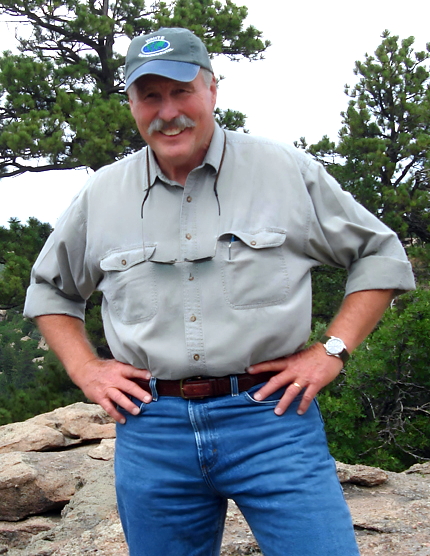

PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

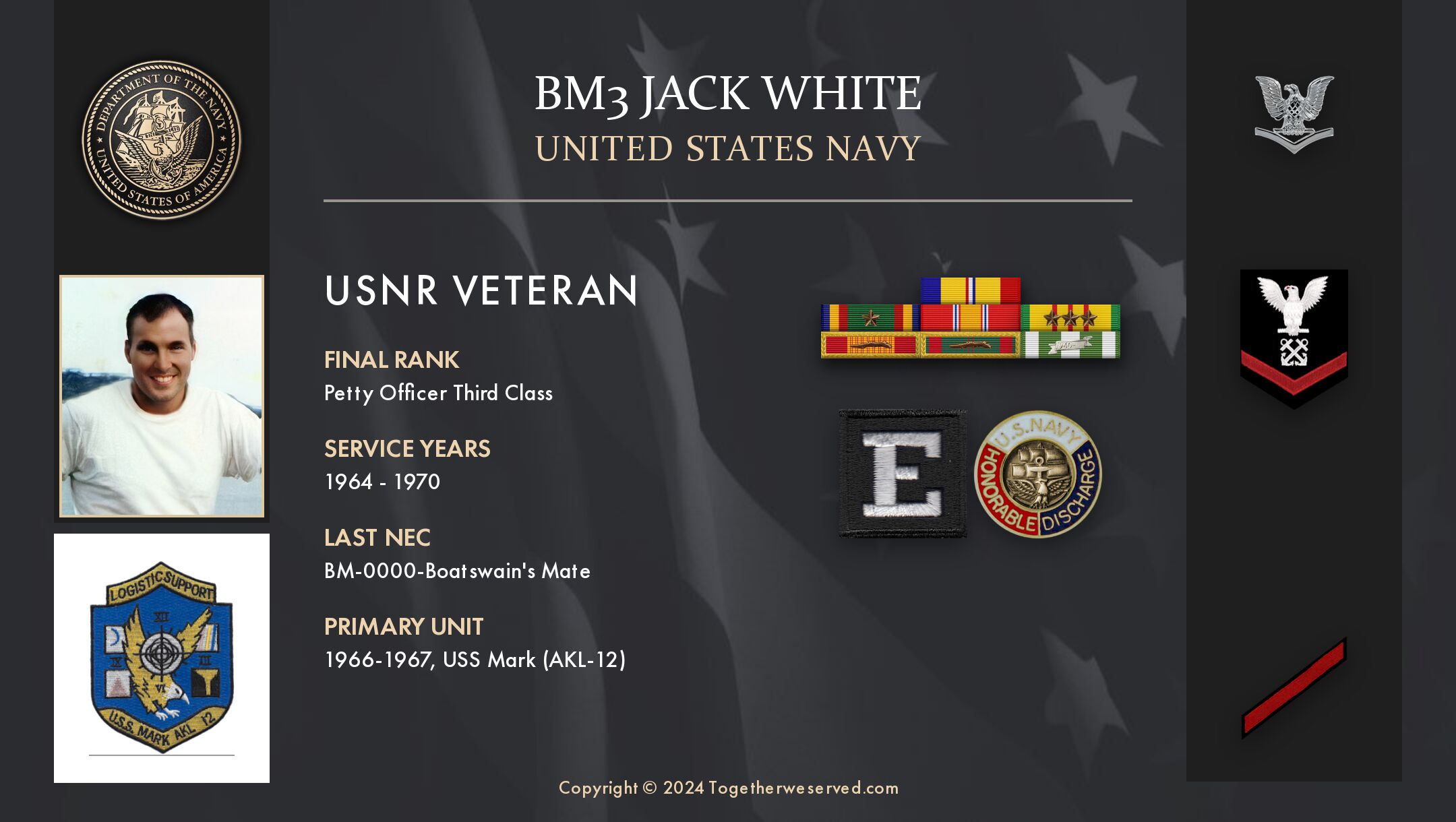

The following Reflections represents BM3 Jack White’s legacy of his military service from 1964 to 1970. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Navy.

Several factors influenced my decision to join the Navy in 1964. First, in 1960, my senior year at Canoga Park High School, I received a congressional appointment — fundamentally, a football scholarship — to the U.S. Naval Academy with the provision that I enroll at Pierce Community College in Woodland Hills, California. Pierce was one of the community colleges designated by the Naval Academy and their football coach, Wayne Hardin, as having an athletic training program capable of transitioning appointees to a higher level of experience and expertise before our entrance to the Academy. Well, that worked out fine for a few months; I had passed the Navy physical and had a good football season, but then my best childhood friend and I decided to join the Tri Chi (XXX) fraternity at Pierce College. Then, fraternity life provided an entirely new and exciting social avenue to discover; however, my grades suffered due to the newly introduced fun factor in my life.

