PRESERVING A MILITARY LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

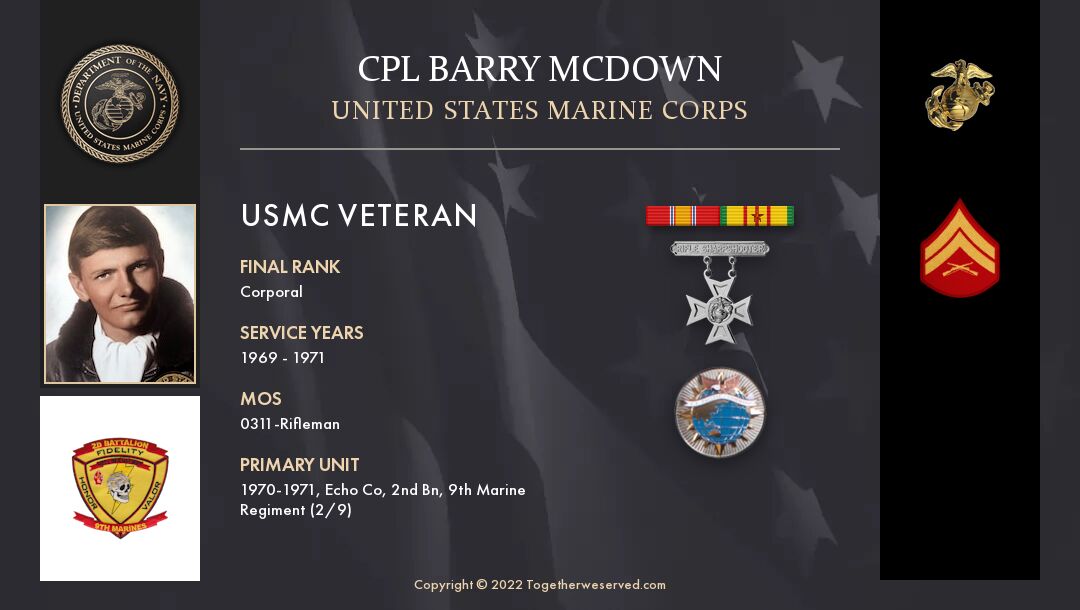

The following Reflections represents Cpl Barry McDown’s legacy of his military service from 1969 to 1971. If you are a Veteran, consider preserving a record of your own military service, including your memories and photographs, on Togetherweserved.com (TWS), the leading archive of living military history. The following Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Military Service Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life. Start recording your own Military Memories HERE.

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Marine Corps.

Within 90 days after Richard Nixon was inaugurated, he sent me an excellent thank you note for being 19 and indicating that he would be pleased if I would show up for work. He very much insisted I report for the draft.

After some study of my very few options, I took the Air Force entrance exam and all but aced it, with a score of the second highest. I discovered this allowed me to be placed on the waiting list. In that, the Air Force took two men a month from my city, a population of 600,000. I would be required to wait 120 days as six bright men were in line before me. The President wanted me sooner than that.

So, I walked across the hall to the Marine Corps Recruiter with several questions he seemed well prepared to answer. He even volunteered that, although I would arrive in Vietnam, I could avoid landing in the Army if by volunteering for the Marine Corps, I would, in short, work, become a man, and thus it would appear I was not dragged kicking and screaming by the President.

I capitulated. Coming from a family that knew responsibility well, I enlisted in the Marines for one reason. The Marines have a reputation for success. Very few enemies live to regret discovering they were surprised by the Marines’ arrival. I believed if I trained for war, I would be safer if I learned how winning was accomplished well.

There’s a back story. My birth father, whom I barely met, found little time for me. He is, however, buried in Arlington, having served and retired from all five services. His first bronze star was as a Marine in Korea shortly after I was a fetus. Another man I called Dad from when I was six until he passed in ’92 was decorated on Guadalcanal and Okinawa as a Navy Corpsman assigned to patch up, or declare dead, Marines. His Commander was Chesty Puller. My genetic Grandfather was a paratroop and code breaker in the Philippines and held even after the war to ferret Japanese that were unaware WWII was over.

Grandad cut hair for a lifetime after the war. Dad came from a family of ten, wheat farming and cattle ranching in Oklahoma, and Mother was pregnant with me four months after turning 15.

In 1969, there was the promotion of Communism on most college campuses, and I was the first person in my family that had ever graduated from high school.

I was engaged to the girl who was our co-valedictorian.

But, if you ever wonder why a man steps on the yellow footprints of Parris Island, it’s because it’s the only place where two men have each received two medals of honor, Dan Daily and Smedley Butler. If you step up to that, there is a possibility you can learn how they did it, and you already know why.

