permission for me to enlist. A week later, I was sworn in and on my way to naval boot camp in San Diego, California.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

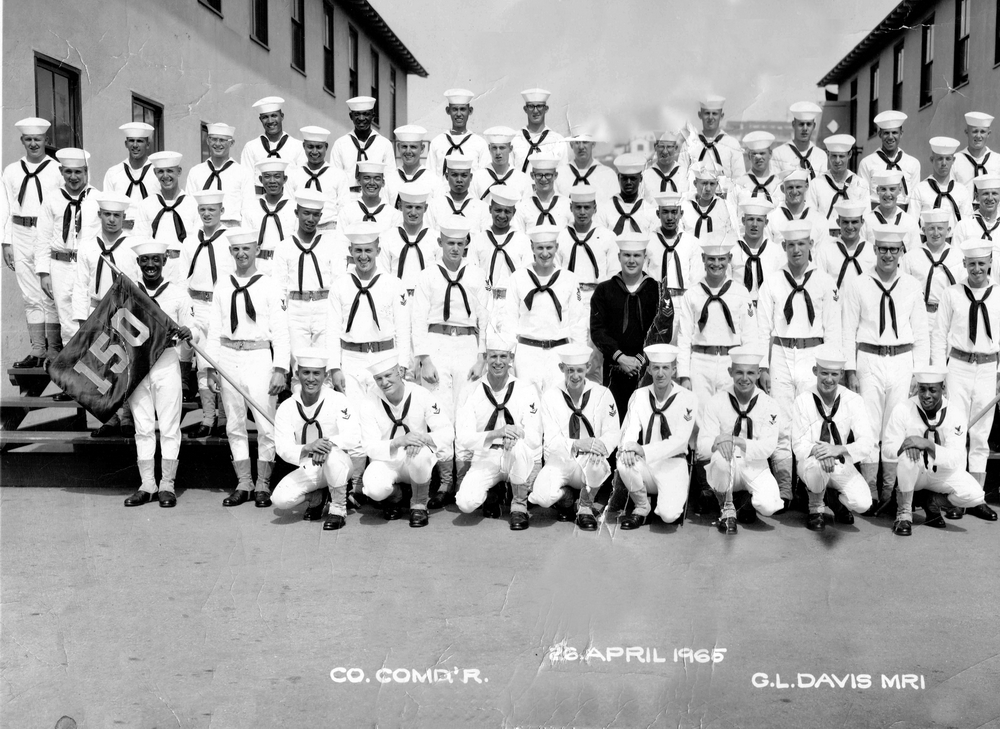

I was in from 1965-to 1969. Again, an excerpt from “MUDDY JUNGLE RIVERS.” Naval boot camp does not strive to break the recruit and instill that killer urge. Rather, it teaches tradition and discipline and focuses on selecting men for the hundreds of specialized duties necessary throughout the Fleet. I remember the batteries of tests and the boredom I felt as I glazed through them. Failing dismally, I was assigned to the deck division and went directly to a destroyer, USS Rogers (DD 876), after boot camp.

I enjoyed the wide variety of tasks and was soon singled out for training. A quote from an early performance evaluation, “A field is highly effective and reliable. Needs only limited supervision.” I was sent to Water Survival and Pilot Rescue school. As I recall, out of about thirty students from several ships, five of us passed the rigorous class where we spent 12-14 hours a day in the water.

Shortly after that, I was assigned to the ship’s landing force party. Marines trained us in the hills of Camp Pendleton, north of San Diego. It was a grand game with real guns and blank ammo. I remember how I basked in an old gunnery sergeant’s praise when I charged an ambush. A few nights later, dug in atop a marl knob, the Marines charged our position in a rainstorm. My M-1 rifle jammed, and the old sergeant stood over my foxhole, firing into the air. “You’re dead, asshole.” Then he walked away laughing. My gun unjammed; I glimpsed him in a flash of lightning and fired in his direction. The next day, sitting in a classroom as we listened to a critique of our defensive perimeter, the sergeant limped in. “I catch the bastard who shot me with a plug last night; I’ll have his ass.” We all laughed.