Consequently, I failed to maintain the required grade point average and thus lost my appointment to the Academy. I considered the loss inconsequential at the time, as I had the time of my young life. I felt bad for my parents, who were pretty proud of the appointment and never really got over it. As for me, I suppose I will continue to replay the pros and cons of that decision through the years.

So, fast forward through about four years of joyful fraternity life — supported by my employment as a rocket engine test mechanic — to the second factor that influenced my decision to join the Navy. My longevity as a “student” at Pierce College finally ended in 1964, when I received notice that my student deferment from the draft was cut short by — you guessed it — a draft notice stating that I must report for a physical for my induction into the US Army. Well, I didn’t want to join the Army . . . I wanted to join the Navy. So, shortly after passing the Army physical, I sought out Navy programs that might accommodate my desire to continue my college education in a serious way following active duty.

The USNR then had a 6-year program: 2 years active duty, two years active reserve training drills, and two years inactive reserve duty (no drills). That sounded perfect, so I enlisted. The recruiter suggested I consider doing my active reserve first, as that would allow me to advance from E-1 to E-3 while on active reserve, provided that I passed all of the tests. I started my active reserve training by going to boot camp at San Diego Recruit Training Depot at Liberty Station in 1964. Then, I passed all of the tests promoting me to E-3 when I received my orders to report for active duty in April 1966.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

In April 1966, I received orders to report for active duty aboard the USS Mark (AKL-12), a light cargo ship home-based at Subic Bay in The Philippines. As it turned out, I was one of about eight new crewmen who reported aboard at that time. Most of us (including me) were assigned to the deck force, but a couple of us had been assigned to the engine room below deck.

We soon found out that the Mark was attached to Naval Support Activity, Subic Bay. The ship’s primary responsibility was to deliver various materials across the South China Sea to various coastal-patrol Navy bases along coastal Vietnam (Danang, Qui Nhon, Nha Trang, Cam Ranh Bay, Vung Tau, and An Thoi) as a part of the Market Time logistical support program. The primary objective of Market Time was to interdict and limit the movement of the seaborne infiltration of supplies and munitions being supplied by the North Vietnamese to the Viet Cong via junks, sampans, and other small craft along the 1,200-mile South Vietnamese coast.

In June 1966, the Mark was reassigned from NSA Subic Bay to NSA Saigon, when we began to provide logistical support for the Navy’s River Patrol Force, which was performing interdiction and patrol activities in the Mekong Delta under the Game Warden operation. The Mark was a small (180 ft long x 33 feet wide) single-hold cargo ship with a very shallow (10-foot) draft, making it an excellent choice to navigate the shallow riverine waterways in the Mekong Delta. So, we were now officially a part of the Brown Water Navy.

Unloading and offloading cargo was the primary function of the ship, using a single swinging boom.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

The USS Mark played an integral role in successfully implementing two important military operations during the Vietnam War: Operation Market Time (coastal surveillance and interdiction) and Operation Game Warden (aimed at establishing firm military control of Mekong Delta waterways). A series of strategically located naval bases were established at key coastal port areas and throughout the Mekong Delta under each operation, respectively. All of these bases required logistical support to ensure the continued functionality and success of the military operations carried on at each naval base.

The Mark was responsible for the timely delivery of cargo of all sorts to coastal and riverine bases, all of which were in the war zone. In between each naval base, we were at General Quarters (GQ), during which we manned all gun mounts and remained prepared for Viet Cong ambushes and sniper fire, both of which we experienced on certain anxious occasions. Most of the time, there were no prolonged firefights, but on two occasions, we had to fight our way out of ambushes. The firefight for which the ship and crew were subsequently awarded the Navy’s Combat Action Ribbon occurred on the Long Tau River during our return to Saigon on 15 February 1967. About 20 minutes after going to GQ and entering the Long Tau River from Vung Tau Harbor, we witnessed two minesweepers (one was MSB-51) and four PBR escorts receiving heavy automatic weapon fire from both banks of the river. We commenced with opening fire at both river banks with all of the ship’s armament while moving upriver toward Saigon for a period of 20+ minutes until all ships and boats were safely away from the ambush.

In an earlier memorable firefight (16 January 1967), we were ambushed by sniper fire on the Cau Tieu River about two hours from the My Tho naval base. We returned fire, but fortunately, we were saved from an extensive firefight by rocket fire from US Army L-19 aircraft.

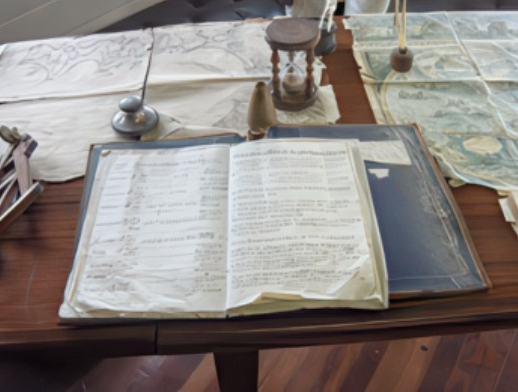

It goes without saying that combat leaves a lasting impression on all who participate. Personally, I found it initially challenging to remain focused on my role as shell-feeder in manning the 81MM mortar at my GQ station amidst the confusion following an ambush, which was usually a surprise situation. However, the training kicks in, and it then becomes easier to accomplish what needs to be done. I only had three choices regarding which shell to feed — high-explosive, (HE) white phosphorus (WP), and incendiary — and we mostly used HE rounds. For example, according to information in the Mark’s Deck Log Book from February 1967, we fired 30 HE rounds, and one WP round during the firefight on the Long Tau River described above.

