Women have been involved in aviation from the beginnings of both lighter-than air travel and as airplanes, helicopters and space travel were developed. Women pilots were also formerly called “aviatrices”.

During World War II, women from every continent helped with war efforts and though mostly restricted from military flight many of the female pilots flew in auxiliary services.

Americans Refused to Believe the War Was Inevitable

Like most Americans in the late 1930s, President Franklin Roosevelt was not eager for the United States to get embroiled in a global military conflict.

However, unlike fervent isolationists, he felt it was inevitable over time and began taking some steps in preparation for such an eventuality.

He pushed Congress into doubling the size of the Navy, creating a draft (approved by a close vote of 203 to 202), provided military hardware to friendly foreign nations, and ordered the Navy to attack German submarines that had been preying on ships off the East Coast. Congress also approved an acceleration of building warplanes. Many airline pilots holding reserve commissions were recalled to active duty to fly them as they rolled off assembly lines.

Even with all the preparation, many Americans still refused to believe the war was inevitable. Then on a quiet, peaceful Sunday morning on December 7, 1941, Japanese naval and air forces launched a surprise attack on the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor. More than 2,400 military men were killed, 150 planes destroyed, and eight battleships were sunk or badly damaged.

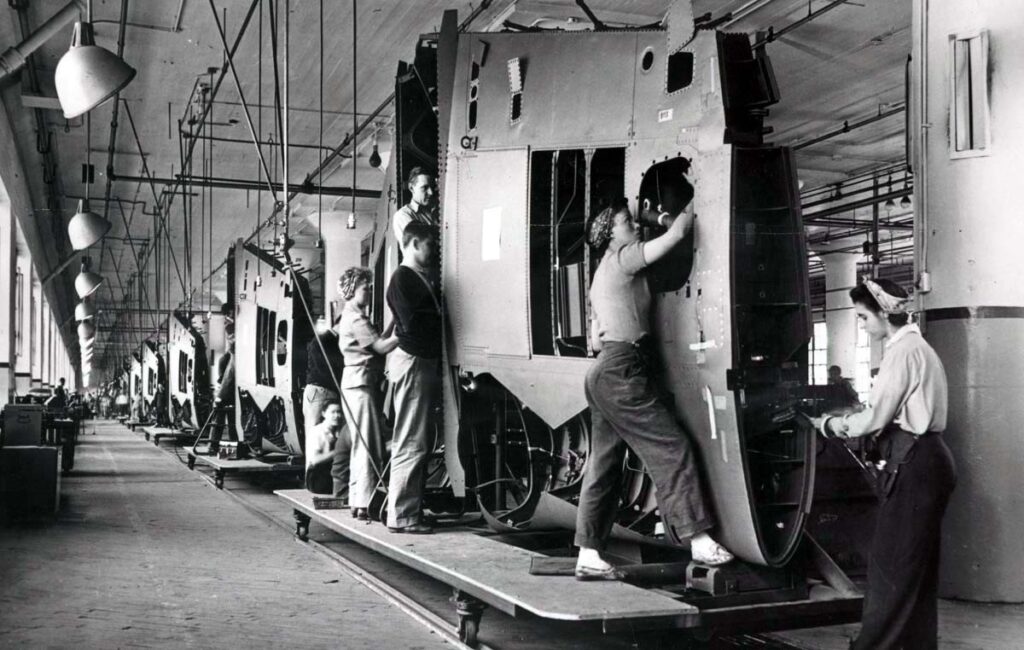

More Than 310,000 Women Pilots Worked in the U.S. Aircraft Industry in 1943

The next day, Monday, December 8, calling the sneak attack a “day of infamy,” Roosevelt announced the United States would join World War II. Three days later, on December 11, 1941, Congress declared war on Nazi Germany. It was a time of fear and time of desperate haste for America to mount a war machine that did not exist since World War I.