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

Just after I received my Vietnam Service Medal with an attached bronze star, I rotated back to Okinawa, where, comically, it was time for me to requalify with the M16.

By grace, on the first day of firing prep, there was a doldrum, not even a whisper of wind. As it was not qualification day, I broke the range record unofficially, sending me to Marksmanship Instructor School. A magazine in the black on rapid-fire is unforgettable. Translation: “You have what it takes to become a sniper.”

While I had served honorably and well, I had known one too many deaths and was not attracted to quietly causing them when it could be challenging to identify the targets. After a year without a phone call, I looked forward to my freedom bird just weeks away.

One Saturday morning long before, when I was seven, I jumped up and down on my parent’s bed, yelling, “I won, I won.”

They discovered I had entered a television drawing contest and needed a ride into town. I won the Hallmark Art Contest when I was seventeen, was accepted at Yale at eighteen, and was drafted and engaged to be married at nineteen.

The college G.I. Bill was attractive. I wanted television to lead this planet to peace. Some told me that I was an artist, and I learned well enough how to help.

Situation: Know where you are before determining where you want to go. Mission: Favorable condition, Earth. Execution: Heart and Soul.

The Marines are not looking for a few good men. The Marines have already found potential, and it never leaves, for it is nurtured for life; having been taught, all of us must find and obey the truth.

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

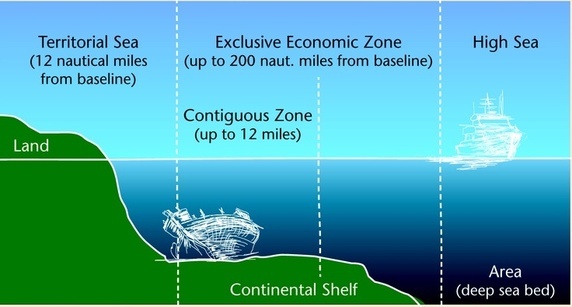

My unit was engaged in Operation Commando Hunt V, a coastal patrol of the Contiguous Waters of Vietnam.

During our engagement, we were invited at sea into the clutches of Typhoon Joan, with 105 mph winds, the fourth most powerful storm in Pacific history.

The bow and stern were in towering waves with air under the keel, rolls 30 degrees windward, 30 degrees lee. She killed people, and we survived.

Fifty-one years later, thanks to Congress, I would be awarded service-connected disability regarding the damage done by blue drums with a wide orange stripe, the defoliant agent orange, bursting and splashing against our bulkheads for two days.

More often than sometimes, men, who have known fallen comrades, are slow to claim any injury, and just as often, they are invisible by their quiet. It is good to occur to a man whether he is an ambassador serving well or not.

The people of South Vietnam asked us if our Country was humanitarian enough, and we offered with our lives how much we hoped so.

Vietnam is not planning any wars any time soon. Nations have paid for peace with men from their family tree since the beginning.

Did you encounter any situation during your military service when you believed there was a possibility you might not survive? If so, please describe what happened and what was the outcome.

I have never met a Marine who was sure he would survive his service.

It is the quiet, solemn truth.

Death is not the greatest fear, for death ends terror. While several times I thought I was nearing death in the Corps, it is a shame rather than fear that survives.

We fear our performance will be inadequate, that we will ever be the cause of someone’s suffering. It is the burden of service, the responsibility of honor.

Forever haunting is how much we matter.

Just before being deemed a Marine, graduating from Parris Island, our senior drill instructor killed the Private standing next to me after calling us to attention. Roundhouse kicking him with the first strike in the kidney. Our teacher repeated the brutality as the Private lay unconscious.

There was an attempted cover-up, and every cohort was Court Martialed. I was, at the time, the Platoon Guide and was called as a witness. I was asked to assist in making the rack of the absent Private and slept next to it until leaving the Island for Nam.

Finding leadership sufferable of disdain, I have found limited solace in avoiding inattentiveness and the poverty of misguided zeal.

Acclimating to the jungle in a Subic Bay firing exercise, the feeding hand of our man disappeared as he fed a second mortar into the tube, still holding the first fed and unlaunched. Mortars are rockets, and there are deaths long before life ends. There is the torture of the inability to escape.

You may someday hear of the Contiguous Waters, voices from Combat Campaigns of Vietnam. You may hope to remain aright, searching the borders of performance, of conflict, and avoiding not terrain but an uncharted edge, not the coast but the bottom of the sea.

Welcome back to typhoon Joan, souls in service, mettle in steel.