In reflecting on my combat experiences, I can honestly say that they were always a bit scary, but they allowed me to gain some good insight into who I was and would be as a person and team player. Those experiences tended to build a sense of camaraderie, dependence, and accomplishment among members of the crew. Additionally, as with the undertaking of normal shipboard responsibilities, I learned who could be counted on to carry out their roles responsibly. It taught me how to work with and direct (in my role as Leading Seaman and Hatch Captain) the actions of people hailing from different parts of the US. That experience became quite useful in later life when my career as an environmental consultant required me to interact with clients and manage multidisciplinary teams of professionals to complete large projects successfully, nationally and internationally. I consider my Navy experience as being directly tied to my ability to complete such projects.

Did you encounter any situation during your military service when you believed there was a possibility you might not survive? If so, please describe what happened and what was the outcome.

Actually, only one occasion during my military service made me think survival might not be the outcome. It was during one of our crossings of the South China Sea, from Subic Bay in the Philippines to Vietnam. For the most part, the South China Sea is beautiful and can be as calm as an inland pond. In that regard, on one crossing, I actually had the opportunity to witness sea turtles mating in glass-like waters a half mile away while I was standing watch on the flying bridge. It was a beautiful ritual to witness through my binoculars.

However, on another quite the opposite occasion, we encountered the deadly conditions of a typhoon. It was unlike anything I had ever experienced in my life (to this day). I can’t recall how much forewarning we had, but I know that we had to securely lash down our deck cargo together with everything else that stood a chance of shifting from its normal position, including securing the cradle for our single swinging cargo boom. In addition, we had to install a series of lifelines from all hatches leading from below decks to the main deck and conning tower area to the bridge to provide officers and crew with an added level of safety when using the ladders to gain access to the helm to steer the ship or stand watch.

Despite all of the preparations, the typhoon hit us with such incredible force that the Mark was severely challenged to make way through the high winds and 50-foot waves primarily due to the ship’s relatively flat bottom and shallow (10-foot) draft. It felt like we were riding on a cork, trying to make our way through those waters. I can remember taking my turn at the helm, being directed by the quartermaster to turn the helm to a position where the ship would hit each of the oncoming, incessant waves at an angle to avoid being capsized. I’ll never ever forget the relentless sight of those huge waves advancing toward the ship, wave after wave after wave. The typhoon lasted through the night, and the most anyone could handle on watch, especially at the helm, was two hours (half of the standard four-hour watch). After our turns on watch, we would retreat below deck to the galley for coffee and crackers or to our racks to sleep. I remember that about all anyone could keep down was coffee and Saltine crackers. Virtually everyone was seasick.

Was the end near? It sure felt like it. I really was uncertain whether or not the ship and its crew could successfully navigate through this treacherous typhoon . . . but we did. It took several days to recover from this unforgettably harrowing, life-threatening experience, and I still harken back to those anxious moments during which I had wondered if this typhoon would be the end of the ship and its crew. I credit the experience of the Captain (LT Frank Sanderlin) and Quartermaster (QM1 Charles Law), in particular, in taking control and wisely guiding us through this unforgettable, life-threatening situation.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

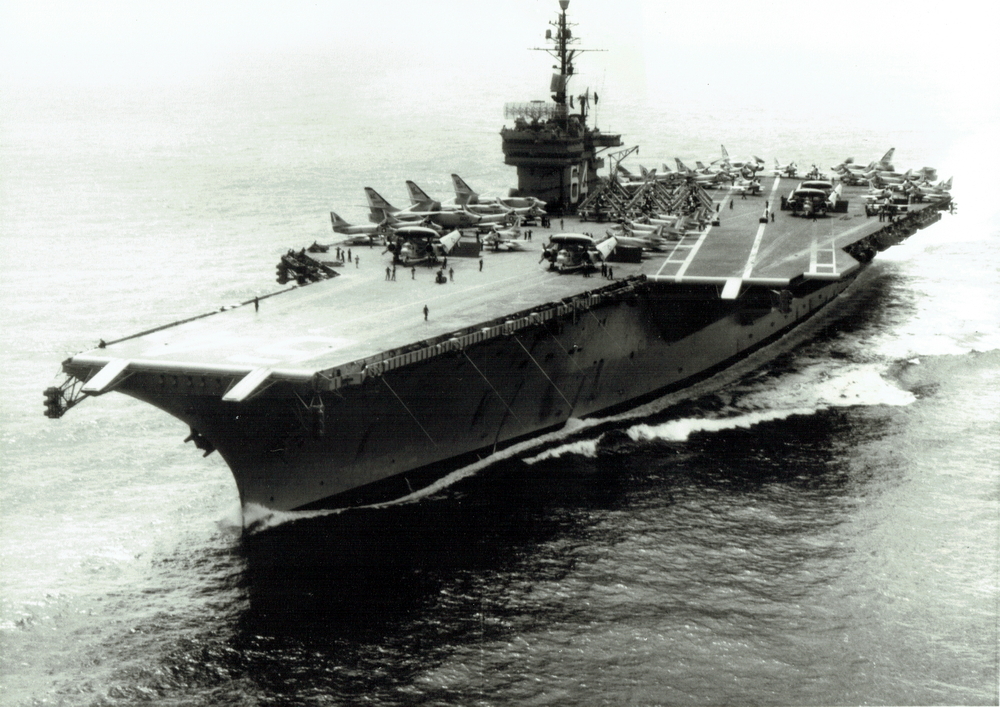

During my two years of active duty, I only had two duty stations: aboard the USS Mark (AKL-12) from 7 April 1966 to 1 October 1967 and the USS Constellation (CVA-64) from 1 October 1967 to 8 April 1968. In comparing my experiences between these two assignments, my going-away favorite was my service aboard the USS Mark, for the reasons explained below.