The draft was greatly increased, and with every available man being inducted, war industry jobs went unfilled. American women stepped in to take their place, taking over a wide variety of positions previously closed to them. The aviation industry saw the greatest increase in female workers. More than 310,000 women worked in the U.S. aircraft industry in 1943, representing 65 percent of the industry’s total workforce (compared to just 1 percent in the pre-war years).

The munitions industry also heavily recruited women workers, as represented by the U.S. government’s “Rosie the Riveter” propaganda campaign. Though women were crucial to the war effort, their pay continued to lag far behind their male counterparts: Female workers rarely earned more than 50 percent of male wages.

Henry “Hap” Arnold Categorically Denied the Need to Use Women Pilots

As hundreds of military planes of all variety were coming off the assembly lines, there were not enough certified pilots to fly them. Reserve flying officers were recalled to active duty, but there was still a shortage. To address this shortage, a group of government officials and military officers considered using certified civilian women pilots to ferry aircraft from the factories to overseas where they were needed, thereby freeing male pilots to fly combat missions. The problem was General Henry “Hap” Arnold, Chief of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), categorically denied the need to use women pilots in any capacity in or with the USAAF. He said he wasn’t sure “whether a slip of a girl could fight the controls of a B-17 bomber in heavy weather.”

In 1942 Congress Instituted the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps

However, there was a move underfoot to introduce women into the military ranks beginning in May 1942 when Congress instituted the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps, later known as Women’s Army Corps (WACS). Gen. George Marshall was fully behind the move, and soon there were the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services (WAVES) and, in smaller numbers, women serving in the Coast Guard and Marine Corps. Photo is Col. Oveta Culp Hobby (right), first director of the WACS.