Fear? The empty chair at Thanksgiving, an engagement ring treasured until a desperate day, something in the future you will not attend, not death, but the last phrases of your prayers.

I was so short I could do pullups on a staple. It was days, not months. A man does the math in hours.

Relaxing off the beach of Okinawa, awaiting my freedom bird, a Pacific lionfish nailed me. It is recorded as the second most pain a person can experience on this planet and the first – male platypus venom injection.

The nurse said, “If you make it to morning, you might not lose your hand.” (Swollen to the point of shiny)

The closest antidote? Honolulu. Flight impossible.

A man hopes he is allowed seconds to thank God.

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

Comparing my duty stations, a favorite with least, it is moments rather than places that linger.

Esteem comes to mind.

It helps me to discuss sorrow first and joy following because the tonic of delight helps me maintain hope.

War is cold and peace warm.

We often hear the word patrol. Still, few understand contiguous waters. Our vessels moved quietly as recon surveillance, east of anything that penetrated the actual border of Vietnam, twelve miles at sea. At seven miles, you can see the coast. We got a little closer than that.

On the west border, the Ho Chi Mein Trail doubled as both supply and diversion, with bicycles and trucks bringing personnel, weapons, and ammo south. North Vietnam aimed their supply down their West border under darkness.

Not a whisper from The Stars and Stripes tipping off the enemy, we were on to them, not a word from Cronkite. A well-funded Communist VC knew the advantage of a ship’s hold over a bicycle basket through the jungle.

In January, Marines, impervious to 110 degrees in the Philippines, patrolled Contiguous Waters North to a climate well below zero, halfway up Mt. Fuji, Japan.

War begins at wit’s end.

A classified, long untold story of the Vietnam War now whispers the difference between combat and a combat campaign.

The familiar story is the Ho Chi Mein Trail, a stealthy enemy delivery in and out of the Cambodian border. Brave teenage girls drove camouflaged trucks and steered bicycles in long lines, slowly supplying the enemy.

Many of our Army have long tried to quiet the trauma in their hearts from skirmishes, remembering dead children, nightmares where the borders of humanity lie. The memories sometimes held until their lives were taken, months or decades later.

This brings me to the campaign that has frustrated long-silent veterans who deserve a salute. For a lifetime, those assigned to Contiguous Waters have too often been erroneously called Vietnam Era Sailors and Marines.

After fifty years, their actions were declassified by the U.S. Congress. Recognition for preventing trained personnel and bulk munitions from arriving to support the enemy, and disclosure that the Ho Chi Mein Trail became necessary because sailing through mined water, the United States was halting anything afloat at sea. In 2019, Congress changed the law, notifying men who had held silent that they were now appreciated. “Your country just announced you had served in the war.”

The Contiguous Waters was Combat. VA counselors were hearing it for the first time, if they heard it at all.

Patrol after patrol, our servicemen launched from the Philippines in 110 degrees and landed on the coast of Japan. While they trained in Admiral Byrd gear at the base of Mt. Fuji, the patrol behind them would commence. In that fire and ice, I knew my least favorite moments of service.

One of the most important missions in the Vietnam War was accomplished. My least favorite memory is when we were in fourteen-man tents, two feet of snow in eleven-degree weather, when a beer ration was chosen to lift morale.

My first fire team leader and I decided to forego the festivities, opting for warmth in mummy bags out of the wind.

We could not know why a bayonet sliced through our tent. Five men entered through the orifice. They kicked and beat my team leader with fists and mop handles until he was unconscious.

Awakened by the ripping through the canvas, I struggled to unzip my sleeping bag, hoping to help my man. When I got to him, the marauders were in another tent.

John Barleycorn had revived John Brown.

Combat and cold had resurrected war, the mutiny of racism, and the discard of humanity.

I was Corporal of the Guard that night. Fourteen men logged into the brig. I had never felt that much shame, but the Good Lord is the messenger of the kingdom of kindness. What would follow was healing. Joy.

Demers was the team leader’s name; his broken jaw and ribs were just beginning to heal on his first liberty after our combat campaign. Aimed to walk two miles away towards a train to Tokyo, we muttered about the long haul and short freedom.

I made a habit of escorting men on their first liberty, sometimes to allow them a translator, other times to show them pitfalls to avoid. I was proficient in the language of drawing stick-men if necessary, helpful when communication broke down.

Halfway down the mountain, we came upon a Datson that had been poorly piloted, dropping both right wheels over the edge of a concrete drainage ditch four feet deep. Japan is frugal and has no guardrails.