First — fairly or unfairly — I have to say that the two years of active reserve duty (i.e., monthly meetings, plus boot camp) was not adequate preparation for my experience aboard the USS Mark. I reported for duty in Subic Bay, Philippines, thinking I was ready to be a “sailor.” However, I was not nearly as ready as I had thought. What I found from the very beginning was that I had entered another world. New rules, new expectations, totally new relationships . . . in fact, a whole new environment. Atop those first impressions was the reality that the Mark’s mission would take us to Vietnam. A war zone! Talk about an eye-opener!

Notwithstanding, I honestly believe that I was so very lucky to have been assigned for duty aboard the Mark. The officers (including a “mustang” lieutenant as the commanding officer) and a senior crew with plenty of Navy years under their belts turned out to be exactly the individuals needed to convert a civilian into a sailor. They were of the “old salt” school and, for the most part, had the patience, caring, skills, and guidance to transfer their essential knowledge to me and the others I walked up the gangplank with in April 1966.

That said, under the guidance of some extremely experienced and skillful First-and Second Class Boatswain’s Mates, Gunners Mates. Quartermasters who had adapted to the needs and mission of the Mark, we were able to learn what was needed from us as a deck force looking to function within this new environment, wherever the ship’s orders might lead us. At the time we reported for duty, I don’t believe that any of the officers or enlisted men aboard the Mark could have foreseen that (in June 1966) the ship would be headed for full-time riverine duty in the Mekong Delta as a part of what came to be called the “Brown Water Navy” under the Game Warden Operation, which was established to control the use of the many rivers in the expansive delta area.

Our particular mission was to provide ordnance, ammunition, spare parts, fuel, food, water, and other supplies from Naval Support Activity Saigon in support of strategic operations at far-flung US Navy installations throughout the delta. In addition, the Mark was also responsible for sounding the depths of several rivers to verify/update earlier French surveys from the 1950s for the purpose of supporting decisions to establish new base locations or confirm the wisdom of designating certain previously uncharted rivers as suitable for navigation in support of the Game Warden Operation. More about that later.

Given the Mark’s mission and the welcome reception my new shipmates and I received reporting aboard the Mark, together with our shared experiences in the war zone, I really can’t imagine a better memory for this period in my Navy career.

On the other hand, I had negative experiences aboard the USS Constellation (CVA-64) that were heavily influenced by my time in the Brown Water Navy aboard the Mark. Mainly, as a Boatswain’s Mate, I was obligated to stand the deck watches aboard the USS Constellation, which, I discovered, was quite a bit more formal than a similar obligation aboard the USS Mark. Specifically, it involved using my Boatswain’s whistle to pipe aboard high-ranking visitors — a situation I never faced in the less-formal Brown Water Navy. I had learned to use my Boatswain’s whistle to pass the BM-3 test, but then I never used it during the course of normal duty aboard the Mark. It was actually quite an embarrassing realization, but fortunately, one of my BM-3 mates aboard the Constellation was willing to stand my quarterdeck watches for $5. Thanks to him, I got through my time aboard the Constellation without an issue. Needless to say, I was extremely glad to learn that my time aboard the Constellation was cut short by about three months due to having received (for some unstated reason) an “early out” in January 1968; my normal active duty release date was to have been 8 April 1968.

So, I had an opportunity to experience two “different” navies: the Brown Water Navy aboard the Mark and the Blue Water Navy aboard the Constellation. With no offense meant toward the Constellation or anyone who served aboard her — she was a very fine, brave, and proud ship — I must say that I much preferred my time aboard the Mark. However, in September 2003, I attended the decommissioning ceremony of the Constellation at North Island Naval Air Station in San Diego with my next-door neighbor CAPT (Ret.) Walt Fraser (dec.), who had also served aboard the Connie and thought quite highly of her.

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect back on to this day.

One of the most indelible experiences in my Navy service history was when we surveyed the Bassac River in the Mekong Delta.

Because of her shallow (10-foot draft) profile, the USS Mark was uniquely responsible for several surveys of militarily critical riverine waterways in the Mekong Delta, including the Dinh River, Dong Nia River, and the Bassac River. These surveys concentrated on verifying the data recorded on charts prepared by the French when France was in control of South Vietnam in the 1950s. In July 1966, I was an integral part of demonstrating that the Bassac River was navigable from Can Tho to the South China Sea, a distance of 47 miles. Until that point in time, the reach of the Bassac River had not been navigated by commercial ship traffic since 1951. A combination of Viet Cong harassment and long-lost navigational aids had prevented anything larger than Navy patrol craft from making the trip. Of primary importance to NAVSUPPACT Saigon and the mission of the USS Mark was the fact that being able to sail from Can Tho (the last riverine Naval base stop in our responsibility to deliver supplies from Saigon to far-flung PBR bases) would significantly reduce the travel time required to do so — if we had dependable access to the South China Sea.