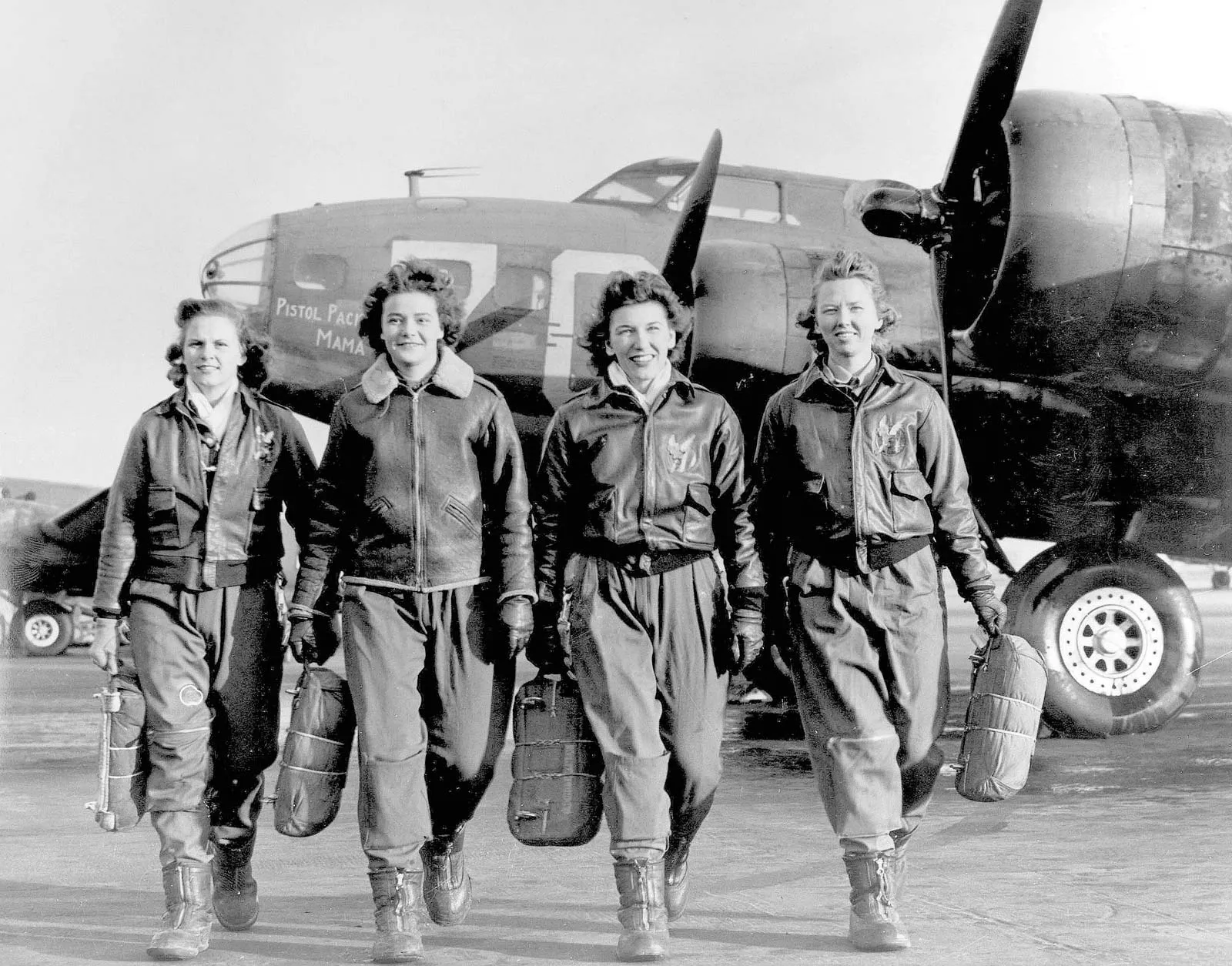

By September 1942, however, the manpower shortages were so acute that Gen. Arnold finally approved the employment of women pilots in the Ferry Division, albeit no longer on a completely equal basis. This proposal provided for the creation of a single experimental woman’s squadron, the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS). Membership in the squadron was restricted to women with a minimum of 500 flying hours and with a 200hp rating.

Altogether 28 women with an average of 1,000 flying hours were sworn into the WAFS.

Cochran Was Appointed the Director of Women Pilot Training

When word reached Jacqueline Cochran – a pioneer in the field of American aviation, considered to be one of the most gifted racing pilots of her generation – about the WAFS, she flew back to Washington and confronted Arnold. Arnold abruptly agreed to establish a “Women’s Flying Training Detachment” (WFTD) and appointed Cochran, the director of women pilot training.

Successive classes of women with 35 hours of previous flying experience went through an average of seven months of training. A total of 1,830 women entered the program, and 1,074 completed training successfully. These women became the first to fly an American military aircraft. Photo is Florene Watson at the controls of her C-47 fighter plane.

General Arnold’s Statement of Women Pilots

They ferried planes from factories to bases, transporting cargo, and participating in simulation strafing and target missions, accumulating more than 60 million miles in flight distances and freeing thousands of male U.S. pilots for active combat duty. More than 1,000 WASP served, and 38 of them lost their lives during the war. In December 1944, General Arnold deactivated the WASP, having flown about 60 million miles in operations. He said publicly at the time, “It is on the record that women can fly as well as men.”

For some reason, all records of the WASP were classified and sealed for 35 years, so their major contributions to the war effort were little known and inaccessible to historians. That was until 1975 when General Hap Arnold’s son, Col. Bruce Arnold, fought Congress to recognize WASP as veterans of World War II. The effort paid off. By 1977, Congress passed, and President Jimmy Carter signed the ‘G.I. Bill Improvement Act of 1977,’ granting the WASP full military status for their service.

On March 10, 2010, at a ceremony in the Capitol, the WASP received the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the highest civilian honors. Nearly 200 of former pilots attended the event, many wearing their World War II-era uniforms.