I suggested we attempt to free the vehicle while the driver tried to steer. All the grunting failed because we were required to lift it over our heads.

Our savior was the arrival of a Japanese Colonel, pulling up and setting on his parking brake. The three of us then yelled a chorus of Ooorah and Bonsai as we achieved the first wheel back on the road and the second wheel.

Grinning a mouth full of glistening gold teeth, the Colonel coached the driver in Japanese, “You think “Arigatou gozai mashi ta” in “Engwish,” say “Thank you.” Americans will say, “You are welcome.”

I reciprocated by telling Demers that in Japanese, “You are welcome” is “dou itashimaste.”

The driver uttered, “Yu welcome,” upon which Demers said as cordially as he could muster, “How’s your mustache?”. It was too funny.

The sweet thunder of a belly laugh roared at the conflict. Finding they must have messed up in communicating to the Japanese, the driver and Demers joined the Colonel and the Corporal, almost crying with joy.

Happy still in my fortune of attendance are the grunts, the sparkle of a mouth full of gold, and the certainty the driver was on his way to the Ambassador.

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect back on to this day.

Virtually lost in history are clauses observed by signatures set down by Imperial Japan on September 2, 1945. One of their stipulations was that Okinawa would be surrendered to the United States for no less than a half-century. In 1995, she was gratefully returned.

I was forced to write up one of my men just before my Vietnam tour ended. He would remain in Okinawa after I rotated.

His name was Lombardo, nicknamed Lobo, after the Crazy Wolf.

I never did cotton to anyone threatening to write someone up. I thought it was extortion rather than leadership. So, I reckon I was writing something to help Lobo. He was giving and deserved to go home.

I did not see it that way at first.

A Captain boasted over drinks in a barren officer’s club that Foxtrot had field marched just over thirty miles. Our Captain of Echo Company heard it, believed it, and never said a word.

We then guarded an LZ for a couple of weeks, expecting the same choppers that took us there would return to take us back. Nope. Semper Fi. Saddle up. Hump.

The eastern world is a non-Euclidean geometry of deep valleys and high hills often seen in ancient rice paper paintings. Up and down, we went with the heaviest packs issued; rifles, rations, bloopers, .50 caliber saws, ammo, and taking turns with a PRC-25, a 23-pound radio.

Near the middle of our commute, the order was given to halt, split ranks to each side of the dirt road and chow down on a C-Ration.

Struggling to remove a sweat-wet pack from a soaked utility jacket, Lobo pipes up with, “Hey, Lieutenant!”

Lieutenant John Staples, both Lobo’s platoon leader, and mine, looked at me and said, “Did he go through you?”

Sharply, and before I could speak, Staples challenged, “You have something to offer, Lombardo?”

Lobo, with a smirk, asks, “How far have we gone?”

Staples: “Map says 38 miles.”

Lobo: “Well, how far do we have to go?”

Staples: “Map’s total is 52 miles, Lobo.”

Lobo: “Well, hell, I’m tired. I think I’ll turn back.”

The Captain was not privy to this conversation until I realized the distraction from blisters on my knees and aches to the bone might be soothed a mite, thinking less of how far I went or had to go.

My pen chose a trail. Hoping for excellence, I told the Captain what he had missed up there in front and how refreshing it was to receive nutrition.

I found Lobo on this wonderful site called Together We Served. It’s been fifty-two years since fifty-two miles, an accomplished road on which Lobo meritoriously promoted everyone.

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

During our Vietnam tour, we would salute anyone awarded the Medal of Honor. It was obvious to us that few live to receive it, indicating its offering humble. Still, among the ranks was a common curiosity as to why a Purple Heart somehow escaped this courteous tradition. You see, in the barracks, in the field, there were men perplexed knowing you could receive five Purple Hearts from a graze to limb loss or one Purple Heart where sad bearers of bad tidings would notify your mother you were dead. Few hope to be decorated, though all understand the sacrifice.

The grail is the capacity to perform, to be assured you can protect those you love against the adversary. It is easier to go where you are ordered if you are ready before you embark. You must undertake and succeed, and neither are functions of pride.

Shortly after our combat campaign and at the end of our class at Regimental Non-Commissioned Officer School, I was chosen as the number one man and subsequently promoted to Corporal. In the Corps, that was understanding of blood stripes, red running down your trousers, in remembrance of Chapultepec, the Alamo of the Marines, a handful successful against a legion. It is wonderful to find honor.