A few months later, the USS Rogers left on a WestPac cruise, an acronym for West Pacific, synonymous with Vietnam. We left San Diego in late January 1966 and returned in August.

I saw my first dead American while we patrolled the Gulf of Tonkin.

We were at General Quarters. We’d come close to shore searching for a downed pilot. I was dressed in a wetsuit, ready to drop over the side to help him. He had limped his shot-up F-4 Phantom out over the water before he’d ditched. The plane must have disintegrated on impact. As our ship eased through the debris field, the top of an open parachute was spotted about thirty yards off the port side. The phone talker relayed the captain’s order, “Swimmer over the side.” I was on the seaward side of the guardrail, and one leg hooked inboard. A geyser shot skyward twenty meters off the ship’s stern at that instant. Another artillery volley bracketed us. An explosion of spray off the port side drenched me. The ship lurched forward, and white foam churned from her screws. We jumped into the gun mount and returned fire at the enemy guns firing on us from behind sand dunes. That afternoon, we set a record with twenty-seven rounds per minute fired over the next seven minutes until we steamed out of range.

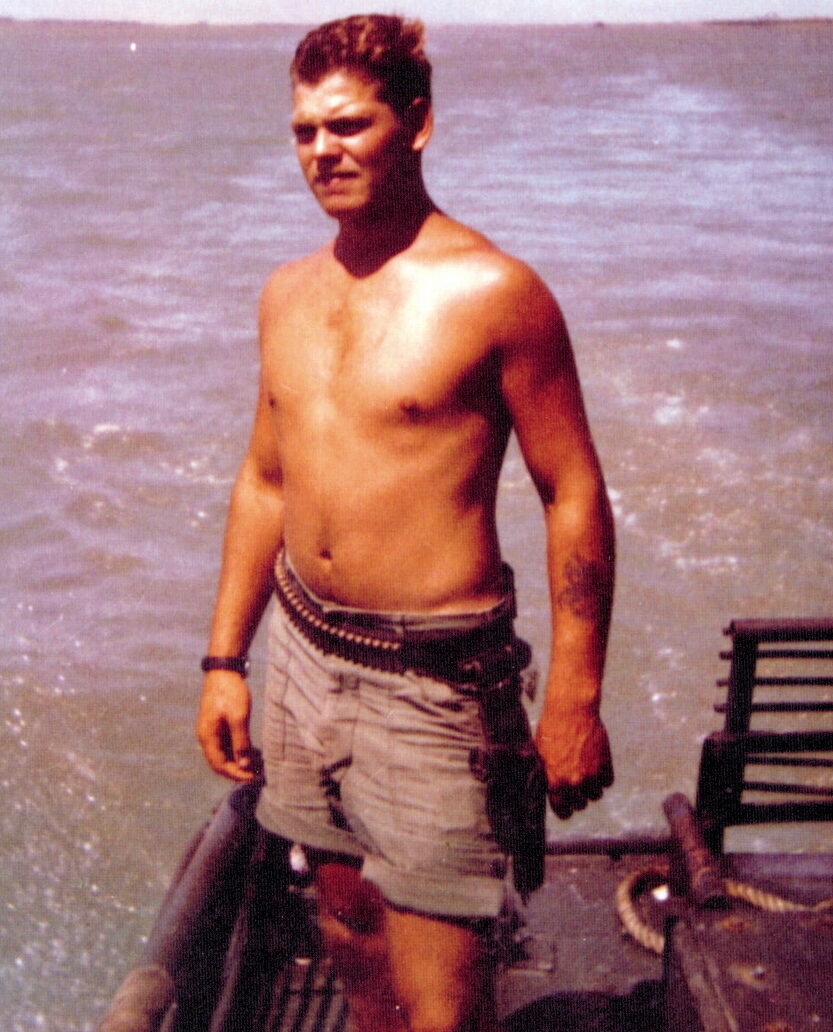

In 1968 I returned to Vietnam, cox’n of an armor troop carrier (ATC) with the Mobile Riverine Force. August 18, 1968, I was wounded in an ambush and medevaced to Great Lakes Naval Hospital. I met a girl, and that put an end to my military plans.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

Serving as cox’n on Armor Troop Carrier (ATC) 112-11 (commonly known as Tango boats) was undoubtedly the most significant and life-changing event for me. 1968 is often referred to as the “bloodiest year of the war,” and we saw our share. In the I Corps with the Marines, our squadron kept the Cua Viet River open for several months.