Today all branches of our military have women pilots flying nearly every aircraft in our inventory. And, in November 2005 to November 2007, the U.S. Air Force had its first female pilot flying with it world-famous “Thunderbirds.” She is Major Nicole Malachowski, who now holds the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

BZ Nicole.

I would like to introduce you to intriguing case of the only lost WASP whose remains were never found. During World War II in 1944, Gertrude “Tommy” Tompkins was flying from California to New Jersey when her plane went missing .Nearly 40 WASPs died in service during World War II, but only one went missing in action (MIA). What happened to Gertrude Tompkins Silver? They were required to provide their own Burials!!!

Gertrude Tompkins was a shy girl with a severe stutter and love for goat farming. She enjoyed the simple life, or at least she did until she fell for a Royal Air Force pilot who infected her with the aviation bug. Not only did she enjoy taking to the skies with him, but she also found the flight lessons he gave her completely intoxicating. He eventually died during a war mission, and while she grieved his loss, she refused to say goodbye to flying. Flying had completely transformed Gertrude, eliminating her stutter and replacing her shyness with bold confidence that surprised all who knew her. She quickly enlisted in a newly launched program with the U.S. Army Air Force, becoming one of 1,074 Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs).

As a WASP, she was trained to fly multiple fighter aircraft, such as the P-38 Lightning, P-47 Thunderbolt and the P-51 Mustang. On a cloudy day in October of 1944, she and 39 others were tasked with ferrying a fleet of Mustangs from California to New Jersey. It took four days for the group to make their destination. That’s when they realized Gertrude was gone. Based on the information available, it was determined that she never made the first stop-over, so she likely went down shortly after departing Mines Field (now LAX). Search efforts lasted for 30 days and covered everywhere from the waters of the Santa Monica Bay to the peaks and valleys of the San Bernardino mountain range. She was never found. Gertrude did not leave behind any children, but she did leave behind a secret new love—a man she had wed only a few months prior. WASP pilots were strongly discouraged from marrying while in service, so she did so quietly and kept her name on file with the military as Gertrude Tompkins. But her real name at the time of her disappearance was Gertrude Tompkins Silver. Prior to take off, Gertrude and two other WASPs encountered cockpit hatch issues. While they were able to resolve Gertrude’s issue on the ground, some wondered if it returned for her after taking off—or that perhaps she encountered another mechanical problem. P-51Ds were notoriously unforgiving, so even the slightest moment of distraction could have turned fatal, and the clouds wouldn’t have done her any favors. WASPs were frowned upon by many of their male counterparts; they were regularly mocked, disrespected, and shunned. Thick skin was an absolute must, but it couldn’t save them from the most disturbing actions taken against them—sabotage. Men were known to stuff items into the women’s engines and fuel tanks, pour acid into their parachute packs, and even slash their tires so they would blow out during or right after takeoff. One WASP made an emergency landing after an engine failure only to discover someone has stuffed rags into it. Another discovered that their flight controls had been intentionally loosened, resulting in some coming off mid-flight.

Perhaps the most famous act of sabotage was the one that killed Betty Davis. Fellow WASP and aviation superstar Jacqueline Cochran found that sugar had been poured into Davis’ gas tank, causing the crash. Is it possible that Gertrude’s disappearance was also an act of sabotage? Sadly, it wouldn’t be the most absurd conclusion. Most believe that Gertrude ran into problems, became disoriented in the clouds, and crashed into the Santa Monica Bay shortly after takeoff. Unfortunately, any real answers can’t be had until both she and the plane are recovered.

As for the WASPs, their fight did not end with the war. It took nearly 30 years before the military acknowledged them as having been active-duty armed service members. Another 35 passed before they were awarded Congressional Gold Medals, which Gertrude’s grandniece accepted on her behalf. Seven decades went by before they were allowed to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Perhaps that is where Gertrude Tompkins Silver can one day be laid to rest, with all the honor she so very much deserves. By the way, I have visited the WWII museum in New Orleans, Louisiana. They are not a part of that Museum!!!