Back then, when promoted, you made a gauntlet, now a punishable crime. Your Company split ranks into two columns, each of a hundred men. Your mission, march through the middle while every man standing was allowed the opportunity to symbolically pin on your stripes, two-by-two, slugging you in the arms at whatever force they chose. Most would have you never forget it. Often, officers, the following morning, would forgive you for your inability to offer a salute.

One Lieutenant forgave me for not saluting, and one who did not inform me they had exacted a wager. My Platoon Commander said he wagered that if they sent me to Division NCO School, I would get somewhere in the top five. His nemesis shook, saying I would not.

To a class among men from the Pacific theater, I was sent by my Company, Echo 2/9. I fared well enough to enjoy the memory.

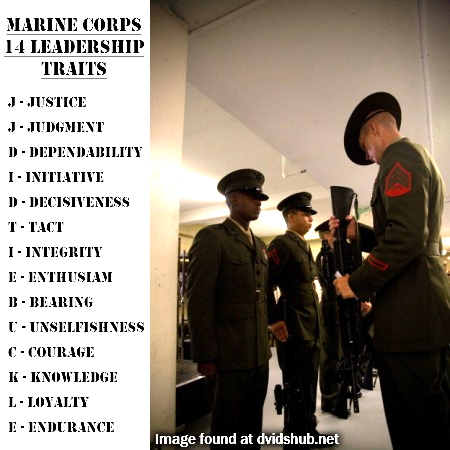

There is no stone unturned in Marine Training, particularly regarding leadership. There are many ways to go from point A to B, and there is one to arrive at esteem. Study.

Every night after chow, I would walk to the drill field. “Stop, stop, stop!” my drill instructors’ voices haunted me as I would practice the 20 moves of close-order drill taught in boot camp. Teaching myself which foot started this command and ended another, I sought to understand well enough what was coming, the final assignment before graduating. Each of us would drill the other contestants while being overseen by multiple clipboard-bearing monitors, observing and grading every step.

Alone each evening, each practice, I got a little better. Pursuing excellence, I was befallen by an epiphany. Perfect is why practice exists, and you cannot find the best until you understand why you are not there.

It occurred to me that with a little rearrangement of the order of commands, I could seamlessly sew them together by calling the preparatory command during the execution of the command I just called, leaving zero steps wasted. I hoped I had enough time to find where every step could be called and executed without wasting one.

On drill competition day, men were all over the board. Some fared well, marching men halfway across the drill field; others stuttered us off into the grass. Many a clipboard tick-marked each leader staring at his provided list as he read what he should call next.

My turn.

I folded the list, buttoned it in my pocket, and said, “Platoon, Attention.” Note to note of flawless music, after 20 moves of the drill; the platoon was less than a hundred feet from where they started, Platoon Halt. Clipboards started receiving marks.

At the time, it felt wonderful that my Platoon Commander had won a fin, “fydollaz,” in a day when a private didn’t make a hundred a month, but life can surprise a man, and it can astound.

I was home and in college again by 1972. My great surprise came after 1992.

I responded to a handwritten note on a bulletin board in an antique store, “Old Stamps for Sale.”

The following is a letter I addressed to the President in a package containing priceless instruments, the package I had the privilege to discover:

You have stumbled upon a love story. It’s a story carried not only by words or steps but by music. It’s a story of passion and precision, about wanting your love to be as perfect as possible.

There once was a boy so weary of earning achievements with the violin that he complained to his father that he would prefer to choose another occupation in his professional time.

In fatherly cunning, a secret bargain was made with a baker to work the fingerprints off the boy, assuring him to rise before the chickens and eat supper in tearful gratitude. The boy’s name was John Philip.

Never having graduated to being an expert on any particular string or any of the remaining instruments to be encountered, he played second seat for The President’s Own at thirteen.

After stepping off thunder and lightnin’ from the train to the theatre house on the soil of the carpets of kings, there was a friend by the name of George Frank Ford. Everybody liked Frank.

Frank marched beside the man that wrote and produced the longest-playing musical in history, “The Music Man.” That famous Beetle tune, “Bells on the Hill,” was written by that man who proudly marched beside Ford on liberty call.

Long after Ford’s footsteps, there was a notice on a corkboard in a curio shop, “Old Stamps for Sale” and a number.

I followed by car phone past the Brahman cattle along dirt roads benchmarked by poles painted white; the importance of trails marked only by the tracks, the countryside, near the oldest city, St. Augustine.

She handed me a stack of colorful souvenir postcards, the kind that makes one bust out into a giggle. They were the attempts of a member of John Philip Sousa’s Band to jot notes to Mrs. Ford that her music echoed and inspired him between their interludes.