Then back to the Mekong Delta, countless small operations, one big one into the U Minh Forest.

Did you encounter any situation during your military service when you believed there was a possibility you might not survive? If so, please describe what happened and what was the outcome.

Several times. Incoming artillery from North Vietnam.

Mines in rivers–witnessing other boats sink–men KIA

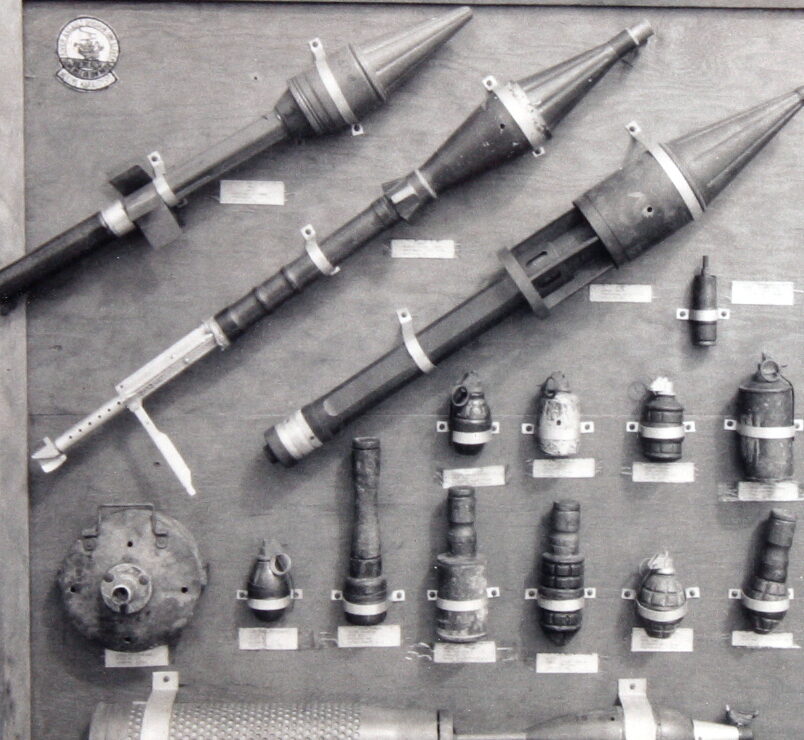

Ambushes–eventually my turn came on 18 August 1968 when I was wounded by four different rockets.

Rockets used by Viet Cong-NVA

B-40

RPG-7

B-50

75mm Recoiless Heat Round

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

My Fondest memories of men I served with on the USS Rogers DD 876 and on my Tango boat with our seven-man crew.

My least favorite transit barracks in Yokosuka, Japan. At the end of our 1966 WestPac deployment, we stopped in Yokosuka to off-load ammunition leftover from our last patrol in Tonkin Gulf. While on a work detail carrying 5’38 ammo, my appendix ruptured, and I was left behind in the base hospital.

After recuperating, I was sent to the transit barracks to await transportation back to the U.S.

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect back on to this day.

What has impacted me most, In the early 1990s, I was diagnosed with PTSD. Let me share a few excerpts from my memoir MUDDY JUNGLE RIVERS: I’m pulling a dead body from the river? “I took the hook then and snagged his rib, pushed down, and pulled him to me.