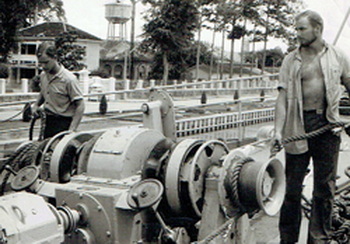

So, on 23 July 1966 (at General Quarters), with a French river pilot aboard, the military escort of a Vietnamese LSIL (HQ 331), a US Army L-19 to provide spotter cover, and a helicopter fire team standing by at Soc Trang, we undertook the 47-mile leadline sounding of the Bassac River. As a right-handed thrower, I was responsible for soundings off the starboard bow, and left-handed seaman James Tylman took the sounding of the port bow. We found that the shallowest depth recorded was 16 feet. As a result of our 5-hour plus effort, it was determined that passage on that important reach of the Bassac River was indeed possible with prudent seamanship and safe navigational practices. Hence, it was determined, for instance, that LSTs could, at high tide, successfully make river-to-sea passage through that reach of the Bassac River without a pilot. Among other benefits, this river-depth information would allow the Mark to navigate the Bassac directly to the coast in returning to Saigon, instead of having to retrace our two-day 160-mile route back up the Bassac and out the Mekong River in order to return to Saigon for the next load of cargo.

However, what fails to be recorded in the Ship’s Log is the unfortunate fact that we wound up missing high tide and consequently ran aground at the mouth of the Bassac River. That was an exasperating time, as we had to set up a perimeter on the sand bars surrounding our ship, preparing for an attack from the Viet Cong. We were like a beached whale and an easy target, as our list was such that we were unable to properly train our 50-caliber machine guns or our 81mm mortar on the shore area (or anywhere else, for that matter). Small arms were our only defense. Luckily, no attack came. As the incoming tide continued to right the ship, we saw the occupants of many small Vietnamese fishing boats staring at us while they made their way to check on their fish traps farther out in the delta. Once afloat, we continued our voyage to drop off cargo at An Thoi, located on Phu Quoc Island in the Bay of Thailand. All in all, quite a memorable event.

Another memorable experience occurred during my final three months aboard the USS Mark, which were spent in Japan. Built in 1946, the Mark was beginning to show her years, especially as it related to the dependability of the ship’s steerage and the need for a serious overhaul of her engines. In addition, the ship had to be refitted with an added layer of steel around the flying bridge and wheelhouse to provide added protection from recoilless rifle fire and other weaponry. Accordingly, Mark received orders to sail to Yokosuka Naval Shipyard for repairs and refitting in a dry dock. When we arrived in Yokosuka, we were told that there were no available dry-docking facilities at the Yokosuka Naval Shipyard, and orders had been cut to have the work done at an adjacent civilian dry-dock facility in nearby Uraga, Japan.

Well, that turned out to be a really good experience for the Mark’s officers and crew, as we were housed in the comfort of large beds and had daily access to a large Japanese bathhouse. Meals improved, and we all felt as though we had gone on R & R. Certainly, we had to stand daily fire, security, and quarterdeck watches when we each had the duty, but this new phase in our lives aboard the Mark bore no resemblance to our previous lives in Vietnam. When we were free of duty assignments, we could hop aboard the train and act like tourists in seeing parts of Japan’s beautiful countryside and cultural features. There were trips to Yokosuka, Tokyo, and Kyoto, and even treks to the top of Mount Fuji. It didn’t take long at all to adapt to this new sense of life in the Navy.

1 October 1967 marked my last day aboard the Mark, and I had to say goodbye to my shipmates and transfer over to the transient barracks at U.S. Naval Base Yokosuka to await the arrival of the USS Constellation, my next duty station. According to her deck log, the Mark departed Yokosuka on 9 October to return to Vietnam and arrived at Vung Tau, Vietnam, on 27 October, via stops in Okinawa, Japan, and Subic Bay, Philippines.

While in the Yokosuka transient barracks, I had several temporary active duty (TAD) assignments at U.S. Naval Base Yokosuka. On 20 November, while assisting in the mooring of a ship to berth, I had an attack of cellulitis. I went to the base dispensary and was sent to the base Naval Hospital, where I received treatment. I was released from the hospital back to the transient barracks on 1 December to await travel orders. I finally joined the crew of the Constellation in San Diego, her home port, by 14 December 1967. A little more than a month later, I was honorably discharged in San Diego from active duty on 5 January 1968.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

In thinking back, I am equally proud of two achievements, both of which occurred aboard the USS Mark. First, I was extremely proud to have been selected by CWO Boatswain’s Mate P. Mahoney as Mark’s Leading Seaman. At the time, that designation meant that I was thought to be the best Seaman among all of my deck-force peers, E-3 and below. And it resulted in my being considered for increased responsibility as well as being recognized as one who could advance in rank to Petty Officer.

The other achievement came about after I was designated as Lead Seaman. As Leading Seaman, I had the opportunity to become the Hatch Captain, working under the direct supervision of Petty Officer (BM-2 and BM-1) Boatswain’s Mates. The Hatch Captain was the person responsible for loading and offloading cargo in the ship’s hold, which was directly related to the accomplishment of the ship’s main mission: the delivery of cargo to remote riverine naval bases in the Mekong Delta and along the coast of Vietnam. Loading and offloading was accomplished using a series of hand signals by the Hatch Captain designed to control the direction and speed at that any given piece of cargo was being loaded or unloaded. During loading ops, the role of Hatch Captain also required a sense of how best to configure the load in the hold in consideration of the size, weight, and fragility of any given hoisted piece of cargo, as well as the space available in the cargo hold and the destination for each piece. It was always a welcome challenge, and I can honestly say that I definitely relied on the lessons I learned as a boy from my father (a Marine Corps veteran), as he demonstrated his uncanny skill in carefully and efficiently loading our car’s trunk with all of the “stuff” we needed to take on our biennial driving trips from California to Nebraska to visit my mother’s relatives. Dad was a packing and stowing wizard, and I was fortunate to have had that early example to rely on in my role as Hatch Captain.