Not a completely wise man, but rather a scoundrel, in an effort to care, I pressed her to speculate further on the history of the man who had penned the love notes to the lady.

Perhaps, wiser than most of us, she spun her web of pretended ignorance in her purest heartfelt hope she could get these notes before the world understood. Her conscience hope was riding on it, and so was mine.

She led me to the secret treasure of a man who “made his livin’ on the road.” My heart pounded in perfect euphoria as if I had heard a cello come to life.

There, before me, lay the cherished receipts of the single friend who had been entrusted with the instruments of the finest virtuosos as they passed into time. The most obvious effect was a full uniform; the cover blouse and trousers in regal brocade faded back in my mind to the time when they must have dazzled and steamed in the sun.

“This was Sousa’s father’s,” she said. She gracefully offered a solid silver flute, “Buffet Crampon & Company” Paris. Behind it, an intimate tympany tapped on my soul.

There were two more flutes, one a piccolo, both hand made. Finally, there was an obo inscribed in gold, something in French about a jury member.

Like the peace that comes when a mirage evaporates into a genuine tall drink of water, I appreciated the blessing of actually being there.

Though I thought I was of no consequence, I bragged of my membership in John Philip Sousa’s band, the Marines. I was becoming part of the recovery of the March King.

I felt wonderfully important as these artifacts reminded me that music represents knowledge moved, with the fewest number of steps, almost as if merely listening to music makes an efficient progression of mankind inevitable.

The lady confided in me. She told me that the moth holes were from many years of hope. She said my enthusiasm had touched her. She resolved to give it all to me, lock, stock, and barrel. “You are the kind person that will get this to the right place,” she said.

Just then, her strapping son arrived home. He studied, shook his head, and said, “Dad is not going to like this.”

“When will he return?” I asked.

“He drives for about ten days and will be back tomorrow.”

The woman would not yield to an Indian giving, and she stood pat on the authority of her man loving her and by that sacred notion, “She was certainly empowered to speak for the two of them,” now the three of them.

I said, “Okay, here’s the deal.” I said, “Heck.” I didn’t know what to say. Finally, I said, “If you are absolutely sure you entrust me with these treasures, then I will do my best to place them well, but the moment he returns, you both tell him immediately, and after a period of thirty, no ninety days; if you have not called to receive them back from me as freely as you have given them, then I reckon it is my job from then on. Fair enough?”

“Done,” she said. After that, I always said done in a bargain.

Early in the seventh month, she did call and asked me how I was doing. My conscience soothed some. No, the truth is better than fiction. I felt greedy, and I never wanted to feel greedy. So, I began to look into John Philip.

I ordered his autobiography. I watched Robert Wagner in a movie about the soul, “Stars and Stripes Forever.” Sousa.

I had a mission. I knew how to use books, and the University of North Florida taught me how to talk with anyone. Call.

The inventory is priceless, Ladies and Gentlemen. It turns out that for the Paris Exposition at the turn of the Nineteenth Century, there was a contest, the goal, a sound, the plan, and the finest players on the finest instruments. Compete for the finest instrument. Be the most refined player. The orchestra is in the “x” position.

A beautiful carving from that triumph belonged to Richard Messenger, the messenger mentioned in the Wagner Movie. The Messenger obo, Juried to be the finest, was passed on to Frank.

The Piccolo was made especially for Robert Cavally, as evidenced by records of sale, The Haynes Company, the cradle of Liberty, Boston. Cavally was the best. Ask Haynes. They said it made them feel good just to hear his instruments had been found. His flutes? Yes, someone gave them to Ford.

And then there was that other flute, the one that went back to 1857, three years after John Philip was born; the flute that belonged to the fellow that liked to make deals with a Confederate. Sousa’s father. Everyone liked Sousa’s father. He married the girl that made John’s favorite meal the night they learned from a baker how precious a son could be.

John Philip’s lessons from the man of leaven grew into a levelheaded notion about forever.

When the President of the United States asked him to play a few tunes for tea, that boy anchored his heels against the White House Steps and marched away the songs in his soul.

By the time he was beyond the sight of the gates of glory, no one had a clue where he was going or why. But, when he got there, there was an invisible x on the deck, and by the dawn’s early light, Ford’s toes were in the same spot that Sousa’s heels had been; and right behind him was ten million miles of the glory, glory, battle hymn what-cha-call-it of the best dadburn Dixie that ever was or will be!

Note Last. Step first.

“Before you, ladies and gentlemen, the pace these United States shall march into eternity,” the President said with his eyes.

For a long time to come, everyone else just said it, the only way they knew how.

“Love him.”