He was barefoot and shirtless but still wore jungle fatigue pants held on by a web belt. He was a Caucasian male, couldn’t really tell his age, about 180 lbs., brown hair. Birds or fish or water bugs had devoured his lips and eyes. I turned my face away when gas bubbled from his distended belly.

“Come on, Afe, what’s the hold-up. Get him on board.”

I took a deep breath, held it, and bent over the side with the stretcher. The west breeze and the river current kept him against the boat, and his outstretched fingers tapped the side. I tried to maneuver the stretcher beneath him, but one of his legs was hanging low, and I couldn’t reach down far enough to get past it. The stretcher was too long and unwieldy.

“Hurry, Afe, we’ve got to get away from this bank.”

“I can’t,” I sobbed as I gasped air in, then sprayed vomit out over the body. “I can’t.”

“Get him the fuck out of the water. Now.”

In desperation, I flung the stretcher back on board, then bent down, grabbed the body’s belt, and pulled. A stiff leg, the one that had been floating, rolled with him over the rail. I felt him slip back and threw my arms around his sticky waist, hugged him to me, and rolled onto the deck where I lay beneath him. I think I screamed. Nothing coherent. I was being smothered, his bare chest against my face, water oozing into my mouth from his rancid body. I slipped out from beneath him and stood, gasping dry heaves. My lungs rebelled, and I retched, unable to draw a breath. Something clung to the top of my head, hung down past my ear against my cheek. I wiped a hand across my face to push it off. Seaweed, I thought.

“How are you doing, Afe?” Buddha said, directing a red-beamed flashlight on the body. The light gleamed on the exposed bone that ran from elbow to hand. The mass sticking to my face was flesh. “Oh,” came out as I recoiled. My bare feet shot out from under me on the slick deck. The body’s chest cushioned my elbow and forced a gurgling sigh to bubble from his throat.

Decomposition and concussion grenades had weakened the body. The shard of flesh had the texture of raw lutefisk, and it slapped me across the mouth when I ripped it from my head.”

In another excerpt, we are receiving incoming artillery from North Vietnam. Shrapnel ripped through the screen and ricocheted off the corrugated tin like hail on a barn roof.

I was too far from the boat. Besides, they were already out in the river, and I’d have to pass the supply staging area to get to the river bank. The threat of friendly fire was a risk to be considered if I tried to race across the base. I stood in the sand at the foot of the beer hooch, watching flares drift overhead. Why were the Marines lighting the target up, I wondered. A round detonated not far from me, and I raced for the shallow crater. I recalled what an army guy had said back in the Delta. When you’re in a hole, it’s just bad luck if a round falls directly on you, kind of like lightning striking twice in the same place. I realized I was terribly drunk, and I was struck from above.

“Man, get your ass down. There’s room in here for us both.” It was a black guy from his voice, and he had jumped feet-first into the hole and hit me in the head with his boots. For the next two hours, we hugged the depression. I lay on my stomach, fingers locked onto fistfuls of sand as I tried to become one with the earth. Each time a round detonated, we’d bounce up then back down with the air pushed from our lungs and sand raining down. I realized I was holding my breath, waiting for the next round, the one that was sure to fall directly on me. Two rounds bracketed close, and I dug a hole for my arm that I could rest my forehead on. At times we screamed; not for help here was none.”