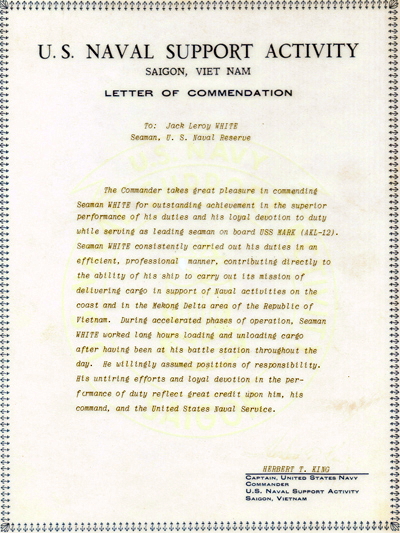

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

When I mustered out of active duty in the Navy in 1968, my DD-214 showed my award of the three basic Vietnam service medals: the National Defense Medal, the Vietnam Campaign Medal, and the Vietnam Service Medal.

That was fine for that point in time, as I was transfixed on completing my college education and finding a suitable civilian career. It wasn’t until I learned about and became a member of the Vietnam Unit Memorial Monument Fund (VUMMF) in Coronado, California, in 2004 in speaking with other Navy veterans that I had likely been awarded other medals and ribbons. Through Internet research, I learned I earned several other awards. Actually, it took several years to identify these awards and then successfully amend my DD-214 (via the DD-215 process) to officially acknowledge my receipt of the Navy Unit Commendation and the Combat Action ribbons, which now appear on my DD-215. And there were three other unit-based medals issued by the Vietnamese government for the service of the USS Mark (AKL-12) in Vietnam that were also awarded, but those foreign-government awards are not reflected on either a DD-214 or a DD-215. All five of these medals/ribbons were awarded after my discharge from active duty in January 1968.

I raise this DD-form issue as an advisory to all readers of these words to alert them to the fact that one needs to be aware of two important facts: (1) unfortunately, the Department of Defense does not automatically update form DD-214 to reflect awards earned after separation from active duty; and (2) as a consequence, it falls on each veteran to do their own research concerning unit-based awards earned after their period of active duty . . . and that is not an easy task.

That said, I must say that the most meaningful award to me is a personal (undated) Letter of Commendation I received from the Commander of U.S. Naval Support Activity, Saigon, Vietnam, toward the end of 1966. or the first part of 1967. It was the most meaningful because I was one of only four or five individuals singled out for this award. Moreover, it was presented to each of us in an assembly of the ship’s crew aboard the USS Mark. It was all the more special as we all wore our dress-white uniforms, a rare occasion in the more-casual Brown Water Navy.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

I can honestly say that virtually everyone in the 40-man crew I had the privilege to serve/interact/work with aboard the USS Mark (AKL-12) made a lasting impact on my view of and attitude toward working as a part of an interdependent team. As with most naval ship crews, individual crew members hailed from hometowns throughout the US. As such, each had interesting cultural traits and mannerisms, harkening back to the places they were from. I learned quite a bit about people in general from those interactions. I benefitted from the knowledge gained from those experiences later in life when I found myself dealing with people throughout the US while managing large multidisciplinary projects as an environmental consultant.

In the Navy and my post-Navy career, I appreciated the traits of caring, dependability, initiative, extra effort, a willingness to learn, and pride in one’s work as positive characteristics of individuals I felt were good shipmates and colleagues. That all began in the Navy. My time in the Navy also taught me that most everyone has something to contribute at some level . . . it’s just a matter of determining who can do (or learn to do) what and at what level. Whether it was sweeping the decks, chipping paint, painting, handling lines, tying knots, or battening down the hatches, it all had to be done and done right.

If I had to identify a particular shipmate who stood out in terms of having a lasting impact, I’d have to point to BM-2 Smiley as being the one person I learned the most from. He was our immediate supervisor and a very talented Boatswain’s Mate. I was thankful that he had a penchant for passing on his knowledge of seamanship to those who wanted to learn, and he didn’t mind answering questions.

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

I didn’t join the Navy with any friends or family relations. However, when a group of 8 or 9 new recruits gathered at the transient barracks in Subic Bay, Philippines, in April 1966 to await several days for the arrival of the USS Mark (AKL-12), I took an instant liking to Ken Renolds, one of the other members of that group. Ken was a surfer who lived in Sylmar, California, a town at the eastern end of the San Fernando Valley, where I grew up. I hadn’t known him before, but we became good friends aboard the Mark. After a while, Ken became a quartermaster striker, and I was a boatswain’s mate striker, but we kept in touch aboard the ship and went on shore leave together, along with other shipmates.

Unfortunately, I lost track of Ken once I mustered out of the Navy in January 1968. Still, I had a serendipitous meeting with him and his son one day in about 1995 or so in the parking lot of a hardware store in Calabasas, California. Ken was then a lieutenant in the Los Angeles Police Department, and during part of our “catching up” discussion, I learned that he had served a second tour of duty in Vietnam as a sniper. I would never have guessed it, but he had his reasons for doing so. Good for him! That’s the last time I saw Ken, and I have had only a couple of contacts with other Mark shipmates, sharing thoughts, photos, etc.

Certainly, I would welcome contact with any former shipmates at any time.