You see, while they played in the pounding sun or stood soaking in the rhythmic rain, his heart recorded the grace and gave it to the girl at the other end of the lines.

I have often thought of the Fords at the end of the train and what it takes to become someone everyone likes. I have often thought of how wonderful it would be if there were a place in the Smithsonian for the treasures of Frank Ford and the people he taught how to give.

Before you are some remembrances of people who willed their fingertips to crawl across the Universe to pray like little John. “I love everyone. One more time.”

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

As a veteran of two combat campaigns, I received medals and formal awards presentations and took home memorabilia, like all Marines, with a DD214.

It was an informal meeting that stayed with me. In this writing, I am 71, and it was then 1971.

Soon after I packed, my unit would be sent for an R&R that I would never have. I would be sent to a casual company as a member of the Marine Corps Super Squad, of which there are at any given time only 42 members, one squad from each Division. Later, I would receive notice of my freedom bird, a euphemism for the craft that would take me halfway around the world home, from those we fought to those we had hoped to serve.

A voice came after a knock on one of two wall lockers bordering my hooch.

“Corporal Mack, could we speak to you for a few minutes?” I pulled back a privacy curtain, answering, “Of course.”

There stood the squad I had led. The “Old Man,” the oldest among us, Sims, aged 23 years, a comedic transfer from the Air Force into the Marines, spoke, breaking the silence. “Corporal Mack” we just wanted you to know we believe you are the best NCO this Marine Corps has ever had.”

At the time, I prayed I half deserved it, and that left a mark.

We all know I was blessed to have been in their company, the Country that thanks us for our services.

Approximately 25 years later, I received a thank you note authored by an extraordinary Commander and his wife saying, “You were good to remember us in such a thoughtful way. We sincerely appreciate your kindness. Thank you for thinking of us.” – Ronald and Nancy Reagan.

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

The most outstanding leader I encountered during my enlistment in the Marines was First Lieutenant John Staples, my Platoon Commander during my Vietnam duty. Among the finest people I have ever known, he inspired with sincerity the highest aspirations a man can achieve.

What profession did you follow after your military service and what are you doing now? if you are currently serving, what is your present occupational specialty?

Any pursuit a man follows after serving in the war is knowledge, the inseparable arts, and sciences. I followed the sciences, and art followed me. I enlisted in the Marines with a reputation for both.

I planned and succeeded in profiting from my skills by honing them with the G.I. Bill. It occurred to me that every period of history was dressed in artists’ renderings of either truth or fiction. It appeared obvious to me which one was which, that propaganda was transparent and the achievement glaring. So, hoping for payment, I turned my hands to effort.

Through that decision, I met and fell in love with America. I painted no pompous, perfumed kings, though there is an almost surreal portrait of Gerald Ford holding what most kids today would identify as a cell phone transmitting to the stars. I tried my hand at winning the Duck Stamp Contest, a purse of three million dollars. Although the Department of Interior called my home and told me I had achieved the finest painting they had ever seen, the Post Office had punctured it, and it had been marred from its intent and, on the agreement, disqualified. I rendered a potter gently finishing the lip on a bottle and sent it to Ronald Reagan, asking him to bestow it upon a leader in the middle east to encourage the area to understand what the people of America were about.

But, I have most often been remembered as a sign man, for the States are a sign shop first. Somebody painted a number on a Conestoga to account for the missing. Another laid a gold leaf of candy in a window where laudanum was under the counter for vets. A handful of men were assaulted by the neon in Time Square, on television with color, and, yes, someone painted Apollo on a booster, but mostly a sign shop is a warm smile greeting someone who has never been on a desperate plane.

That, someone had just maxed out two credit cards and swept out a small building that could become his dream of being a businessman. Your smile is to encourage him that he is not crazy, that America loves a soldier of kindness, someone who has figured out the family is huge, hungry, and needed. He is finding his hunger in what feeds, grows, and honors, and he figures if he asks for his name pretty big and in red, the fellow with the smile will help him shorten the copy because all that sounds expensive.

And the new businessman asks, “How much for a 4×8 saying The Gettysburg Address?” And the sign man says, “Much less than you would ever dream of, and it will be here for tomorrow. Quote me on that. It will come in handy.”

What military associations are you a member of, if any? what specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

I have two friends, one in his nineties now, Frank Purpura, and another slightly younger than me now of 71 years, Pete LaCombe. They are lifetime members of Veterans of Foreign Wars. They are upstanding, down-to-earth, and memorable for their kindness, particularly in that they have seen combat, that taxing endeavor where one must be trained to do the ultimate harm.