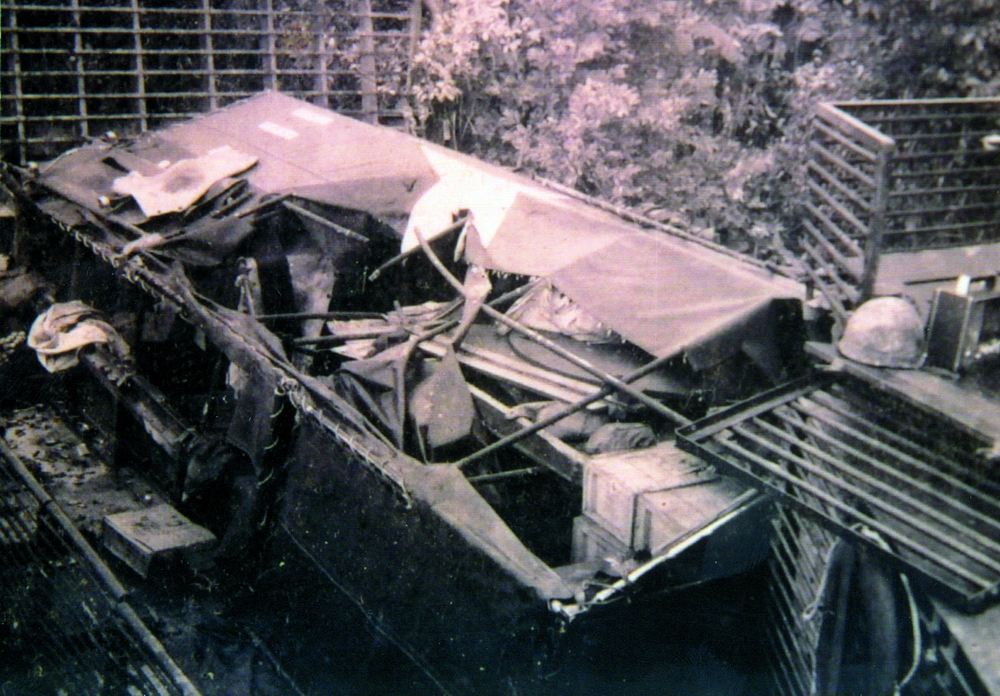

The day I was wounded—” An explosion on the starboard shield knocked me against the radio. Hot smoke clouded the compartment. Professor pulled himself to his feet then helped me up. I grabbed the helm and tasted blood as it dripped onto the instrument panel. My jaw ached. I tongued broken teeth and realized that my face had hit the bulkhead when I was blown back.

“Afe, turn the boat turn the boat. The current is swinging it downriver,” Buddha bellowed through the smoke and noise.

“Tango one-one, send damage report, over,” demanded the radio.

“Afe. Swing the boat. We’re dead in the water right in front of their rockets.”

I watched muzzle flashes through smoke rising on the riverbank as my hand reached instinctively to shift the starboard engine into reverse so the boat would swing back into the current. My fingers closed around the cool, sweat-polished brass shift lever, and a rocket penetrated the armor a few inches above my hand.

Seared flesh and burned hair smell filled the compartment; a stench like the white-hot docking iron we’d used to sever lambs’ tails in the spring. I heard high-pitched plaintive bleats. Lying on the deck, looking up through smoke and flames at the armor, I focused on the hole not there moments before.”

And there are many other memories.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

I have the standard Vietnam service ribbons from two deployments, including a Purple Heart and a Combat Action Ribbon. An event that brings me pride is my connection with some army troops that were on my boat the day of the ambush. The day I was wounded, we had a full platoon of troops on board, many of them wounded, at least one killed. At that time, I didn’t know any of the army troops. Forty years later, we connected at a Mobile Riverine Force Reunion.

Read this blog post titled “Ambush Survivors Reunited 45 Years Later: Memories from August 18, 1968.”

Each August, I post a memorial on my Facebook page to the five men who died on the operation and the eighty-two who were wounded. This past year, Larry Reid, one of the army troopers, commented, “(Wendell) That specially trained North Vietnamese heavy weapons unit tried their darnedest to kill everyone in our ATC. You did a hell of a job getting us out of the kill zone Wendell. I’m sure you saved my life, and I will never forget that. The months of May and August hold memories that haunt me every year. Vietnam changed us, but it didn’t destroy us. Hang in there, and let’s meet when this wave of the pandemic is over.”

The image attached to this question:

B-40 Rocket hit the port side, the .50 cal mount, and burned through, wounding all three gunners. One Rocket Hit under the mount and detonated on the Armor and didn’t penetrate the armor plate.

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

I think that successfully completing the pilot rescue/water survival school was significant when so many failed.

Some would say my Purple Heart is significant, but I often wonder why. Survivor guilt the shrinks say.