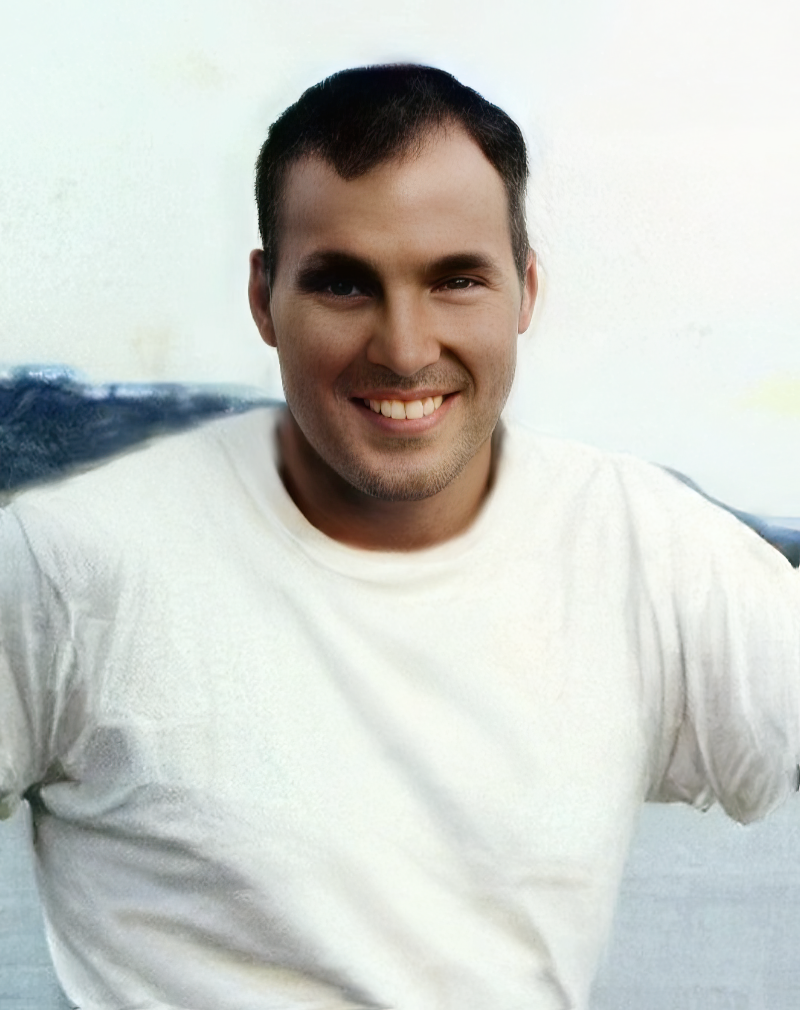

Image:

(Standing, from L to R)

Gary Slavin (Los Angeles, CA)

Jim Tylman (San Francisco, CA)

Mike McCormick (Belmont, NJ)

Terry Moore (Bakersfield, CA)

Keith Peirson (CA)

John “Red” Shroades (Chester, VA) ? s/b WV

Jim Rickles (Wyoming, IA)

(Kneeling, from L to R)

__ Unger (home unknown)

Ed “Jake” Jakubek (Duluth, MN)

Joe Hilliard (Columbus, GA)

Jack White (Canoga Park, CA)

Can you recount a particular incident from your service which may or may not have been funny at the time but still makes you laugh?

A funny story I am fond of retelling about my time aboard the USS Mark (AKL-12) takes place somewhere in the South China Sea in 1966, on our way to or from Vietnam from Subic Bay in the Philippines. It was a moonless night on a rather tranquil voyage, and I was making my way up to the bridge to stand the First watch (2000-2400) in relief of fellow seaman “Jake” Jakubec. As I approached the starboard lookout watch station, I looked through to the helm and thought I recognized the silhouette of Jake standing alongside the helm. So, in an element of surprise, I crept up behind Jake, gave him a big bear hug, and said: “Gotcha, Jake.”

The next moment, I heard words like: “White, put me down!” It was the voice of the XO (LTJG E. F. Mahoney, USNR), who was only slightly bemused by the accidental hugging incident. I’m afraid my claims of mistaken identity fell on deaf ears, but after a while — including some counseling from the XO about when and when not to hug someone — the XO began to see the humor in the situation. Neither the XO nor I ever discussed the matter again.

Need I say that Jake, standing the Port watch, saw the incident take place and was sufficiently amused for all of us. Jake and I had a good laugh the next day . . . and after that. The incident still brings a smile to my face to this day.

What profession did you follow after your military service and what are you doing now? If you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

Upon mustering out of the Navy aboard the USS Constellation (CVA-64) in December 1967 (receiving an “early-out” effective January 1970), I decided not to pursue a career in military service. Instead, I took a position made known by a fraternity brother as a technical writer with McDonnel-Douglas Aircraft, preparing contract specifications for DC-10 aircraft in Long Beach, California. In 1971, I completed my 2-yr AA degree at Orange Coast Community College in Costa Mesa, California, and then obtained a BA (1972) and MA (1975) in geography at California State University, Northridge.

I began a 35-year career as an environmental consultant while still in grad school (1974), but my first full-time position was with a large engineering and environmental planning company in Cincinnati, Ohio, where I learned to be a project manager. I retired in 2008 after managing site selection, environmental impact analyses, documentation, and regulatory permitting for major projects throughout the US and in Spain, Saudi Arabia, and Africa. Projects included the construction of nuclear and fossil fuel power plants, dams and reservoirs, landfills and waste management facilities, mining operations, water, product pipelines, and electrical transmission lines and substations.

From 2005-2010, I served on the Board of Directors for the Vietnam Unit Memorial Monument Fund. Meetings were held at the monument, which is located at the Naval Amphibious Base Coronado (California). While on the Board, I designed the logo for the Memorial, developed a mission statement for the organization, ran the Ship’s Store, and developed a program for the long-term sustainability of the Memorial.