Frank had a barbershop for a career and became a pleasant fixture in the community. He still answers the phone when I call, and it’s a landline on which we converse for some time. Pete is a kind of VFW historian and very much an old friend. They met me around a round table in Jean’s Restaurant for mornings drinking coffee and rustling newspapers. One day, they approached me with a bargain. “If you come to our VFW membership meeting on Tuesday night, we’ll teach you all about poppies and give you a free membership for a year.”

I was pretty messed up then, and the comfortable comradery ensured the meeting. Before long, Pete helped me file a VA claim regarding compensation for Agent Orange and PTSD. My mother held that paperwork until I found it among her effects upon her passing.

This past year, 2020, Congress recognized Contiguous Water Vets were Combat Vets and instructed the VA to compensate us. Local VA representatives are retirees from Desert Storm and don’t know what a Nam Vet has endured or how to reference evidence or even find it.

Though it matters, it’s painful.

But, the brotherhood of those who have served is without frivolous or innocent amendment.

We cared, we went, and there was a cost we were happy to face.

It is our thank you for serving us.

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

One of the more pleasant observances I have had regarding those having served in any military branch is that most begin sentences over coffee with, “When I was in the service.” It is a relatively warm comment because with this preamble, they humbly, coincidentally, take care to pay respect to all who have served, and they choose to disclose later which service they choose.

This has everything to do with how grateful I am for the simplest gift I received from my time in service. It is referred to as a five-paragraph order, a system whereby the President can give an order, and an entering private, seaman, airman, or now space adventurer will hear precisely what the President ordered.

We refer to it as SMEAC. It is not an anagram, for that is rearranging the order of letters, such as cinema, into iceman. Order in SMEAC is important, as the order is important in NASA. Both groups of letters are acronyms.

Those who have served will remember the `Situation, Mission, Execution, Administration, and Command. I defer to boot camps to expound on the details, but I remember the value of knowledge of this system as it relates to the question before me: “In what way did the military influence my life?”

Situation: One must find out where they are before determining how to go anywhere. The mission follows the situation, and command is last because even in peacetime, one must be in command of themselves, doing something.

I have served businesses with that plan, and I have run my own business with that plan. I have even compared that plan to Robert’s Rules of Order in hopes of understanding my family, yours, and ours.

So, an acronym can be helpful. Another important one is ROY G BIV, the familiar first letters of colors. There may or may not be a pot of gold to be found, but when a rainbow appears, or a harvest moon rises, we find that no matter what science may say, man did not invent the wheel, and he was trying to figure out where he was and how he could go somewhere.

At a stop light returning from an appointment, I checked the time, and my iPhone warned me I would not receive messages while driving. So, I pondered just how that worked, millions if not billions of people receiving similar warnings from an array of satellites, knowing precisely where they are at any given moment and their speed traversing the planet. At first, it was a little scary. And then it occurred to me that the Good Lord had Wi-Fi long before Eve took the first bite.

When folks thank me for my service, I am reminded how meaningful services have been and may well be, and I quietly thank all those who have shared with anyone.

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Marine Corps?

Carefully record the accomplishments of others.

In what ways has togetherweserved.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with.

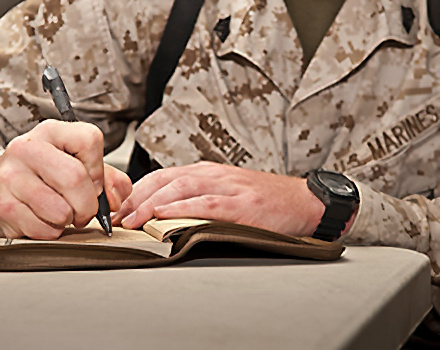

The Together We Served Team has a place for Veterans to record their military history as it may replace their lost DD214.

Yes, our locations, graduations, awards, medals, and commendations glimmer against our challenges, our wounds, and our ranks, but TWS encourages something equal to or greater. In this place, one can journal emotions and remembrances.

These reflections are the words of what it was like, of what it could be like, and those hopes are precisely what people will want to know. They will want not only to live but to contribute generously to help others.

In the song, Marines tease about the Army and the Navy looking upon Heaven’s scenes as we guard the gates, but every service to this Country is part of how we get there.

Truth is present tense. Together we serve.

I thank you all for your leadership.

PRESERVE YOUR OWN SERVICE MEMORIES!

Boot Camp, Units, Combat Operations

Join Togetherweserved.com to Create a Legacy of Your Service

U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard

Yours has been both a fascinating, and enjoyable Service Reflections. Thank you for sharing.

Semper Fi

Boz