I was wounded on August 18, 1968, in an ambush while at the helm of an armored troop carrier heading north on Hai Muoi Tam Canal in the Mekong Delta. With a platoon from the 9th Infantry Division aboard, our Mobile Riverine Force boat was mid-column when hit with automatic weapons fire and seven rockets. One of the three rockets that struck the cox’n flat penetrated the 1-inch armor, wounding the navy radioman and myself. I was sprayed with shrapnel, my ears were damaged, and my eyes severely burned.

To be a member of the Mobile Riverine Force is special, but then, a crewman on the Rogers is too.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

Commander CD Clark, Captain of the USS Rogers DD 876, holds a special place in my memory. From the early days on the ship, I stood bridge watches, so I was in daily contact with the Captain. He saw something in a seventeen-year-old high school dropout and gave me encouragement and the opportunity to grow. After almost two years, I had earned my GED high school diploma, attended training schools, and advanced to E-4. I was sorry to see him leave the ship.

From the Rogers that I am in contact with: Chris Ogden, we visit occasionally; Terry Bendon; Tony Welch; Ron Stevenson. A few years ago, I spoke at Indiana University to the class that used my book. Chris, Ron, and I had a mini-reunion; sadly, Ron died in an auto accident shortly after.

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

From left to right: Larry Reid, Cleve Chick, David L. Cowley, Larry R. McCormick, Wendell Affield

(To put this blog post in context, please read the August 18 post.)

Reunions can be poignant, frightening, illuminating. My wife, Patti, and I attended the 2013 Mobile Riverine Force Association Reunion held in Indianapolis this past week. I was saddened to see how age and Agent Orange illnesses have ravaged our ranks. One of the founding members of the MRFA stoically told me, “The doctors give me about twelve months.”

But there were moments of disbelief, too. About a year ago, Larry Reid, Nashville, Tennessee, an army veteran who had been riding our boat when we were ambushed on August 18, 1968, discovered “Muddy jungle Rivers” on Amazon and purchased it. Over the past twelve months, we’ve been in touch. On the first day of the reunion, he introduced himself. We compared notes on how our lives have evolved over the past four decades. On the second day of the reunion, Larry came up to me and said, “I found three guys who were in the well deck on August 18.”

It was an intense experience.

Larry R. McCormick, Amarillo, Texas, looked at me, frowned, and shook his head. “I thought you were dead these past forty-five years.”

“Why would you think that?” I said

“Because of all the blood dripping down from your cox’n flat above me. And the boat kept running into things.”

“Each time rockets hit my armor plating, I kept getting knocked down,” I told him.

He asked an unusual question then?one I’ve never thought about. “How many times were you hit?” I have always considered the ambush one action?not multiple injuries. I thought back for a time and told him, “Four, I suppose.”

We all visited then and recalled that hot Sunday afternoon, and I thought again how each of us remembered differently, yet all held some memories. David L. Cowley, from “The Great State of Texas,” brought up what we all remembered most vividly. Blood splattered everywhere. Blood trickling across the welldeck deck. The heroism of already wounded men, cradling smoldering crates as they struggled across the slick deck to throw grenades and ammo overboard before it exploded.

I brought up the black army sergeant who had come up to man our abandoned .50 caliber machine gun. I told again how he had been severely maimed when a B-40 rocket burned through the armor, and he took a direct hit. Cleve Chick, Elkridge, Maryland, recalled that he was a career man who had recently joined the platoon. Most of the men didn’t know him. “Thomas,” Cleve said. “His last name was Thomas.”

Larry gave me a list of twenty-three army men who were on ATC 112-11 who received a Purple Heart for wounds received on August 18. Two names are missing: Hector Lugo-Mojica, who was Killed in Action, and the black sergeant named Thomas.

I wonder if Sergeant Thomas was the senior man on board ATC 112-11 on August 18. In the chaos of that day, I believe his act of heroism went unnoticed and unrecorded. I would very much like to identify the sergeant. If he did not survive his wounds, his family deserves to know of his actions. If he did survive and is still alive, I would very much like to meet him.