In retirement( from 2008-2016), I was dedicated to genealogical research and writing. I was able to publish four books detailing my family history. More recently (starting in 2016), I learned about, began training for, and competing throughout the US as a senior track and field athlete (primarily shot put, discus, and javelin), winning the national shot-put title at Birmingham, Alabama, in the 75-79 age cohort in July 2017. Unfortunately, I was diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) shortly after that. Following successful chemotherapy under the care of superb doctors and nurses at Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, I slowly began getting back in shape for senior athletics once again. I am working hard to regain my competitive strength, agility, and throwing technique. In 2022, competing as an octogenarian, I was again able to win state-level championships, with my ongoing goal being to become a national champion once again.

What military associations are you a member of, if any? What specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

Actually, I never sought to join any of the more notable military associations (i.e., Veterans of Foreign Wars, American Legion, etc.) following my discharge. Instead, in 2004, I learned about a local (San Diego) all-volunteer 501 (c) (3) organization (Vietnam Unit Memorial Monument Fund, VUMMF) that had been established to honor all of the Navy and Coast Guard personnel who had fallen during the Vietnam War. One such casualty was a good friend aboard the USS Mark during the time I served, Seaman James Rickels. A fitting physical memorial had been constructed at U.S. Naval Amphibious Base, Coronado, California, which is the site of small boat training for those manning PBRs (Patrol Boat River) and was a primary small-boat training location for the riverine military force (Brown Water Navy) in Vietnam. My ship, the USS Mark (AKL-12), was an integral part of the Brown Water Navy, and I could relate more directly to those in that organization, as opposed to the VFW or other such national military associations. Aside from a beautiful wall displaying the names of the 2,564 sailors and Coast Guardsmen who lost their lives during the Vietnam War and plaques memorializing donors and the service members they wish to honor, the site also displays three well-maintained small boats of the type used in Vietnam: PBR (Patrol Boat River, the type used in the movie “Apocalypse Now”); a PCF (better known as a Swift Boat); and a CCB (Command Communication Boat).

At the time, the VUMMF was led by CAPT (ret.) Kenneth McGhee, was a former division commander of a PCF (Swift Boat) Squadron at the Patrol Craft Force in Danang, Vietnam. He recruited me to become a member of the VUMMF Board of Directors. CAPT McGhee turned out to be a really terrific person, and we have become lifetime friends. There were others on the Board with whom I also established long-term relationships, especially Board Treasurer LT Don Farrell, who had served as a Swift Boat captain in the Mekong Delta in the early 1970s. While no longer on the Board, I still make financial contributions to the organization in furtherance of the long-term sustainability of that important monument.

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

My time in the Navy was a point-in-time life experience, and while I definitely don’t regret the experience, neither do I miss it, per se. My attitude at the time was to do the best I could, regardless of the task at hand. That was an outlook espoused by both my father and mother throughout my childhood, so it stuck with me throughout my time in the Navy.

Actually, I was prepared for the Navy’s insistence on regimented/dedicated teamwork due to my having spent 10+ years in scouting programs (Cub Scouts, Boy Scouts, Explorer Scouts, and Order of the Arrow), where the benefits of disciplined thought became apparent through observation and practice. This is not to say that scouting is the equivalent of military experience — of course, it is not — but the regimental aspects are similar enough for me to have been able to readily adapt to the need to follow or give orders and recognize a command structure. That was reinforced during the time I spent in a meaningful active reserve program at North Hollywood Naval Reserve Center before going on active duty.

Today, I still welcome a bit of regimentation in the structure of my personal life.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Navy?

The Navy offers a great opportunity to learn more about yourself and the world, physically and culturally. I advise new recruits to learn how to accept and give their best to their assigned tasks — even sweeping the deck or painting a bulkhead. Ask questions and show that you care about your role, however large or small. Those actions will not go unnoticed and will lead to other opportunities as time passes and you prove yourself to be a valuable asset to your command and to your shipmates. Moreover, military life helps broaden one’s worldview. Forget about egos. The Navy is all about teamwork, so try to become a dependable member in whichever team you are assigned.

Do yourself and others a favor by taking your commitment to the Navy seriously for your entire length of duty. Always consider the Navy as a possible career, and, as such, strive to learn as much as you can from others and from your own experiences. Above all, be cooperative and dependable, and show that you care about the quality of your performance. Those traits help to characterize you as a person, a good shipmate, and someone suited for advancement.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with.

Frankly, I didn’t quite know what to expect when I first began to provide personalized responses to the probing self-guided questions in “Service Reflections.” However, I found that I was able to recall more than I thought I would. Consequently, it also allowed me to reflect meaningfully on that formative period in my life. In doing so, I realized that this series of essays would not only be there for other veterans to read but would also represent a legacy for my family, who really don’t know very much about my Navy service experience.

Like many others who served in Vietnam, besides my immediate family, I was not welcomed back, nor did anyone say, “Thanks for your service.” I quickly realized that it would be best if I didn’t discuss my time in the Navy with anyone outside my family. And so, I didn’t. It wasn’t until I heard about and became actively involved in the management and upkeep of the Vietnam Unit Memorial Monument in San Diego 40 years later that I again began to think about my time in the Navy.

Now, with the help of TogetherWeServed.com, I have at last taken a deep enough dive into my Navy past to recognize that there is pride and gratitude among the many other emotions and memories of my Navy service.

Thank you for this opportunity, TWS!

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

Hi Jack, my name is Jerry Renolds, the son of Ken Renolds. I just read your profile that a family friend had discovered. Thank you for sharing your story, it was quite a surprise to read my father’s name unexpectedly. I hope you and your family are well. If you are up to it, I’ve included my email address for correspondence.