I am humbled that “Muddy Jungle Rivers” was the catalyst that brought us together.

Can you recount a particular incident from your service, which may or may not have been funny at the time, but still makes you laugh?

While on the Rogers, we were visiting Yokosuka, Japan. One evening in a bar, an engineman stood up to make a toast, chug-a-lugged a bottle of champagne, and it shot back out like Old Faithful.

A not humorous incident:

When our medevac plane landed at Glenview Naval Air Station north of Chicago, and antiwar protestors assaulted our convoy: from MUDDY JUNGLE RIVERS.” 29 August 1968

It was a bright autumn day. Cool, clear I was surprised not to smell burning leaves. We loaded onto gray navy buses for the ride north to the hospital. As our bus meandered across the base, I smelled fresh-mown grass along the boulevards where marigolds and pansies sparkled in the breeze. Sailors, working slowly, picked weeds from flower patches tending lawns seemed somehow surreal. Nearing the gate, we stared at men in crisp uniforms saluting each other, shiny cars passing through, and it was a world we’d forgotten. Then we were beyond the security of the base.

A large group of people stood on the sides of the street holding signs welcoming us home.

Eggs and tomatoes splattered the windshield, and Wipers smeared a pasty reddish-yellow crescent.

The bus slowed, and a ripple of noise washed over us. Anti-war protesters blocked the street, in front and behind the bus. We couldn’t move. The mob surrounded us. They screamed and waved signs. They attacked with rotten fruit, tomatoes, bricks. As they gained courage, they began hitting the bus windows with clubs, fists, and protest signs; screaming obscenities and lies. The protester’s shouts blended to an indistinguishable blur in my ringing ears.

Beyond the stretcher, beyond the garbage-splattered window, a girl’s hate-filled face twisted as her mouth stretched wide, screaming at us. I caught snatches. “fucking killers rot in hell.”

Bricks thudded against the bus. It edged forward when the mob tried to force the doors open. I was at a loss when I looked into the raging faces of the young people banging fists against the windows. The confrontation was over as abruptly as it had begun. Eggs and tomatoes splayed back windows. I watched through splattered yokes as protesters shrank in the distance.

What profession did you follow after your military service and what are you doing now? if you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

I worked 30 years in the food industry and retired in 2001. I attended our local college Bemidji State University (Minnesota), to learn the writing craft because I knew I had stories to tell, and if I didn’t get them on paper, they would die with me. In 2012 my memoir, “MUDDY JUNGLE RIVERS,” was published. This year, 2022, is the tenth anniversary. Since then,

I have written three more books. Read about all of them.

What military associations are you a member of, if any? what specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

Life member of VVA and DAV. Member of American Legion. Not really active.

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

After retirement, when I attended college, I discovered an interest in psychology. (All of my books deal with life traumas and my mother’s mental illness). While in Vietnam, I sympathized with the plight of the farmers and fishermen, the poverty, and no hope of a future. Today I work with the homeless and at our local Food Shelf.

Several years ago, one of our VA Clinic doctors asked me if I would consider facilitating an expressive writing group for veterans who struggle with trauma memories. Six years later, the program is alive and well.

Today I facilitate a Veterans Writer Group and do Writing Workshops.

My 4th book was recently published. From Amazon: BARBARA, Uncharted Course Through Borderline Personality Disorder is a riches-to-rags tale about an extraordinarily talented, troubled young woman. After Barbara died in 2010, the author Wendell Affield discovered thousands of documents locked in a rodent-infested chickenhouse. Having spent his childhood living with his mother’s mental illness, Affield studies the contents in an effort to understand his mother’s life and search for clues to his biological father.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Navy?

The Navy gave this seventeen-year-old kid a sense of direction and hope. I believe that in today’s military there is so much opportunity to grow life skills while serving our country.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with.

As with the military organizations I belong to, I have not been very active with this group either maybe I will grow into it.

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

0 Comments